Rosemont was a thriving copper mining settlement in Arizona’s Santa Rita Mountains from 1879 until 1951. You’ll find minimal accessible ruins today, including scattered adobe walls and mining remnants. The area features diverse ecological habitats within Coronado National Forest and holds significant Indigenous sacred sites. Current preservation efforts clash with proposed mining operations, highlighting tensions between cultural heritage and development. The ghost town’s story reveals much about Southern Arizona’s resource-driven settlement patterns.

Key Takeaways

- Rosemont mining settlement operated from 1879-1951, centered around copper extraction before becoming a ghost town after mining ceased.

- The site contains minimal accessible ruins including scattered adobe walls, mining remnants, and foundations of the company store and boarding house.

- Located in the Santa Rita Mountains within Coronado National Forest, approximately 15 miles south of Vail, Arizona.

- Access requires permission as parts of the site are on private property, with no formal tourist facilities present.

- Visitors should exercise extreme caution due to unstable structures, abandoned mining hazards, and wildlife encounters.

The Rise and Fall of Old Rosemont Mining Settlement

As the American West underwent rapid transformation following the Civil War, the Rosemont mining settlement emerged from the rugged terrain of southern Arizona’s Santa Rita Mountains, beginning with the first mining claims filed between 1879 and 1885.

Early prospectors staked the Narragansett claim in 1879 and Eclipse claim in 1884, using primitive mining techniques that would later evolve into industrial-scale operations.

You can trace Rosemont’s prosperity to the copper boom that made Southern Arizona the world’s leading producer by 1907.

The economic impact transformed the region, creating jobs and infrastructure before market fluctuations, labor disputes, and the Great Depression challenged operations.

Today’s proposed Rosemont mine would sit near this historical site within the Coronado National Forest, connecting past extraction efforts to modern mining controversies.

After eight decades of continuous extraction, mining ceased in 1951, abandoning the settlement to ghost town status as workers departed for more viable opportunities.

The area holds significant cultural importance as it contains ancestral burial grounds of the Hohokam people, which has been central to legal challenges against modern mining operations.

Geographical Setting and Natural Environment of the Santa Rita Mountains

The Santa Rita Mountains rise dramatically from the Sonoran Desert floor to form one of southern Arizona’s most distinctive sky island ecosystems, positioned approximately 35-40 miles south of Tucson and extending halfway toward the U.S.-Mexico border.

Exploring the area around the Santa Rita Mountains, visitors can also discover ghost towns in Arizona that offer a glimpse into the state’s rich history and mining heritage. These abandoned communities tell stories of the past, showcasing the rugged beauty and isolation of the desert landscape. Each town presents unique remnants of its former life, inviting adventurers to unravel the mysteries of Arizona’s pioneering days.

These mountains showcase remarkable topographical features, with elevations ranging from 5,000 feet at the base to 9,453 feet at Mount Wrightson’s peak—soaring nearly 6,000 feet above the surrounding desert.

The range’s ecological diversity is evident in its habitat changes, from pine forests at higher elevations to oak-pine communities in mid-elevations and grasslands below. The entire area encompasses 217 square miles of diverse habitats within the Coronado National Forest. You’ll find perennial streams above 6,000 feet supporting riparian zones that attract over 230 bird species, including 15 types of hummingbirds.

Life zones cascade from mountain to valley, creating havens where hummingbirds thrive alongside seasonal waterways.

This Madrean sky island harbors black bears, bobcats, and even jaguars within its rugged terrain of steep slopes and narrow ridges. The area is internationally recognized as a world-renowned birding paradise with incredible diversity of avian species throughout the different elevation zones.

Daily Life and Cultural Heritage in the Historic Mining Community

Within these rugged Santa Rita Mountains, a vibrant mining community once thrived, creating a distinctive cultural landscape shaped by the demands of copper extraction. You’d find a diverse workforce—miners, engineers, and administrators—whose daily lives revolved around the cyclical nature of mining operations between 1870 and 1950.

The social fabric included merchant establishments, healthcare providers, and religious institutions serving as community anchors. During off-hours, residents participated in community gatherings at entertainment venues that fostered cultural traditions within this frontier setting. Modern mining proposals in this region have raised significant environmental concerns about toxic waste potentially affecting Tucson’s groundwater.

Schools educated the miners’ children while agricultural activities supplemented the local economy. Indigenous peoples, particularly the Tohono O’odham, maintained their sacred connection to these lands even as mining activities expanded.

This complex social ecosystem collapsed when copper production ceased in 1951. As employment opportunities vanished, families departed, leaving behind deteriorating infrastructure—physical remnants of a once-flourishing community whose cultural heritage remains embedded in Arizona’s mining history.

Indigenous Sacred Sites and Archaeological Significance

Long before miners carved into the Santa Rita Mountains, this land served as a sacred homeland for the Tohono O’odham Nation and other Indigenous peoples of southern Arizona.

These sacred landscapes contain ancient Hohokam villages, undisturbed burial grounds, and ceremonial sites that date back centuries.

Archaeological preservation efforts have revealed pottery, tools, and settlement structures that document continuous occupation before mining disrupted the area.

The University of Arizona once held human remains that were later repatriated through tribal advocacy.

Today, these sacred sites face existential threats from proposed open-pit mining that would bury cultural heritage under 1.8 billion tons of waste.

The Tohono O’odham and allied tribes continue legal battles to protect these irreplaceable archaeological treasures, demanding proper consultation and recognition of their ancestral rights.

Similar to Calabasas, which was once a Tohono O’odham Village before being abandoned by 1913, Rosemont represents another indigenous territory transformed by external forces.

Like the preserved old schoolhouse in Fairbank, these sites provide educational opportunities for visitors to understand indigenous history before European settlement.

Modern Conflicts Between Preservation and Development

Since the discovery of copper reserves beneath the Santa Rita Mountains, Rosemont has become the epicenter of a contentious battle between development interests and preservation advocates.

You’ll find this struggle embodied in the 9th Circuit Court rulings that blocked mining operations for violating federal protections of tribal cultural resources and environmental standards.

These cultural resource conflicts extend beyond legal battlegrounds. The mining company’s bulldozing of ancestral burial sites without notification illustrates the tension between industrial ambitions and Indigenous sovereignty. The proposed excavation of Gaylor Ranch, a historic Hohokam village, was scheduled to begin within months of construction. Hudbay Minerals Inc. continues to pursue alternative developments like the Copper World project despite ongoing litigation.

While proponents highlight potential jobs and economic sustainability from copper extraction, opponents argue that irreversible damage to sky island habitats and sacred sites represents an unacceptable cost.

The community remains divided between those valuing heritage preservation and others prioritizing regional economic growth through resource extraction.

Visiting Rosemont Today: Remnants and Historical Landmarks

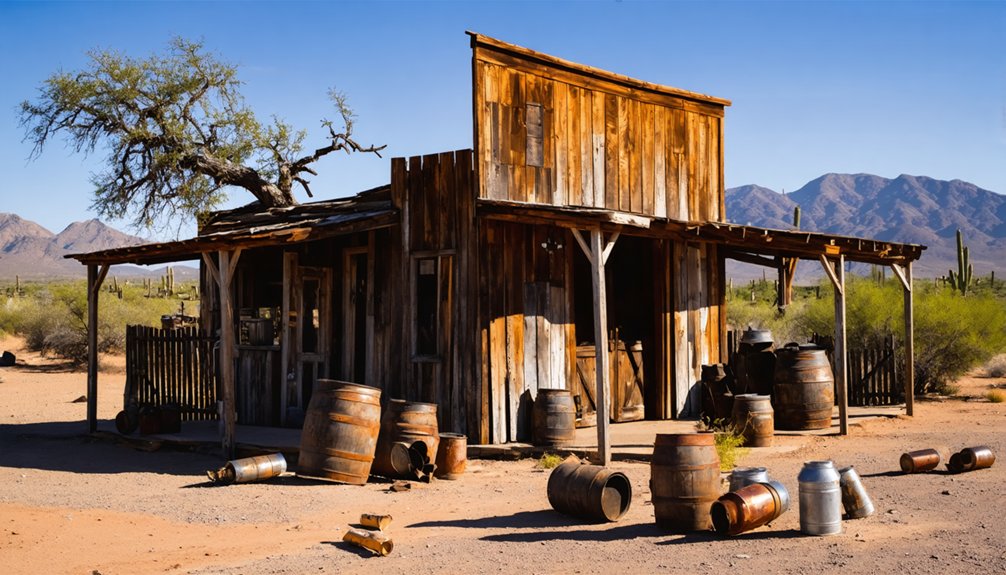

Today’s visitors to Rosemont will find minimal accessible ruins, with only scattered adobe walls and mining remnants marking the ghost town’s former location.

You’ll need to exercise extreme caution when exploring the area due to unstable structures, open mine shafts, and active mining operations that pose significant safety hazards.

Permission should be secured before attempting to visit, as much of the site lies on private property with restricted access and lacks formal historical markers or tourist facilities.

Accessible Ruins

Explorers venturing into the Santa Rita Mountains will find Rosemont’s accessible ruins scattered across public lands managed by the Coronado National Forest.

You’ll discover the remnants of mining architecture through stone foundations of the company store, boarding house, and assay office with its surviving doorways and walls.

The site reveals a town frozen in time, with the mine shaft entrance (now gated for safety) and headframe ruins providing glimpses into Rosemont’s operational past.

Mining artifacts can be spotted throughout the area, from abandoned tools to fragments of the tramway system. The cemetery offers poignant testimony to those who lived and died here.

Access requires traversing a dirt road off Old Spanish Trail, approximately 15 miles south of Vail.

The ruins remain open year-round, though weather conditions may limit accessibility.

Exploration Safety Concerns

While Rosemont’s ruins offer fascinating glimpses into Arizona’s mining past, visitors must navigate significant safety hazards throughout the site. The unstable terrain presents risks of rockfalls and landslides, exacerbated by historic mining activities and natural erosion.

Exploring the history of wilford, arizona ghost town can be equally thrilling yet perilous. As visitors delve into its past, they might encounter remnants of old mining equipment, hinting at the town’s once-thriving community. Those who tread carefully will uncover stories of lost fortunes and the harsh realities faced by the inhabitants of this long-forgotten place.

Exploring white hills ghost town can reveal even more about the mining era that shaped the region. As travelers wander through the abandoned buildings, they may be struck by the silence that envelops the site, broken only by the whispering winds. Each step offers a unique perspective on the challenges faced by those who once called this place home.

Exercise visitor awareness when exploring partially collapsed structures, as falling debris poses serious dangers. Steep, uneven pathways demand appropriate footwear and caution to prevent injuries.

Weather conditions change rapidly in this elevated location, requiring preparation for both intense sun exposure and sudden temperature drops. Respect all posted safety precautions and barriers around mining shafts and tunnels, which remain legally restricted for your protection.

Be mindful of private property boundaries to avoid trespassing. Wildlife encounters, including snakes and scorpions, represent additional hazards when venturing off established paths.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Women Allowed to Work in the Rosemont-Helvetia Mines?

No, women miners were not allowed to work underground at Rosemont-Helvetia mines. You’d find gender equality absent in Arizona’s early mining operations due to legal restrictions and superstitions about women bringing bad luck.

What Diseases Commonly Affected Miners in Early Rosemont?

Like a human hard drive crashing, your body would’ve failed from tuberculosis prevalence, silicosis, chronic bronchitis, lead poisoning, and mercury exposure—all occupational hazards of mining in early Rosemont’s dangerous conditions.

Did Rosemont Have Connections to Arizona’s Statehood Movement?

You’ll find Rosemont’s mining legislation formed economic foundations that bolstered Arizona’s statehood significance. Its copper production provided essential industrial credibility and tax revenue for territorial advancement toward independence.

How Did World War I Impact Mining Operations in Rosemont?

WWI dramatically boosted Rosemont’s copper production for war manufacturing, though you’d find operations challenged by labor shortages. The Narragansett mine yielded 34,300 tons between 1915-1918, representing peak extraction before post-war decline.

What Technologies Revolutionized Copper Extraction in the Rosemont District?

Ever wondered how miners increased yields? You’ll find electrolytic refining and the flotation process revolutionized copper extraction, separating minerals from waste rock with unprecedented efficiency while reducing labor demands.

References

- https://earthjustice.org/article/rosemont-mine-arizona-tribes-tohono-oodham

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helvetia

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-49290.html

- https://washington.office.cnrs.fr/the-rosemont-copper-world-mining-project-a-short-term-game-for-a-long-term-loss/

- https://earthworks.org/releases/rosemont_copper_a_tale_of_two_mines/

- https://data.azgs.arizona.edu/api/v1/collections/AGCR-1552427939083-312/cr-14-d_helvetia-rosemont.pdf

- https://harpers.org/archive/2018/09/copper-mining-in-arizona-silver-bell-mine-morenci-bhp-ascaro-apache-land/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosemont_Copper

- https://www.mtech.edu/mwtp/presentations/docs/kathy-arnold.pdf

- https://www.rosemontminetruth.com