San Miguel City began in 1878 as a mining service center founded by Charles Sharman. The town flourished with the arrival of the Rio Grande Southern Railroad, reaching gold production of $2 million by 1897. After the silver crash of 1893 and World War I, the settlement declined steadily. Today, you’ll find preserved historic structures requiring 4×4 access from May through October. The town’s dramatic boom-and-bust history mirrors many forgotten settlements across the San Miguel Mountains.

Key Takeaways

- San Miguel City, founded in 1878 as a mining service center, reached its peak during the gold rush with $2 million annual production by 1897.

- The ghost town preserves numerous historic structures including boarding houses, mining mills, and tramways listed on the National Register.

- San Miguel miners pioneered technological innovations like the Ames hydroelectric plant and industrial alternating current electricity developed with Tesla.

- Visiting San Miguel requires high-clearance 4×4 vehicles and is best accessed May through October with Telluride as a convenient base.

- The town experienced boom-and-bust cycles with its ultimate decline following the 1893 silver crash and devastating fires in 1929 and 1948.

The Rise and Fall of San Miguel City Mining Camp

As prospectors ventured into the San Miguel River Valley in the late 1860s, they found promising placer gold deposits that would eventually transform the region’s landscape.

Though initially hampered by Ute hostility, the area’s mining heritage truly began in 1878 when Charles Sharman established San Miguel City as a service center for the growing mining community.

You’ll find that San Miguel City thrived alongside nearby camps like Columbia (later Telluride) as silver and gold discoveries attracted diverse settlers to this frontier outpost.

By the 1890s, the arrival of the Rio Grande Southern Railroad fueled unprecedented growth, with annual gold production reaching $2 million by 1897.

Yet this prosperity wouldn’t last—the silver crash of 1893 and later World War I dealt devastating blows, gradually transforming this once-bustling hub into the ghost town you’d recognize today.

By the early 1880s, most residents of San Miguel City had relocated to Telluride where better mining opportunities existed for extracting precious metals from the rich veins of the Upper San Miguel District.

The region’s development was significantly accelerated by Otto Mears’ extensive toll roads which connected previously isolated mining camps to essential supply routes.

Daily Life in San Miguel County’s Lost Mining Communities

While San Miguel City and surrounding communities bustled with mining activity, daily life for residents proved harsh and rudimentary by modern standards. Your daily routines would have revolved around the mining schedule, with most men working difficult shifts using compressed air drills in dangerous conditions. Similar to Ashcroft, which once hosted 2,500 residents and numerous saloons, these mining settlements experienced brief periods of prosperity before eventual decline.

- You’d live in simple wooden cabins without electricity or plumbing.

- You’d rely on wood-burning stoves for heating and cooking.

- You’d fetch water from nearby rivers rather than having piped supplies.

- You’d illuminate your evenings with kerosene lamps or gas lanterns.

- You’d seek entertainment in saloons and dance halls during communal gatherings.

The largely male population faced seasonal challenges, with many families relocating during harsh winters. Much like at Dunton Hot Springs, population fluctuations were common, growing from less than 50 to around 260-300 residents following successful mine operations.

Despite the hardships, these communities maintained social connections through boardinghouse recreation halls and occasional cultural events at opera houses in larger settlements.

Architectural Remains and Historical Structures

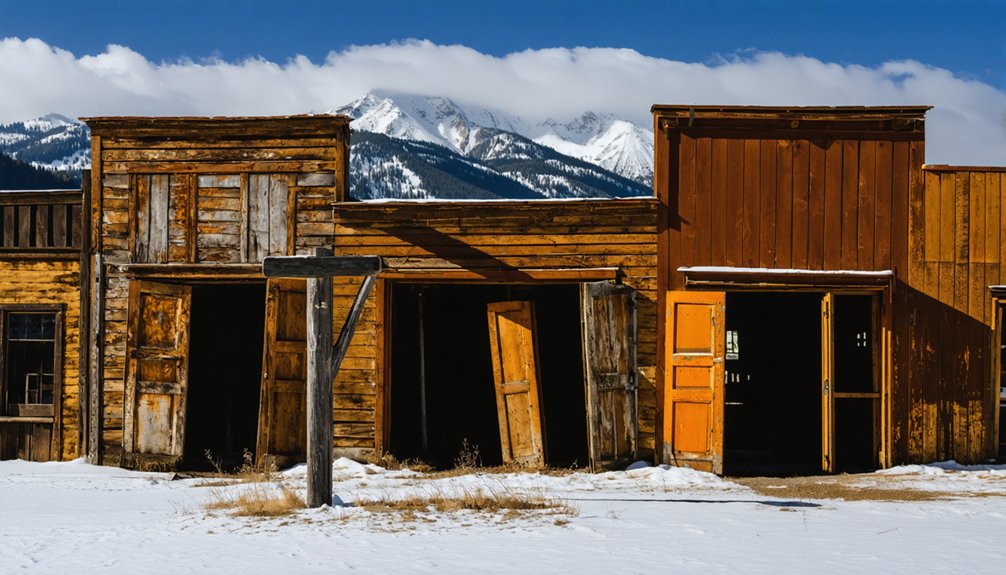

When you explore San Miguel County’s ghost towns today, you’ll discover remarkably preserved structures including boarding houses, mining mills, and tramways that have withstood decades of harsh alpine weather.

The region pioneered architectural innovations like Nikola Tesla’s AC electrical transmission at Alta and aerial tramway systems that revolutionized ore transportation efficiency.

Alta’s historic structures, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, feature salvaged materials from earlier buildings while showcasing the industrial ingenuity that characterized Colorado’s mining heyday. Approximately twenty historic structures remain at the Alta site, accessible via Colorado 145 and Forest Road 632 during summer months when the snow has cleared from the 12,000-foot elevation. Visitors must navigate the rough terrain with high-clearance 4×4 vehicles to reach these historical remnants.

Remaining Structures Today

Nearly a dozen historic buildings still stand in San Miguel, offering visitors a tangible connection to Colorado’s mining past. These remaining structures include residential cabins, a blacksmith shop, and an assayer’s office that highlight daily life during the late 1800s mining boom. The atmosphere here is filled with nostalgia and calm, similar to what visitors experience in St. Elmo.

Preservation efforts by organizations like the National Trust have helped protect these fragile wooden structures from complete deterioration. The town was likely abandoned due to the devaluation of silver in 1893, which caused numerous mining towns across Colorado to close.

- The founder’s home remains intact, showcasing original architectural details

- A historic gas station and diner provide glimpses into everyday town activities

- Original red-cedar water tanks used in mining operations still stand

- Mining equipment and mill remnants dot the landscape near Henson Creek

- Two-story boarding houses represent some of the last extant mining dormitories in Colorado

Architectural Mining Innovations

The San Miguel mining district showcased remarkable architectural innovations that revolutionized Colorado’s mining industry during the late 19th century.

You’ll find evidence of ingenious mining machinery and architectural designs that adapted to the challenging terrain of this isolated box canyon.

The 1890 Ames hydroelectric plant represented a technological breakthrough, powering sophisticated milling operations throughout the district.

Mining camps at Smuggler-Union and Tomboy featured resilient structures housing hundreds of miners in harsh alpine conditions.

The Liberty Bell and Smuggler-Union Mills demonstrated advanced processing capabilities at Pandora, while the Matterhorn Mill‘s long-running operation (1920-1968) showcased evolving industrial architecture.

These facilities incorporated specialized machinery for processing complex silver-rich ores containing galena, sphalerite, pyrite, and tetrahedrite—a remarkable engineering achievement considering the transportation challenges of this remote mountain environment. Before the Rio Grande Southern railroad arrived in 1890, the Valley Floor served as a crucial transportation corridor for delivering mining equipment to San Miguel City.

Mining Operations and Technology Innovations

Mining operations along the San Miguel River began in earnest during the mid-1870s, with placer mining serving as the foundation for what would become a thriving industry in Colorado’s mineral-rich terrain.

By 1875, over 300 men worked claims along the Valley Floor, establishing San Miguel City as a bustling hub of activity.

As mining technology evolved, you’d witness remarkable advancements in mineral extraction that transformed the region:

- Ophir miners pioneered silver ore milling using arrastras in 1879

- The 1883 Ames smelter processed ore locally, eliminating costly shipping

- In 1890, a revolutionary hydroelectric plant at Ames powered the entire operation

- The Idarado Mining Company consolidated claims in the 1930s, introducing large-scale methods

- The Mill Level Tunnel revolutionized both drainage and ore transport efficiency

Natural Surroundings and Geographic Challenges

Nestled in the San Juan Mountains at elevations exceeding 11,500 feet, San Miguel residents battled punishing alpine elements including harsh winters, extreme cold, and heavy snowfall that limited access to just a few summer months.

You’ll find that traversing the steep cliffs and rugged terrain surrounding the town required high-clearance 4×4 vehicles, with narrow mountain passes further restricting transportation options. The area originally earned its name Savage Basin Camp due to these challenging mountain conditions.

The town’s water infrastructure represented remarkable engineering achievements, as settlers harnessed seasonal snowmelt from nearby streams and waterfalls while contending with potential flash flooding during spring runoff.

Punishing Alpine Elements

Perched at breathtaking elevations exceeding 11,500 feet, San Miguel’s ghost towns endured some of North America’s most punishing alpine conditions, which ultimately contributed to their abandonment.

These extreme alpine challenges transformed daily existence into a constant battle against nature’s raw power.

- Oxygen-thin air hampered mining operations and exhausted residents, requiring lengthy acclimatization

- Brutal winters spanning October through May isolated communities for months, causing critical supply shortages

- Avalanche dangers loomed constantly, threatening to sweep entire structures away in seconds

- Freeze-thaw cycles systematically destroyed infrastructure, cracking foundations and pipes

- UV radiation intensity accelerated deterioration of buildings at rates unseen at lower elevations

When you visit these weathered remains today, you’re witnessing structures that withstood decades of nature’s relentless assault—a reflection of the determination of those who briefly called these mountains home.

Valley Access Difficulties

The isolation of San Miguel’s ghost towns extends beyond harsh weather to the very landscape that cradles them.

You’ll encounter formidable valley access challenges when attempting to reach Tomboy at 11,509 feet or Alta at 11,800 feet, both perched precariously on steep mountainsides.

The rugged terrain creates natural barriers that historically limited development and now restricts modern exploration.

Deep canyons cut through the San Miguel Plateau, while avalanche-prone slopes and dense forests obstruct overland travel.

To reach these abandoned settlements, you’ll navigate unpaved roads demanding high-clearance 4×4 vehicles, often closed by seasonal snowfall or rockslides.

The geographic positioning compounds isolation, with settlements separated by miles of wilderness and mountain ranges, ensuring only the most determined visitors experience these remote historical treasures.

Water Engineering Feats

While traversing the challenging terrain of San Miguel, you’ll discover remarkable water engineering feats that transformed this isolated region despite overwhelming geographic obstacles.

The 1968 San Miguel Project attempted to tame these wild waters through infrastructure that balanced competing demands amid the challenging landscape.

- Ames Hydro plant (1891) pioneered industrial AC power transmission, utilizing a 6,500-foot penstock with 700-foot vertical drop.

- The Hanging Flume, an 1880s engineering marvel, clings precariously to canyon walls for placer mining operations.

- Recent restoration efforts returned the river to its natural channel, enhancing ecosystem functionality.

- Water management infrastructure included multiple reservoirs designed to regulate flow for various uses.

- Engineering challenges in this mountainous terrain required innovative solutions like the 700-foot head hydroelectric system.

Notable Characters and Infamous Events

Throughout the history of San Miguel’s ghost towns, several remarkable individuals left their mark on these once-thriving mining communities.

Lucien “L.L.” Nunn’s collaboration with Tesla and Westinghouse at Alta revolutionized mining by implementing the nation’s first industrial use of alternating current electricity. You’ll find the characters’ legacies evident in the engineering achievements that powered the Gold King Mine.

These towns also witnessed notorious incidents that hastened their decline. Alta’s operations ended after devastating fires in 1929 and 1948, with the latter causing a tunnel collapse that trapped three miners who narrowly escaped.

Tomboy, once home to 1,000 residents, experienced tragedy when four miners were executed during a violent dispute in 1919.

San Miguel City’s promising future vanished after severe snowstorms in 1899 forced mass evacuations, marking the beginning of its end.

Visiting San Miguel’s Ghost Towns Today

How can travelers experience the spectral remains of San Miguel County’s once-thriving mining communities today?

These historical sites offer remarkable ghost town exploration opportunities from May through October when mountain roads are most accessible.

- Base yourself in Telluride for convenient access to multiple sites including Alta and Tomboy.

- Bring a high-clearance vehicle—unpaved mountain roads demand it, especially during spring thaws.

- Check access permissions before visiting, as sites span both public and private lands.

- Follow Leave No Trace principles to preserve the historical significance of these fragile ruins.

- Visit Telluride’s information centers for current road conditions and detailed maps.

San Miguel’s ghost towns tell a compelling story of boom-and-bust cycles, with Alta and St. Elmo featuring some of the region’s best-preserved structures, while others showcase nature’s reclamation of human enterprise.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Films or Documentaries Made About San Miguel Ghost Towns?

You’ll find film documentaries like “Ghost Towns of the Rockies” (1940s) and “Legends Of Colorado” series that explore ghost town legends of the region, including potential coverage of San Miguel County’s mining communities.

Did Any Famous Outlaws Frequent These Mining Communities?

Like wolves drawn to vulnerable prey, you’ll find Butch Cassidy prowled these mining communities before robbing Telluride’s bank in 1889. The Wild Bunch and other notorious outlaws thrived in these lawless frontiers.

What Indigenous Tribes Occupied the Area Before Mining Settlements?

You’d find the Ute Tribe dominated this region, establishing seasonal camps along the San Miguel River. They named it “The Valley of Hanging Waterfalls” before mining settlements displaced them. Arapaho Nation also traversed nearby territories.

How Did Mail Delivery Operate in These Remote Mountain Towns?

You’d find Star Route carriers battling treacherous mail routes through avalanches and deep snow, often using snowshoes, toboggans, or hand cars to deliver your correspondence despite life-threatening delivery challenges.

Were There Any Documented Paranormal Experiences in These Ghost Towns?

You’ll find documented paranormal sightings throughout these towns, including Annabelle’s ghost in St. Elmo and ghostly encounters in Animas Forks where a prospector’s spirit reportedly lingers among abandoned structures.

References

- https://www.denver7.com/news/local-news/colorado-ghost-towns-their-past-present-and-future-in-the-rocky-mountains

- https://www.coloradolifemagazine.com/printpage/post/index/id/172

- https://www.historynet.com/ghost-towns-alta-colorado/

- https://kekbfm.com/colorado-ghost-town-alta-2022/

- https://www.valleyfloor.org/mcginley.html

- https://www.clarabush.com/ghost-towns-colorado-alta/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomboy

- https://www.telluride.com/activity/tomboy-ghost-town/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/library/38268/page1/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/early-southwestern-colorado-mining/