You’ll discover Scranton’s abandoned mining settlement in Utah’s rugged landscape, where the New Bullion Mine once employed 90 miners during its 1910-1915 peak. The town flourished briefly with company houses, a dance hall, and general store serving its immigrant workforce. Today, weathered remains tell the story of dangerous underground work, close-knit community life, and the boom-bust cycle that shaped Utah’s early mining towns. The site’s remote setting holds deeper secrets from America’s industrial past.

Key Takeaways

- Scranton was a Utah mining boomtown established after 1869’s transcontinental railroad arrival, centered around the New Bullion Mine’s operations.

- The town’s peak occurred between 1910-1915 with 90 miners working primarily in lead, zinc, and later tungsten extraction.

- Living conditions were basic, with company-owned houses lacking modern amenities, while social life centered around the dance hall.

- Economic decline, limited water resources, and the Hurricane Canal’s construction in 1904 led to the town’s eventual abandonment.

- Located in Five-Mile Pass Recreation Area, the ghost town remains accessible but requires appropriate vehicles and preparation for rugged terrain.

The Mining Origins of Scranton

While Utah’s mining industry took root in the 1860s with Colonel Patrick E. Connor’s California and Nevada Volunteers, the story of Scranton emerged during the state’s significant coal mining era.

You’ll find that Scranton’s geology aligned perfectly with Utah’s rich coal deposits, particularly along the Book Cliffs region where mining flourished after the arrival of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

The Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad’s expansion proved essential for Scranton’s development, as it facilitated the transport of coal to growing markets. The railroad’s discovery of rich coal deposits in the Book Cliffs region spurred rapid development of mining operations.

Like many Utah mining towns, Scranton’s establishment followed the pattern set by earlier mining legislation and corporate development. The town’s workforce included many southern European immigrants, reflecting the broader demographic shifts in Utah’s mining communities.

Mining towns across Utah shared common origins, shaped by established mining laws and business interests of their era.

Like many Utah mining towns, Scranton’s establishment followed the pattern set by earlier mining legislation and corporate development.

As surface deposits depleted elsewhere in the 1880s, coal mining towns like Scranton became increasingly important to Utah’s industrial growth.

Life in an Early 1900s Mining Boomtown

If you’d lived in Scranton during its mining heyday, you’d have spent long days working underground in tomb-like conditions, hauling ore through cramped tunnels while earning wages based on your daily haul’s weight.

Like other workers, you’d have resided in a simple company-owned house, paying rent through automatic paycheck deductions and purchasing necessities at the company store using scrip. The dangerous work environment claimed the lives of many Utah miners, with over 500 miners dying since 1900 due to accidents in the state’s mines. Miners worked tirelessly in three daily shifts, keeping the mine operating seven days a week.

After your shift ended, you could’ve joined fellow miners at the town’s dance hall, where the large wooden floor hosted social gatherings that helped the diverse immigrant community maintain their spirits despite the harsh working conditions.

Daily Work Underground

Deep beneath the Utah soil, miners faced grueling daily work conditions that tested both their physical endurance and courage.

You’d find yourself working long shifts in dark, confined spaces, manually loosening ore with picks and shovels on inclined planes. The mining hazards were constant – toxic gases could spread rapidly through interconnected tunnels, while the threat of explosions loomed overhead.

Without proper protective equipment, you’d battle clouds of dust and debris while hauling 200-pound burlap bags of ore from shafts up to 100 feet deep. Mine superintendent T.J. Parmley led desperate rescue efforts when disasters occurred.

Underground conditions were brutal, with poor ventilation and minimal safety measures. If disaster struck, as it did in Scofield where 200 miners perished, you’d rely on fellow miners to attempt rescue, knowing survival chances diminished by the minute. The diverse workforce included many southern and eastern Europeans who immigrated to Utah seeking mining work.

Housing and Living Conditions

After enduring long, perilous shifts underground, miners returned to living conditions that offered little comfort or respite.

You’d find overcrowded cabins hastily constructed from local wood, with mining families often sharing cramped quarters. Better-off residents might secure homes built from Utah’s red sandstone or limestone, crafted by immigrant stonemasons, but most workers settled for basic shelter. Like the homes in Grafton that were damaged by flooding, many mining town structures were vulnerable to nature’s destructive forces.

You wouldn’t find modern conveniences in these dwellings – no indoor plumbing or electricity. Instead, you’d rely on communal wells for water and outhouses for sanitation.

Wood or coal stoves provided essential heat during harsh winters, while primitive kitchens made food preparation challenging. The constant presence of coal dust and mine debris, combined with poor ventilation and overcrowding, created unhealthy living conditions that plagued Scranton’s residents. Labor agents recruited immigrants for these difficult mining jobs, leading to a diverse mix of European and Asian workers sharing these challenging living conditions.

Social Life After Dark

Life after sunset in Scranton revolved around the town’s boarding houses and saloons, where exhausted miners sought refuge from their grueling shifts.

You’d find nighttime camaraderie through card games, storytelling, and occasional music in these male-dominated spaces, with dim lantern light casting shadows on wooden walls.

The town’s transient gatherings reflected its workforce – mostly single men who’d drift between mining camps.

While the general store served as a daytime hub, evening activities centered on informal get-togethers in boarding houses.

During the World War I tungsten boom, you might’ve noticed increased nighttime activity around ore shipments.

But without permanent entertainment venues or family-oriented spaces, social life remained simple and unstructured, much like the nearby town of Eureka with its Porter Rockwell cabin and historic buildings.

The town’s wooden buildings and limited lighting meant you’d need to exercise caution after dark.

Unlike its Pennsylvania namesake with its extensive rail network, this mining settlement had minimal infrastructure for moving people and goods.

The New Bullion Mine’s Role

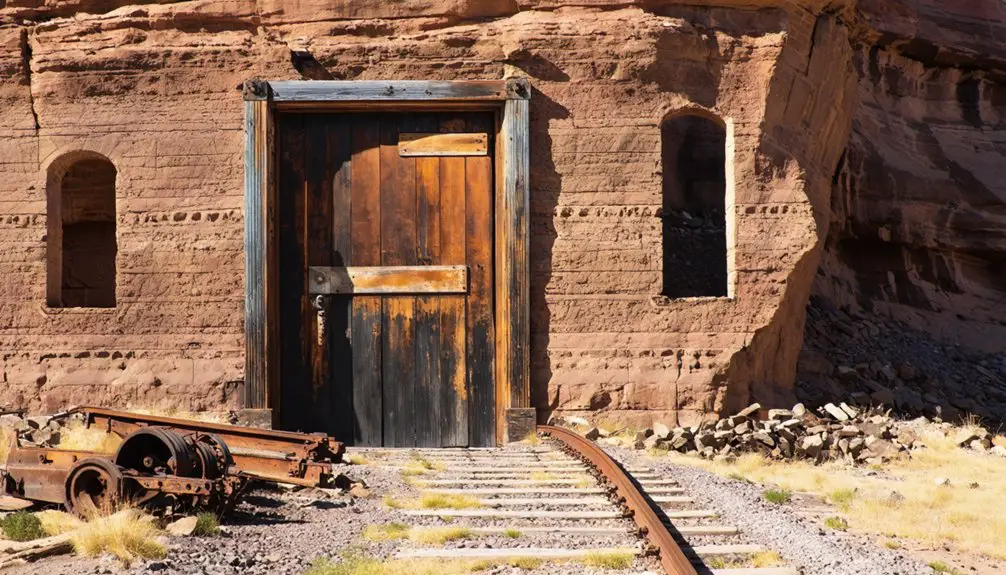

The New Bullion Mine served as the economic backbone of Scranton, Utah, following its establishment in 1908 by the Scranton Mining and Smelting Company.

You’ll find this operation was initially focused on lead and zinc extraction, employing mining technology typical of early 20th-century operations in the North Tintic Mining District.

During World War I, you’d have seen the mine adapt to wartime demands, shifting to valuable tungsten production that was so precious it required insured parcel post shipping.

The mine experienced the harsh reality of economic cycles when post-war mineral demand plummeted. While the South Scranton company attempted to extend operations in 1914 through additional tunneling, the mine’s limited ore reserves couldn’t sustain long-term prosperity, ultimately leading to the town’s decline.

Peak Years and Economic Prosperity

During Scranton’s peak years, you’d find a bustling mining community where silver extraction operations attracted hundreds of workers and their families, creating a typical late 19th-century Utah boomtown atmosphere.

You could see the town’s prosperity reflected in its expanding infrastructure, which included stamp mills, general stores, saloons, and modest civic buildings constructed from hauled lumber and local adobe.

The economic success drew merchants and tradespeople to support the mining operations, though wealth remained concentrated among mine owners while laborers earned standard mining wages of the era.

Mining Operations and Profits

Mining activity in Scranton reached its zenith between 1910-1915, when roughly 90 miners worked the New Bullion Mine‘s rich deposits of lead and zinc. The initial ore pocket delivered substantial mining profits, though they’d prove short-lived once the easily accessible deposits were exhausted.

During World War I, you’d have seen operations shift dramatically to tungsten extraction, which brought a temporary economic revival to the area.

- The mine’s valuable tungsten ore was so precious it required shipment by insured parcel post

- The South Scranton company expanded operations in 1914 by digging an extensive tunnel

- The town supported a complete mining infrastructure including an assay office for testing ore quality

These operations sustained Scranton’s economy until the post-war period, when declining ore yields forced most miners to seek opportunities elsewhere.

Population Growth and Development

Founded in 1908, Scranton grew rapidly around the New Bullion Mine, attracting nearly 90 miners and their families to this modest Utah settlement.

Population demographics reflected the town’s singular focus on mining, with residents centered around the New Bullion Mine’s operations. You’d have found essential amenities including miners’ homes, a boarding house, and a general store that doubled as the post office.

Economic fluctuations closely followed the mine’s fortunes, particularly during World War I when tungsten production briefly boosted the town’s prospects.

While smaller than booming cities like Frisco with its 6,000 residents, Scranton maintained steady growth until ore depletion began affecting the community.

The town’s peak years lasted from its founding through the war years, before declining sharply as mining operations ceased.

Community Life During Prosperity

Life in prosperous Scranton revolved around the New Bullion Mine, where you’d find roughly 90 miners and their families creating a close-knit community built on shared labor and daily routines.

The town’s heartbeat centered on the general store and post office, where community gatherings naturally formed as miners collected mail and supplies.

Your daily life in Scranton would’ve included:

- Working alongside fellow miners extracting lead, zinc, and precious metals

- Living in either your own home near the mines or sharing space in the communal boarding house

- Participating in the town’s economic pulse through the assay office, where you’d test ore samples

While cultural amenities were limited, you’d find strong social bonds forged through shared labor conditions and reliance on common facilities, creating a resilient mining community despite its transient nature.

Decline and Abandonment

Despite initial hopes for agricultural prosperity, Scranton’s decline began as the limited irrigable land and frequent Virgin River flooding created insurmountable challenges for farmers.

The settlement patterns shifted dramatically as younger generations left to seek opportunities elsewhere, unable to expand their farmland due to irrigation constraints.

You’ll find that economic decline accelerated when the Hurricane Canal’s construction in 1904 drew settlers away to areas with better water resources.

Families relocated gradually, some even moving their entire houses to nearby towns.

The lack of modern amenities like electricity and culinary water, combined with persistent environmental challenges, sealed Scranton’s fate.

What Remains Today

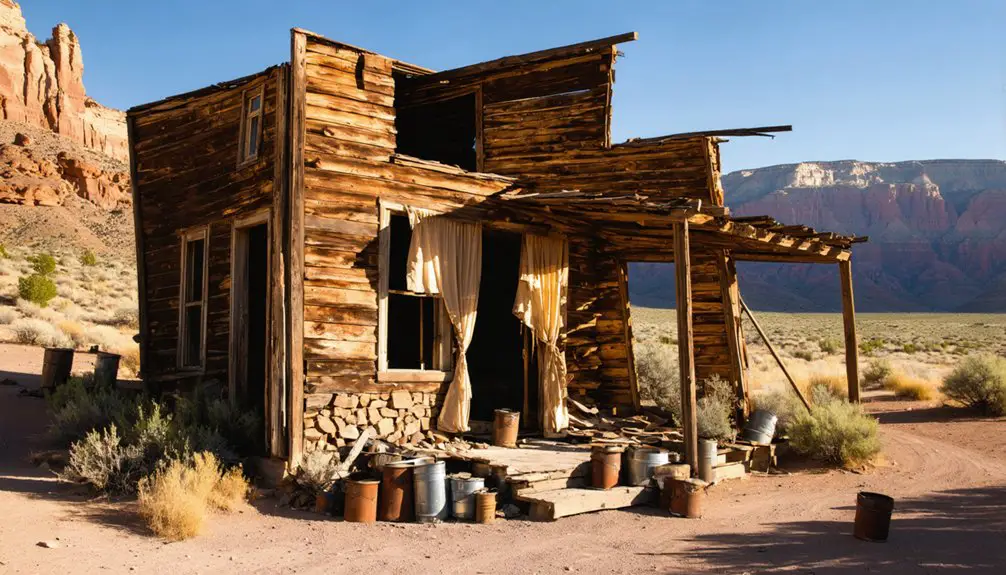

When exploring Scranton’s remains today, you’ll find scattered ruins telling the story of its once-bustling community.

Scattered among desert winds, Scranton’s weathered ruins whisper tales of a vibrant mining town long since passed.

The desert landscape has reclaimed much of the townsite, with sagebrush and natural erosion reshaping the terrain around historic remnants. You can access the ghost town via dirt roads commonly used for off-road adventures, though you’ll need to come prepared with water and navigation tools.

Key visitor experiences include:

- Examining crumbling adobe walls and wooden sidewalk fragments that hint at the town’s former layout

- Discovering old mining equipment and stone kiln remains scattered throughout the area

- Encountering reported paranormal activity near building ruins and cemetery sites

The site now serves as an open-air museum of Utah’s mining heritage, protected for exploration while naturally weathering with time.

Historical Significance in Utah Mining

Established in 1908, Scranton emerged as a significant player in Utah’s North Tintic Mining District through its rich deposits of lead and zinc at the New Bullion Mine.

The town’s mining technology centered on extracting strategic metals, particularly tungsten during World War I, which you’ll find was carefully shipped by insured parcel post due to its wartime value.

The town’s community dynamics reflected the era’s company-owned structure, where you’d see about 90 miners and their families supported by essential services like the general store and assay office.

While the initial ore pocket lasted only two years, Scranton’s impact on Utah’s mining history showcases the region’s boom-and-bust cycle and its role in America’s wartime industrial effort, particularly through its specialized mineral production in the North Tintic District.

Preservation Efforts and Current Status

Unlike many preserved Utah ghost towns, Scranton faces significant preservation challenges with minimal remaining infrastructure and no formal protection status.

You’ll find the site largely reclaimed by nature, with most original structures deteriorated beyond recognition. Local advocacy remains minimal, with no dedicated community groups or volunteer organizations coordinating preservation efforts.

Here’s what characterizes Scranton’s current preservation status:

- Absence from Preservation Utah’s 2025 Most Endangered list indicates no prioritized statewide protection

- Natural decay and erosion continue unchecked without stabilization work

- Limited scholarly research or media coverage exists about the site’s conservation needs

The town’s future preservation depends primarily on increased local awareness and potential partnerships with regional historical societies or academic institutions, rather than established state or federal programs.

Visiting the Ghost Town Site

Modern adventurers seeking to explore Scranton’s remnants will find the ghost town nestled in Utah’s Five-Mile Pass Recreation Area, approximately 30 miles west of Lehi.

Journey to Scranton ghost town, hidden within Utah’s Five-Mile Pass Recreation Area, where adventure awaits just 30 miles from Lehi.

You’ll need to navigate State Route 73 through Five Mile Pass, where the site lies within BLM-managed public lands.

For successful adventure planning, bring all necessary supplies – there aren’t any services on-site. The area’s rugged terrain supports various activities, from ghost hunting to OHV riding, but you’ll want a capable vehicle to traverse the challenging landscape.

Weather conditions can change rapidly, so check forecasts before visiting. The site’s popularity has grown considerably, with annual visitors doubling to 120,000 in 2020.

While fewer structures remain compared to other Utah ghost towns, the remote setting offers an authentic exploration experience.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Average Salary of Miners Working in Scranton?

Off the beaten path, you’d earn between $2-$4 daily in mining wages during the early 1900s, totaling $60-$120 monthly, with labor conditions and wartime tungsten demand affecting your actual pay.

Were There Any Major Accidents or Disasters at the New Bullion Mine?

You won’t find documented major accidents or disasters in mine safety records specifically at the New Bullion Mine. While accident reports exist for other Utah mines, none show catastrophic events here.

Did Any Famous People Ever Visit or Live in Scranton?

You won’t find any records of famous visitors or celebrity sightings in this small mining town. Its population consisted solely of miners and their families during its brief existence from 1908 until after WWI.

What Happened to the Mining Equipment When the Town Was Abandoned?

You’ll find most abandoned machinery was left to rust in place, with only smaller tools taken away. The remaining mining relics deteriorated over decades, some surviving until fires in 1971.

Were There Any Schools or Churches Established During Scranton’s Peak Years?

While 80% of Utah mining towns had education facilities and religious institutions, you won’t find concrete evidence of schools or churches in Scranton’s peak years – though informal gatherings likely occurred.

References

- https://www.deseret.com/utah/2024/06/03/how-to-visit-utah-ghost-towns/

- https://lifeinutopia.com/utah-ghost-towns

- https://www.utahlifemag.com/printpage/post/index/id/249

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Utah_Ghost_Towns

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Scranton

- https://historytogo.utah.gov/mining/

- https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/c/COAL_MINING_IN_UTAH.shtml

- https://utahrails.net/mining/brewster.php

- https://utahstories.com/2017/07/revisiting-utahs-mining-past/

- https://wchsutah.org/documents/whitley-mining-book.pdf