You’ll find Scull Shoals in Greene County, Georgia, where a once-bustling mill town now stands in ruins. Established in 1782, it evolved from Native American hunting grounds into a fortified settlement, then grew into a major industrial center with textile mills employing 600 workers. The devastating flood of 1887 submerged the mills for four days, leading to the town’s abandonment by 1900. Today, brick walls, foundations, and two ancient Indian mounds hint at centuries of untold stories.

Key Takeaways

- Scull Shoals was a thriving industrial mill town established in 1782 near the Oconee River that later became abandoned.

- The town’s decline began after devastating floods in 1887 destroyed the mills and ruined hundreds of cotton bales.

- By 1900, most residents had fled the area, leaving behind ruins of brick warehouses, stores, and an arched bridge.

- The ghost town’s remains are now preserved within the Oconee National Forest, featuring hiking trails and historic structures.

- Local folklore includes ghost stories of former residents, unexplained footsteps, and apparitions linked to the 1887 flood tragedy.

The Birth of a Frontier Settlement

As European settlement pushed into the Georgia frontier, Scull Shoals emerged in 1782 near the Oconee River in Greene County, taking its name from Native American skeletal remains exposed at nearby indigenous mounds.

You’ll find this wasn’t just any frontier location – it was a strategic spot where Native Americans, including the Creek Nation and earlier Mississippian cultures, had hunted and gathered for centuries.

Settlement challenges were immediate and complex. While the fertile river shoals offered prime conditions for establishing gristmills and sawmills, indigenous interactions were often tense. Archaeological excavations in the 1990s revealed fort remains beneath centuries of soil.

Early settlers faced dual realities: prime mill locations along the shoals, yet uneasy relations with indigenous peoples.

The area marked a contested boundary between colonial lands and Creek territory, leading to raids and conflicts. By 1793, settlers had erected Fort Clark, a two-story blockhouse with stockade walls, reflecting the precarious nature of frontier life. A local militia unit called Phinizey’s Dragoons was tasked with manning the defensive fortification.

From Native Land to Colonial Defense

While indigenous peoples had thrived at Scull Shoals for centuries before European contact, the area’s cultural landscape changed dramatically after Hernando de Soto’s 1540 expedition devastated the Ocute chiefdom.

You’ll find evidence of these cultural shifts in the area’s two large Indian mounds, where the Mississippian peoples practiced corn agriculture from 900 A.D. until European diseases forced their abandonment.

During their occupation, pottery sherds and stone tools were left behind as evidence of their extensive presence.

Historical conflicts intensified as settlers moved in during the late 18th century.

After Creek raiders killed six settlers in April 1793, you’ll discover how the community responded by building Fort Clark, a two-story blockhouse manned by Phinizey’s Dragoons.

The settlement experienced rapid growth with the establishment of the state’s first paper mill in 1811.

The Treaties of 1802 and 1805 ultimately pushed the Creek Nation westward, transforming Scull Shoals from contested frontier to agricultural center.

The Rise of Industrial Power

You’ll find Scull Shoals’ transformation into an industrial powerhouse began with Thomas Ligon’s 1807 cotton ginnery, followed by Zachariah Sims’ pioneering paper mill in 1811.

The village’s economic might grew exponentially under Dr. Thomas Poullain, who by 1832 had established the Skull Shoals Manufacturing Company with $45,000 in capital.

The mill complex reached its peak production with four thousand spindles operating at full capacity, employing hundreds of workers in the region.

The community thrived until the 1887 flood devastated the infrastructure and led to its eventual abandonment.

Mills Shape Local Economy

In 1811, Georgia’s industrial landscape changed forever when Scull Shoals became home to the state’s first paper mill, powered by the natural shoals of the Oconee River.

Though this initial venture lasted only four years before bankruptcy, it set the stage for a thriving mill economy under Dr. Thomas Poullain’s leadership from 1827 onward.

You’d have witnessed a remarkable transformation as Poullain expanded operations, building multi-story brick mills and creating a self-contained company town complete with stores, boarding houses, and a toll bridge.

The labor dynamics grew increasingly complex, with over 600 workers, including families and children, producing Osnaburg fabric.

Today, visitors can explore the peaceful, secluded environment while imagining the bustling industrial past of this historic site.

The site’s early Native American presence had laid the groundwork for centuries of continuous human activity along these productive riverbanks.

Cotton Empire Expands

After Eli Whitney’s cotton gin revolutionized production in 1793, Scull Shoals rapidly transformed from a modest milling settlement into a cotton empire.

You’d have witnessed an unprecedented economic transformation as cotton cultivation exploded, with local farmers harvesting 12,000 bales annually by 1830.

According to The Georgia Historical Quarterly, the local textile industry became a significant economic driver in Greene County’s development during the antebellum period.

The real power shift came in 1827 when Dr. Thomas Poullain acquired 1,620 acres and the mills, becoming Greene County’s largest slaveholder.

By 1832, the newly incorporated Skull Shoals Manufacturing Company commanded $45,000 in capital from five investors.

The Poullain and Wray families soon controlled every aspect of cotton production, from planting to distribution.

Their industrial dominance peaked in 1854, when the mill complex employed over 600 workers, operated 2,000 spindles, and processed 4,000 bales of cotton worth $200,000 annually.

Life in the Mill Village

Life at Scull Shoals centered around the bustling textile mill, where over 600 workers operated 2,000 spindles and looms by 1854.

The mill hummed day and night as hundreds of workers tended to thousands of spindles, transforming raw cotton into valuable textiles.

You’d find mill workers living in company-provided “saddlebag” houses, designed to accommodate large families with five or more members. The mill owners sought families specifically, as children were expected to contribute to production alongside their parents.

Dr. Poullain’s leadership transformed the village into a self-contained community. You’d have access to stores, boarding houses, and a distillery, while a toll bridge connected you to broader trade networks. The village eventually declined after devastating floods in the 1880s destroyed many of the mills.

The workforce was diverse, including free laborers and enslaved people, with Dr. Poullain owning 145 enslaved workers who primarily cultivated cotton for the mill’s massive 4,000-bale annual consumption.

Notable Characters Who Shaped Scull Shoals

While the mill village hummed with daily activity, several remarkable individuals left their mark on Scull Shoals’ development.

You’ll find Dr. Lindsey Durham‘s legacy in herbal remedies, blending Native American and European healing traditions at her 600-bed hospital.

Dr. Thomas N. Poullain transformed the area after purchasing the mills in 1827, expanding operations while maintaining 145 enslaved workers.

Zachariah Sims and George Paschal pioneered Georgia’s first paper mill in 1811, setting the foundation for industrial growth.

Governor Peter Early’s presence briefly brought state attention to the town.

Perhaps most surprisingly, you’ll discover Reverend Adam D. Williams‘ connection to civil rights history – born here as a laborer, he later became pastor of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church and grandfather to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Great Floods and Economic Downfall

The devastating flood of 1887 marked the beginning of Scull Shoals’ downfall, as raging waters submerged the mills for four straight days. The flood’s impacts were catastrophic – destroying the covered toll bridge, ruining hundreds of cotton bales, and devastating 600 bushels of stored wheat.

You’ll find it’s no surprise the community’s economic resilience crumbled under such pressure.

A century of cotton farming had already weakened the area’s environmental defenses, stripping 8-9 inches of topsoil that washed into the Oconee River. By 1860, the original rapids lay buried under silt, and by the 1920s, they’d disappeared under 14 feet of sediment.

The community couldn’t recover from these repeated blows. By 1900, most residents had fled, the mills closed permanently, and Scull Shoals faded into a ghost town.

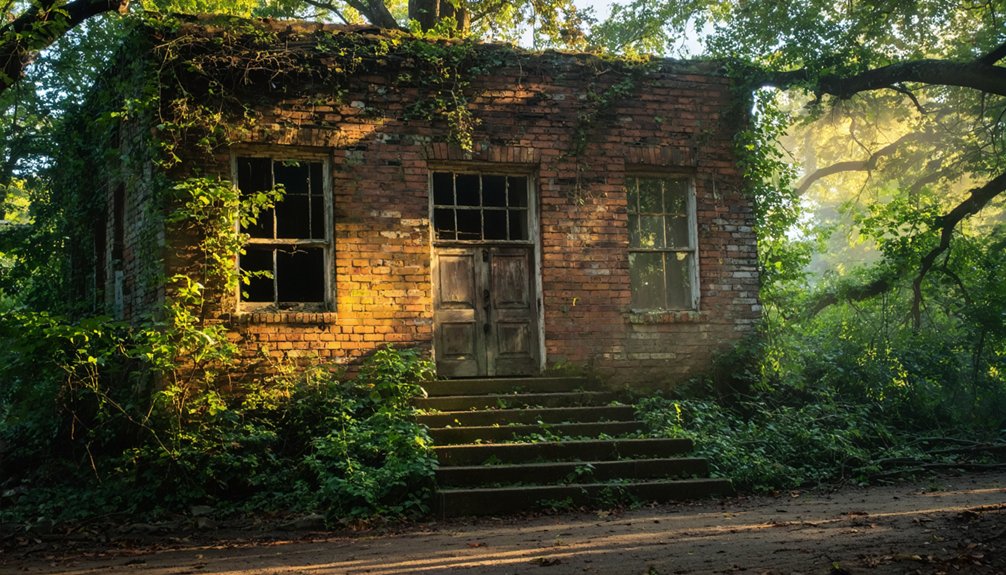

What Remains: Exploring the Ruins Today

Modern visitors to Scull Shoals can explore several surviving structures from its industrial heyday, including three brick walls of the original warehouse and store, an arched brick bridge that once carried mill workers, and scattered stone foundations from the power plant.

This historical exploration of the ghost town reveals traces of its past glory, with remnants carefully preserved within the Oconee National Forest.

- Brick and stone chimney bases dot the village landscape and surrounding woodlands

- Remnants of the wooden covered toll bridge still emerge from the Oconee River

- The site’s gentle hiking trails wind through the ruins, connecting various historical structures

- Picnic areas offer strategic viewpoints to appreciate the architectural remains

You’ll find the site accessible via a dirt road from Greensboro, with daily visiting hours from 8:00 AM to 6:00 PM.

Archaeological Discoveries and Heritage

When you explore Scull Shoals’ archaeological record, you’ll find evidence of Native American settlements dating back 10,000 years, including two significant mounds from the Mississippian period around 900 A.D.

The site’s industrial heritage is documented through the remains of Georgia’s first paper mill from 1811, alongside ruins of grist mills and warehouses that operated throughout the 19th century.

Today, ongoing preservation efforts, led by archaeologists like Dr. Jack Wynn, combine modern technologies such as GPR and LIDAR with traditional excavation methods to protect and study the site’s artifacts, from ancient pottery sherds to industrial-era machinery.

Native American Settlement Evidence

Archaeological evidence reveals that Native American hunter-gatherers first settled at Scull Shoals roughly 10,000 years ago, drawn to its fertile shoals for hunting and settlement.

You’ll find that this rich cultural heritage spans from these early inhabitants through the Mississippian Period, which began around 900 A.D. and brought corn agriculture to the Oconee Valley. The site’s significance is particularly evident in its impressive mounds and Native American artifacts.

- Mound A stands 11 meters high, while Mound B reaches 3 meters, both testifying to sophisticated cultural practices

- UGA’s 1983 field school excavations reached depths of 3.5 meters, mapping the site’s extensive history

- The area shows continuous occupation from Late Etowah through Savannah and Lamar Periods

- The Creek Nation frequently used the land as a hunting reserve, sometimes engaging in territorial conflicts

Industrial Era Structural Remains

As Native American settlements gave way to European development, Scull Shoals entered its industrial era with the establishment of Georgia’s first paper mill in 1811.

The mill’s structural preservation reveals a pattern of industrial architecture that expanded under Dr. Thomas Poullain’s leadership in 1827, including gristmills, sawmills, and a distillery.

You’ll find remnants of these once-thriving enterprises at the site today, with the foundations of the water-powered mills still visible.

The industrial complex grew considerably until the devastating floods of the 1880s, particularly the 1887 flood that destroyed the covered toll bridge and damaged essential infrastructure.

While nature ultimately reclaimed much of Scull Shoals, the remaining structural foundations serve as silent witnesses to the town’s industrial ambitions and eventual decline.

Preserving Historical Artifacts Today

Extensive archaeological excavations at Scull Shoals began in 1983 when the University of Georgia targeted the site’s ancient mounds and village areas.

Today, strict artifact preservation policies guarantee the site’s historical integrity remains intact for future generations. You’ll find ongoing research supported by community volunteers and universities, with modern technologies like GPR and LIDAR drone imaging providing non-invasive ways to study buried features.

- The U.S. Forest Service manages the site as part of Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest, protecting it since 1959

- Friends of Scull Shoals (FOSS) partners with officials to maintain trails and conduct educational programs

- Archaeological visibility faces challenges from thick vegetation and alluvial soil deposits

- Removal of artifacts is prohibited to preserve the site’s research potential and educational value

Tales and Legends of the Abandoned Town

While the physical ruins of Scull Shoals tell their own story, the ghostly legends surrounding this abandoned town paint an equally compelling narrative.

As you explore the crumbling remnants, you’ll discover why locals speak of haunted whispers echoing through deserted streets and ghostly sightings of former residents wandering the grounds.

You can hear unexplained footsteps and slamming doors throughout the ruins, while apparitions of those who once called this place home reportedly materialize among the overgrown paths.

Many believe these are the restless spirits of townspeople who endured devastating floods and fires, particularly the catastrophic 1887 flood that marked the beginning of the end for Scull Shoals.

Their tragic stories continue to captivate visitors, making this ghost town a focal point of regional folklore.

ghostly tales from Lake Lanier often weave narratives of lost loves and unanswered mysteries that echo through the waters. Locals share chilling accounts of spectral figures wandering the shore, each story adding to the lake’s eerie reputation. With each retelling, the allure of Lake Lanier grows, drawing thrill-seekers and those curious about the supernatural to uncover its secrets.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Camping Allowed Near the Scull Shoals Ruins?

Home is where you pitch your tent! You’ll find campgrounds nearby at Scull Shoals Park, but you can’t camp directly at the ruins. Follow camping regulations for the national forest area.

What Is the Best Season to Visit Scull Shoals?

You’ll find the best weather in autumn, when crisp temperatures and falling leaves create perfect conditions for exploring. Trails are drier, insects are fewer, and you’ll enjoy clearer views of ruins.

Are Guided Tours Available at the Historic Site?

Like footprints in shifting sand, guided experiences at this site have faded away. You’ll need to explore the historical significance on your own through self-guided walks among the ruins.

How Much Time Should Visitors Plan for Exploring the Area?

You’ll need 1-2 hours for basic exploration tips: 30 minutes for main ruins, an hour for riverbank trails. For in-depth visitor experiences, plan 3-4 hours including picnics and extended hiking.

Is Special Permission Required to Conduct Photography or Research?

You’ll need Forest Service permits for research that disturbs the site, but casual photography’s allowed without special permission. Check with the local USDA office about current photography permissions and research guidelines.

References

- https://visitlakeoconee.com/business/scull-shoals/

- https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/trip-ideas/georgia/ghost-town-day-trip-ga

- https://wander-woman.blog/2016/07/01/scull-shoals-a-ghost-town/

- https://www.visittownscounty.com/whispers-of-the-past-ghostly-tales-from-towns-county-georgia/

- https://vanishinggeorgia.com/2015/11/18/scull-shoals-greene-county-2/

- https://www.scullshoals.net/history

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scull_Shoals

- https://exploregeorgia.org/greensboro/general/historic-sites-trails-tours/historic-scull-shoals-mill-village

- https://www.hairofthedawg.net/thread-311.html

- https://packgoats.wordpress.com/2022/05/15/falling-creek-trail-at-scull-shoals-historic-site-in-chattahoochee-oconee-national-forest/