You’ll find Sego’s stone ruins nestled in Utah’s Book Cliffs, where high-grade anthracite coal discovery sparked a bustling mining town in the 1890s. At its peak, 500 residents and 125 miners produced 1,500 tons of coal daily, supported by the Ballard & Thompson Railroad. The town’s diverse immigrant community faced harsh working conditions until declining coal demand forced its abandonment in 1955. Today, weathered buildings and ancient petroglyphs offer glimpses into Sego’s complex past.

Key Takeaways

- Sego was a thriving coal mining town in Utah that peaked with 500 residents, producing up to 1,500 tons of coal daily.

- The town was established in the 1890s after Harry Ballard discovered high-grade anthracite coal and later became American Fuel Company’s operation.

- Diverse immigrant workers from Europe, Asia, and African Americans formed the mining community, facing harsh working conditions and cultural challenges.

- Railroad infrastructure, including 13 trestle crossings, connected Sego to Thompson Springs and was crucial for coal transportation.

- Today, Sego is a ghost town with preserved stone walls of the company store, protected petroglyphs, and managed by BLM.

The Discovery of Coal and Town Origins

While many ghost towns in Utah emerged from silver and gold rushes, Sego’s story began with Harry Ballard’s discovery of high-grade anthracite coal in the early 1890s.

Unlike Utah’s precious metal boomtowns, Sego rose from Harry Ballard’s discovery of valuable anthracite coal deposits in the 1890s.

As a successful sheep and cattle rancher, Ballard recognized the value of his find and strategically kept it quiet while acquiring surrounding coal-rich lands.

You’ll find the earliest signs of mine ownership changes in 1911 when B.F. Bauer, a hardware store owner, purchased Ballard’s property for $1 million and established the American Fuel Company.

The town’s name evolved from Ballard to Neslin, and finally to Sego, after Utah’s state flower.

The coal quality attracted significant investment, leading to rapid development including a coal washer, mining buildings, and a boarding house to support the growing operations. By 1928, the mine was producing an impressive 1,500 tons daily with its skilled workforce.

At its peak, the town supported 125 working miners and reached a population of approximately 500 residents.

Life in a Mining Boomtown

If you’d ventured into Sego during its peak years, you’d have found a bustling community of 500 residents where English, Scandinavian, Italian, Greek, African American, and Japanese miners worked side by side in the coal mines.

The daily rhythm of life centered around the mines, where 125 workers faced constant underground hazards including fires and equipment failures while extracting up to 1,500 tons of coal per day. American Fuel Company took control of operations in the early days, investing heavily in the mines’ development. The transition to diesel-fueled locomotives in the railroad industry ultimately spelled doom for Sego’s coal mining operations.

The town’s social fabric was woven around essential structures like the company store, boarding house, and schoolhouse, creating a close-knit mining community that persisted until declining coal demand forced families to seek opportunities elsewhere.

Daily Mining Town Routines

As Sego’s coal mine reached its peak production of 1,500 tons daily by 1928, the town’s 125-150 miners settled into demanding routines shaped by the rhythms of industrial coal extraction.

You’d find workers trudging to their shifts, armed with basic tools before mechanization improved conditions. Between grueling underground work, you’d spot them at the two-story clubhouse for community gatherings or heading to the company store with scrip in hand. Japanese miners worked diligently in the northern section of town, maintaining their own distinct community area.

Life followed strict ethnic divisions in housing zones, but everyone’s schedule revolved around the mine’s demands. The town’s abandoned brick building still stands as a lonely reminder of its once-bustling past.

After unionization in 1933, you’d see more organized miner schedules and regular wages. The Ballard & Thompson Railroad’s daily rhythm of coal shipments and supply deliveries kept the town’s pulse beating, though water shortages and safety hazards remained constant challenges.

Immigrant Worker Community Life

The immigrant workers of Sego shaped the town’s social fabric through distinct cultural enclaves and complex community dynamics. You’d find Greeks and other European groups maintaining their cultural traditions while maneuvering the harsh realities of mining life. Social events often brought miners together through baseball games and community dances.

Despite ethnic tensions and racial discrimination, immigrant solidarity emerged through shared gathering spaces like bakeries and pool halls.

Life wasn’t easy in the company-controlled environment. You couldn’t escape the economic grip of company scrip or the cramped boarding houses where workers shared rooms to survive. The American Fuel Company controlled mining operations, employing around 125 miners during peak production years.

Yet immigrant communities built resilient support networks, organizing secretly through unions despite threats of dismissal or eviction. When labor disputes erupted, these tight-knit groups faced violence and displacement together, showcasing both the strength and vulnerability of Sego’s immigrant population.

Underground Dangers and Challenges

Mining beneath Sego’s dusty surface presented deadly hazards that workers faced during every shift underground.

You’d find primitive mine safety conditions where coal dust accumulations could trigger massive chain-reaction explosions throughout connected tunnels. When ventilation fans failed, deadly gases like carbon monoxide would spread rapidly through the shafts, leaving you with few escape options. Tragic incidents like the Winter Quarters disaster showed how stopped pocket watches provided the only evidence of when miners met their fate. The bituminous coal seams presented especially volatile conditions that led to numerous deadly explosions throughout Utah’s mining history.

The mine’s structural integrity constantly threatened your survival, with timber supports prone to collapse and geological instabilities causing sudden roof falls.

Air quality posed another silent killer – stale air pockets and toxic gas buildups could suffocate you without warning. You’d work long hours in dark, confined spaces while battling both physical exhaustion and the psychological strain of knowing that primitive emergency response systems mightn’t reach you in time during a disaster.

Railroad Development and Transportation

Railroad operations in Sego began with the strategic incorporation of the Ballard & Thompson Railroad in 1911, establishing a significant 5.25-mile spur line that connected the town’s coal mines to the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad at Thompson Springs.

The railroad significance became evident as coal shipments reached 600-800 tons daily, transforming Sego from a remote camp into a thriving coal supplier.

You’ll find the transportation evolution reflected in the challenging infrastructure, with the line crossing Sego Creek 13 times.

The D&RGW took ownership in 1913, providing up to 9 round trips monthly during peak winter demand.

Though a small gas-mechanical railbus occasionally served passengers, the line’s primary purpose remained coal transport until dieselization in the 1950s reduced demand, ultimately leading to abandonment.

Cultural Diversity in Early Sego

Despite its remote location in eastern Utah, Sego’s cultural landscape emerged from a complex mix of Euro-American settlers, working-class miners, and company officials who shaped the town’s social fabric in the early 1890s.

The area’s deep indigenous heritage, visible in the surrounding canyon’s rock art, provided a backdrop for cultural exchanges between settlers and native populations, particularly regarding survival skills and resource knowledge.

- The American Fuel Company’s dominance created distinct social classes between management and laborers

- Immigrant contributions to the mining workforce diversified the town’s population

- Native American influence remained primarily visible through regional artifacts and the town’s name

- Company-provided facilities like stores and boarding houses centralized social interactions

While specific ethnic demographics aren’t well documented, Sego’s industrial nature likely attracted diverse workers seeking opportunity in the American West.

Ancient Rock Art and Native Heritage

While Sego’s ghost town status draws curious visitors today, the canyon’s true historical treasures date back thousands of years before the town’s existence.

You’ll find striking examples of ancient artistry in three distinct styles: Barrier Canyon (2000-6000 years old), Fremont (300-1300 AD), and Ute (1300-1600 AD).

The layered artwork reveals the canyon’s cultural significance as a long-term ceremonial site.

The oldest Barrier Canyon paintings feature haunting red figures with hollow eyes, while later Fremont petroglyphs showcase geometric patterns and human forms.

The most recent Ute artwork depicts horses and hunting scenes.

You can explore these remarkable panels just 15 minutes north of I-70, where they’ve endured as evidence of the region’s rich Native heritage.

Mining Operations and Peak Production

You’ll find the railroad infrastructure was essential to Sego’s development, with the Ballard & Thompson Railroad spur connecting the mine to the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad for coal transport.

During the peak production years of 1920-1940, you can trace how this railway connection enabled the mine to ship between 800 to 1,500 tons of coal daily to meet growing industrial demands.

The rail system’s efficiency helped Sego become Utah’s busiest coal camp by 1928, though this prosperity wouldn’t last beyond the 1940s.

Railroad Infrastructure Development

As Sego’s coal mining operations expanded in 1911, the Ballard & Thompson Railroad established an essential 5.25-mile connection between the mine and the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad at Thompson Springs.

The railroad construction required 13 trestle crossings over Sego Wash and cutting through Thompson Canyon, with varying rail weights to handle the challenging 4% grade.

- Initial track featured 3.3 miles of light 45-57 pound rail and heavier 65-pound rail for the remainder

- You’ll find a wye track at Thompson Springs that allowed steam locomotives to turn around

- Operational challenges included frequent derailments and track maintenance issues

- D&RGW provided all locomotive power and rolling stock by 1913, as Ballard & Thompson owned none

Peak Production Years 1920-1940

During the peak years of 1920-1940, Sego emerged as Utah’s busiest coal camp, reaching production levels of 1,500 tons daily by May 1928. The community dynamics centered around a workforce of 150 miners who braved hazardous underground conditions to support a population that peaked at 500 residents in the early 1920s.

Economic fluctuations dramatically shaped Sego’s trajectory during this period. While the 1920s saw robust growth, the Great Depression dealt significant blows to coal demand and prices.

The community’s resilience was tested as railroads began switching to diesel engines, further weakening the coal market. You’ll find that population numbers reflect these challenges, dropping from 223 in 1930 to 123 by 1940, marking the beginning of Sego’s eventual decline.

Water Challenges and Environmental Factors

While Sego’s mining operations initially showed promise, the town’s persistent water challenges ultimately sealed its fate.

You’ll find that water scarcity plagued daily operations, with the water table dropping steadily and local springs drying up. The town’s struggle intensified when flash floods repeatedly damaged critical infrastructure, leaving the railroad off-track up to 25% of the time.

Environmental degradation accelerated as mining operations stressed the already fragile desert ecosystem.

- The coal washer couldn’t operate when water slowed to a trickle

- Miners relied on small railroad pools for basic water needs

- Flash floods regularly damaged bridges and trestles

- Underground coal seam fires continue burning today

These harsh conditions drove away residents and eventually forced the mine’s closure, leaving behind a stark reminder of nature’s dominance over human ambition.

The Last Days of Coal Mining

Despite Sego’s high-quality coal deposits, the mining operation’s final chapter began unfolding in the 1930s through a perfect storm of challenges. The economic impact hit hard as coal prices plummeted during the Great Depression, while railroads shifted to diesel engines, devastating demand.

The 1930s ushered in Sego’s downfall as the Great Depression crushed coal prices and railroads abandoned steam for diesel power.

Labor struggles intensified when miners, frequently paid in company scrip, unionized with the United Mine Workers in 1933.

You can trace the mine’s decline through a series of crushing blows: the costly electricity installation in 1927, deteriorating railroad infrastructure, and finally, a devastating tipple fire in 1949.

Even when miners pooled resources to purchase the operation at sheriff’s auction in 1947, market conditions proved too difficult to overcome. By 1955, a Texas oil firm’s purchase marked coal mining’s end in Sego.

What Remains Today

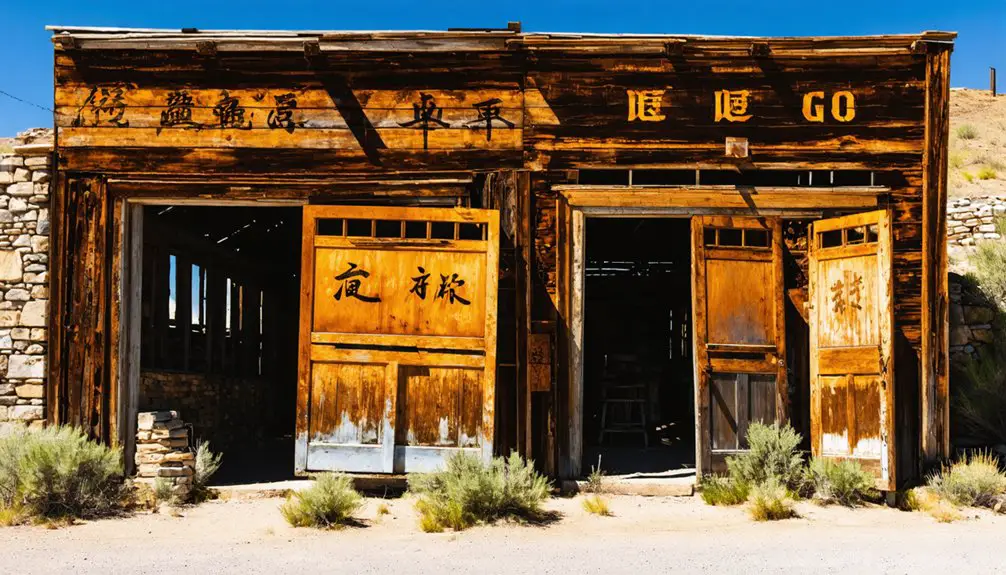

Today’s visitors to Sego encounter a haunting collection of weathered ruins scattered throughout the narrow canyon, where a solitary stone building stands as the most prominent survivor among the ghost town’s remains.

You’ll find foundations and dugouts marking where the boarding house and company store once thrived, while mining artifacts tell the story of the town’s coal-mining past. The Ballard-Sego Coal Mine Historic District, spanning over 5,000 acres, preserves these remaining structures and industrial relics.

- Historic railroad cuts and trestle foundations reveal former transportation routes

- Mining tools and equipment are preserved in the Silver Reef Museum

- Original mine entrances remain visible within Sego Canyon

- A single brick building stands among collapsed wooden structures

The site’s deteriorating condition, combined with limited access via dirt roads, makes Sego primarily attractive to dedicated ghost town explorers.

Preserving Sego’s Legacy

The preservation of Sego’s historical legacy faces mounting challenges as time and human activity take their toll on the ghost town’s remaining structures.

Since the town’s abandonment in the 1950s, you’ll find ongoing efforts to protect its historical significance hampered by vandalism, weather damage, and limited resources.

While the American Fuel Company Store‘s stone walls still stand as a symbol of Sego’s mining era, many wooden structures visible in the 1990s have now collapsed.

Preservation initiatives focus on protecting both the town’s remains and nearby prehistoric petroglyphs, which date back to 600 A.D.

You’ll notice interpretive signage and controlled pathways that help educate visitors about this dual heritage.

The BLM works with local historical societies to manage access while preventing further deterioration of these irreplaceable cultural resources.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Major Mining Accidents or Deaths Recorded in Sego?

You won’t find records of major mining accidents or deaths in mining safety reports. While fires damaged equipment and infrastructure, there’s no documentation of fatalities in available accident reports.

What Happened to the Families Who Lived in Sego After Abandonment?

Like scattered leaves in the wind, you’ll find these families spread across Utah, with many settling in Moab and Thompson Springs, maintaining their Sego history through reunions and relocating their homes.

Did Sego Have a School or Church During Its Operational Years?

You’ll find a one-room schoolhouse from 1907 in Sego’s history, still standing today. While there’s no evidence of formal churches, the diverse community likely held informal religious gatherings elsewhere.

Are There Any Surviving Former Residents of Sego Still Alive Today?

Based on Sego history research, you won’t find documented surviving residents today. Given the town’s abandonment in 1955, most former residents would now be deceased or well over 80 years old.

Was Gold or Silver Ever Discovered in the Sego Mining Area?

Unlike the glittering gold rush towns that dot the West, you won’t find any precious metal discoveries in Sego’s history. Mining techniques here focused purely on extracting coal for railroad fuel.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sego

- https://www.moabhappenings.com/Archives/pioneer0411.htm

- https://moabsunnews.com/2021/11/11/grand-countys-ghost-towns-boom-and-bust-in-sego/

- https://www.roadtripryan.com/go/t/utah/moab/sego-ghost-town

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ut-segocanyon/

- https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2019/02/03/in-the-middle-of-time-thompson-and-sego-utah-herm-hoops/

- https://moabsunnews.com/2023/02/16/david-price-sego-canyon/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/sego-utah

- https://wereintherockies.com/sego-canyon/

- https://cheapmotelsandahotplate.org/2012/11/28/sego-canyon-rock-art-glory-mining-town-ruins/