You’ll discover Shakespeare, New Mexico as a remarkably preserved ghost town founded in 1870 during the silver mining boom. Originally named Ralston, this frontier settlement peaked at 3,000 residents before declining when the railroad bypassed it. The town’s authentic buildings, including the historic Stratford Hotel and Grant House, showcase its vigilante justice era under “Dangerous Dan” Tucker. Shakespeare’s designation as a National Historic Site guarantees its architectural legacy continues to tell tales of America’s Wild West.

Key Takeaways

- Shakespeare was founded in 1870 as a silver mining town, growing from 200 to 3,000 residents before declining when bypassed by railroad.

- The town is now preserved as a National Historic Site, featuring original structures including the Grant House and Stratford Hotel.

- Shakespeare was known for its vigilante justice system led by “Dangerous Dan” Tucker and the Shakespeare Guard during lawless frontier days.

- Three generations of women preserved the town’s history, with Rita Wells Hill purchasing it in 1935 as a working ranch.

- Visitors can explore authentic 19th-century buildings showcasing a blend of Greek Revival and Mexican Village architectural styles.

A Mining Town’s Journey Through Time

While prospectors had been drawn to numerous mining towns across New Mexico in the late 1800s, Shakespeare’s story began around 1870 when silver ore deposits attracted fortune seekers to the area. Similar to the early miners of Taos County who experienced minimal initial rewards, early prospecting in Shakespeare proved challenging.

You’ll find that mining techniques evolved from basic prospecting to more organized operations when financier William Ralston backed the New Mexico Mining Company’s efforts. The settlement, initially named Ralston, grew from 200 tent-dwelling inhabitants to a bustling community of 3,000 as news spread through San Francisco and San Diego papers.

The cultural impact deepened in 1879 when Colonel Boyle transformed the town, now renamed Shakespeare, by establishing multiple mining companies and constructing adobe buildings, including the iconic Stratford Hotel, marking the shift from temporary camp to established community. The town’s decline accelerated when the railroad bypassed Shakespeare, redirecting economic activity to nearby Lordsburg.

The Many Names of Shakespeare

Before emerging as the ghost town we recognize today, Shakespeare underwent several name changes that reflected its evolving role in New Mexico’s frontier history.

The original site served as a crucial Army mail relay station established around 1856.

These historical shifts reveal the settlement’s dynamic transformation from a crucial spring to a bustling mining town, much like how national poet William Shakespeare transformed from actor to playwright in London.

- Mexican Springs marked the location’s earliest naming significance, highlighting a natural water source that drew Native Americans and travelers.

- After the Civil War, the site became known as Grant, honoring the famous general.

- Around 1870, the name changed to Ralston, reflecting financier William Ralston’s influence during the silver mining boom.

- Finally, in 1879, the settlement adopted Shakespeare as its permanent identity, coinciding with a second mining surge that would define its lasting legacy.

Life in the Wild West Mining Camp

Life in Shakespeare embodied the quintessential Wild West mining experience, where three distinct phases of development shaped the town’s character. You’d have witnessed the evolution from a tent settlement to adobe structures as mining lifestyles transformed from speculative ventures to legitimate operations under Colonel Boyle’s leadership.

Daily existence centered around the vital spring water supply and mining activities, while frontier challenges included Apache raids and the need for self-organized defense through the Shakespeare Brigade. Originally called Mexican Springs, the settlement served as an important rest stop for Army mail carriers traversing the dangerous frontier.

Though the population swelled to an estimated 3,000 during peak mining periods, you wouldn’t have found churches or schools in this rough-and-tumble community. Instead, social life revolved around establishments like the Stratford Hotel, where miners, soldiers, and travelers gathered after long days of working the silver and gold claims.

Law and Order on the Frontier

You’ll discover that Shakespeare’s law enforcement shifted from formal authority to vigilante justice under the iron-fisted rule of “Dangerous Dan” Tucker, who served as both Justice of the Peace and coroner in the 1870s.

When Tucker couldn’t maintain order alone, the Shakespeare Guard emerged as a vigilance committee that conducted swift trials and carried out punishments, including the notorious 1879 double lynching of two suspected rustlers at the Grant House. This was decades before the New Mexico Mounted Police would be established to bring formal law enforcement to the territory.

Despite the harsh methods, the vigilante system effectively deterred crime in the remote mining settlement where traditional law enforcement structures proved inadequate.

Dangerous Dan’s Iron Rule

While many frontier towns struggled with lawlessness in the 1880s, Shakespeare, New Mexico, maintained order through the iron-fisted rule of Marshal Dan Tucker, nicknamed “Dangerous Dan” for his swift and uncompromising approach to justice.

His shoot-first philosophy and proven marksmanship earned respect throughout the territory, making his mere presence enough to scatter outlaw gangs. During his career, he admitted to killing eight men while serving as deputy sheriff.

- You’d find Tucker patrolling with his double-barreled shotgun, ready for immediate confrontation with lawbreakers.

- He’d travel up to 60 miles to face down criminal threats, as he did in Deming during 1881.

- His law enforcement tactics focused on direct action rather than cautious negotiation.

- His methods complemented Shakespeare’s harsh frontier justice system, where vigilantes often handled punishment through public hangings at the Grant House.

Infamous Double Lynching

Under Dangerous Dan Tucker‘s watch, one of Shakespeare’s most notorious incidents unfolded on November 9, 1881, when vigilantes hanged two cattle rustlers at the Grant House stage station.

The victims, Sandy King and “Russian Bill” Tattenbaum, had ties to the infamous Clanton faction from Charleston, Arizona Territory.

The lynching legacy of this event perfectly captures the raw nature of frontier justice in New Mexico’s mining boomtowns.

While Shakespeare was attempting to establish formal law enforcement, including plans for a constable and jail, vigilantes took matters into their own hands.

They left the bodies hanging for days as a stark warning to other outlaws.

You’ll find conflicting accounts of the arrests and authority involved, but the message was clear – lawlessness wouldn’t be tolerated in Shakespeare’s volatile silver mining community.

Justice Through Vigilantism

Because Shakespeare lacked formal law enforcement institutions like police departments, schools, and churches, citizens assumed the role of maintaining order through vigilante justice. The community’s approach to law enforcement relied heavily on direct action and swift punishment, often bypassing formal legal proceedings entirely.

1. You’d find vigilante groups organizing themselves into militias like the Shakespeare Guard, which consisted of up to 70 citizens who defended against both criminal elements and Apache raids.

2. Community enforcement often centered around public displays of punishment at locations like the Grant House.

3. You’d witness bodies of offenders left hanging as warnings to other potential wrongdoers.

Notable examples include the hanging of Russian Bill and King in 1881 for their criminal activities.

4. While Deputy Sheriff Dan Tucker maintained some official presence, the community’s vigilante justice system frequently overrode his authority.

This form of frontier justice was common throughout the New Mexico Territory before its admission as a state in 1912.

Military Heritage and Strategic Importance

As a strategically positioned frontier settlement, Shakespeare played an essential military role in the American Southwest during the late 19th century.

You’ll find evidence of military influence in the U.S. Army’s mid-1850s relay station, which supported vital mail routes between Fort Thorn and Fort Buchanan. The town’s reliable spring made it indispensable for military logistics and strategic defense.

You can trace Shakespeare’s military heritage through the Shakespeare Guards, a local militia formed in 1879 to counter Apache threats. Under Captain J. E. Price’s leadership, these 32 enlisted men protected the mining community until 1885.

During the Civil War, both Confederate and Union forces utilized the settlement, including Colonel Sherod Hunter’s Texan force en route to California’s gold fields.

The town’s military significance helped secure its place on the National Register of Historic Places.

Preserving a Piece of American History

You’ll find a remarkable story of preservation in Shakespeare, where three generations of women—Emma Marble Muir, Rita Wells Hill, and Janaloo Hill Hough—dedicated their lives to protecting this piece of American history.

Through their meticulous stewardship, these women maintained the town’s original adobe structures, including the Grant House, Stratford Hotel, and blacksmith shop, while documenting essential historical knowledge from early residents like “Uncle” Johnny Evenson.

Their efforts culminated in Shakespeare’s designation as a National Historic Site in 1970, ensuring the ghost town’s architectural authenticity and cultural legacy remain intact for future generations to study. After a devastating fire in 1997, Janaloo Hill Hough and her husband Emanuel worked tirelessly to restore the town to its former glory.

Three Generations of Stewardship

The remarkable preservation of Shakespeare Ghost Town stands as a tribute to three generations of dedicated female stewards who protected this slice of American frontier history.

Their family legacy began in 1882 when Emma Marble Muir arrived and documented firsthand accounts from original residents. Historical preservation continued when Rita Wells Hill purchased the town in 1935 with her husband Frank, transforming it into a working ranch while maintaining its authenticity.

- Emma Marble Muir established the foundation by collecting oral histories and artifacts

- Rita Wells Hill and her daughter Janaloo maintained the site’s integrity after Frank’s death in 1970

- Janaloo and Manny Hough secured National Historic Site designation

- Their daughter Gina and her husband now manage daily operations and educational programs

Authentic Building Conservation

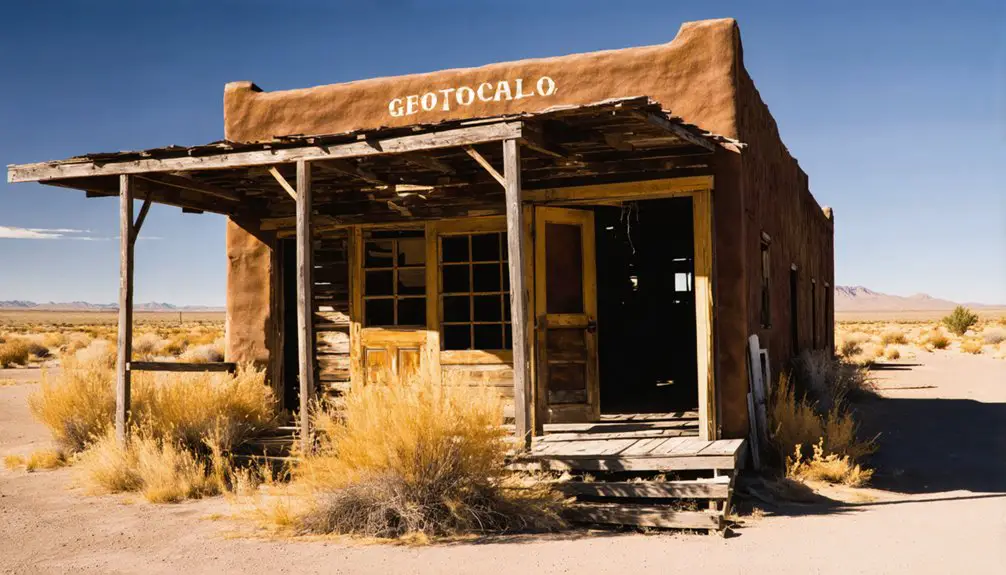

Standing as a testimony to meticulous preservation efforts, Shakespeare’s original structures from the late 19th and early 20th centuries maintain their architectural authenticity through carefully implemented conservation techniques.

You’ll find historical restoration projects that honor the town’s Greek Revival and Mexican Village styles while protecting original materials in landmarks like the Grant House and Stratford Hotel.

Conservation techniques focus on stabilizing aged wood, adobe, and masonry against harsh desert conditions.

When you explore the buildings, you’ll notice period-appropriate repairs that preserve original craftsmanship.

The 1914-1923 Company Mining House, relocated from Santa Rita Copper Mine, demonstrates how strategic intervention can save threatened structures.

Extensive documentation, including National Register records and architectural surveys, guides these preservation efforts, ensuring Shakespeare’s authenticity remains intact for future generations.

Ghost Town Architecture and Original Buildings

Located along the rugged New Mexico frontier, Shakespeare’s architectural significance represents a compelling blend of Greek Revival and Mexican Village influences, earning the town prestigious spots on both the National Register of Historic Places and New Mexico State Register of Cultural Properties.

Shakespeare stands as a remarkable fusion of frontier architecture, where Greek Revival grandeur meets Mexican Village charm along New Mexico’s historic borderlands.

Historical preservation efforts by the Hill family since 1935 have maintained the town’s authentic character, showcasing original construction methods and materials.

You’ll discover these authentic structures throughout the town:

- Grant House – a former stagecoach station and saloon that served as a crucial community hub

- Stratford Hotel – dating to the late 1800s, with connections to Billy the Kid

- Assay Office – rebuilt in 1879 for testing precious metal ores

- Supporting structures – including the blacksmith shop and powder magazine, essential to mining operations

Planning Your Visit to Shakespeare

Nestled just outside Lordsburg in southwestern New Mexico, Shakespeare ghost town welcomes visitors through structured guided tours that illuminate its rich mining and frontier heritage.

To plan your visit, you’ll need to reserve a spot on either monthly public tours ($5 for adults, $3 for children) or daily private tours ($7 for adults, $3 for children).

Essential travel tips include bringing sunscreen and water, as the arid climate can be challenging. Tours run at 10 AM, 12 PM, and 3 PM MDT, lasting approximately 90 minutes.

Following visitor guidelines, you’ll need to schedule in advance by calling 575-542-9034.

While on-site amenities are minimal, you’ll find cold well water, shaded seating, and restrooms at the visitor center. Additional services are available 2.5 miles away in Lordsburg.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to William Chapman Ralston After the Town Bore His Name?

Following his name’s placement on the town, Ralston’s legacy ended dramatically when he died in 1875’s San Francisco Bay. You’ll find 50,000 people attended his funeral, marking his post town life’s end.

Are There Any Documented Paranormal Activities or Ghost Sightings in Shakespeare?

You won’t find officially documented ghost encounters or spectral sightings in reliable records, though local folklore includes unverified claims shared during tours and storytelling events at the historic buildings.

How Many People Lived in Shakespeare During Its Peak Population?

You’ll find conflicting claims about peak population in town history, but census records and newspaper reports suggest it reached between 150-300 residents, not the commonly exaggerated figure of 3,000.

Which Movies or Television Shows Have Been Filmed in Shakespeare?

You’ll find mostly independent projects and documentaries using these film locations, with some silent films from Rita Wells Hill’s era and modern ghost stories featuring the authentic western buildings.

What Artifacts From Shakespeare’s Mining Era Can Be Found in Museums?

In museums bursting with countless treasures, you’ll find essential mining tools like pickaxes and ore carts, plus valuable historical documents including company ledgers, photographs, and promotional materials from frontier mining operations.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakespeare

- https://www.nmhistoricwomen.org/new-mexico-historic-women/women-of-shakespeare-emma-marble-muir-rita-wells-hill-janaloo-hill-hough/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/nm-shakespeare/

- https://gregdisch.com/2021/03/27/shakespeare-ghost-town/

- https://www.skwhee.com/2023/01/shakespeare-ghost-town/

- https://agmc.info/wp-content/uploads/simple-file-list/New-Mexico-documents/New_Mexico_Mining_History.pdf

- https://redrivernmhistoricalsociety.org/1867-1905-mining-days/

- https://www.shakespeareghostown.com/about-shakespeare

- https://www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/ghost-towns/shakespeare/

- https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2045&context=nmhr