Socatoon Station emerged in 1858 as a critical Butterfield Overland Mail stop near present-day Sacaton, Arizona. You’ll find it served as an essential waypoint where weary travelers received fresh horses, simple meals, and brief rest. Water management proved crucial to its survival in the harsh desert climate. The Civil War disrupted operations, and upstream water diversions ultimately led to its abandonment in the 1870s. The station’s ruins tell a deeper story of America’s westward expansion.

Key Takeaways

- Socatoon Station emerged in 1858 as a crucial waypoint on the Butterfield Overland Mail route in Arizona Territory.

- Located four miles east of Sacaton near Pima and Maricopa villages, it served as a vital communication and supply post.

- The station declined during the Civil War when operations were disrupted by territorial conflicts between Union and Confederate forces.

- Water scarcity from upstream diversions along the Gila River ultimately led to the station’s abandonment.

- The ghost town represents America’s westward expansion and the challenges faced by frontier settlements in the harsh desert climate.

The Birth of a Frontier Waypoint (1858)

In the pivotal year of 1858, Socatoon Station emerged from the recently acquired Gadsden Purchase territory as a critical frontier waypoint along the ambitious Butterfield Overland Mail route.

Located just four miles east of Sacaton, the station strategically positioned itself near established Pima and Maricopa villages, tapping into indigenous trade networks and reliable water sources.

You’d recognize this development as part of America’s broader Manifest Destiny policies, with the 1854 Gadsden Purchase creating new opportunities for westward expansion.

The station’s construction reflected the nation’s commitment to establishing communication infrastructure across remote territories. Much like the Butterfield Division Superintendent William Buckley oversaw operations at various stations including Dragoon Springs, ensuring their strategic functionality.

Like other Butterfield stations spaced approximately 20 miles apart, Socatoon provided fresh horses, supplies, and rest for weary travelers traversing the harsh 2,795-mile route between Missouri and California, becoming an essential lifeline in Arizona’s frontier development.

Before becoming a Butterfield station, it served as a stopping place for the San Antonio-San Diego Mail in 1857-58.

Life Along the Butterfield Overland Mail Route

In the daily operations of Butterfield stations like Socatoon, you’d witness a carefully orchestrated exchange of exhausted horses for fresh teams while station keepers hastily prepared simple meals for weary passengers.

As you traveled this desolate stretch, dangers constantly threatened your journey, from Apache raids near strategic water sources to the punishing elements that could trap coaches in flash floods or scorching heat. The strategic placement of stations twenty miles apart ensured travelers wouldn’t be stranded too long in this harsh landscape.

The precious mail pouches you might observe being transferred represented the station’s primary purpose—maintaining communication links across the frontier despite frequent delays caused by washed-out roads, broken equipment, and the ever-present threat of attack. The Concord coaches used on this route were specially designed for durability, capable of carrying nine passengers inside with additional travelers perched precariously on the roof during the grueling 22-day journey.

Daily Station Operations

Life along the Butterfield Overland Mail Route centered around precisely coordinated station operations that maintained the mail service’s ambitious schedule.

Station logistics demanded constant readiness, with workers perpetually preparing for the next coach’s arrival—storing hay, securing water supplies, and ensuring mail was organized for swift transfer.

You’d witness a flurry of activity when a stagecoach appeared on the horizon. Within minutes of arrival, exhausted horses were unhitched while fresh teams were brought forward.

Horse care was paramount; station hands watered, fed, and examined each animal meticulously, understanding that the entire operation depended on their strength and health.

Passengers received brief respite to take simple meals while drivers exchanged information about trail conditions ahead. The entire journey from the east coast to California took approximately 25 days across the 2,800-mile route.

Within 10-15 minutes, the coach would depart, continuing the relentless 24-hour cycle that connected East to West. The Butterfield Overland Mail contained 12 official stations throughout the Choctaw Nation, each serving as crucial infrastructure nodes across Indian Territory.

Dangers Facing Travelers

While stagecoach passengers enthusiastically anticipated the western frontier’s promise, they faced formidable dangers that transformed each journey into a test of survival.

Your greatest threats weren’t outlaws—Butterfield’s no-valuables policy effectively deterred robberies—but rather environmental threats and hostile encounters.

Apache raids at stations like Socatoon presented constant danger, especially after the 1861 Bascom Affair escalated tensions.

You’d face isolation in vast stretches between stations, with help potentially days away if travel hazards struck.

Wild, poorly trained animals pulling coaches caused numerous accidents—the leading cause of passenger fatalities.

Arizona’s harsh conditions subjected you to extreme heat, dehydration, and unpredictable terrain.

You’d navigate overflows, rockslides, and impassable creeks while battling the elements—all without the security of modern communication or rescue options.

The journey typically utilized celerity wagons for 70% of the trail, specially designed to withstand rough terrain while providing minimal comfort to passengers.

Before Butterfield’s operations ceased in March 1861, the Giddings brothers had established armed escorts for their coaches as they traversed the dangerous Apache territories.

Mail Delivery Challenges

Transforming communication across the frontier, the Butterfield Overland Mail route established unprecedented reliability with its twice-weekly delivery schedule—a remarkable advancement that shortened correspondence time from months to just weeks.

At Socatoon and 25 other Arizona stations, you’d witness the precision of logistical coordination as stagecoaches arrived for rapid horse changes, mail transfers, and brief passenger respites.

The 21.5-day average delivery time by 1859 represented triumph over formidable obstacles: scorching desert heat threatened mail security, while mountainous terrain required meticulous planning and execution.

Each station, positioned approximately 20 miles apart, formed a critical link in this 2,800-mile lifeline connecting St. Louis to San Francisco.

Despite lasting only three years, the Butterfield route’s legacy endured, demonstrating how strategic infrastructure could overcome wilderness isolation and unite a developing nation. The service maintained an impressive safety record with no fatalities reported during its operation, despite occasional threats from outlaws and indigenous tribes. The specially designed Butterfield stagecoaches featured strong sub-frames and padded seating to enhance passenger comfort during the arduous journey.

Daily Operations at a Desert Stagecoach Stop

Water management proved the most critical challenge at Socatoon Station, where staff meticulously rationed the precious desert resource for travelers, livestock, and cooking needs.

You’d find strict protocols governing passenger rest periods, typically limited to 20-30 minutes while horses were changed and mail was transferred, though overnight stays were accommodated when necessary.

The station’s daily rhythm centered around these carefully timed arrivals and departures, with every staff member’s duties precisely coordinated to guarantee efficient service despite the harsh Pinal County environment.

Water Management Challenges

Due to the harsh desert climate surrounding Socatoon Station, managing water resources presented one of the most formidable challenges for daily stagecoach operations.

You’d find the station’s survival depended on careful water rights negotiations with indigenous communities and upstream settlers who diverted precious Gila River flows.

- Cisterns and covered earthen reservoirs employed native mud-lining storage techniques to minimize evaporation.

- Manual drawing or gravity-fed systems compensated for the absence of modern pumping technology.

- Daily rationing prioritized essential needs: human consumption, livestock watering, and stagecoach requirements.

- Maintenance crews constantly repaired erosion and seepage in the earthen canal infrastructure.

- Contingency plans addressed periodic droughts and flash floods that threatened water security.

The station’s water management required meticulous attention to storage, usage, and infrastructure maintenance while adapting to unpredictable environmental conditions.

Passenger Rest Protocols

Socatoon Station’s passenger rest protocols followed a precise choreography of operations that balanced efficiency with traveler needs. You’d enter the station after dusty hours crossing desert terrain, surrendering your ticket for verification before being assigned a resting area.

Rest facilities, though spartan by modern standards, provided essential respite during the arduous journey. You’d receive a designated time slot for meals, typically served in shifts to accommodate all travelers.

During Apache conflict periods, armed personnel would monitor your safety while station hands tended to horse exchanges.

Passenger comfort remained secondary to maintaining the mail schedule, yet protocols guaranteed basic needs were met. You’d follow strict wake-up calls coordinated with departure times, allowing just enough recovery before continuing your westward journey through Arizona’s unforgiving landscape.

Water Sources and Survival in the Arizona Territory

Surviving in the harsh Arizona Territory required access to reliable water sources, a challenge that shaped settlement patterns long before European arrival. The Hohokam established North America’s only “true irrigation culture” around 200 A.D., creating complex canal networks that later settlers would rediscover.

- Ancient irrigation systems supported settlements where Phoenix, Tempe, and Mesa now stand.

- By the 1880s, over 25,000 acres received irrigation through carefully engineered branch canals.

- The 1890s drought reduced Salt River flow to just 25 cubic feet per second.

- Watershed destruction from cattle, lumber, and mining industries dramatically altered water availability.

- Roosevelt Dam’s 1911 completion revolutionized water conservation in the territory.

When you traveled through early Arizona, your survival depended on understanding these irrigation techniques and respecting the fragile balance of the desert’s hydrological systems.

The Civil War’s Impact on Socatoon Station

When the American Civil War erupted in 1861, it dramatically altered the fate of Socatoon Station and other outposts along the Butterfield Overland Mail route. The Butterfield line ceased operations, severing essential communication networks in the Southwest.

You’d find Socatoon Station caught in a territorial tug-of-war as Confederate forces established the Confederate States Territory of Arizona, dividing it along the 34th parallel. Captain Sherod Hunter‘s Confederate troops systematically destroyed stagecoach stations westward from Tucson to prevent Union advancement, likely impacting Socatoon Station.

Later, Colonel James Carleton‘s California Column of Union volunteers advanced through the territory, following the abandoned Butterfield route. The station’s strategic position made it a potential flashpoint in this desert campaign, while concurrent Apache resistance complicated military movements for both sides in the contested region.

Decline and Abandonment in the 1870s

Throughout the 1870s, Socatoon Station faced a devastating decline triggered by systematic water diversion upstream along the Gila River. You’d have witnessed the immediate collapse of local O’otham and Pee-Posh farming operations as settlers in upper valleys redirected the lifeblood of indigenous communities.

Water scarcity transformed the region’s landscape both physically and culturally:

- Mass famine devastated populations between 1880-1920

- Emergency government rations introduced processed foods, sparking health crises

- Cultural traditions vanished as communities dispersed

- Economic depression forced widespread poverty

- Alcoholism emerged amid social deterioration

The stagecoach station itself became unsustainable as regional abandonment accelerated.

As water vanished, so too did the station, its viability collapsing amid the region’s rapid desertion.

This period represents the darkest chapter in the area’s history, with water theft creating cascading failures across all aspects of life. Many residents migrated toward Salt River Valley, though they’d ultimately face similar challenges there.

Archaeological Remnants and Historical Significance

Archaeological excavations at Socatoon Station have unearthed a significant collection of material remnants that document the site’s brief but essential role in Arizona’s territorial transportation network.

When you visit today, you’ll find archaeological findings that include structural foundations, pottery fragments, and metal hardware from the 1858-1861 operational period.

Researchers have meticulously cataloged historical artifacts using ground-level surveys and comparative analysis with other Butterfield Overland Mail stations. The collected evidence reveals how this station functioned as a crucial communication link connecting eastern and western United States before Civil War disruptions.

The site’s preservation offers unique insights into frontier infrastructure development.

These remnants aren’t just historical curiosities—they’re tangible connections to the transcontinental mail system that helped shape territorial Arizona’s development during a pivotal pre-Civil War period.

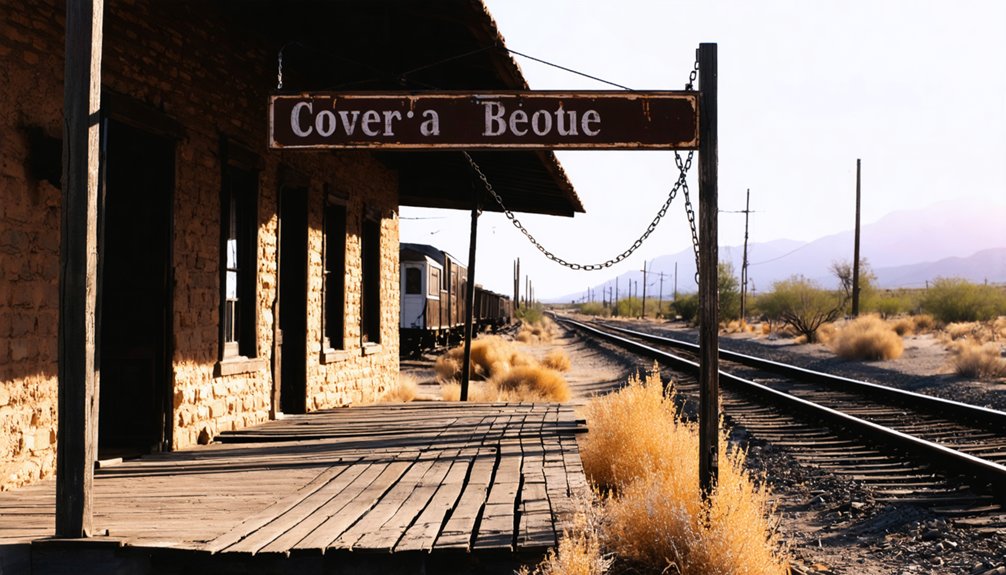

Visiting the Ghost Station Near Modern Sacaton

While the archaeological value of Socatoon Station offers scholarly insight into territorial Arizona’s development, modern visitors often wonder how to experience this historical site firsthand.

Located approximately four miles east of modern Sacaton, this barren site requires thoughtful visitor preparation before your journey. The station’s site accessibility is limited, with no formal trails or facilities marking this once-important stagecoach stop.

- Personal vehicle required—no public transportation serves the remote location

- Prepare for desert conditions with adequate water and sun protection

- Visit during cooler months to avoid dangerous heat exposure

- Respect the site’s proximity to Native American tribal lands

- Stop in modern Sacaton for supplies before heading to the ghost site

The minimal physical remnants demand historical imagination, connecting you with Arizona’s pioneer past despite the absence of standing structures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Notable Gunfights or Crimes Recorded at Socatoon Station?

Despite what Netflix might show, you won’t find any gunfight history or crime incidents at Socatoon Station. Historical records document no significant violent confrontations, robberies, or murders during its 1858-1861 operational period.

What Indigenous Tribes Interacted With the Station and How?

You’ll find the Akimel O’otham (Pima) and Pee Posh (Maricopa) tribes engaged with Socatoon Station through complex tribal interactions, including water resource negotiations and limited cultural exchanges during its 1858-1861 operational period.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Ever Stay at Socatoon?

You’ll find no documented famous visitors at Socatoon. While the station hosted travelers during significant historical events like the Civil War, records don’t identify any notable historical figures staying there.

What Personal Items Have Archaeologists Recovered From the Site?

Archaeological findings at the site reveal diverse personal artifacts including knives, buckles, a turquoise pendant, pyrite ring, beads, and porcelain doorknobs—evidence of both early indigenous inhabitants and later occupants.

How Did Extreme Weather Events Affect the Station’s Operations?

Weather kept the station on its toes. You’d face operational challenges from scorching heat damaging equipment, flash floods washing out roads, and droughts limiting water supplies, chronologically testing your resilience throughout the year.

References

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l_ogVgvyw7Y

- https://www.visittucson.org/blog/post/8-ghost-towns-of-southern-arizona/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socatoon_Station

- https://library.brown.edu/cds/aravaipa/get_gloss.php?id=sacaton

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacaton

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dragoon_Springs_Stage_Station_Site

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Socatoon_Station

- https://southernarizonaguide.com/butterfield-overland-mail-company-and-the-dragoon-springs-stage-station/