You’ll find Stillwater’s ghostly remains in Churchill County, Nevada, where it thrived as the county seat from 1868 to 1904. Originally established in 1862 as a stage station, this frontier settlement grew to include a courthouse, hotels, and bustling commerce. Today, stone foundations and adobe ruins mark where this once-vital hub stood, while the surrounding 79,570-acre wildlife refuge preserves both the area’s natural heritage and its historic remnants. The site’s layers of history await your exploration.

Key Takeaways

- Stillwater transformed from Churchill County’s seat into a ghost town after losing its administrative status to Fallon in 1903.

- Established in 1862 as a stagecoach station, Stillwater once thrived with 150 residents, hotels, and essential civic buildings.

- Historical remnants include stone foundations, adobe ruins, fence lines, and irrigation ditches from its frontier settlement period.

- The town’s original wooden courthouse from 1869 and the Sanford Hotel represent key architectural remains of its prosperous era.

- The area now primarily serves as the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, protecting 79,570 acres of wetland habitats.

Northern Paiute Heritage and First Settlements

Before Stillwater became a ghost town, the Northern Paiute people called this region home for thousands of years, establishing a sophisticated society adapted to the harsh Great Basin environment.

You’ll find evidence of their cultural resilience in how they organized into small, mobile groups of 3-5 households, following seasonal migrations to harvest plants and hunt game. Their Paiute traditions centered on council-based decision making, with leaders called niaves providing guidance rather than autocratic rule. The respected activist and leader Sarah Winnemucca, born as Thocmetony, fought tirelessly to protect her people’s rights.

Northern Paiute communities thrived through adaptable family groups and democratic leadership, moving with the seasons to sustain their way of life.

Archaeological findings, including the Spirit Cave Man remains from over 9,400 years ago, confirm their deep connection to this land.

Through oral histories, drum ceremonies, and dances, they preserved their cultural knowledge, maintaining a sustainable lifestyle that balanced hunting deer and rabbits with gathering seeds, nuts, and roots from the desert landscape. The arrival of settlers disrupted their traditional way of life when livestock trampled vegetation that the Paiute people relied upon for sustenance.

The Rise of a Frontier Stage Station

While the Northern Paiute people maintained their ancestral presence in the region, a new chapter began in July 1862 when the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company established the Stillwater Stage Station.

Named after the sluggish Stillwater Slough, this crucial hub quickly became essential to stagecoach routes connecting the American West.

You’ll find that J.C. Scott’s arrival in autumn 1862 sparked the community’s growth, leading to innovative agricultural developments through irrigation systems.

By 1868, the settlement had grown to 150 residents, boasting a courthouse, hotels, and numerous businesses. The establishment of the post office in 1865 marked a significant milestone in Stillwater’s development as an official community.

The Sanford Hotel was built in 1870, replacing a tent hotel that had previously served travelers.

The station’s strategic location along key transportation corridors fostered agricultural innovations that sustained both local inhabitants and passing travelers, transforming a simple way station into a thriving frontier community.

Birth of Churchill County’s Original Seat

You’ll find that Stillwater’s early pioneer settlement followed a pattern common to frontier towns, with hardy settlers drawn to the valley’s tranquil pools and agricultural potential.

When Churchill County established its government in 1861, officials initially placed the county seat in La Plata before moving it briefly to Bucklands and then permanently to Stillwater in 1868.

The construction of Stillwater’s first courthouse in 1869 – a modest 16×24-foot wooden structure that doubled as a schoolhouse – marked the town’s emergence as a center of regional authority.

The settlers developed one of Nevada’s earliest irrigation systems to sustain their agricultural endeavors.

The town became an important stopover for early gold prospectors traveling through Churchill County on their way to seek fortune in California.

Early Pioneer Settlement Pattern

Once inhabited by Northern Paiute people who thrived on the Carson Sink’s abundant marshland resources, Stillwater’s pioneer settlement began in autumn 1862 with J.C. Scott.

The settlement dynamics shifted rapidly when W.H. Dowd and Moses Job arrived in spring 1863, followed by William Page and J.G. Hughes, drawn to the fertile valley’s agricultural promise.

You’ll find the pioneer challenges they faced were met with remarkable ingenuity. They established the Overland Stage Station in July 1862, making Stillwater a vital hub for travel and mail.

Within five years, you’d have seen a bustling community of 150 residents developing irrigation ditches and fencing to support farming operations.

The settlers’ determination transformed the harsh desert landscape into productive farmland, proving their resilience in taming Nevada’s unforgiving terrain. The scarcity of materials meant early residents faced high building costs while establishing their homesteads.

County Government Takes Root

Established in 1861 as one of Nevada’s original counties, Churchill County commenced on a complex journey to find its permanent seat of government.

You’ll find that the county’s first seat was at Bucklands Station, but this location didn’t last long as it became part of Lyon County by 1864.

The seat then shifted to La Plata, where a wooden courthouse served the region’s needs.

When La Plata’s influence waned, Stillwater gained political influence in 1868, establishing a more permanent government presence with its two-story courthouse built in 1870. The early economy of Stillwater was sustained by farming and freight stations. Multiple entities sharing the name “Churchill County” required careful disambiguation in historical records.

Despite threats to dissolve Churchill County due to its small population, local leaders like Assemblyman Lemuel Allen fought to maintain its independence.

This period of administrative musical chairs wouldn’t end until Fallon emerged as the final county seat in 1903.

Courthouse Establishes Regional Authority

While Churchill County‘s governmental journey began in 1861, its first true seat of authority emerged in La Plata during 1864 when the county formally organized its administrative functions.

You’ll find that the county’s governance evolution soon shifted to Buckland’s Station, then to Stillwater in 1868, where a wooden courthouse was constructed in 1869 and later rebuilt in 1881.

The courthouse significance reached its pinnacle in 1903 when Fallon became the new county seat, marked by the construction of Nevada’s only monumental wooden courthouse.

This Neo-Classical structure, designed by Benjamin Leon for $7,300, featured Ionic columns and a balcony, symbolizing the shift from frontier justice to established regional authority.

It’s still serving the community today, representing over a century of stable local governance.

The building now serves as law enforcement offices while maintaining its historical significance within the county complex.

Golden Era of Commerce and Community

During the 1870s and 1880s, Stillwater reached its zenith as a thriving commercial hub and administrative center of Churchill County. You’d have found golden opportunities in agriculture, where one of Nevada’s earliest irrigation systems enabled farmers to supply produce to bustling mining camps.

The vibrant community dynamics centered around crucial businesses, including the newly built Sanford Hotel, a busy saloon, and a blacksmith shop serving travelers and locals alike.

The town’s prosperity reflected in its infrastructure growth, with the construction of a grammar school in 1872 and a new two-story wooden courthouse in 1881.

As the county seat, Stillwater’s population swelled, and you’d have witnessed a dynamic mix of stage travelers, farmers, merchants, and government officials all contributing to the town’s peak economic significance.

Environmental Legacy and Wildlife Refuge

You’ll find the environmental legacy of Stillwater most evident in its 22,000-acre wildlife refuge, established in 1948 to protect critical wetland habitats in the Carson Sink ecosystem.

The refuge’s marshlands serve as essential stopping points for migratory birds while supporting diverse native species including waterfowl and small mammals adapted to the semi-arid environment.

Through careful management and restoration efforts, these protected wetlands continue to thrive despite the area’s history of mining operations and the challenges posed by seasonal water fluctuations.

Wetland Habitat Restoration

Since the passage of the 1990 settlement act, extensive wetland restoration efforts have transformed Stillwater’s environmental legacy through strategic water rights acquisitions and habitat management.

You’ll find that agencies have secured over 49,040 acre-feet of water rights, with the majority dedicated to sustaining wetland ecosystems within the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge.

Through careful engineering of canals and ponds, these restored wetlands now support diverse wildlife populations, from fish-eating pelicans to various waterfowl species.

The refuge’s varied habitats, ranging from freshwater to saline ponds, showcase successful habitat restoration techniques.

You can observe how the integration of monitoring systems and assessment tools has strengthened conservation efforts, while partnerships between stakeholders guarantee long-term protection of these essential ecosystems against threats like drought and invasive species.

Migratory Bird Preservation

As a site of international importance recognized by multiple conservation organizations, the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge stands as an essential sanctuary for over 280 bird species along their migratory routes.

You’ll find this 79,570-acre refuge serves as a critical oasis in Nevada’s high desert, where migratory patterns bring more than a quarter million waterfowl and 20,000 water birds during peak seasons.

The diverse landscape includes freshwater marshes, alkali playas, and desert shrublands, supporting both spring and fall migrations of snow geese, tundra swans, and greater sage grouse. Notable bird species include golden-cheeked warblers, buffleheads, and various duck species.

The refuge’s viewing platforms and auto tours let you observe these magnificent birds while maintaining safe distances that protect their natural behaviors.

Architectural Remnants Through Time

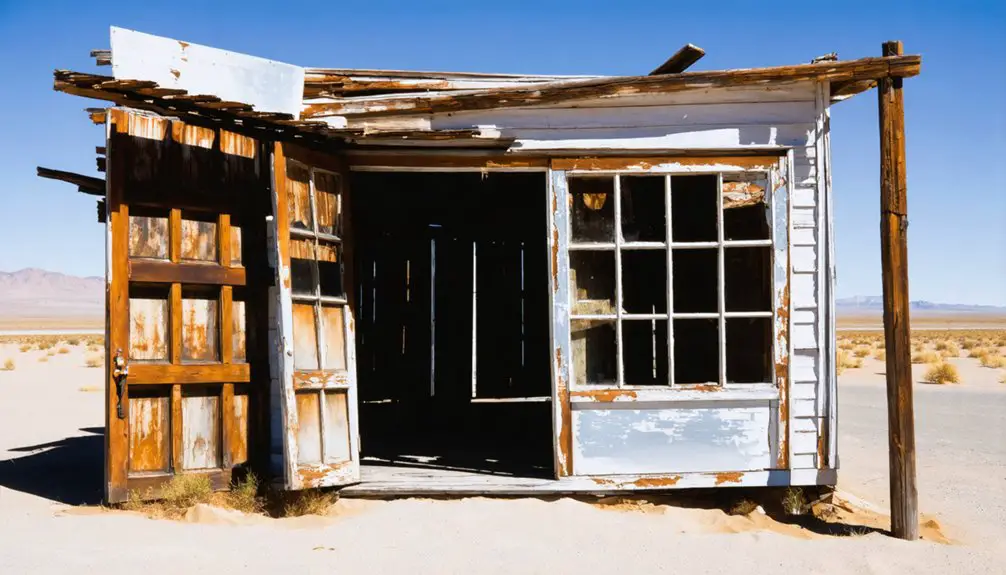

The architectural legacy of Stillwater, Nevada emerges through a diverse collection of remnants spanning different construction eras and building styles.

Among these remnants, the haunting presence of abandoned buildings in Seven Troughs reveals stories of a once-thriving mining community. Each dilapidated structure stands as a testament to the harsh conditions faced by its inhabitants, inviting exploration and reflection. Surrounded by the arid landscape, these sites serve as poignant reminders of the past and the impermanence of human endeavor.

You’ll find evidence of architectural evolution in the shift from early wooden structures, like the 1869 courthouse and Sanford Hotel, to later brick buildings that appeared by 1907. The town’s structural decay became pronounced after losing its county seat status in 1904.

You can still trace the community’s development through surviving elements: stone foundations in the Mountain Well Mining District, remnants of irrigation ditches, and fence lines that once defined residential plots.

The mining district’s secretive practices left concealed shafts and adobe ruins, while the townsite’s wooden buildings have largely deteriorated, leaving behind skeletal frames that tell stories of Stillwater’s bustling past.

From Bustling Hub to Abandoned Township

Founded in 1862 as a stage station, Stillwater rapidly evolved into Churchill County’s administrative heart, with its population reaching 150 by the time it secured county seat status in 1868.

You’ll find that early settlers, displacing Paiute traditions, transformed the marshy landscape through agricultural innovations like advanced irrigation systems. The town flourished with hotels, stores, and saloons serving the community’s growing needs.

However, Stillwater’s prominence wouldn’t last. The 1904 relocation of the county seat to Fallon triggered a devastating exodus, shrinking the population to just three dozen residents.

Despite a brief revival during the 1919-1921 geothermal exploration period, the town’s decline continued. By the mid-20th century, the once-bustling hub had transformed into a ghost town, with its legacy preserved within the Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge.

Historic Transportation and Mail Routes

Through pioneering trails blazed by Captain James H. Simpson in 1859, Stillwater became an essential waypoint along the Central Nevada Route.

You’ll find the historic path of the Pony Express running through this corridor from 1860 to 1861, establishing a significant 10-day mail delivery service between Missouri and California.

The area’s transportation evolution included the notable Stillwater Dogleg, which connected important mail stations across Churchill County.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Paranormal Activities or Ghost Stories Are Associated With Stillwater’s Abandoned Buildings?

You’ll discover over 50% of ghost sightings involve armed figures at windows. Reports include haunted locations with moving objects, unexplained EVP recordings, cold spots, and spirits of miners near abandoned structures.

How Accessible Is Stillwater by Car Today for Ghost Town Explorers?

You’ll need a high-clearance vehicle to navigate unpaved roads, especially during wet conditions. Check road conditions before traveling, bring emergency supplies, and consider using 4WD for the safest exploration access.

Are There Any Remaining Original Artifacts That Visitors Can See?

Peering through preserved passages, you’ll discover authentic artifacts within original buildings, including jail cells with ball and chain, mining equipment, antique scales, and historic graffiti scattered throughout accessible ruins.

What Caused the Devastating Fires That Damaged Parts of Stillwater?

You’ll find the fire origins primarily stemmed from wooden construction materials, stoves, lanterns, and human activities, though exact causes aren’t documented. These blazes caused devastating community impact in 1866 and 1873.

Which Famous Historical Figures Visited or Stayed in Stillwater During Its Peak?

You’ll find famous visitors like Pony Express rider William “Billy” Richardson, entrepreneur Charles Kent, and W.W. Wheeler graced this locale of historical significance during its prominent county seat and geyser-boom periods.

References

- https://www.destination4x4.com/stillwater-nevada-churchill-county-ghost-town/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Stillwater

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stillwater

- https://www.nvexpeditions.com/churchill/stillwater.php

- https://nevadamagazine.com/issue/january-february-2019/8096/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paiute_War

- https://wams.nyhistory.org/expansions-and-inequalities/westward-expansion/sarah-winnemucca/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Paiute_people

- https://utahindians.org/archives/paiutes/history.html

- https://www.rsic.org/225/History