You’ll find the ghost town of Sulphur, Nevada where miners extracted valuable sulfur deposits from 1869 through the 1980s. The town boomed after the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, which transported heavy mining equipment and ore. At its peak, crews of 17 men produced 6 tons of sulfur daily for shipment to San Francisco. While the Western Pacific line remains, abandoned mine shafts and processing facilities tell a deeper story of this once-thriving mining settlement.

Key Takeaways

- Sulphur, Nevada became a ghost town after its peak mining operations ended, which produced up to 150 tons of sulfur monthly.

- The mining district covered 1,000 acres and employed quarrying and room-and-pillar methods before its eventual abandonment in the 1980s.

- The town’s significance began in 1876 when Theodore Hale’s operation produced a 700-pound sulfur block showcased at the Centennial Exposition.

- Mining operations started with borax in 1856, transitioned to sulfur by 1865, and later focused on mercury production until 1957.

- Despite having the Western Pacific railroad line nearby, the town couldn’t sustain its population after mining operations ceased.

The Discovery of Sulfur Deposits (1869)

Three major developments in 1869 set the stage for sulfur mining in Nevada: the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, the establishment of key mining districts, and the introduction of essential smelting technology.

You’ll find that sulfur formations were commonly discovered alongside valuable silver-lead ores in districts like Eureka and Pioche. These deposits formed within Paleozoic sedimentary rocks, creating complex mineral combinations of galena, cerussite, and anglesite. Just like in the Comstock Lode discovery, the finding of these deposits brought waves of prospectors to the area.

Mining technology of the time struggled with these sulfur-rich ores until smelters arrived. The Trinity district’s Oreana smelter, built in 1867, proved that processing such complex ores was possible, leading to wider smelter adoption by 1869. Square set timbering became essential for safely extracting sulfur deposits while preventing mine collapse.

With the railroad’s completion, you could finally transport heavy mining equipment to these remote locations, making large-scale sulfur and metal extraction commercially viable.

Life in a Mining Boomtown

If you’d lived in Sulphur during its mining heyday, you’d have witnessed miners working punishing shifts in dangerous conditions, battling sulfur fumes and the constant threat of cave-ins while using basic hand tools and early processing equipment.

A dayshift of 17 men worked tirelessly to produce approximately 6 tons of sulphur each day for shipment to San Francisco markets.

The mine’s high-grade ore yielded an impressive 9.38 pounds of mercury per ton during its productive years.

The town’s social life centered around makeshift gathering spots like saloons and boarding houses, where miners sought relief from their grueling work days despite the limited amenities and poor sanitation.

Your survival would have depended on adapting to the harsh desert environment and volatile boom-and-bust economy, where premium prices for basic goods and unreliable infrastructure made daily life a constant challenge.

Daily Mine Worker Routines

Life in Sulphur’s mining boomtown revolved around grueling daily routines that began at sunrise and often stretched 10-12 hours.

Chinese workers made up a significant workforce, with over 218 laborers documented in the 1880 census.

You’d start your shift maneuvering treacherous underground tunnels or working the open-pit mines, where worker fatigue quickly set in from the physical demands of breaking ore and hauling materials.

Your tools were basic – picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows dominated the work until mechanization arrived.

The early 1900s brought limited diversity to mining operations when crews extracted small amounts of silver, potash, and mercury.

Mining hazards lurked everywhere, from toxic mercury fumes to the constant threat of tunnel collapse.

You’d take brief breaks in makeshift camps or sparse break huts, barely enough time to eat before returning to the demanding labor.

After work, you’d return to simple wooden shacks or tents, where basic amenities were scarce.

The nearby railroad’s arrival in 1911 finally improved supply access and transport options.

Community and Social Activities

When the day’s mining work ended, Sulphur’s social scene came alive in the town’s network of gathering spots. The company-built saloons served as hubs for card games, billiards, and community gatherings where miners exchanged news over drinks.

You’d find social cohesion developing through baseball games, dances, and outdoor activities that took advantage of the rugged landscape. The miners worked together extracting valuable sulfur and mercury from the area’s rich deposits.

Despite the mainly male population, families participated in community-organized picnics and seasonal celebrations. The post office connected residents to the outside world, while traveling performers occasionally brought entertainment to boost spirits.

Churches and meeting halls hosted religious services and social events. Though isolation and harsh conditions challenged the townspeople, their shared dependence on mining fostered strong bonds through mutual aid societies and cooperative daily life. With a population of 62 in 1920, the tight-knit community maintained close relationships despite their remote location.

Living Through Harsh Conditions

Operating a thriving sulfur mining town in Nevada’s unforgiving Black Rock Desert presented extraordinary challenges for Sulphur’s residents.

You’d face harsh living conditions daily, from blistering heat to bitter cold nights at 4,600 feet elevation. Your primitive home, likely a cramped hillside hut with a 5’4″ ceiling built from railroad ties, offered little protection from dust storms and extreme temperatures.

Survival strategies became essential as you’d work 12-hour shifts in toxic conditions, battling sulfur fumes with minimal safety measures.

You’d haul water from distant sources while dealing with unreliable supply routes along washboarded roads. Before 1911’s Western Pacific Railroad arrival, you’d transport sulfur 35 miles to the nearest rail line.

Medical care remained scarce, leaving you vulnerable to occupational hazards, accidents, and disease outbreaks.

Mining Operations and Production

Mining at Sulphur Bank launched in 1856 with borax extraction before expanding into sulfur mining by 1865. The California Borax Company operated the site until they discovered their sulfur ore was mixed with cinnabar, leading to a shift in focus.

By the 1870s, you’d find both underground tunnels and open-pit operations extracting valuable minerals.

Mercury production dominated from 1873 to 1957, with the site becoming a vital supplier during both World Wars.

You’d see impressive infrastructure, including a two-pit retort built in 1941 and a 15-ton furnace added in 1943. The operation was substantial, producing about 150 tons of sulfur monthly at its peak, with a workforce of 25 people.

The mining district spanned 1,000 acres, using both quarrying and room-and-pillar methods to extract its valuable resources.

Transportation and Railroad Connections

The Western Pacific Railroad‘s arrival in 1909 transformed Sulphur into an essential transportation hub for Nevada’s mining operations. Located at mile post 474.52, between Ronda and Floka stations, Sulphur’s railroad significance became evident as the town shipped up to 12 tons of sulfur daily by the 1920s. Local well driller C. L. Rowley helped establish critical water infrastructure for the railroad’s operations in 1910.

The transportation impact was profound, as you’ll find the railroad handled massive sulfur blocks weighing up to 700 pounds, connecting the town to important markets like Humboldt House on the Central Pacific line. Early production began in 1869 for sulfur before the railroad’s arrival, showing the area’s long mining history.

The railway’s infrastructure supported both outbound mineral shipments and inbound supplies, sustaining the community until the 1950s. While the town eventually succumbed to abandonment by the 1980s, you can still spot the active Western Pacific line running through this historic ghost town site today.

Notable Historical Events and Figures

You’ll find one of Nevada’s earliest recorded mining murders at Sulphur’s camp, where in 1875 J.W. Rover killed mine supervisor I.N. Sharp, leading to Rover’s distinction as Washoe County’s first legal execution.

Theodore Hale, who acquired half interest in the mine that same year, helped establish the town’s prominence by showcasing a massive 700-pound sulfur block at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

Hale’s leadership transformed the operation into a substantial producer, yielding about 11,000 pounds of sulfur daily by the late 19th century.

Murder at Mining Camp

Violence and lawlessness plagued Nevada’s early mining camps, with Pioche emerging as one of the deadliest settlements of the era. Before recording its first natural death, Pioche witnessed 72 killings, cementing its reputation in ghost town legends and mining camp violence.

You’ll find that saloons and gambling dens were hotspots for deadly confrontations, with murders occurring almost weekly in some camps. Notable victims included George Brown, murdered at Gravelly Ford, and prospectors Peter Lassen and Edward Clapper, killed near Clapper Creek in 1859.

These deaths highlighted the dangers of Nevada’s anarchic mining communities. The constant bloodshed attracted outlaws and claim jumpers while deterring legitimate investors like Mrs. Louisa M. Ellis, who withdrew her interests due to the volatile environment.

The First Legal Execution

While frontier justice often meant swift vigilante action, Nevada Territory’s first legal execution took place on January 9, 1863, when authorities hanged Allen Milstead outside Dayton for murdering Lyon County Commissioner T. Varney.

You’ll find that early executions drew massive crowds, with nearly 700 people witnessing Milstead’s hanging.

Before Nevada became a territory, capital punishment fell under Utah Territory’s jurisdiction. The region’s first documented execution occurred when officials hanged John Carr in 1860 for shooting Bernhard Cherry in Carson City.

As mining towns like Sulphur emerged, hangings typically happened at county seats until 1903, when executions moved to Nevada State Prison in Carson City.

Hale’s Centennial Sulfur Block

As Nevada’s frontier justice system evolved, the region’s sulfur mining industry was making its own mark on history.

In 1876, Theodore Hale’s legacy reached new heights when his mining operation extracted an extraordinary 700-pound block of pure sulfur from the Inferno mine site.

You’ll appreciate the sulfur significance of this massive specimen, which Hale proudly showcased at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition that same year.

The block wasn’t just a representation of Nevada’s mineral wealth – it demonstrated the territory’s industrial capabilities to the entire nation.

While Hale’s daily operation produced an impressive 11,000 pounds of sulfur for railroad transport, this singular block became a symbol of achievement.

The exhibit helped establish Nevada’s reputation as a serious player in America’s growing sulfur trade.

The Blue Flames Phenomenon

Numerous sulfur vents beneath volcanic craters create one of nature’s most spectacular phenomena – electric blue flames that illuminate the darkness.

You’ll find these mesmerizing blue flames when sulfur gas ignites upon contact with oxygen, reaching temperatures up to 600°C. The sulfur combustion creates an otherworldly display that’s only visible at night, appearing as rivers of electric blue fire against the dark volcanic rock.

While Indonesia’s Kawah Ijen volcano offers the most famous example, similar occurrences exist in Ethiopia’s Dallol region.

If you’re planning to witness this phenomenon, you’ll need protective gear – the burning sulfur releases toxic gases and acid droplets that can cause respiratory issues and skin irritation.

Local sulfur miners work alongside these blue flames nightly, braving harsh conditions to extract solidified sulfuric rock.

Decline and Abandonment

Despite its early promise as a mining hub, Sulphur’s isolation in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert ultimately sealed its fate.

The town’s economic challenges began as sulphur deposits, first claimed in 1875, became increasingly difficult to extract profitably. You’d have found the harsh environment and limited water sources made sustaining a community nearly impossible.

Population shifts accelerated when the mining industry declined, and the town’s reliance on the Western Pacific Railroad proved insufficient to maintain its viability.

The post office’s sporadic operation from 1899 to 1953 reflected the town’s unstable foundation. As businesses closed and services dwindled, residents abandoned their homes for more prosperous locations.

Today, the area’s restricted access and connection to the defunct Hycroft Mine stand as reminders of Sulphur’s bygone era.

What Remains Today

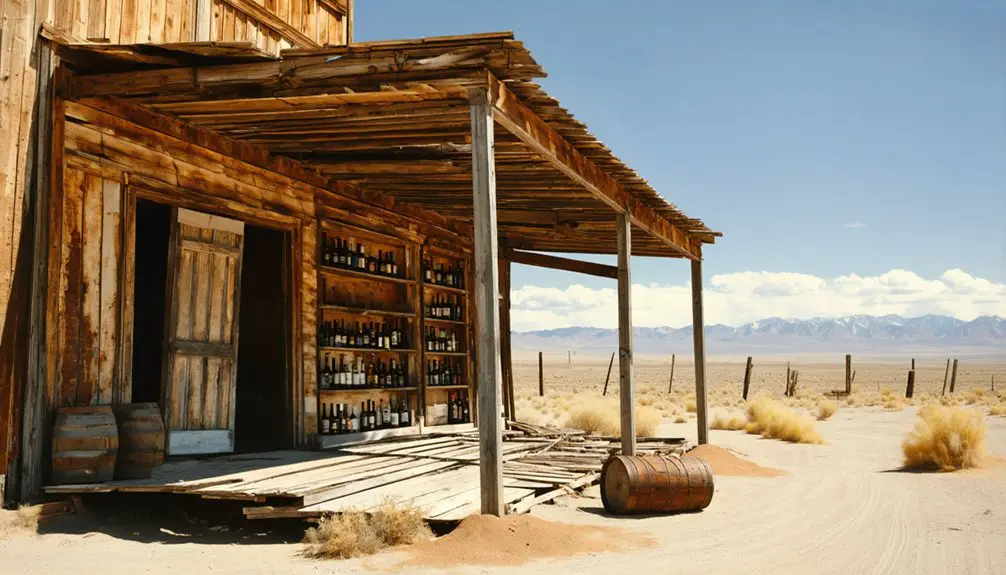

The remnants of Sulphur stand as weathered witnesses to its mining past. Today, you’ll find several collapsed buildings scattered across the site, with some structural remnants still identifiable despite their deteriorating condition.

Archaeological findings include an old cabin, a shot-up stove, and small huts built into hillsides – one particularly constructed from repurposed railroad ties. The site features a root cellar and various artifacts like bed springs, washing machine parts, and mining debris.

You can access these ruins via rough roads from Gerlach or Winnemucca, though they’re washboarded and challenging. While the massive Hycroft Mine now dominates the landscape, you’ll discover these ghost town remnants on National Conservation Lands.

exploring the history of treasure city reveals fascinating stories of the miners who once called this place home. As you delve deeper, remnants of old structures and artifacts provide a glimpse into the challenges they faced. The area’s unique blend of nature and history makes it a captivating destination for adventurers and history buffs alike.

However, there’s no formal parking or amenities, and access to the active mine operations remains restricted.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Average Population of Sulphur During Its Peak Years?

You’d find around 200-300 residents during peak mining operations in the early 1900s through 1920s, before the town’s decline led to complete abandonment by the 1950s.

Were There Any Schools or Churches Established in the Town?

Despite operating a post office for over 50 years, you won’t find any record of schools or churches in town. Mining operations and railway activities dominated, leaving no evidence of educational or religious institutions.

How Did Residents Handle Water Supply in This Desert Environment?

You’d rely on scarce springs and groundwater, while mining techniques demanded increasing water usage. Early settlers developed basic water conservation methods, importing supplies via railroad when local sources proved insufficient.

What Was the Average Wage for Miners Working in Sulphur?

Time is money, and while exact figures aren’t documented, you’d find wage fluctuations matched mining conditions in the early 1900s, likely ranging between $2-4 daily based on broader Nevada mining patterns.

Did Any Significant Natural Disasters Affect the Town’s Development?

You won’t find evidence of natural disasters affecting the town’s development. Historical records show economic and industrial factors, along with harsh desert conditions, shaped the area’s progression rather than catastrophic events.

References

- https://nevadamagazine.com/issue/january-february-2016/3009/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Sulphur

- https://wiki.blackrockdesert.org/wiki/Sulphur_Mining_District

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sulphur

- http://www.rimworld.com/brx/sulphur/sulphur.html

- https://ronhess.info/docs/report7_history.pdf

- https://nbmg.unr.edu/scienceeducation/ScienceOfTheComstock/Tour-Mining.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver_mining_in_Nevada

- http://www.miningartifacts.org/Nevada-Mines.html

- https://nevadamining.org/new-history-page/