You’ll find Taft, Montana’s most notorious ghost town, along the Montana-Idaho border where it earned the nickname “The Wickedest City in America.” This railroad boomtown exploded from zero to 7,000 residents between 1907-1910, boasting 35 saloons and a murder rate higher than Chicago’s. Built for the Milwaukee Road’s ambitious tunnel project, Taft met its end in the Great Fire of 1910, leaving behind a complex legacy of engineering feats, lawlessness, and untold stories beneath the forest floor.

Key Takeaways

- Taft, Montana was a railroad boomtown established in 1907 that grew to 7,000 residents before becoming a ghost town.

- Known as “The Wickedest City in America,” Taft had 35 saloons, rampant crime, and minimal law enforcement.

- The Great Fire of 1910 destroyed the entire town, marking the beginning of its decline into abandonment.

- Archaeological excavations have uncovered thousands of artifacts revealing the town’s original layout and daily life.

- Visitors can access the ghost town site near Interstate 90’s exit 5, following the original Milwaukee Road railway grade.

The Birth of a Boomtown

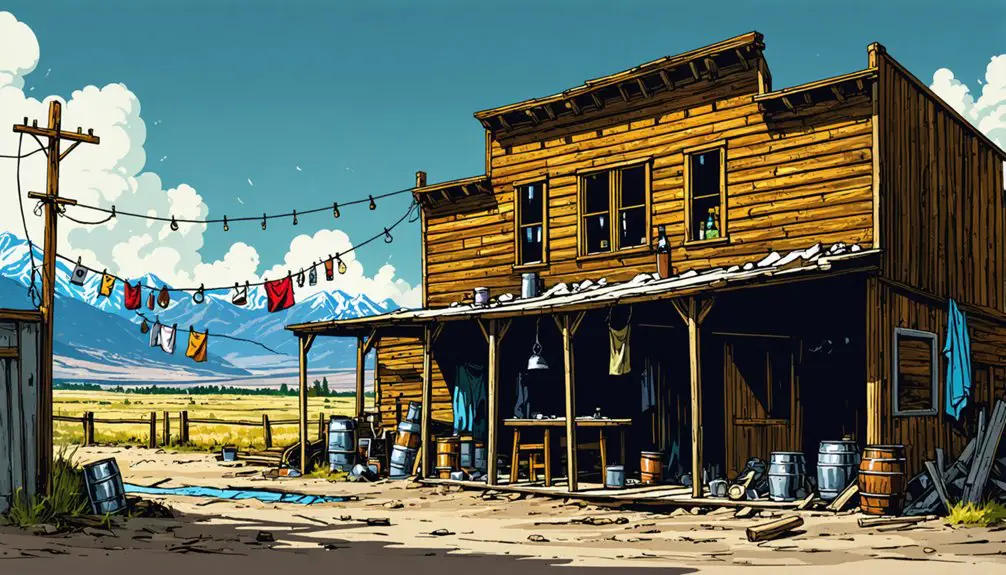

While the Milwaukee Road railroad pushed westward in 1907, it established the rough-and-tumble town of Taft, Montana as a staging ground for one of its most ambitious projects – the 1.7-mile Taft Tunnel through the Bitterroot Mountains.

You’d have witnessed an explosive growth as the population surged from zero to nearly 3,000 residents by 1910, briefly reaching 7,000 at its peak.

The town’s transient economy revolved entirely around the tunnel’s construction, with an immigrant workforce flooding in from around the world. These laborers earned between $1.80 and $3.50 daily for dangerous work as drillers, teamsters, miners, and support staff.

The Northern Pacific Railroad extension supplied the burgeoning boomtown, while Milwaukee Road’s strategy involved rapidly creating and abandoning such settlements as construction projects demanded.

Life in “The Wickedest City in America”

In Taft’s heyday, you’d find a staggering 35 saloons and 27 bars packed with railroad workers, miners, and loggers letting loose after grueling shifts.

With virtually no law enforcement presence, the town’s 7,000-10,000 inhabitants engaged freely in gambling, drinking, and frequent brawls that earned Taft its reputation as “The Wickedest City in America.”

The murder rate surpassed Chicago’s, while roughly 500 prostitutes worked the streets of this lawless frontier outpost where violence and vice ruled the day.

Saloons and Wild Nights

During its heyday, Taft, Montana earned its reputation as “The Wickedest City in America” through an astounding concentration of vice – most prominently its 35 saloons serving a largely transient population of railroad workers.

The saloon culture defined the town’s character, with drinking establishments packed shoulder-to-shoulder along muddy streets.

You’d find workers from across the globe gathering in these bustling halls, where gambling, drinking, and entertainment ruled the night.

Different ethnic groups often claimed their own corners of the nightlife entertainment scene, though the shared pursuit of pleasure united them all.

With no churches or schools to temper the revelry, Taft’s saloons became the beating heart of social life.

Even after fires periodically ravaged the wooden structures, the town would rebuild its drinking establishments with remarkable persistence.

Law Enforcement Gone Missing

As Taft’s population swelled with railroad workers and opportunists, the town’s single deputy sheriff proved woefully inadequate to maintain order in what would become known as “The Wickedest City in America.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find effective law enforcement, with the nearest real police presence stationed over 100 miles away in Missoula.

Law enforcement challenges mounted as ethnic tensions erupted between immigrant groups, particularly Albanians and Montenegrins. The murder rate surpassed both Chicago and New York combined, with 17 bodies discovered in spring 1909 alone.

Community resistance to authority, combined with language barriers and cultural clashes, made solving crimes nearly impossible. Forest Service rangers held jurisdiction but lacked real power, while county officials rarely ventured into this lawless frontier. Like the weak law enforcement that plagued Montana’s early mining camps in the 1860s, Taft’s lack of proper policing created an environment ripe for criminal activity.

Instead, personal vendettas and vigilante justice filled the void where law enforcement should have been.

Daily Violence and Gambling

The lawless atmosphere in Taft bred a culture of violence and vice that would make even the toughest frontier towns look tame by comparison.

Within the town’s 27 saloons, you’d find gambling tables packed with railroad workers betting their hard-earned wages, while violent encounters erupted regularly between ethnic groups and rival laborers.

Gambling disputes, fueled by heavy drinking and a volatile mix of nationalities, often ended in bloodshed. The murder rate soared past Chicago’s, making Taft’s reputation as “The Wickedest City in America” well-earned.

The Northern Pacific Railroad actually encouraged this gambling culture, seeing it as a way to keep workers distracted from competing railroad projects.

With roughly five prostitutes for every man and no churches or schools in sight, Taft existed purely as a haven for vice and lawlessness.

Ethnic Communities and Social Dynamics

Life in Taft embodied the complex social fabric of America’s western frontier, where diverse ethnic communities converged amid the town’s railroad and timber industries.

You’d find Swedes working alongside Italians, Chinese laborers next to Australians, and Montenegrins sharing space with French-Canadians. This ethnic diversity created both opportunities and challenges, as language barriers and cultural differences often led to tension. Like the nomadic tribal peoples before them, many workers moved with the seasons and available work.

The Montenegrin community showcased remarkable social cohesion under their leader known as “The King,” whose murder sparked a blood oath and violent reprisals.

When he died, nearly 1,000 men joined his funeral procession, demonstrating the strength of ethnic bonds. While some groups maintained tight-knit communities, others lived as transients – disappointed miners, gamblers, and college men seeking their fortunes in this rugged Montana outpost.

Wild West Justice and Lawlessness

If you’d visited Taft during its peak, you wouldn’t have found many lawmen patrolling its dangerous streets, as the town’s reputation for violence kept most officers away.

With just one deputy sheriff stationed in town and the county sheriff 100 miles away in Missoula, maintaining order proved nearly impossible in this isolated frontier community.

The lack of law enforcement presence allowed violence to flourish, resulting in a murder rate that surpassed those of Chicago and New York combined.

Lawmen Feared Taft’s Violence

During Taft’s lawless heyday, even hardened lawmen feared entering the remote Montana boomtown, where a single part-time deputy struggled against rampant violence that produced more murders than Chicago and New York combined.

You’ll understand lawmen’s fears when you consider that in spring 1909 alone, 17 bodies emerged from melting snow, each bearing knife or gun wounds.

Violence escalation reached shocking levels, with 18 documented homicides in 1907 – none solved. The county sheriff, stationed 100 miles away in Missoula, couldn’t maintain order.

Even Forest Service rangers proved powerless against the town’s widespread vice, which included 500 prostitutes and countless saloons.

Cultural conflicts between immigrant groups, particularly Montenegrins and Albanians, often ended in deadly gunfights rather than legal resolution.

Sheriff Deputies Rarely Patrolled

Rarely did law enforcement venture into Taft’s dangerous streets, where a single part-time deputy served as the town’s token authority figure.

You’d find the nearest sheriff stationed 100 miles away in Missoula, leaving Taft’s residents largely to fend for themselves. Deputy morale remained low, as one officer couldn’t possibly maintain order in a town where murders outpaced those of Chicago and New York combined.

The sheriff challenges were overwhelming – with widespread prostitution, gambling, and frequent killings going unchecked.

When violence erupted between ethnic groups like Albanians and Montenegrins, or when bodies were discovered on the outskirts of town, law enforcement’s response was often delayed or nonexistent.

Even Forest Service rangers found themselves powerless to control the rampant lawlessness that defined Taft’s wild character.

Railroad Legacy and Engineering Feats

While other railroads had already established routes through Montana, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad took on one of North America’s most ambitious engineering challenges.

You’ll find their crowning achievement in the St. Paul Tunnel near Taft – a 1.66-mile bore through solid mountain that showcased remarkable construction innovations.

Engineering crews started digging from both Montana and Idaho, meeting underground with less than 3/8 inch misalignment at 8,771 feet deep. The work proved brutal, claiming 72 lives among the 8,000-strong international workforce.

You can still see evidence of their advanced techniques in the massive steel viaducts and tight mountain curves.

The tunnel’s electrification and precision engineering set new standards for early 1900s railroad construction, leaving a lasting legacy in American rail history.

Daily Life in a Temporary Town

As railroad construction boomed in early 1900s Taft, you’d find a bustling but lawless atmosphere where thousands of immigrant laborers crowded into hastily built wooden structures. Life revolved around grueling 24-hour work shifts, with laborers sharing beds in crowded boarding houses as day and night crews swapped places.

The town’s transient lifestyles blurred traditional social hierarchies, mixing college-educated men with lumberjacks and former miners in the same saloons. You’d encounter a diverse mix of Swedes, Italians, Chinese, and other immigrants seeking fortune.

With 27 saloons, gambling dens, and brothels dominating the social scene, violence was common. The nearest sheriff was in Missoula, leaving Taft fundamentally lawless.

Disease spread quickly through the cramped quarters, while dangerous working conditions and alcohol-fueled conflicts contributed to numerous deaths.

The Great Fire’s Devastating Impact

When the Great Fire of 1910 struck Taft during the driest year on record, it transformed the wild railroad town into an apocalyptic inferno.

Nature’s fury transformed the untamed railroad outpost of Taft into a hellscape during the devastating Great Fire of 1910.

You’d have witnessed trees exploding like giant torches and hurricane-force winds hurling burning debris across half-mile canyons. The devastating blaze was part of an unprecedented series of fires that burned over 3 million acres across the region. The town’s lack of community resilience became evident as many residents chose drinking over fighting the flames, while forest rangers struggled to organize any meaningful fire suppression efforts.

As the inferno bore down, you would’ve seen panicked townspeople scrambling to escape by train while burning embers rained from above.

The town’s destruction was swift and complete – not a single structure remained standing. Only one resident died directly from the flames, though the fire’s legacy would reshape American forestry policies for generations to come.

Uncovering Lost Stories

Through urban archaeology and research, you’ll discover forgotten histories of immigrant laborers who carved railroads through mountains, and the violent clashes that erupted from cultural tensions and booze-fueled disputes.

In Comet City’s own turbulent past, hardworking miners earned a daily wage of $3 to $3.50 while facing dangerous working conditions.

You can trace the town’s dark legacy through artifacts that reveal a place where 27 saloons operated alongside hundreds of prostitutes, where one deputy sheriff struggled to maintain order in a town deadlier than Chicago and New York combined.

The tale of “The King,” the murdered Montenegrin leader, and his killer’s subsequent death exemplifies the lawless nature of this railroad boomtown, where language barriers, gambling debts, and jealousies often ended in bloodshed.

Modern Archaeological Discoveries

You’ll find the recently rediscovered Taft Cemetery holds crucial clues about the railroad laborers and diverse ethnic groups who built this boomtown, though the 1910 Big Burn destroyed many wooden grave markers.

The archaeological teams have mapped thousands of artifacts using specialized software and metal detectors, revealing the town’s original layout and social structure through items like British teacups and railroad-era tools.

Working through layers of history, archaeologists have identified at least six possible graves and uncovered evidence of the town’s notorious reputation through discoveries of bullets and weapons that support accounts of violence and lawlessness.

Cemetery Excavation Findings

Modern archaeological discoveries at Taft Cemetery began in 2018 after retired miner Butch Jacobson helped pinpoint its long-forgotten location.

Using high-tech metal detectors, archaeologists from the University of Montana and Forest Service have identified roughly 40 possible grave sites through careful archaeological methodology.

You’ll find evidence of the cemetery’s historic significance through:

- Metal artifacts including belt buckles, uniform buttons, and bullet casings that tell tales of the transcontinental railroad era

- A British teacup fragment from 1902-1907, discovered by an 8-year-old explorer

- Non-native iris flowers marking potential Greek Orthodox graves where headstones are absent

While grave site identification continues seasonally, the team’s using non-invasive techniques like forensic canines to map the cemetery without disturbing these historic resting places.

Railroad Camp Artifact Recovery

Alongside ongoing cemetery investigations, extensive artifact recovery efforts at Taft’s railroad camp site have revealed rich details about life during the town’s peak construction years.

You’ll find evidence of the camp’s diverse workforce through personal belongings that tell stories of Swedish, Italian, Chinese, and other immigrant laborers who shaped this frontier outpost.

The artifact significance extends beyond basic construction tools, painting a vivid picture of daily life.

Archaeologists have uncovered remnants of saloons, brothels, and communal living spaces that highlight the town’s wild character.

Labor history comes alive through medical artifacts from the camp hospital, documenting the dangerous conditions workers faced while drilling the 1.77-mile tunnel.

These discoveries showcase how Taft’s residents lived, worked, and survived in this challenging mountain environment.

From Railroad Hub to Bicycle Trail

Though the Milwaukee Road’s tracks no longer carry freight through Montana’s Bitterroot Mountains, the historic Taft Tunnel has found new life as part of the Route of the Hiawatha Trail.

This remarkable transformation from railroad innovation to recreational destination showcases community resilience, preserving an essential piece of American engineering history.

Today, you’ll find thousands of cyclists riding through the same 1.7-mile tunnel where immigrant workers once labored.

The trail offers:

- Access to one of North America’s most precise tunnel engineering feats

- Views of historic railroad infrastructure, including the fallen substation

- Connection between Montana and Idaho along the original Milwaukee Road grade

You can access this repurposed marvel near Interstate 90’s exit 5, where a Montana Department of Transportation maintenance yard marks the trail’s entrance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous Outlaws Known to Have Visited or Lived in Taft?

You won’t find records of infamous criminals or outlaw visits here – the town’s violence came from local ethnic groups, railroad workers, and labor disputes rather than legendary Western outlaws.

What Happened to the Railroad Workers After the Town Was Destroyed?

You’ll find the railroad legacy scattered as workers migrated to other rail projects and mining towns across Montana and nearby states, with skilled engineers relocating their families while laborers sought fresh opportunities.

Did Any Ghost Stories or Supernatural Legends Emerge From Taft’s History?

You’ll find a thousand whispers of haunted locations, but surprisingly few documented ghost sightings exist. The blood oath murders and mysterious disappearances of Montenegrins sparked supernatural legends that still intrigue visitors today.

How Did Women Besides Prostitutes Fare in the Male-Dominated Boomtown?

You’d find women’s roles severely limited beyond prostitution, with few jobs, no social support networks, and constant danger. The harsh social dynamics left non-prostitute women isolated, vulnerable, and largely invisible in historical records.

What Native American Tribes Lived in the Area Before Taft’s Establishment?

You’ll find the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreille were the primary Native tribes in western Montana’s mountains, while the Crow and Blackfeet influenced nearby regions with their rich cultural traditions.

References

- https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2020/jan/19/idaho-miner-helps-rediscover-lawless-bitterroot-bo/

- https://www.explorebigsky.com/a-name-without-a-place/33494

- https://nbcmontana.com/news/montana-moment/taft-last-boom-town-of-the-american-west-was-lawless-and-industrious

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PqUq1lSGw5I

- https://www.traillink.com/historic-places/the-railroad-ghost-town-of-taft/

- https://www.cdm.me/english/the-story-of-taft-in-montana/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taft

- https://vp-mi.com/news/2022/nov/30/author-details-tafts-wicked-history-new-book/

- https://whitefishpilot.com/news/2024/apr/10/talk-looks-at-vanished-montana-town-that-was-once-/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montana_Vigilantes