Terra Cotta was a short-lived industrial settlement northwest of Lake Elsinore, founded in 1887 after John D. Huff discovered coal and clay deposits. Despite $50,000 in initial investment, the town struggled with poor resource quality and transportation challenges. A devastating factory fire in 1891 accelerated its decline, though brief revivals occurred until 1912. Today, you’ll find only dirt roads and faint building outlines where this ambitious manufacturing center once stood. Its forgotten story reveals California’s diverse boom-bust cycle beyond gold mining.

Key Takeaways

- Terra Cotta City, established in 1887 near Lake Elsinore, was founded on dreams of profitable clay and coal deposits.

- The town’s economic viability collapsed after factory fires in 1891 and permanent closure by spring 1892.

- Transportation challenges and substandard mineral resources prevented Terra Cotta from becoming the industrial center its founders envisioned.

- A brief revival occurred when California Fireproof Construction Company operated a pipe factory from 1906-1912.

- Today, only foundations and faint outlines remain beneath sagebrush, with no standing structures left at the site.

The Birth of a Clay Town: Discovery and Early Settlement (1885-1887)

In 1885, a pivotal discovery by John D. Huff transformed the remote Warm Springs Valley northwest of Lake Elsinore. Huff identified valuable coal and clay deposits that promised industrial potential in this undeveloped region. Despite early challenges of limited infrastructure, the discovery quickly attracted interest.

The untapped riches of Warm Springs Valley awaited until Huff’s keen eye revealed its industrial destiny.

By May 1887, the Southern California Coal and Clay Company was incorporated to mine these resources and manufacture terra cotta, pipes, and brick. The company’s formation catalyzed rapid development, with Terra Cotta City being laid out and subdivided by summer 1887.

Construction of a factory began immediately, establishing the foundation for new community dynamics. As workers and families settled in the newly platted town, a sense of optimism prevailed. By the end of 1887, investors had committed over $50,000 in development of the town’s infrastructure and mining operations.

The population grew around the promise of employment, with residents establishing the essential social structures needed for their fledgling community. Similar to Calico’s silver mining history, Terra Cotta’s development was driven by the extraction of resources that were in high demand at the time.

Mining Dreams: Coal and Clay Deposits That Promised Prosperity

Despite the initial enthusiasm surrounding Terra Cotta’s mineral resources, the coal and clay deposits that fueled the town’s founding proved disappointing soon after extraction began.

The coal’s low grade failed to attract major industrial buyers, while the clay couldn’t meet manufacturing standards necessary for profitable production. These material deficiencies crushed early mining aspirations.

Transportation obstacles further compounded these economic challenges. Without the planned railroad—deemed too costly to build—Terra Cotta’s products traveled by wagon to Elsinore, drastically reducing their competitiveness in regional markets.

The isolation hampered investment potential and limited growth opportunities.

When the Terra Cotta factory burned down in October 1891, it represented the culmination of the area’s struggles.

Though rebuilt by February 1892, operations ceased permanently that spring, marking the end of Terra Cotta’s first industrial chapter.

Building an Industrial Hub: Factory Development and Production

Terra Cotta’s industrial backbone emerged when the Southern California Coal and Clay Company constructed its factory in 1887, establishing specialized kilns and equipment for ceramic pipe and brick production.

You’ll find evidence of the factory’s resilience in its rapid rebuilding after the devastating 1891 fire, with operations resuming by February 1892 despite significant setbacks.

The industrial footprint expanded in 1906 when California Fireproof Construction Company developed a new plant featuring four coal-fired kilns specifically designed for ceramic pipe manufacturing, representing the town’s second wave of industrial development. The factory incorporated iron rods to reinforce their architectural terracotta elements, improving structural stability in their building materials. Similar to this development, Los Angeles Pressed Brick Company had already established an impressive factory complex that included four kilns and two smoke stacks by 1890.

Factory Infrastructure

When the Southern California Coal and Clay Company established Terra Cotta City in 1887, they quickly initiated the development of industrial infrastructure designed to capitalize on the area’s abundant mineral resources.

The factory design included facilities for manufacturing pipes, bricks, and terra cotta products, reflecting the company’s ambitions despite limited transportation options.

Without affordable railway access, the operation relied on wagon transportation to deliver products to Elsinore. This logistical challenge, combined with disappointing clay and coal quality, severely hampered production efficiency. The factory likely used the stiff-mud method for brick production, a technique that was being introduced to California operations between 1885-1890.

The manufacturing process would have required careful selection of clay and proper firing in kilns to achieve products that wouldn’t crack or flake when exposed to the elements, a critical consideration for the company’s architectural terracotta offerings.

The factory’s industrial legacy was further complicated by a devastating fire in October 1891. Though rebuilt by February 1892, operations ceased permanently that spring.

Later revival attempts occurred with the California Fireproof Construction Company’s pipe factory (1906-1912), marking the final chapter in Terra Cotta’s industrial story.

Clay Product Manufacturing

Although the Southern California Coal and Clay Company initially established Terra Cotta City with ambitious industrial goals, the region’s true manufacturing legacy emerged through its diverse clay product operations.

You’d find factories producing an impressive array of fired ceramic goods: bricks, roofing tiles, sewer pipes, and architectural terra cotta.

The manufacturing techniques varied by product complexity. Terra cotta required skilled artisans who understood clay aesthetics and behavior, with production taking about seven days for standard items before mechanization.

Clay preparation involved soaking and manual kneading to maintain proper plasticity. Craftsmen employed traditional methods similar to those used by early American tile manufacturers like the Zoar community. The four kilns and drying facilities documented in the 1890 factory complex formed the industrial heart of production. The unique geological profile of Alberhill provided both sedimentary and metamorphic clays ideal for various ceramic applications.

Companies like Pacific Clay Products and Los Angeles Pressed Brick developed these operations into diversified industrial hubs that sustained Terra Cotta’s economy for decades.

Transportation Woes: The Failed Railroad and Wagon Transport Challenges

Despite initial plans for connecting Terra Cotta to the regional rail network, the failed railroad construction became one of the most significant factors in the town’s eventual demise.

You would’ve witnessed ceramic products transported solely by wagon for nearly a decade after the town’s 1887 founding, creating severe transportation challenges. Wagons had to travel six miles through Lake Elsinore to reach La Laguna’s rail station, traversing rough terrain that damaged fragile products. This situation mirrored early California mining communities that relied on freight wagons over rugged roads before rail infrastructure. The poor transportation infrastructure reflected challenges similar to Sacramento, which had its own flooding issues from Sutter Lake before the railroad development.

This isolation crippled Terra Cotta’s economic impact while other Southern California towns flourished with rail connections. The high costs of wagon transport slashed profits, discouraged investment, and limited market reach.

When a rail spur finally reached nearby Alberhill in 1896, it came too late—Terra Cotta’s operations ceased entirely by 1912.

The Great Factory Fire of 1891 and Its Aftermath

The devastating fire that erupted in October 1891 at the Southern California Coal and Clay Company factory marked a critical turning point in Terra Cotta’s brief history. When a night watchman’s lantern ignited the facility, it completely destroyed the town’s industrial heart.

A careless lantern sparked the inferno that would ultimately seal Terra Cotta’s industrial fate.

Despite remarkable community resilience—rebuilding the factory by February 1892—the recovery proved short-lived. By spring 1892, operations ceased entirely, triggering severe economic decline. Workers and families departed, seeking opportunities elsewhere as Terra Cotta faded into obscurity.

Brief revival attempts occurred after 1896 with the nearby Alberhill railroad spur, and later between 1906-1912 when California Fireproof Construction Company operated a pipe factory.

After 1912, industrial activity ended permanently. Today, only a namesake road remains of what was once a hopeful industrial settlement.

Resource Reality: When Poor Quality Clay Undermined a Town’s Future

While Terra Cotta’s founders initially envisioned a thriving industrial center built around local natural resources, the fundamental quality of these materials ultimately doomed the settlement’s prospects.

Despite substantial investment exceeding $50,000, both coal and clay deposits proved substandard compared to superior materials in nearby Alberhill.

This resource management failure compounded when expensive railroad connections never materialized. You can imagine the frustration as operators faced wagon transportation to Elsinore, greatly increasing costs and destroying economic sustainability.

Operations continued intermittently, but profitability remained elusive.

Brief Revival: The Alberhill Railroad Connection and New Hope

The railroad spur’s completion in 1896 connected Alberhill to the California Southern Railroad, creating economic optimism and reducing the isolation that had previously hindered growth.

Between 1906 and 1912, you’ll find that Alberhill experienced a modest industrial resurgence as the 7.7-mile rail line facilitated the movement of clay, coal, and finished terra cotta products to wider markets.

This revival peaked during the Fireproof Construction Company’s operations, which capitalized on rail connectivity to transport materials for the region’s expanding fireproof building market.

Railroad Spur Creates Hope

In 1896, following years of logistical challenges that hampered Terra Cotta’s industrial potential, a vital railroad spur line was constructed to connect the struggling mining town with the California Southern Railroad‘s main line.

This infrastructure improvement revolutionized mining logistics by eliminating the six-mile wagon journey previously required to reach railheads.

The railroad impact extended beyond Terra Cotta, ultimately connecting to the Alberhill mining district where superior clay deposits were being discovered.

This transportation network provided essential support for both areas, enabling efficient shipment of coal and clay to broader markets via the La Laguna station near Lake Elsinore.

The spur line later proved instrumental during Terra Cotta’s brief revival (1906-1912) when the California Fireproof Construction Company established a ceramic pipe factory, temporarily restoring industrial activity to the area before its final decline.

Industrial Resurgence 1906-1912

Despite Terra Cotta’s history of industrial struggles, the town experienced a remarkable resurgence between 1906 and 1912 when the California Fireproof Construction Company established operations in the area.

This revival transformed the settlement’s economic impact through specialized pipe manufacturing that met growing regional construction demands.

The newly constructed railroad spur to Alberhill proved essential, eliminating costly wagon transportation to Elsinore and integrating Terra Cotta into the regional industrial network.

This infrastructure improvement reduced shipping costs and expanded market accessibility for the fireproof construction materials.

The company’s operations represented a strategic shift from raw material extraction to value-added manufacturing, positioning Terra Cotta within Southern California’s building supply chain.

Though short-lived, this twelve-year period of sustained industrial activity constitutes a significant chapter in Terra Cotta’s industrial legacy before its eventual decline into ghost town status.

Fireproof Construction Company Era

Although Terra Cotta’s industrial prospects had dimmed by the late nineteenth century, a transformative development in 1896 breathed new life into the struggling settlement. The construction of a railroad spur connecting Terra Cotta to Alberhill eliminated the logistical challenges that had plagued earlier operations, creating a viable industrial network.

This critical infrastructure improvement attracted the California Fireproof Construction Company, which established pipe manufacturing operations between 1906 and 1912.

You’ll find that the company capitalized on growing demand for fireproof materials following major urban fires across North America. The enterprise represented a strategic shift from general terra cotta products to specialized fireproofing applications.

The rail connection integrated Terra Cotta with the broader Alberhill mining district, creating an industrial legacy that would define this brief but significant revival period.

Final Industrial Gasps: California Fireproof Construction Company (1906-1912)

The final chapter in Terra Cotta’s industrial story began when the California Fireproof Construction Company established operations in 1906. Following several failed ventures in the area, including the Southern California Coal and Clay Company (1887-1892), this pipe manufacturing operation represented Terra Cotta’s last gasp of industrial relevance.

You’d find the company utilizing local clay deposits—despite their historically poor quality—to produce pipes for regional construction needs. Despite improved railroad access via the Alberhill spur built in 1896, persistent economic challenges prevented long-term sustainability.

The company operated for just six years before closing in 1912, effectively ending Terra Cotta’s industrial legacy. No significant expansion or diversification occurred during this period, and after the factory’s closure, Terra Cotta faded into obscurity, with minimal physical remnants of its industrial past.

What Remains Today: Traces of Terra Cotta in the Modern Landscape

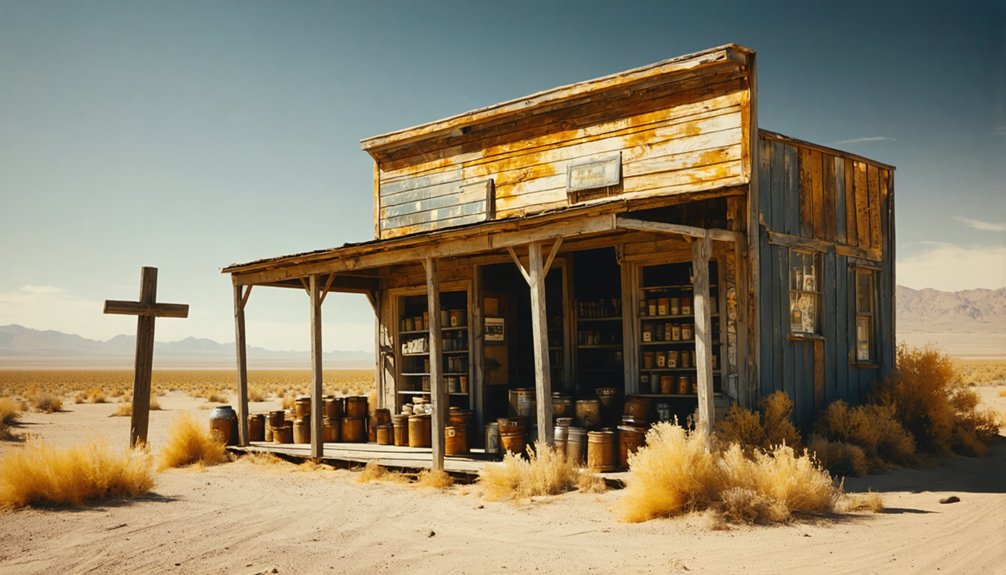

If you visit Terra Cotta today, you’ll find only a grid of dirt streets cutting through sagebrush where this once-bustling industrial town stood.

No original buildings remain standing, with the town’s physical legacy reduced to these faint outlines visible in the open scrubland northwest of Lake Elsinore.

You can access these sparse remnants via Terra Cotta Road from Lakeshore Drive or Nichols Road from I-15, though you’ll encounter no interpretive signage or tourism infrastructure at this ghost town site.

Tremont House history and significance is often overshadowed by other landmarks, yet it played a pivotal role in the development of the region. Not only did it serve as a social hub, but it also reflected the architectural trends of its time, drawing visitors from far and wide. Exploring its remnants can provide a unique glimpse into the past and the stories that shaped the area.

Physical Remnants Today

Visitors traveling through the seemingly unremarkable landscape northwest of Lake Elsinore might easily overlook the vanished industrial community of Terra Cotta.

Today, you’ll find no standing structures in this ghost town—only foundations and faint outlines of former buildings beneath encroaching sagebrush. The old street grid remains barely visible through desert vegetation, while the kiln sites that once produced ceramic pipes have been reduced to ground-level remnants.

You can access the site via Lakeshore Drive by Terra Cotta Road or Nichols Road from I-15, but don’t expect historical markers or visitor facilities.

The abandoned clay mines that operated until 1940 are now just terrain depressions and spoil piles. With the railway spur long gone and mining equipment vanished, Terra Cotta exists primarily as archaeological curiosity rather than tourist destination.

Finding Terra Cotta

Located approximately five miles northwest of Lake Elsinore in Riverside County, Terra Cotta exists today as little more than a name on regional maps and scattered physical remnants across an undeveloped landscape.

If you’re interested in ghost town exploration, Terra Cotta presents a challenge as it lacks official markers, designated trails, or public access points.

To locate this site of historical significance, you’ll need to:

- Follow Terra Cotta Road, the only modern reference to the town’s existence

- Research historical archives and mining records before your visit

- Respect private property boundaries, as many remnants lie on undeveloped private land

Unlike more developed ghost towns, Terra Cotta’s story is preserved primarily through written accounts and digital archives rather than preserved structures or interpretive displays.

Terra Cotta’s Place in California’s Ghost Town Heritage

While many California ghost towns emerged from gold and silver rushes, Terra Cotta stands distinct as an industrial ghost town born from manufacturing ambitions rather than precious metal extraction.

It exemplifies a broader pattern of late 19th-century industrial settlements that rose swiftly and declined rapidly due to resource and infrastructure challenges.

Unlike famous ghost town legends tied to gold bonanzas, Terra Cotta’s story revolves around failed industrial ambitions in clay and coal manufacturing.

Its trajectory mirrors contemporaries like Calico and Bodie, though with manufacturing rather than mining at its core.

Terra Cotta’s brief existence—from its 1887 founding through its brief 1906-1912 revival—adds important dimension to California’s ghost town heritage, demonstrating that the boom-bust cycle affected diverse economic ventures beyond precious metals extraction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Notable Residents or Characters in Terra Cotta’s History?

Beyond John D. Huff, Terra Cotta’s founder, you’ll find few notable figures in historical anecdotes. The anonymous night watchman responsible for the 1891 factory fire represents the sparse documented personalities.

What Daily Life Amenities Existed for Terra Cotta Residents?

You’d find minimal amenities in Terra Cotta’s daily life. Residents accessed only basic housing, a company store, communal water source, and relied on Elsinore for essential services beyond industrial necessities.

Did Terra Cotta Experience Any Natural Disasters Besides the Factory Fire?

Yes, Terra Cotta faced significant flood risks from the Mojave River, particularly during the 1938 regional floods. Earthquakes’ impact on the abandoned settlement included structural damage from seismic events like the 1992 Landers earthquake.

Were There Any Schools, Churches, or Community Buildings in Terra Cotta?

By coincidence, Terra Cotta’s school history and church significance remain undocumented. You won’t find records of educational institutions, religious buildings, or community structures in this primarily industrial settlement.

What Happened to Displaced Residents After Terra Cotta’s Final Abandonment?

You’ll find displacement effects poorly documented in historical records. Resident relocation patterns suggest dispersal to nearby Elsinore or Alberhill communities where mining and railway operations offered alternative employment opportunities.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OD9M6MP6RRU

- https://beyond.nvexpeditions.com/california/riverside/terracotta.php

- https://www.latimes.com/la-trw-sclandmarks-pg-photogallery.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/environmental-analysis/documents/ser/townsites-a11y.pdf

- https://www.sfgate.com/travel/article/calico-ghost-town-knotts-berry-farm-17643437.php

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terra_Cotta

- https://www.camp-california.com/california-ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4abnhupnLac

- https://dornsife.usc.edu/magazine/echoes-in-the-dust/