You’ll find Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico, as a near-ghost town of 350 residents, where abandoned historic structures stand alongside functioning buildings like the 1917 courthouse. Originally named for its yellow clay deposits by Spanish settlers, this 1832 Mexican land grant territory became entangled in complex ownership disputes after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The town’s rich layers of Native American, Hispanic, and Anglo-American history unfold through its weathered buildings and cultural landmarks.

Key Takeaways

- Tierra Amarilla has declined to 350 residents, approaching ghost town status while maintaining active government buildings and community spaces.

- Many historic structures have been abandoned since 1959, showcasing gradual decay and the town’s transition towards partial abandonment.

- The town retains its courthouse as Rio Arriba County’s seat, preventing complete desertion despite significant population decline.

- Original buildings from the 1832 Mexican land grant era face weathering effects from high-altitude exposure.

- Despite near ghost town conditions, the community preserves its cultural heritage through occupied historic buildings and traditional Hispanic practices.

The Legacy of Yellow Earth: Origins and Native Heritage

While the name Tierra Amarilla simply means “yellow earth” in Spanish, this region’s identity stems from distinctive yellow clay deposits along the Chama River Valley that indigenous peoples utilized for thousands of years.

You’ll find evidence of continuous human presence stretching back 5,000 years, with ancient pueblo sites south of Abiquiu revealing the deep roots of ancestral Puebloan culture.

The area served as a crucial hub where Pueblo, Navajo, Ute, and Jicarilla Apache peoples engaged in trade and cultural exchange across the Four Corners region. In recent times, the Jicarilla Apache have become the largest landowners within the grant area.

Their indigenous practices, including the use of yellow clay for pottery and ceremonial purposes, reflected a profound connection to the land.

This rich Native heritage persisted until the mid-1800s, when shifting political tides began disrupting traditional communal land use patterns. The Mexican government later established the Tierra Amarilla Land Grant, encompassing 600,000 acres of this historically significant territory.

Land Grant Saga: From Mexican Territory to American Southwest

When the Mexican government established the Tierra Amarilla Land Grant in 1832, they couldn’t have foreseen how this community-focused settlement would become a flashpoint for cultural conflict and legal battles.

Mexico’s 1832 Tierra Amarilla settlement started as a harmonious community but transformed into a battleground of cultures and legal strife.

You’ll find the roots of conflict trace back to 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo transferred New Mexico to U.S. control.

By 1860, the U.S. government had dramatically altered the grant’s nature, reclassifying it from communal to private ownership under Francisco Martinez.

This transformation sparked decades of legal disputes as Anglo speculators, led by Thomas Catron, consolidated vast tracts of land.

The change stripped Hispanic settlers of their traditional common-use rights, fundamentally altering their way of life.

As land passed to Midwestern developers, the original inhabitants found themselves increasingly marginalized, setting the stage for future conflicts.

By 1880, the landscape changed dramatically when Thomas Catron sold portions of the land to the Denver and Rio Grande Railway.

Cultural Crossroads: Hispanic Settlers and Indigenous Peoples

The cultural landscape of Tierra Amarilla had long been shaped by the Ute, Navajo, and Jicarilla Apache tribes before permanent Hispanic settlement began.

You’ll find a story of indigenous resistance as these tribes fought to maintain their ancestral hunting grounds against increasing settler pressure in the 1860s.

The cultural exchange between Hispanic settlers from Abiquiu and indigenous peoples created a complex dynamic of conflict and coexistence.

- Ute warriors conducting raids to protect their territories

- Apache hunters following seasonal migration patterns

- Hispanic farmers tending communal lands and small family plots

- Indigenous bands staging strategic resistance from mountain camps

The Santa Fe Ring’s Impact on Local Communities

In late nineteenth-century New Mexico, a powerful coalition known as the Santa Fe Ring orchestrated one of the territory’s largest land grabs, fundamentally reshaping Tierra Amarilla’s social fabric.

Through legal manipulation and political corruption, Ring members like Thomas B. Catron gained control of up to 80% of land grant properties, targeting communal lands that had sustained local Hispanic communities for generations. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo protections were largely ignored during this period of exploitation.

You’ll find that this systematic land dispossession forced many settlers into wage labor or migration, as they lost access to traditional grazing and farming lands. The U.S. courts favored Anglo-American legal practices over traditional Hispanic land ownership customs, making it nearly impossible for original grant holders to defend their claims.

Despite these challenges, community resilience emerged through sustained resistance. Local families fought to preserve their cultural heritage and land rights, though they often lacked resources to challenge the Ring’s well-connected lawyers.

These conflicts would continue shaping Tierra Amarilla’s story well into the twentieth century.

The 1967 Courthouse Uprising and Its Lasting Effects

Tensions erupted into violence on June 5, 1967, when activist Reies López Tijerina led members of the Alianza Federal de Mercedes in a raid on the Tierra Amarilla courthouse. The uprising’s impact reverberated through New Mexico as raiders sought to free detained Alianza members and arrest District Attorney Alfonso Sanchez over land grant disputes.

You can picture the dramatic scene that unfolded:

- Two officers shot and wounded during the confrontation

- Hostages taken, including a reporter and deputy sheriff

- National Guard troops, tanks, and artillery deployed across the county

- The state’s largest manhunt ensuing in the days after

The courthouse raid catalyzed Chicano activism throughout the Southwest, transforming quiet resistance into bold action. His actions helped shift the Mexican American community from being perceived as a sleeping giant to an awakened force for change. The organization maintained strong community engagement through continued support from local activists and residents.

While Tijerina served two years in prison, his defiant stand against systemic land grant injustices inspired a generation of Latino civil rights leaders.

Modern Day Remnants of a Historic Settlement

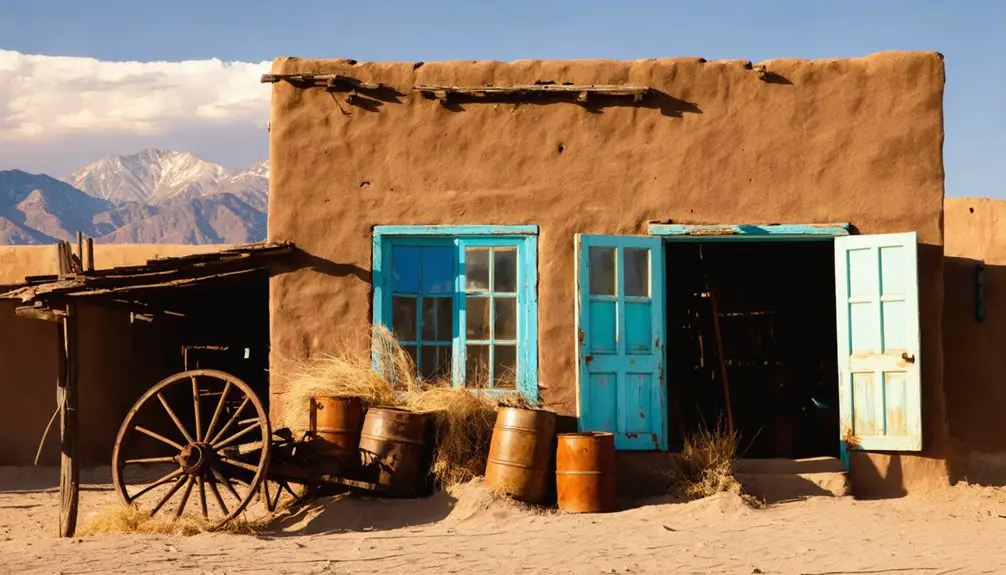

You’ll find a striking juxtaposition in today’s Tierra Amarilla, where abandoned historic structures like Tio’s Ballroom stand alongside the still-functioning Rio Arriba County Courthouse.

While historic markers throughout the town document its rich past as part of the 1832 Tierra Amarilla Land Grant, many original buildings now show the weathering effects of high-altitude exposure and time. Situated at over 7000 feet, the town experiences dramatic seasonal temperature variations that have contributed to its weathered appearance.

Like many of New Mexico’s ghost town sites, visitors are reminded to leave artifacts undisturbed to preserve the area’s history for future generations.

The town’s remaining occupied buildings, including the courthouse and local businesses, maintain a thread of continuity with the past while serving the area’s small but resilient population.

Abandoned Buildings Stand Silent

Today, dozens of abandoned buildings stand as silent sentinels across Tierra Amarilla’s landscape, their concrete and adobe walls weathering under the New Mexican sun.

These military remnants from the 1950s Air Force Station tell a story of Cold War vigilance and community life, now frozen in time.

You’ll find an abandoned architecture that includes:

- Decaying radar stations that once housed cutting-edge AN/FPS surveillance equipment

- A 1953 gymnasium where service members maintained their physical readiness

- Former family trailer sites where military households made their homes

- Weather-beaten barracks that sheltered those who kept watch over American skies

Though listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 2001, these structures continue their slow dance with decay, largely untouched since their abandonment in 1959.

The 767th Aircraft Control Squadron operated from this location during its active years, serving as a crucial defense post during the Korean War era.

Historic Markers Tell Stories

Standing as silent storytellers along Tierra Amarilla’s roads and historic sites, weathered markers chronicle the settlement’s complex history from its 1832 Mexican land grant origins through centuries of cultural transformation.

You’ll find references to early struggles, as raids from Utes, Navajos, and Jicarilla Apaches delayed settlement until the 1860s.

The marker significance extends beyond mere historical facts, preserving community memory of pivotal moments – from the Spanish Trail used by friars in 1776 to the 1967 land rights conflicts led by Reies Tijerina.

At 7,860 feet elevation, these markers reveal Tierra Amarilla’s strategic position in the Chama River Valley, where Native, Spanish, and Anglo influences converged.

They’re enduring symbols to 5,000 years of regional habitation and ongoing struggles for cultural identity and land rights.

Cultural Heritage Lives On

Though nearly two centuries have passed since its 1832 Mexican land grant origins, Tierra Amarilla’s cultural heritage endures through its historic structures, activist legacy, and tight-knit Hispanic community.

You’ll find remarkable cultural resilience in this town of 350 residents, where heritage preservation remains essential through:

- The 1917 courthouse that still serves as Rio Arriba County’s seat

- Active community spaces like the local café and post office that maintain social connections

- Painted messages and slogans that commemorate the 1967 courthouse raid and land rights movement

- Traditional Hispanic customs, language, and communal practices passed down from original land grant settlers

Despite its near ghost town status, Tierra Amarilla’s identity stays strong through its people, who continue fighting for land rights while preserving their ancestral traditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Restaurants or Lodging Options Still Exist in Tierra Amarilla Today?

You’ll find local dining at Margarita’s Comedor & Lounge, TA Lobo Cafe, and Cafe Comedor y Margaritas, but you won’t discover formal rustic accommodations – you’ll need lodging in nearby towns.

Are There Guided Tours Available of the Historic Courthouse Site?

Like discovering an old time capsule, you’ll find guided tour options available through bus tours and museum programs that explore the historic courthouse’s dramatic 1967 raid and land grant movement history.

What Is the Current Population of Tierra Amarilla?

You’ll find the current demographics show approximately 637 residents as of 2023, though there’s some variation in estimates. The historically significant town has experienced a steady population decline recently.

Can Visitors Access Any Preserved Buildings From the Original Settlement?

While you’ll find preserved structures of historical significance, most are restricted. You can view the courthouse and ballrooms from outside, but you’ll need special permission for interior access.

What Seasonal Events or Festivals Are Still Celebrated in Tierra Amarilla?

You’ll find traditional seasonal celebrations including Catholic feast days, Dia de los Muertos, and harvest fiestas, plus intimate community gatherings like the Good Medicine Confluence and local church-based cultural events.

References

- http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/history/usa/nm/tierra-amarilla.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tierra_Amarilla

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tierra_Amarilla_Land_Grant

- https://www.newmexico.org/places-to-visit/regions/northcentral/tierra-amarilla/

- http://www.ghosttowns.com/states/nm/tierraamarilla.html

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Tierra_Amarilla

- https://time.com/archive/6635594/new-mexico-the-agony-of-7-erra-amarilla/

- https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2547&context=nmhr

- https://escholarship.org/content/qt1ww5q38d/qt1ww5q38d.pdf

- https://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/downloads/28/28_p0091_p0092.pdf