You’ll find Tono’s remains about 20 miles south of Olympia, where this once-thriving coal mining town housed over 1,000 residents at its 1920s peak. Founded in 1907 by Washington Union Coal Company, the community featured the world’s largest aerial tramway and essential services like a hospital and school. While diesel engines spelled Tono’s decline by 1932, its transformation from bustling company town to strip mine reveals fascinating layers of Pacific Northwest industrial heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Tono was a thriving coal mining town established in 1907 near Olympia, Washington, reaching a peak population of 1,000 residents.

- The town operated as a self-contained community with houses, hospital, school, and other essential services for mining families.

- Declining coal demand and switch to diesel locomotives in 1932 led to Tono’s gradual abandonment by the 1950s.

- Strip mining operations in 1967 by Pacific Power & Light Company destroyed most physical traces of the original town.

- The last residents left in 1976, and today only scattered foundations remain, with most artifacts preserved in local museums.

The Birth of a Mining Town

While many Western towns grew organically around trading posts or crossroads, Tono emerged with a singular purpose in 1907 when the Washington Union Coal Company established it as a company-owned mining settlement.

You’ll find this deliberate town planning reflected in its strategic location – about 20 miles south of Olympia in Thurston County, positioned at the end of a railroad spur to efficiently transport coal to Union Pacific’s hungry steam locomotives.

A Japanese railroad worker suggested the name “Tono” in 1909, which locals later connected to the phrase “ton of coal.” Interestingly, this was the same year that H.G. Wells published his novel titled “Tono”.

The mining techniques employed here served one master: the railroad’s endless appetite for fuel. The company built everything needed for a self-contained community, from housing to a hospital, creating a controlled but complete mining town. Today, Tono stands as a ghost town, with almost no traces of its once-bustling past remaining.

Life in Tono’s Golden Era

During Tono’s peak in the 1920s, over 1,000 residents called this company town home, living among 125 houses built specifically for the mining community.

You’d have found all your daily needs met within town limits – from medical care at the local hospital to shopping at the general store. Children attended the town school while their parents worked primarily in the mines or supported the community through essential services.

The town’s cultural fabric was woven with immigrant influences, including Japanese railroad workers who inspired the town’s name. Community events revolved around mining schedules, bringing together families in shared social activities. The town’s impressive industrial heritage included what was once the largest aerial tramway in the world. Like many settlements in the American West, the town’s fate was tied to natural resource booms that drove its economy.

The superintendent’s house stood apart from workers’ homes, reflecting the era’s social hierarchy, though everyone relied on the same company-provided amenities that kept this coal-focused town running.

A Community Built Around Coal

When the Washington Union Coal Company established Tono in 1907, they didn’t just build a mine – they created an entire community centered around coal production.

You’d have found over 1,000 residents living in 125 houses at its peak, with all the essentials of small-town life: a hospital, hotel, general store, and school. The community dynamics revolved entirely around the mining operations that powered Union Pacific’s steam locomotives.

The town’s economic sustainability depended on coal demand, and you can see how this shaped Tono’s destiny. Even its name, reportedly coined by a Japanese worker as a contraction of “ton of coal,” reflects the deep connection between community and industry.

The dedicated railroad spur that served the mines became the town’s lifeline to the outside world.

The Railroad’s Vital Connection

As the lifeblood of Tono’s coal operations, the railroad spur connected this remote mining town to Union Pacific’s broader network, enabling the daily transport of thousands of tons of coal to fuel steam locomotives across the region.

You’ll find railroad history woven into every aspect of Tono’s design. The Japanese railroad workers who helped build the spur in 1909 left their mark in the town’s very name. The Washington Union Coal Company operated the town’s mining operations, maintaining tight control over its workforce and infrastructure.

Japanese railroad workers shaped more than just tracks in Tono – their cultural legacy lives on in the town’s very identity.

Everything from the post office to the company store was strategically positioned near the tracks, creating an efficient hub for coal transportation. Today, visitors can explore these scenic routes while learning about the town’s rich history. The town’s infrastructure served a single purpose: keeping Union Pacific’s steam engines running.

When diesel locomotives arrived in the 1930s, they transformed railroad operations forever, severing Tono’s essential connection to the railroad network and setting the stage for its eventual decline.

Decline of the Company Town

The shift to diesel locomotives in 1932 delivered a crushing blow to Tono’s coal-dependent economy, triggering the town’s irreversible decline. Without economic resilience to weather this technological disruption, you’d have witnessed the town’s rapid unraveling as Union Pacific sold its mines to Bucoda Mining Company.

Much like how the Central Washington Railway transformed Govan in 1889, Tono’s fate was deeply tied to railroad operations. You can trace how quickly things fell apart – the population plummeted from over 1,000 in the 1920s to just a handful by 1950. Residents literally uprooted their homes, moving them to nearby towns as Tono’s community institutions shuttered one by one. Extensive strip mining operations further deteriorated the landscape, leaving much of the former town site permanently altered.

The Last Family Standing

You’ll find the last vestiges of Tono’s human presence in the story of John and Lempi Hirvela, who occupied the former mine superintendent’s house until 1976.

While most residents had long since departed, the Hirvelas maintained their home as the final inhabited structure in this once-bustling coal town.

Their property was eventually acquired by Pacific Power & Light during the strip mining expansion, marking the definitive end of residential life in Tono.

The Hirvela Legacy

Living on as the last full-time residents of Tono, John and Lempi Hirvela moved into the former mine superintendent’s home in 1923, where they’d remain until 1976.

You’ll find their resilience remarkable as they stayed through multiple ownership changes and the town’s steady decline, even after the 1932 shift from steam to diesel locomotives crushed the local coal industry.

The Hirvelas, with their four children, represented more than just residents – they became living symbols of Tono’s significance and transformation. At its peak in the 1920s, they were among over 1,000 residents who called this coal mining town home.

Their home served as the final stronghold of community life until Pacific Power & Light Company’s strip mining operations in the 1980s erased most physical traces of the town.

Today, their legacy helps you understand the human experience of early-mid 20th century mining communities in Washington state.

The area where their home once stood is now part of extensive reclamation projects aimed at restoring the natural environment.

Last Standing House

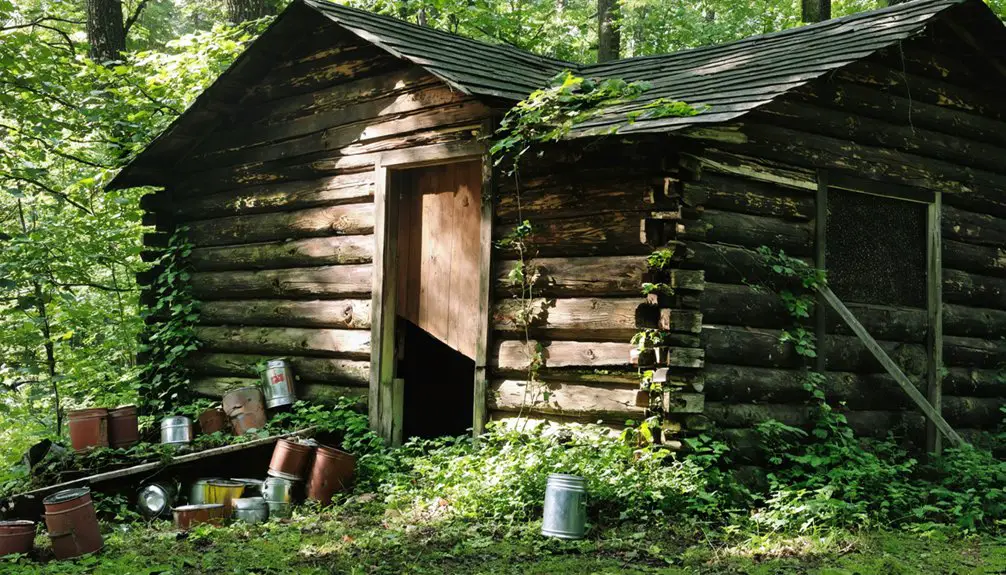

Standing as a monument to Tono’s endurance, the mine superintendent’s house remained the final residential holdout in this vanishing coal town until 1976.

As the last residence tied to Tono’s mining heritage, this company-owned property witnessed the town’s transformation from a bustling community to a ghost town.

- Located 20 miles south of Olympia, near Tenino and Bucoda

- Originally housed the mine superintendent, reflecting the social hierarchy of the company town

- Survived longer than other structures before Pacific Power & Light’s strip mining operations

- Represented one of the few physical remnants after most of Tono was cleared in the 1980s

- Stood as the final chapter of residential life in a town that began with the Washington Union Coal Company in 1907

Transformation Through Strip Mining

While Tono had already declined following the closure of its underground mines in the 1950s, the arrival of strip mining in 1967 permanently altered both the town’s remains and its surrounding landscape.

Pacific Power & Light Company began operations near the old townsite, extracting coal to fuel the nearby Centralia Power Plant. This new form of mining proved devastatingly efficient, removing massive layers of earth to access coal seams and, in the process, obliterating most traces of Tono’s existence.

The ecological impact was profound – where homes and community buildings once stood, you’ll now find only scattered foundations, pits, and ponds.

Some locals say the heart of old Tono lies beneath one of these ponds near the Centralia Steam Plant.

Legacy in Pacific Northwest History

Today, Tono’s legacy endures as more than just a vanished coal town beneath strip-mined earth.

You’ll find Tono’s significance woven into the fabric of Pacific Northwest industrial heritage, marking a pivotal change in mining technology and transportation.

- The town exemplified the classic company model, where Union Pacific Railroad created a self-sustaining community around coal extraction.

- You can trace the evolution of energy through Tono’s timeline, from steam locomotives to diesel engines.

- Local museums now showcase rescued artifacts like coal carts, preserving tangible connections to the past.

- The site demonstrates how resource-dependent communities adapted to changing economic landscapes.

- Tono’s transformation from underground to strip mining reflects broader shifts in industrial practices that shaped the region’s development.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Were the Average Wages for Coal Miners in Tono?

You’d see coal miners earning around $4.60 per day under the 1933 Appalachian Wage Agreement, though exact Tono wage comparisons aren’t documented. Mining conditions and union negotiations shaped local pay rates.

Were There Any Major Mining Accidents or Disasters in Tono’s History?

While mining safety records show one documented death in 1916 and a non-fatal tunnel collapse in 1956, you won’t find reports of major disasters at Tono like those at other Washington mines.

What Happened to the Cemetery After the Town Was Abandoned?

Like footprints in shifting sand, the cemetery’s fate remains shadowy. You won’t find much cemetery preservation evidence since Pacific Power’s 1980s strip mining likely erased any burial traces from Tono’s landscape.

Did Native American Tribes Have Any Historical Connection to the Tono Area?

Yes, the Nisqually Tribe historically occupied the region, maintaining deep connections through fishing and seasonal camps. You’ll find their ancestral territory encompassed Tono’s location within their broader traditional homeland.

How Deep Were the Original Underground Coal Mines at Tono?

You’ll find the original mine depth for coal extraction at these workings isn’t precisely documented, though regional mines reached 2,700 feet, and Tono’s technology suggests comparable depths.

References

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Tono

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tono

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Tono

- https://www.houseofhighways.com/usa/west/washington/tono

- https://olympiatime.com/2011/03/27/tono-washington/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPQCs-4Mb6E

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://stateofwatourism.com/ghost-towns-of-washington-state/

- https://www.wta.org/go-outside/seasonal-hikes/fall-destinations/hidden-history-ghost-town-hikes

- http://www.chronline.com/stories/coal-mining-had-long-history-in-hanaford-valley