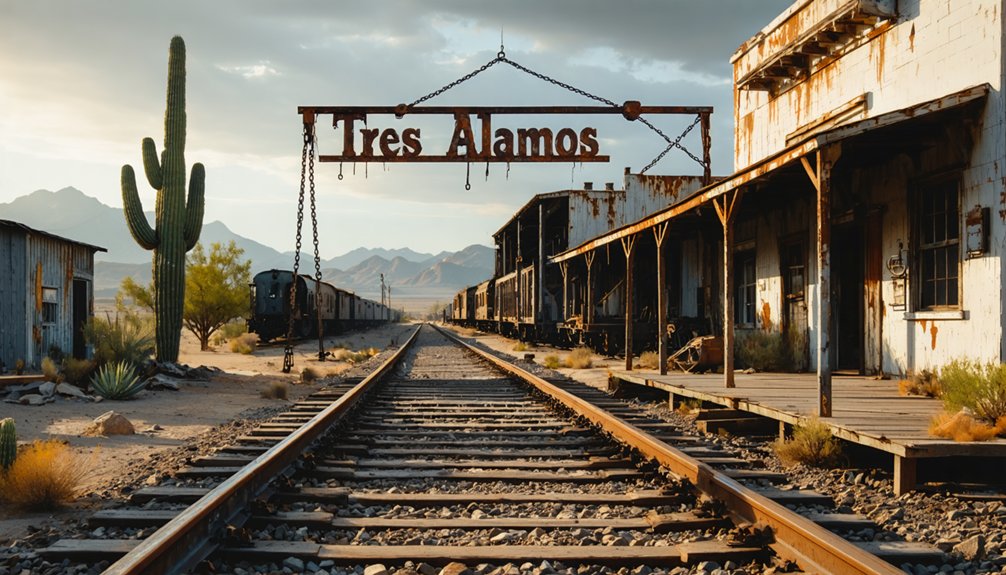

Established in 1874 along the San Pedro River, Tres Alamos thrived as an essential stagecoach stop and ranching center in Arizona Territory. You’ll find it served as a key postal hub connecting Tucson and Tombstone until the Southern Pacific Railroad’s 1881 arrival shifted transportation patterns. Today, no structures remain at this ghost town, only scattered foundation stones and building rubble accessible via rough roads requiring high-clearance vehicles. The site’s silent desert landscape tells countless frontier stories.

Key Takeaways

- Tres Alamos was established in 1874 along the San Pedro River, serving as a stagecoach stop between Tucson and Tombstone.

- The settlement declined after the Southern Pacific Railroad’s arrival in 1881 shifted transportation patterns away from stagecoach routes.

- No standing structures remain today, with only scattered foundation stones and building rubble marking the ghost town’s location.

- Visitors need high-clearance vehicles to access the remote site via rough unpaved roads with no facilities available.

- The town once thrived as a postal and transportation hub in a region threatened by Apache raids and outlaw activity.

Origins Along the San Pedro River (1874)

Three factors converged to establish the settlement of Tres Alamos along the west bank of the San Pedro River in 1874.

First, the fertile rift valley created ideal conditions for ranching operations stretching north toward what would later become Benson.

Second, growing transportation needs demanded connection points along established routes, with Pomerene Road serving as a significant link.

Third, scattered ranchers required postal services to maintain business and personal connections.

The post office became Tres Alamos’ central purpose, functioning as an essential communications hub for twelve years until 1886.

While modest in its offerings, this outpost provided crucial services to those seeking independence in Arizona Territory’s frontier.

The area was classified as a ghost town after no physical structures were left to mark its existence.

Unlike other settlements that would later benefit from railroads, Tres Alamos remained primarily focused on supporting local ranching communities.

Like nearby Fairbank, the area experienced significant flooding issues from the unpredictable San Pedro River that complicated permanent settlement.

Life in the Arizona Territory Frontier

While Tres Alamos took shape as a modest service center for local ranchers, the broader Arizona Territory frontier presented harsh realities for all who ventured there.

You’d have found yourself in a landscape where the mining boom attracted fortune seekers while cattle drives moved herds across virgin ranges. Daily life balanced opportunity with danger as Apache raids threatened settlements during the quarter-century of warfare. The Chiricahua Apache resistance under Chief Cochise was particularly fierce as they fought to protect their ancestral lands.

Three defining aspects of frontier life included:

Frontier existence demanded vigilance against outlaws, resilience through boom-bust cycles, and self-sufficiency beyond the reach of distant authority.

- Constant vigilance against outlaws and rustlers who operated freely near the Mexican border

- Economic volatility as boomtowns rose and fell with resource extraction fortunes

- Self-reliance in a region where law enforcement remained scarce and military protection centered around forts like Verde

Gun ports carved into cabin logs still testify to the tension permeating these frontier communities. Visitors can experience these harsh living conditions through living history tours that provide immersive glimpses into the challenges of Western frontier settlement.

The Sobaipuri Legacy and Cultural Crossroads

When you visit Tres Alamos today, you’re standing where Sobaipuri settlements once flourished along the San Pedro River before Apache raids and Spanish colonization displaced these native farmers in the 18th century.

The Sobaipuri people created a complex network of cultural exchange at this crossroads, adopting elements from neighboring Puebloan and O’odham groups while maintaining their distinct agricultural practices and social customs. Unlike the Seviper II who were primarily classified as riverine people, the Sobaipuri maintained greater mobility between settlements.

Their strategic river villages represented the northern frontier of Uto-Aztecan expansion, functioning as buffer communities between competing indigenous groups until warfare and disease dramatically altered the cultural landscape of southern Arizona. Archaeological evidence indicates the Sobaipuri were linguistically related to the O’odham peoples, sharing cultural roots that extend deep into the region’s past.

Native River Settlements

Before European settlers arrived in southern Arizona, the Sobaipuri people had established thriving communities along the San Pedro and Santa Cruz rivers, creating a cultural foundation that would later influence Tres Alamos.

These native inhabitants built extensive settlements on fertile riverbanks, where they practiced intensive agriculture year-round.

When you explore the area today, you’ll notice evidence of their sophisticated riverbank agriculture systems that once sustained large populations:

- Remnants of irrigation canals that diverted river water to cultivated fields

- Sites of mat-covered houses arranged in linear patterns along waterways

- Adobe structures including fortified enclosures that protected inhabitants from outside threats

The Sobaipuri’s agricultural expertise and strategic settlement patterns demonstrate their deep connection to this landscape—a connection that preceded Tres Alamos by centuries.

According to Mike Foster’s educational videos, the exact timeframe of habitation of the Sobaipuri in this region remains a subject of ongoing archaeological research.

The increasing Apache depredations eventually forced the Sobaipuri to merge with the Papago tribe, leading to their extinction as a distinct cultural group.

Warfare and Displacement

The Sobaipuri people, once thriving along the San Pedro River, found themselves caught in the crossfire of escalating conflicts between Spanish colonizers and Apache warriors throughout the 18th century.

Their villages, including Tres Alamos, served as essential buffer settlements protecting Spanish interests while absorbing the brunt of Apache raids.

Archaeological research has documented over 80 sites belonging to the Sobaipuri people throughout southern Arizona, revealing their extensive presence before displacement.

Father Kino introduced Spanish culture and ranching practices to the region in 1692, forever altering the traditional Sobaipuri way of life.

As you explore this ghostly landscape today, you’re walking ground where Sobaipuri resilience was ultimately overcome by relentless warfare, disease, and diminishing Spanish support.

By 1762, the remaining Sobaipuri abandoned the San Pedro Valley entirely, seeking refuge at Mission San Xavier del Bac.

Their displacement opened the region to Apache dominance, transforming Tres Alamos into contested territory marked by cycles of settlement and abandonment.

The strategic location that once made this site valuable ultimately sealed its fate as a crossroads of conflict.

Cultural Exchange Patterns

Standing at the confluence of diverse cultures, Tres Alamos embodies the complex interactions between indigenous traditions and European influences that shaped Arizona’s borderlands. The Sobaipuri, speaking a Piman language, established villages along riverways that became focal points for cultural blending when Father Kino arrived in 1691.

You’ll find evidence of indigenous adaptation throughout the region:

- Sobaipuri settlements incorporated Spanish mission structures while maintaining their cultural identity.

- Mixed naming patterns across landscapes reflect layered histories of O’odham, Spanish, and Euro-American presence.

- Village leadership actively facilitated European relationships while preserving indigenous social structures.

This cultural crossroads transformed Tres Alamos from a seasonal Sobaipuri settlement into a microcosm of the borderlands experience, where riparian corridors fostered not just agriculture but intercultural dialogue spanning four centuries.

Ranching Economy and Post Office Establishment

Rooted in Spanish mission communities and Mexican land grants from the 1680s, ranching gradually shaped the economic landscape of the Santa Cruz Valley, eventually extending to settlements like Tres Alamos.

You’ll find that large Hispanic families established permanent ranching operations through these land grants, creating a lasting ranching legacy in southern Arizona.

After Apache threats diminished and the Southern Pacific railroad arrived around 1881, Tres Alamos ranchers gained essential market access.

However, economic challenges soon followed as “use it or lose it” government policies encouraged overstocking. The Tres Alamos Association even advocated for herd size regulations by 1885.

The establishment of a post office signified Tres Alamos had achieved sufficient population and economic activity, providing isolated ranchers with fundamental connections to goods, services, and communication.

Stagecoach Routes and Transportation Hub

Positioned strategically along the San Pedro Valley, Tres Alamos emerged as a significant stagecoach stop on the route connecting Tucson and Tombstone before 1879.

Four-horse coaches and buckboards regularly traversed this essential transportation artery, carrying mail, passengers, and supplies throughout southeastern Arizona.

The stagecoach significance of Tres Alamos is evident in how it:

- Served as a critical relay point for mail and passenger services before railroad arrival

- Connected multiple transportation networks serving mining districts between Tucson, Tombstone, and Mesilla

- Functioned as a hub near important watering points on the San Pedro River

Transportation decline came swiftly in 1879 when faster routes bypassed Tres Alamos completely.

The Southern Pacific Railroad‘s arrival in Benson by 1880 sealed the town’s fate, causing stagecoach services to dwindle and eventually cease altogether.

The Railroad’s Impact and Economic Shift

When the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Tucson on March 17, 1880, it dramatically altered the economic landscape of southeastern Arizona. The railroad’s decision to cross the San Pedro River at Benson rather than Tres Alamos proved fatal for the once-thriving settlement.

Railroad expansion created new economic centers, with Benson quickly emerging as the “Hub City” where multiple rail lines converged by 1881. This transportation shift caused immediate economic disruption in Tres Alamos.

By February 1879, the well-regarded Tres Alamos House was already up for sale, anticipating the coming changes. You’d have witnessed stagecoach companies dropping Tres Alamos from their routes, followed by mail service transferring to Benson by September 1880.

As profitable mines in Tombstone and Bisbee directed their ore shipments to railroad junctions, Tres Alamos’ commercial infrastructure collapsed, bypassed by progress.

Why Tres Alamos Became a Ghost Town

When the Southern Pacific Railroad bypassed Tres Alamos in favor of Benson in 1880, you’d have witnessed the town’s economic lifeblood begin to drain away.

The new railroad hub in Benson drew merchants, settlers, and services that might’ve otherwise sustained Tres Alamos’ growth.

Your business, had you operated one in Tres Alamos, would have faced the impossible choice of relocating to Benson or watching your livelihood slowly wither as commerce and travelers followed the iron rails elsewhere.

Railroad’s Decisive Bypass

Although Tres Alamos once thrived as an essential stagecoach stop along southern Arizona’s east-west transportation corridor, its fate was sealed by critical railroad decisions in the late 1870s.

When Southern Pacific selected Yuma as their Arizona entry point in May 1877, they bypassed the traditional Tres Alamos route in favor of a more direct path to the San Pedro River, establishing Benson as the new commercial hub by 1880.

This transportation evolution delivered three fatal blows to Tres Alamos:

- The February 1877 territorial compromise mandated dual railroad routes that excluded the settlement.

- Stage service to Tres Alamos officially terminated in March 1879, eliminating its transportation relevance.

- Railroad expansion created new towns at strategic junctions rather than adapting to existing settlements.

You’re witnessing how a single infrastructure decision could instantly transform thriving communities into ghost towns.

Benson’s Economic Magnetism

The emergence of Benson as the region’s dominant commercial center in 1880 created an irresistible economic vacuum that rapidly drained Tres Alamos of its remaining energy.

Southern Pacific Railroad’s decision to bypass Tres Alamos proved fatal, as Benson’s allure drew merchants, ranchers, and families seeking better opportunities.

You’d have witnessed a swift economic migration as Tres Alamos lost its post office in 1886—a critical lifeline for isolated communities.

Benson offered what Tres Alamos couldn’t: reliable market access, protection from Apache raids, and integration with regional trade networks. Farmers and ranchers calculated the odds and relocated operations to safer ground.

As younger generations sought Benson’s prospects, Tres Alamos’ community fabric unraveled.

The once-promising settlement simply couldn’t compete with Benson’s transportation advantages and commercial momentum.

Visiting the Remains Today: What’s Left to See

Today, visitors to Tres Alamos will encounter little more than scattered remnants of what was once a bustling stagecoach stop in southeastern Arizona.

This ghost town sits in isolation, accessible only via rough unpaved roads that demand a high-clearance vehicle. You’ll find no standing structures—time and elements have reclaimed this historical site.

What you can still discover:

- Foundation stones and building rubble scattered across the desert landscape

- Fragments of daily life—broken glass, metal artifacts, and other historical remnants

- Faint traces of old wagon routes and roads etched into the terrain

You’re on your own here—no facilities, signs, or guided experiences exist.

Bring water and supplies, and prepare for solitude among the mesquite and creosote where history whispers through the desert silence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Famous Residents or Notorious Outlaws in Tres Alamos?

You won’t find famous residents or notorious outlaws who permanently settled in Tres Alamos, though travelers like stage operator Billy Ohnesorgen and lawman Dick Gird passed through this violent frontier outpost.

What Natural Disasters or Epidemics Affected Tres Alamos During Its Existence?

You’d have faced seasonal floods damaging river infrastructure and periodic disease outbreaks like malaria along the San Pedro Valley. Wildfires, drought, and extreme heat also challenged your frontier existence at Tres Alamos.

Are There Any Ghost Stories or Supernatural Legends Associated With Tres Alamos?

Like Odysseus’s wandering spirits, you’ll find no documented ghost sightings or haunted locations here. Historical records remain silent on supernatural legends that might’ve emerged from this abandoned settlement’s weathered ruins.

How Did Native American-Settler Relations Compare to Other Arizona Settlements?

You’ll find Tres Alamos mirrored regional patterns—cultural exchanges occurred alongside violent conflicts. Unlike settlements with negotiated conflict resolutions, the area experienced persistent Apache warfare following the Gadsden Purchase of 1853.

What Artifacts or Items Have Been Recovered From the Tres Alamos Site?

You’ll find Spanish Coronado Expedition artifacts including crossbow bolts and chain mail, everyday ghost town relics, and thousands of prehistoric indigenous items. These artifacts’ significance stems from their deep historical context.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tres_Alamos

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alamo_Crossing

- https://www.bensonvisitorcenter.com/history/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/tresalamos.html

- https://www.cochisecountyhistoricalsociety.org/journals/cchs-vol-35-no-02-fall-winter-2005.pdf

- https://www.wyattearpexplorers.com/billy-ohnesorgen–tres-alamos.html

- http://www.azbackcountryadventures.com/tres.htm

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NHSjfwV4qaw

- https://www.azcentral.com/story/travel/road-trips/2015/11/05/san-pedro-river-arizona-recreation-history/75046290/