Turret, Colorado began as a gold mining camp in 1897 after discoveries in Cat Creek valley. You’ll find this ghost town tucked in the mountains where it once thrived with 400 residents, complete with schools, stores, and saloons. Today, it’s strictly private property with no public access, unlike other Colorado ghost towns. The story of how Turret transformed from prosperous mining community to abandoned relic reveals fascinating chapters of western expansion.

Key Takeaways

- Turret began as Camp Austin in 1880 before becoming a mining boomtown with nearly 400 residents at its peak.

- Gold discoveries in 1897 sparked Turret’s growth, with the Gold Bug and Vivandiere mines extracting valuable ore from granite.

- The town featured schools, stores, saloons, and mining infrastructure before economic decline led to abandonment.

- WWII restrictions in 1944 caused Turret’s final economic collapse, transforming it into the ghost town that exists today.

- Turret is now a strictly private ghost town with no public access and numerous “no trespassing” signs.

The Gold Rush Origins of Turret

While the Pike’s Peak gold rush swept through Colorado Territory from 1858 to 1861 drawing an estimated 100,000 fortune seekers, Turret’s mining history began much later in 1897 when promising deposits were discovered in the Cat Creek valley.

Turret emerged decades after the initial Colorado gold findings, which included the 1850 Cherokee discovery at Ralston Creek in present-day Arvada and Eustace Carriere’s 1835 pure gold specimens that he unfortunately couldn’t relocate.

When miners finally struck gold in Turret, operations quickly expanded with the Gold Bug and Vivandiere mines becoming important producers.

Unlike earlier placer mining, Turret’s prospectors faced the unusual challenge of extracting gold from solid granite.

Despite this obstacle, the district soon attracted hundreds of miners who established a vibrant community, transforming the remote mountain location into a bustling settlement.

The town established a post office by 1898, serving the growing population of miners and businessmen who made Turret their home.

Today, visitors interested in exploring mining history are encouraged to visit other ghost towns nearby as Turret remains privately owned with a focus on preservation.

From Camp Austin to Mining Boomtown

You’re looking at a settlement that began after the 1880 Gold Bug Mine discovery but didn’t take formal shape until 1897 as Camp Austin, soon renamed to Turret as mining ambitions grew.

The town’s rapid development transformed it from a hopeful prospector’s camp into a bustling community with schools, stores, and saloons serving nearly 400 residents at its height.

While gold mining never delivered the anticipated riches, the discovery of high-quality “Salida Blue” granite in the early 1900s briefly sustained Turret’s economic significance before its eventual decline. The town was founded by Peter Schlosser who established the original town layout. Mining operations in the area extracted gold from quartz veins throughout the district until production ceased in 1939.

Gold Bug Discovery Spark

The transformative discovery of the Gold Bug Mine in 1897 marked a pivotal moment for what would become Turret, Colorado.

Situated at 8,681 feet in Chaffee County, this find sparked an unprecedented gold mining rush in the Cat Creek valley, which had previously focused solely on timber operations.

What made Gold Bug extraordinary was its remarkable yield—$4.50 to $10.00 worth of gold per ton extracted from solid granite, something previously unheard of in mining history.

This revelation triggered an immediate influx of miners, prospectors, and entrepreneurs to the area, including my great-grandfather Lewis who would later work the mines during the 1930s.

The economic impact was swift and dramatic.

The underground workings featured a 500-foot shaft that provided access to the rich deposits of gold, silver, and copper that made the mine so valuable to the region.

Renaming Marks New Era

Once a humble wood-cutting operation established by the Austin family in 1884, Camp Austin underwent a dramatic change in 1897 when Peter Schlosser formally laid out the settlement and renamed it Turret.

This renaming significance marked more than just a change in title—it represented the community evolution from an informal prospecting camp into a structured mining town with hopes for prosperity.

The change coincided with infrastructure development as Turret gained a post office, school, and various businesses serving its growing population.

While the Austins had struggled to find gold, the town’s eventual economic success came through the discovery of superior “Salida Blue” granite rather than precious metals.

The discovery of gold in Cripple Creek sparked renewed interest in the area, leading to important mining operations like the Jasper mine which was recorded in 1897 by Frank B. Keyes, Charles Klisinger, and Emil Becker.

Peak Mining Population

Transforming from Camp Austin’s modest beginnings, Turret quickly blossomed into a bustling mining community as gold fever gripped the region in the late 1890s.

The population swelled dramatically, reaching its zenith around 1902 with estimates suggesting 400-500 residents called this frontier outpost home.

The mining workforce thrived during this period, creating a diverse community:

- Miners and prospectors formed the backbone, extracting gold, silver, copper, and lead.

- Business owners established essential services—three saloons, hotels, and boarding houses.

- Skilled workers operated the Vivandiere and Gold Bug mines.

- Families settled, creating a proper town with a school and post office.

Located 14 miles north of Salida, Turret was once a vibrant community with pool halls, general stores, and multiple hotels serving the needs of its growing population.

You’d find this golden-era Turret vibrant and alive—a stark contrast to the ghost town it would eventually become after mining’s decline post-1910.

The town officially marked its end when the post office closed around 1941, signaling the final chapter of Turret’s once-prosperous mining community.

Peak Years: Life in Turret at Its Height

Following the 1897 gold discovery in Cat Creek valley, Turret experienced a remarkable period of growth that transformed it from a small mining outpost into a thriving community of up to 600 residents by 1902.

During these peak years, you’d find a bustling town where mining techniques yielded unprecedented returns—some ore samples produced $4.50 to $10.00 per unit of solid granite. One notable resident during this time was Pete G. Schlosser, who gained local fame for his unusual claim about tomatoes.

Mining’s golden touch transformed ordinary granite into extraordinary wealth, turning frontier dreams into tangible fortunes.

The social dynamics centered around a commercial district featuring multiple saloons, a hotel, boarding houses, and specialized businesses like the assay office and butcher shop. The Turret Wildcat newspaper documented the camp’s vibrant activity.

With railroad connections facilitating transportation of ore and supplies, and Chicago investors capitalizing on productive claims, Turret’s economic significance created an atmosphere of optimism and opportunity that defined this golden era of the settlement.

The Profitable Blue Granite Industry

While gold mining dominated Turret’s early economy, the area’s exceptional blue granite deposits emerged as a profitable parallel industry in the early 1900s, gaining significant momentum around 1904.

When you explore Turret’s history, you’ll find the granite quarrying operations provided essential economic stability as mining fortunes fluctuated. The blue granite, along with pink and green varieties, quickly gained recognition for qualities that rivaled top global quarries.

- Extraction required specialized equipment and skilled labor

- Products reached markets far beyond Colorado’s borders

- The distinctive fine-grained stone commanded premium prices

- Quarrying continued steadily even as mining booms waned

The economic significance of Turret’s granite industry extended beyond mere extraction—it established Colorado’s reputation in the national building materials market and created a legacy that outlasted many mining ventures.

Daily Life and Business in a Mountain Mining Town

Daily life in Turret went far beyond the clang of mining tools and rumble of granite quarries.

While mining powered Turret’s existence, the real story was found in its close-knit community life.

You’d find a surprisingly vibrant community where miners earning $2.50 per day could enjoy multiple amenities despite the harsh mountain environment.

The town hummed with daily routines centered around essential services—general stores, a meat market, bakery, and laundry.

Community events often unfolded in one of three saloons or the pool hall, where miners gathered after shifts.

The “Turret Wildcat” newspaper kept everyone informed of local happenings.

Families settled into small homes—some built on skids for mobility as mining activities shifted—while children attended the local school.

The post office (established 1898) connected residents to the outside world until 1939, long after mining declined post-1910.

Transportation and Connections to the Outside World

Isolated by rugged mountain terrain, Turret faced considerable transportation challenges that shaped its development and ultimate fate. Without direct rail access, miners had to haul ore by wagon to the Denver & Rio Grande branch line nearly a mile away, considerably increasing costs and limiting profitability.

You could reach Turret from Salida via:

- Alpine Trail – a doubletrack road leading into the settlement

- Stafford Gulch – a key access route to the townsite

- Mountain trails – accessible by pack animals but often impassable in winter

- Connections through Whitehorn – where residents sometimes utilized the railroad’s Calumet Branch

The lack of rail infrastructure directly serving Turret contributed heavily to its economic struggles, while nearby settlements with direct rail connections flourished.

This transportation disadvantage ultimately influenced Turret’s isolation and eventual abandonment.

The Gradual Decline of Turret’s Mining Economy

You’ll find the story of Turret’s economic decline traces a clear arc from promising gold discovery to profitable granite extraction before the final blow.

Initially, miners viewed the abundant granite as an obstacle until recognizing its superior commercial value, which ironically became the town’s economic mainstay after gold mining diminished.

When the U.S. Government halted all non-essential mining in 1944 during World War II, Turret’s already fragile economy collapsed, leading to its ultimate abandonment and change to the ghost town you can visit today.

From Gold to Granite

While Turret’s story began with the glitter of gold in the 1890s, its economic foundation gradually shifted as miners encountered a challenging reality beneath the surface.

The granite that initially frustrated gold extraction efforts eventually became the town’s economic salvation, transforming mining operations across the district.

What changed Turret’s fortunes:

- The discovery that “Salida Blue” granite held superior value for monuments and construction

- Peak granite mining in 1905 coincided with Turret’s most profitable mining year

- Denver buyers declared the local granite superior even to Gunnison’s renowned stone

- Economic shifts sustained the community until WWII restrictions halted operations in 1944

You can trace Turret’s evolution through this pivotal change from precious metals to building materials—a reflection of frontier resourcefulness amid challenging economic realities.

War Ended Everything

When the United States entered World War II, Turret’s mining economy faced its final challenge. In 1944, the federal government’s wartime restrictions halted non-essential mining operations, including Turret’s granite industry. This mining shutdown dealt the death blow to the town’s already fragile economy.

Unlike other resource-dependent communities, Turret never recovered after the war ended. With no economic incentive to return, former residents sought opportunities elsewhere. The war impact extended far beyond temporary disruption—it permanently altered the town’s trajectory.

Schools closed, businesses shuttered, and infrastructure crumbled as the population dwindled.

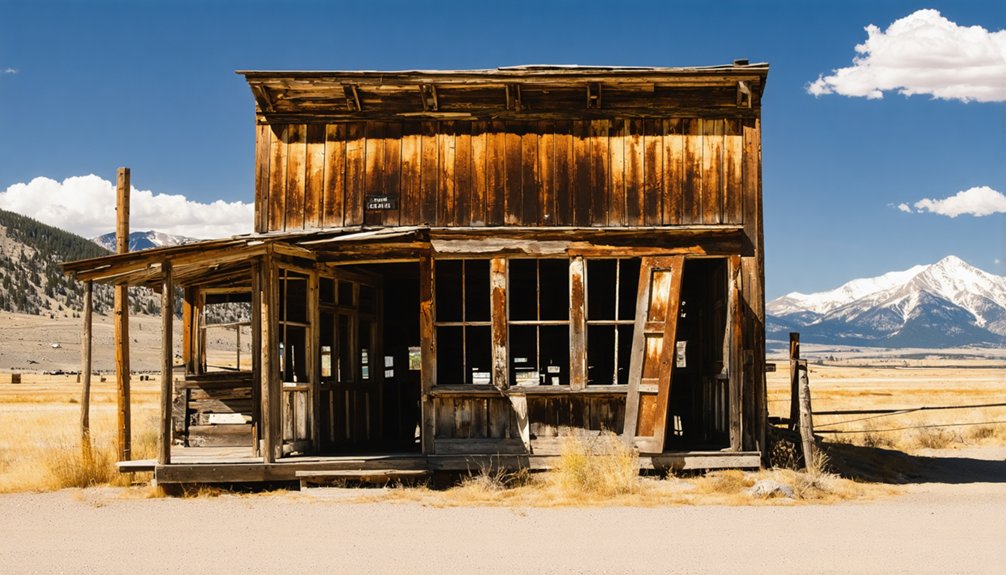

What you’ll find today are just the skeletal remains of a once-vibrant mining community—a few weathered log structures standing as silent witnesses to Turret’s abrupt end. The privately owned ghost town now serves as a historical reminder of how quickly prosperity can vanish.

What Remains: Ghost Town Structures and Ruins

Today’s Turret offers a fascinating glimpse into Colorado’s mining past, despite much of the town having succumbed to time and elements. The ghost town architecture reveals the framework of a once-thriving community, with dilapidated log cabins and building foundations scattered across private property.

Mining infrastructure remains visible, including abandoned quartz mines and the remnants of the Jasper mine operation.

When exploring the accessible areas, you’ll find:

- Precariously balanced structures overlooking the road into town

- Original log buildings alongside modern mountain homes with solar power

- Foundations of former hotels, saloons, and general stores

- Abandoned mine shafts and hoist mechanisms

These ruins tell a silent story of boom-and-bust mining life, though accessibility is limited as all property is privately owned.

Visiting Turret Today: Access and Preservation

Unlike many historic sites that welcome visitors, Turret stands as a strictly private ghost town with no public access permitted.

You’ll encounter numerous “no trespassing” and “private property” signs throughout the area, reflecting the owners’ serious Access Restrictions. Local residents are reportedly unfriendly toward trespassers, and authorities strictly enforce property laws.

The private owners actively maintain Preservation Efforts focused on protecting Turret’s historical integrity and tranquility. Their dedication keeps this granite mining town (not gold, as commonly misunderstood) undisturbed from commercial tourism.

Instead, redirect your exploration to nearby ghost towns like St. Elmo, Madonna Mine, or Arborville.

These alternatives welcome visitors with guided tours and amenities while satisfying your curiosity about Colorado’s mining history without legal consequences.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Paranormal or Ghost Stories Associated With Turret?

Based on available research, you won’t find documented ghost sightings or haunted locations in Turret. The abandoned mining town’s paranormal aspects remain unexplored in accessible historical records.

What Happened to Most of Turret’s Original Residents?

You’ll find that Turret’s original residents dispersed when mining ceased in 1944. Turret demographics show families relocated for jobs after the economic backbone collapsed, leaving behind their once-thriving mountain community’s history.

Is Camping Permitted in or Near Turret Today?

Picture yourself under starry Colorado skies—you can’t camp in Turret itself as it’s private property. However, you’ll find nearby campgrounds on public lands where camping regulations permit stays up to 14 days.

What Wildlife Can Visitors Expect to Encounter in Turret?

While exploring nature trails, you’ll likely encounter diverse wildlife species including mule deer, black bears, mountain lions, elk, golden eagles, bobcats, and various songbirds in this untamed mountainous region.

Were There Any Famous Outlaws or Notable Incidents in Turret?

Like shadows against canyon walls, Turret outlaws weren’t individually famous, but you’ll find the area served as part of wider outlaw corridors. No specific Turret incidents stand out in historical records.

References

- https://coloradoreflections.blogspot.com/2008/01/memories-of-turret.html

- https://salida.com/best-of-salida/ghost-towns/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/colorado/turret/

- https://arkvalleyvoice.com/history-lives-turret-whitehorn-and-smeltertown/

- https://turretcolorado.com/about

- http://coloradosghosttowns.com/Turret Colorado.html

- https://turretcolorado.com

- https://www.coloradocentralmagazine.com/the-calumet-branch-and-turret-by-dick-dixon/

- https://www.mindat.org/loc-14350.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-Yp2ZBaCPg