You’ll discover Vallecito, a enchanting Gold Rush ghost town born after the Murphy brothers’ 1852 gold discovery along Coyote Creek. Once Calaveras County’s second-largest gold producer, the town’s prosperity ended abruptly with the devastating 1859 fire that destroyed nearly 30 buildings. Today, you can explore California Historic Landmark No. 273 with its reconstructed 1851 stage station, iron-doored Cuneo Ruins, and Campo Santo cemetery. The whispers of prospectors still echo through these preserved ruins.

Key Takeaways

- Vallecito was a thriving Gold Rush town established in 1852 that became California’s second-largest gold producer in the region.

- The Great Fire of 1859 destroyed nearly 30 buildings, contributing to Vallecito’s eventual decline into a ghost town.

- Now designated as California Historic Landmark No. 273, the site features a reconstructed 1851 stage station.

- Mining evolved from simple placer techniques to hydraulic operations, with gold nuggets found weighing up to 27 pounds.

- Today’s ghost town includes the Cuneo Ruins, Campo Santo cemetery, and historic structures arranged around a central plaza.

Gold Rush Beginnings: The Birth of Vallecito

While California’s Gold Rush erupted with James Marshall’s famous discovery at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, it was along the banks of Coyote Creek where John and Daniel Murphy uncovered a treasure that would birth the settlement of Vallecito.

Initially dubbed “Murphys’ Old Diggins,” this mining settlement flourished when exceptionally rich deposits were found running beneath its center in 1852.

The Spanish name “Vallecito,” meaning “Little Valley,” was officially adopted in 1854, reflecting the influence of Mexican miners in the region. As word spread of gold nuggets weighing up to 27 pounds, fortune-seekers flooded the area. The town developed quickly with a distinctive central plaza layout where the earliest structures were simply ramadas and tents.

The once-quiet camp transformed almost overnight as miners employed various techniques—from simple panning to more complex “coyoteing”—extracting wealth from the ancient river channel below. By 1880, Vallecito had become the second largest producer of gold in the county, surpassed only by nearby Mokelumne Hill.

The Great Fire of 1859: Decline of a Boomtown

As flames engulfed the wooden structures of Vallecito on August 28, 1859, the boomtown’s future literally burned before its residents’ eyes. The blaze, originating near the Magnolia Saloon, devoured nearly 30 buildings in under 40 minutes, leaving no time to salvage possessions. Losses totaled $100,000—devastating the entire business district except for Traver’s store and a few other establishments.

The fire’s impact reverberated far beyond immediate destruction. Though some signs of community resilience emerged—like the swift rebuilding of Sperry and Perry Hotel by spring 1860—much of Vallecito was never restored. The tragedy mirrored similar disasters throughout Gold Rush communities, including Murphys which also suffered major fires in 1859.

This catastrophe accelerated the town’s decline as mining activities shifted elsewhere. With weakened infrastructure and dwindling investment, Vallecito gradually transformed from thriving boomtown to quiet ghost town, leaving only scattered stone structures as evidence to its once-vibrant Gold Rush heritage. Today, the site is recognized as California Historical Landmark #273 for its significance during the Gold Rush era.

Mining Evolution: From Placer to Hydraulics

You’ll discover that Vallecito’s gold extraction methods evolved dramatically from John and Daniel Murphy’s initial surface placer mining in 1848 to sophisticated hydraulic operations by the 1850s.

The early “coyoteing” technique of digging short shafts along Coyote Creek gave way to extensive hydraulic claims operated by companies like Pygall & Co., who used high-pressure water jets to erode gold-bearing hillsides. Mining operations often struggled with water seepage issues, impacting miners’ ability to reach deeper gold deposits.

This technological progression allowed miners to access deeper deposits within the ancient Tertiary river channels, where coarse gold concentrated near various bedrock types including limestone, schist, and granodiorite. During the 1930s, mining methods in the area evolved yet again with the introduction of drift mining techniques, particularly at the notable Vallecito Western mine.

Golden Rush Digging Techniques

Gold hunters in Vallecito initially employed simple but effective placer mining techniques to extract precious metal from the region’s riverbeds.

You’d find them hunched over shallow pans, swirling water to separate gold flakes from gravel—the most basic approach available.

As competition intensified, miners upgraded to rockers and cradles that processed larger volumes.

For improved efficiency, they often added mercury to these devices, which would trap fine gold particles that might otherwise be lost during processing.

The Long Tom and sluice boxes soon followed, allowing teams to work together, sifting more material through riffles that trapped heavier gold particles.

As mining evolved, elaborate sluice systems were developed for hydraulic operations, requiring significant investment capital and industrial labor to wash away overburden from gold-bearing gravels.

Water-Powered Fortune Hunting

When surface gold became increasingly scarce in Vallecito during the late 1850s, miners turned to the revolutionary technique of hydraulic mining. You’d have witnessed an engineering marvel as massive water cannons called monitors blasted hillsides with tremendous force, exposing ancient gold-bearing gravels previously unreachable.

Water management became the lifeblood of these operations, with elaborate systems of canals and reservoirs delivering vital high-pressure flows. Mining innovations like Anthony Chabot’s hydraulic nozzle transformed gold extraction from backbreaking labor to industrial-scale production, making Vallecito the county’s second-largest gold producer by 1880. These operations contributed to California’s economic boom that created numerous San Francisco millionaires who amassed fortunes from gold mining ventures. The technique had originated during the California Gold Rush, with the first documented use near Nevada City in 1853 by miner Edward Matteson.

Operations like Lone Star Claim yielded over $130,000, but success came with challenges. Excess water infiltration required costly tunnels and steam engines.

Haunted History: Ghostly Tales of the Stage Station

The lonely adobe walls of Vallecito Stage Station harbor more than just frontier memories—they’re said to be home to restless spirits from California’s tumultuous past.

Just a short distance away lies the history of Tehichipa ghost town, where remnants of the past linger in the arid landscape. Once a thriving hub during the gold rush, it now stands as a testament to the hopes and dreams of those who sought fortune. Visitors often recount eerie encounters, as the echoes of its storied past seem to resonate through the desolate streets.

When you visit this 1934 reconstruction of the once-vital Butterfield Overland stop, you’ll enter a domain where spectral sightings have persisted for generations.

The infamous “Lady in White” is said to wander the grounds, while ghostly encounters with a headless stagecoach driver—victim of an 1860s gold robbery—are part of local lore. His phantom coach supposedly completed its journey to Vallecito before vanishing into the desert night.

The station, established in 1851 by James Lassiter, served travelers, soldiers, and mail carriers crossing harsh terrain between San Diego and San Antonio.

Today, these tales attract paranormal enthusiasts seeking connection with the untamed spirit of the frontier.

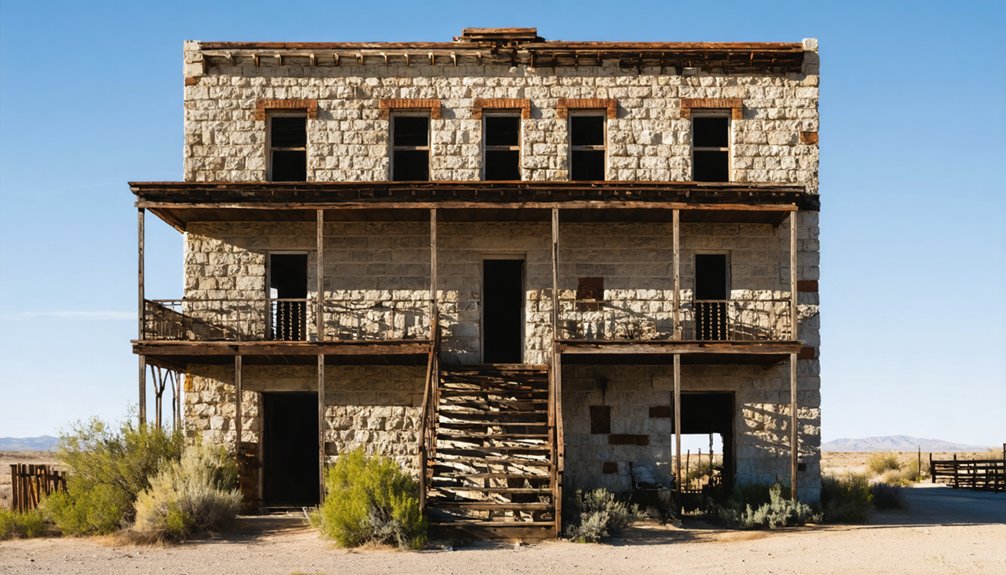

Surviving Structures: Architectural Legacy

Ruins of adobe and sod walls stand as silent witnesses to Vallecito’s architectural heritage, showcasing the pragmatic ingenuity of frontier builders. The 1934 reconstructed stage station faithfully preserves the architectural significance of James Lassiter’s original 1851 settlement, where sod construction represented adaptation to harsh desert conditions.

The weathered walls of Vallecito whisper stories of pioneer resourcefulness, where harsh desert necessities birthed innovative frontier architecture.

When you visit today, you’ll find:

- The meticulously reconstructed main station building maintaining period-accurate design elements

- Visible foundation remnants of original outbuildings that once supported stagecoach operations

- The nearby Campo Santo cemetery with weathered markers of early settlers

- Desert landscape surrounding structures that contextualizes the builders’ material choices

These preserved elements offer you a rare glimpse into California’s transportation history while honoring the resourcefulness of those who established this essential waypoint.

Modern-Day Vallecito: Preserving the Past

When you visit Vallecito today, you’ll find the 1934 reconstruction of the stage station standing as a symbol of preservation efforts that earned the site California Historic Landmark status No. 273.

The small cemetery and remaining structures are carefully maintained within Vallecito Regional Park, balancing historical protection with public access.

Interpretive programs highlight both the factual emigrant trail history and the colorful legends of the phantom bride, creating a multi-layered educational experience for tourists seeking California’s desert heritage.

Ruins and Standing Structures

Standing amid the sun-scorched hills of present-day Vallecito, you’ll encounter a remarkable collection of architectural remnants that tell the story of a once-thriving mining community.

The rugged rhyolite tuff blocks, transported from Altaville quarry, form the backbone of structures that have withstood time’s relentless march.

During your ruins exploration, you’ll discover:

- The Cuneo Ruins (1851) with original iron doors still guarding what was once a mining supply store

- Remnants of buildings arranged around a central plaza, reflecting Mexican settlement traditions

- The historic town bell, now mounted on a stone monument after its oak support fell in 1939

- Partially preserved structures like the former post office opposite the Cuneo ruins

These features highlight the architectural significance of this desert outpost, where minimal modern intrusion allows genuine glimpses into 1850s frontier life.

Historic Preservation Efforts

Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, Vallecito’s historic significance has been formally recognized and protected through dedicated preservation initiatives. The site’s designation as California Historical Landmark No. 273 established critical legal protections against demolition, looting, and inappropriate development.

You’ll find the present structure is actually a 1934 reconstruction of the original 1851 stage station built by James R. Lassiter. This restoration carefully balanced historic integrity with functional requirements, preserving construction methodologies while making the site accessible to visitors.

The integration into Vallecito Regional Park guarantees professional management and sustained preservation strategies.

While exploring the grounds four miles northwest of Agua Caliente Springs on County Road S-2, remember that treasure hunting is prohibited by law—these preservation measures protect both the physical structures and the rich historical narrative of this desert oasis.

Tourism and Education

Today’s Vallecito offers visitors far more than a glimpse into California’s pioneering past, having evolved into a multifaceted destination that balances historical reverence with modern recreational opportunities.

The tourism impact extends across educational programs that immerse you in both geological wonders and Gold Rush heritage.

When visiting this transformed ghost town, you’ll discover:

- Moaning Cavern’s 180-foot descent via a historic spiral staircase built in 1922

- Hands-on gold panning experiences that connect you to the region’s mining legacy

- Award-winning wineries featuring local vintages and special events throughout the year

- Paranormal tourism centered around the reportedly haunted Vallecito Stage Station

Educational exhibits complement these attractions, providing context about cave formation, mining techniques, and the cultural significance that shaped this distinctive corner of Gold Country.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Vallecito Get Its Name?

You’re staring at the most fascinating naming origins in California history! Vallecito got its name when Mexican miners renamed “Murphy’s Old Diggings” to this Spanish term meaning “Little Valley,” perfectly describing the site’s geography around 1854.

Where Exactly Is Vallecito Located Within California?

You’ll find Vallecito nestled in Calaveras County’s Sierra Nevada foothills at 38.09°N, 120.47°W, elevation 1,762 feet. It’s positioned 4.5 miles east of Angels Camp and 3.3 miles south of Murphys along Highway 4.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Vallecito Area?

You’ll discover the Kumeyaay (Diegueño) tribe originally inhabited Vallecito, establishing the village of Hawi there. Their rich cultural heritage included skillful resource management across territories extending into modern Baja California.

Can Visitors Pan for Gold in Vallecito Today?

Ironically, you’re chasing yesterday’s fortune today. Yes, you can pan for gold in this area, experiencing the historical significance of the Gold Rush while using traditional methods—just verify claim rights first.

Are There Guided Tours or Annual Events in Vallecito?

You’ll find guided exploration at Moaning Caverns Adventure Park year-round, with historical reenactments and community events during summer and fall. The Vallecito Stage Station opens seasonally from Labor Day through May.

References

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ca-vallecito/

- https://roadtrippers.com/magazine/vallecito-county-park-california/

- https://www.calaverashistory.org/vallecito

- http://cali49.com/hwy49/2013/12/6/vallecito

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vallecito

- https://www.californiahistoricallandmarks.com/landmarks/chl-273

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=6841

- https://ohp.parks.ca.gov/ListedResources/Detail/273

- https://www.calaverashistory.org/mining-in-the-douglas-flat-vallecito-area

- https://westernmininghistory.com/library/402/page1/