Weaver, Arizona began as a booming mining settlement in 1863 after Pauline Weaver discovered rich placer gold deposits at nearby Rich Hill. You’ll find this ghost town evolved from a thriving community of 3,500 to an abandoned site following gold depletion in the 1890s. Miners faced harsh conditions, rampant lawlessness, and economic uncertainty while extracting $500,000 in gold nuggets. Today’s ruins—machinery, stone structures, and cemetery—reveal untold stories of Arizona’s territorial mining frontier.

Key Takeaways

- Weaver was established after the 1863 gold discovery at Rich Hill, growing rapidly before declining to ghost town status.

- The mining district yielded approximately $500,000 in gold nuggets during its peak production period.

- The town once hosted around 3,500 residents before placer gold depletion led to economic collapse.

- Lawlessness became rampant as mining declined, with criminal gangs controlling the increasingly desperate community.

- Today, visitors can explore ruins including ore crushers, stamp mills, a stone house, and a historic cemetery.

The Gold Rush Beginnings: Weaver’s Birth in 1863

While the American Civil War raged in the East, a momentous discovery in the Arizona Territory sparked one of the West’s most significant gold rushes.

As eastern battles raged, Arizona Territory’s golden discovery ignited a rush that would reshape the American West.

In May 1863, Pauline Weaver led a party of prospectors including Jack Swilling and Abraham Peeples to Rich Hill, where they accidentally found placer gold deposits lying on the surface of a high mountain flat.

This gold discovery quickly transformed the landscape. The Weaver mining district was established, and the settlement initially called Weaverville honored the expedition’s leader.

You’ll find that community formation happened rapidly, with up to 1,000 Americans and Mexicans flocking to the area. Settlements emerged around Rich Hill and Weaver gulch, establishing what would become one of America’s richest placer gold regions. The area became infamous for its lawlessness, with robbers and thieves making the town their preferred hideout. The nearby Antelope Creek was named after wildlife killed by Weaver’s expedition during their initial exploration of the region.

Striking It Rich: Mining Operations on Rich Hill

When gold was discovered at Rich Hill in 1863, the area quickly emerged as one of Arizona Territory’s most significant mineral producing regions.

The district’s unique gold geology featured granite intrusive cutting through schist with east-west quartz veins, creating perfect conditions for gold deposition.

You’d find miners employing various placer techniques across the hill’s summit, slopes, and adjacent gulches. They extracted approximately $500,000 in coarse gold nuggets and slugs during peak production.

While individual prospectors panned and sluiced surface deposits, larger operations like the Hayden Mine (Rich Hill Consolidated Gold Mines) developed patented claims and drove deeper into the earth’s veins.

The area’s productivity continues attracting modern enthusiasts, with numerous prospecting associations maintaining claims where you can still find gold using the same fundamental techniques. Rich Hill is situated in the Weaver Mining District between Antelope Creek and Weaver Creek in Yavapai County, Arizona.

Rich Hill placers were extraordinarily productive, reportedly yielding more gold than any comparable area in the United States.

Boom to Bust: The Rise and Fall of a Mining Town

Weaver’s rapid transformation from a bustling gold mining settlement of 1,000 residents to an abandoned ghost town mirrors the classic boom-to-bust cycle of Western mining ventures.

You’ll find that the area’s lawless reputation intensified as economic pressures mounted, with the Congress Mine’s 1910 closure marking the beginning of the end despite substantial remaining gold reserves. The nearby Rich Hill discovery, which produced over 110,000 ounces of gold, had initially attracted miners to the region during Arizona’s territorial period.

The mining relics you’ll encounter today—from massive tailings piles to deteriorating structures—stand as silent witnesses to both the district’s $16 million gold production legacy and its abrupt economic collapse. Located on the south flank of the Weaver Mountains, the area’s extensive 40-square-mile placer grounds once drew prospectors from across the territory.

Gold Rush Beginnings

The discovery of gold near Antelope Creek in 1863 ignited one of Arizona Territory’s most significant mining booms, transforming a remote wilderness into a bustling frontier economy.

Prospectors Pauline Weaver and Abraham Peeples led the expedition that stumbled upon what became known as the “Potato Patch” when a Mexican member discovered large nuggets on Rich Hill while searching for a stray horse.

This discovery established the Weaver District, which developed into Arizona’s richest placer gold producer. Gold prospecting techniques initially focused on surface mining, with claims like Devil’s Nest and Leviathan quickly staked.

Mining community dynamics evolved rapidly as the towns of Weaver, Octave, and Antelope Station emerged to support the influx of fortune-seekers. By 1868, Antelope Station alone hosted approximately 3,500 residents, serving as an essential supply hub for the expanding mining operations. The area’s economic significance was further cemented when the stagecoach stop became crucial for delivering vital supplies to the growing mining community.

Pauline Weaver’s earlier gold discoveries near La Paz in 1862 had already established him as a skilled prospector in the territory before his more famous Rich Hill expedition.

Lawless Final Days

As placer gold production from Rich Hill dwindled in the 1890s, Weaver’s economic foundation crumbled, triggering a rapid descent into lawlessness that would ultimately seal the town’s fate.

The exodus of established families left a vacuum filled by desperate miners and outlaws. By 1898, local newspapers identified Weaver as headquarters for a “cutthroat gang” under a figure known as the “King of Weaver.”

Gang violence flourished with reported murders and ambushes becoming commonplace, accelerating community breakdown. During this period, Arizona was still in its territorial period, awaiting statehood that would only come in 1912, leaving frontier towns with limited law enforcement resources.

The combination of closed mines, escalating crime, and vanishing opportunity proved fatal. Between 1898-1899, residents “stampeded” to nearby Congress, leaving only two or three inhabitants by early 1899.

What remained were deteriorating stone structures—silent witnesses to Weaver’s lawless final chapter, a town undone by economic collapse and the resulting social disorder.

Abandoned Mining Relics

Today’s silent, crumbling remnants of Weaver tell a complex story of boom-to-bust mining economics that shaped Arizona’s territorial development.

As you explore the ghost town, you’ll find evidence of the area’s former prosperity—massive tailings from the Congress Mine containing 2.5 million tons of potentially recoverable material, abandoned machinery from operations that yielded over 110,000 ounces of gold from Rich Hill, and the weathered rock structures that once housed a thousand-strong population.

- Historical artifacts revealing the shift from placer to lode mining techniques that defined the district’s evolution

- Claim markers and processing equipment showcasing the east-west strike pattern that made Weaver uniquely productive

- Crumbling infrastructure highlighting how freight costs, not ore depletion, ultimately doomed profitable extraction

The gold deposits found here were primarily located within gently NNW-ward dipping fault zones, which miners followed in their quest for fortune.

Lawless Frontier: Gangs and Violence in Late 19th Century Weaver

While placer mining operations declined in Weaver during the late 19th century, the town’s isolation and diminishing economic prospects created ideal conditions for lawlessness to flourish.

The gang dynamics in Weaver revolved around figures like Charles Stanton, who recruited violent individuals to strengthen his position. Criminal networks formed informally, binding together fugitives and outlaws who sought refuge from authorities elsewhere.

You’d witness these gangs engaging in robbery, intimidation, and territorial violence with alarming frequency.

Following William Segna’s murder, the town’s reputation for danger reached new heights, prompting law-abiding residents to flee. Local law enforcement proved woefully inadequate against the entrenched criminal element.

Newspapers openly called for Weaver’s eradication, highlighting its status as an outlaw haven. The town ultimately collapsed under the weight of its violent legacy.

Daily Life in a Wild West Mining Community

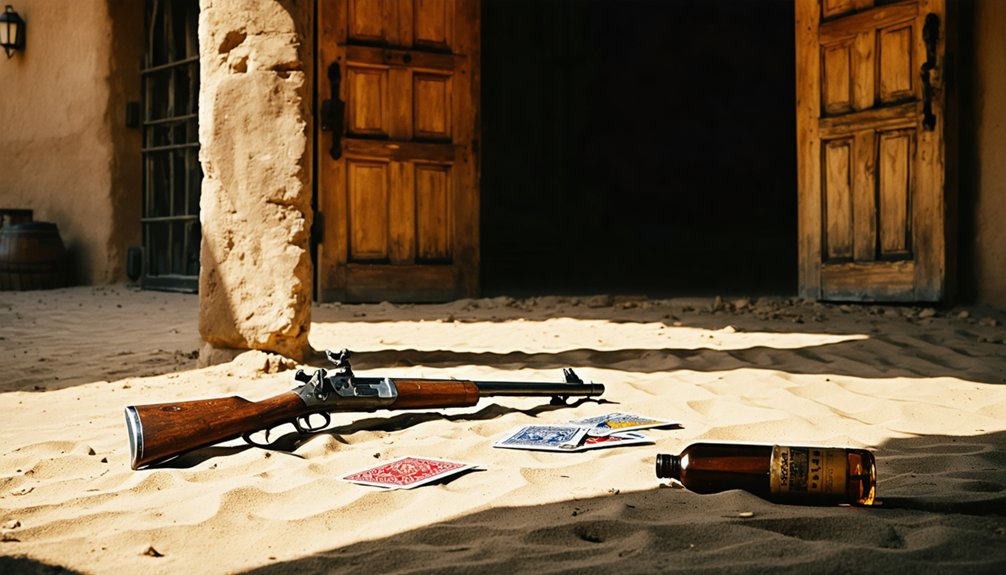

As you walked through Weaver’s mining community in the 1890s, you’d witness miners trudging from cramped quarters to dangerous tunnels, working with primitive tools and minimal safety measures in their quest for gold.

With law enforcement scarce and the town’s reputation for lawlessness growing after the placer deposits declined, you couldn’t count on authorities to maintain order amid the rough society of prospectors, blacksmiths, and laborers.

Your daily existence would revolve around mining operations, where Mexican and American workers toiled side by side in harsh conditions, often gathering informally after work in what remained of a once-booming frontier settlement that had declined from its 1,000-person peak.

Gritty Miner Existence

Life in Weaver’s mining community embodied the harsh realities faced by prospectors throughout Arizona’s territorial period. Your gritty survival depended on maneuvering constant dangers—injuries, disease outbreaks, and natural disasters plagued daily existence.

Earning barely enough to sustain yourself, you’d contend with inadequate housing in tent cities lacking basic infrastructure.

Miner camaraderie developed despite challenging conditions:

- You’d face physical exhaustion from labor-intensive work while battling environmental hazards like dust that caused “miner’s lung”

- Your claim could dry up without warning, forcing relocation or employment under company control

- You’d struggle with fuel scarcity, hauling limited mesquite or ironwood by wagon for essential operations

This economic insecurity shaped Weaver’s transient community, where both American and Mexican workers lived under the boom-bust cycle of mining prosperity.

Law’s Tenuous Grip

The tenuous grip of law in Weaver ultimately collapsed under the weight of economic decline and geographic isolation.

As placer gold dwindled, the population of several thousand miners scattered, leaving behind a vacuum quickly filled by criminal leadership. By 1898, the notorious “King of Weaver,” a blind man embodying three decades of lawlessness, presided over systematic theft and murder operations.

Authority challenges proved insurmountable in this remote outpost sixteen miles from Wickenburg. Without effective law enforcement to counter the cutthroat gang, newspapers called for the town’s complete destruction.

The mountainous terrain further complicated intervention efforts from territorial authorities. The community’s institutional framework disintegrated when remaining residents fled to Congress by 1899, leaving behind only two or three souls.

What Remains Today: Exploring Weaver’s Ghost Town Ruins

Standing silent against the Arizona desert backdrop, Weaver’s ghost town ruins offer visitors a glimpse into the mining community that once thrived here.

You’ll find rusting ore crushers and stamp mills scattered across the landscape, telling the story of Arizona’s industrial past. A partially intact stone house with adobe walls stands as evidence to 19th-century building techniques, while the partly restored cemetery preserves the human dimension of this historical site.

- Weathered machinery remnants define Weaver’s historical significance as an industrial rather than residential settlement.

- Desert vegetation gradually reclaims the site, with cacti growing among ruins in a display of natural persistence.

- The visitor experience remains authentically minimal, with few interpretive elements interrupting your connection to the raw historical remnants.

Weaver’s Place in Arizona Mining History

When prospectors discovered placer gold in Weaver Gulch in 1863, they unknowingly initiated Arizona’s first significant gold rush and established what would become the oldest mining district in Yavapai County.

The Rich Hill discovery represented a pivotal change from Spanish silver operations to American gold rushes, with surface deposits ranking among the richest in United States history.

The economic impact of Weaver’s mines was extraordinary, particularly the Congress Mine which generated approximately $16 million in gold and silver during its 26-year operation.

Mining technology evolved as operations shifted from simple placer mining to more sophisticated underground excavation.

This district’s exceptional wealth supported thousands of residents and drove regional development until the 1890s, when depleted deposits and rising operational costs triggered Weaver’s dramatic decline into lawlessness and eventual abandonment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous Outlaws Known to Have Hidden in Weaver?

Yes, Francisco Vega and his Mexican gang dominated the area. Outlaw legends suggest they protected hidden treasures while transforming Weaver into a haven for desperadoes escaping law enforcement.

What Happened to the Johnson Mine After It Caved In?

Like a tomb sealing history, after the Johnson Mine collapse, operations ceased permanently. You’ll find its patented ground remained idle, with eastern heirs uninterested in reviving mining operations, leaving this golden legacy untouched.

Did Any Indigenous Peoples Interact With the Weaver Settlement?

Yes, Apache groups regularly interacted with Weaver settlement through conflict and limited cultural exchange. Pauline Weaver’s Cherokee heritage facilitated complex relationships despite documented indigenous raids on miners throughout the settlement’s troubled history.

What Natural Disasters or Extreme Weather Affected Weaver’s Development?

Dramatic droughts devastated your settlement’s water supply, hampering mining operations. You’d also face flash floods that caused significant flood damage to buildings and infrastructure, further challenging Weaver’s tenuous existence in Arizona’s harsh climate.

Are There Any Documented Paranormal Stories Associated With Weaver?

You’ll find Weaver’s paranormal reputation stems primarily from unverified local legends. While ghost sightings are mentioned in anecdotal accounts around haunted locations like the cemetery, no formal paranormal investigations have documented these claims scientifically.

References

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/az/weaver.html

- https://winfirst.wixsite.com/arizonamininghistory/weaver

- http://www.ghosttowngallery.com/htme/weaver.htm

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCmbpQwvskM

- https://thelbsbigadventures.com/2022/05/01/looking-for-ghost-towns-in-the-weaver-mountains/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weaver

- http://minerdiggins.com/Ripple/b091810b.html

- http://www.echoesofthesouthwest.com/2016/03/the-ghost-town-of-weaver.html

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Weaver

- https://www.apcrp.org/Weaver/Weaver_041008.htm