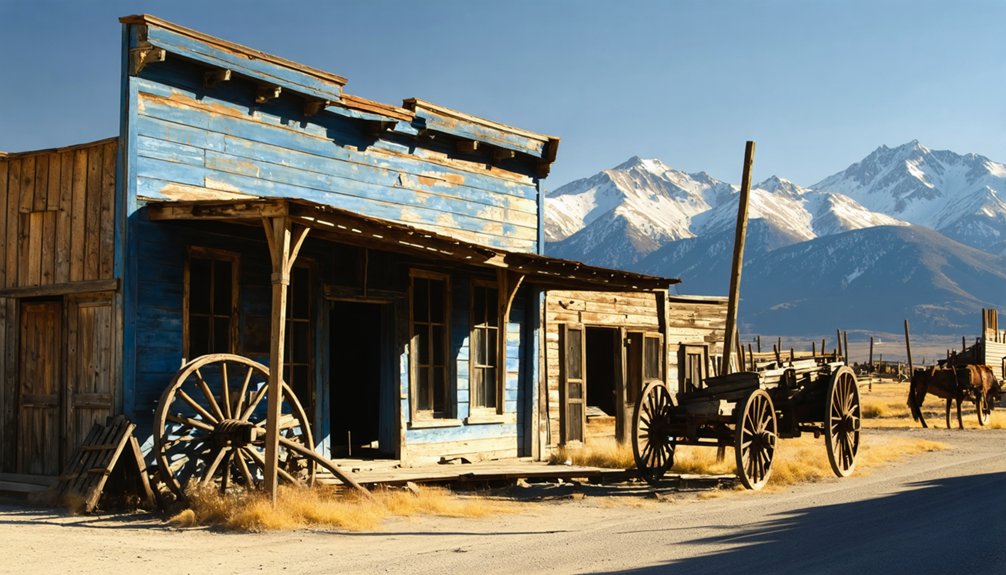

You’ll discover fascinating historic secrets in gold rush ghost towns like Bodie’s perfectly preserved “arrested decay” buildings, Virginia City’s revolutionary mining innovations, and Bannack’s controversial territorial capital history. These abandoned settlements reveal dramatic boom-bust cycles where populations surged to thousands before economic collapse. Each weathered structure tells stories of lawlessness, cultural diversity, and technological advancement that shaped American identity. The dusty streets await your footsteps through America’s transformative frontier period.

Key Takeaways

- Bodie preserved in “arrested decay” reveals California mining life with over $38 million in gold production and notorious lawlessness.

- Virginia City’s Comstock Lode generated $230 million in silver, introduced mining innovations, and supported the Union during the Civil War.

- Bannack, Montana’s first territorial capital, holds controversial Sheriff Plummer’s story and over 60 original structures showing pioneer craftsmanship.

- Animas Forks, one of America’s highest mining settlements, featured advanced amenities like electricity before its abandonment after 1910.

- Timbuctoo’s ruins tell of environmental devastation from hydraulic mining that led to landmark legal decisions affecting Western water rights.

Bodie: California’s Time Capsule of Gold Rush Glory

Although now standing as a silent memorial to California’s gold-mining past, Bodie once thrived as one of America’s most notorious boomtowns following William S. Bodey’s 1859 discovery.

After a mine cave-in revealed rich ore in 1875, Bodie’s population exploded to nearly 10,000 residents by 1877-1882, with approximately 2,000 buildings at its peak.

The 1875 ore discovery transformed Bodie from mining outpost to boomtown metropolis, bursting with thousands of fortune-seekers and their hastily-built dwellings.

This lawless settlement rivaled Tombstone and Deadwood in its wild reputation, producing over $38 million in precious metals before its inevitable decline. The phrase “Badman from Bodie” emerged around 1880, capturing the town’s dangerous character.

When mining yields dropped and fires ravaged the town, Bodie’s fate was sealed. The last mine closed in 1942.

Today, you’ll find Bodie history preserved in “arrested decay” as California’s official ghost town.

The remaining 110-200 structures stand frozen in time, offering an authentic glimpse into the unstaged realities of frontier life. Visitors can explore the original relics inside buildings like the church, schoolhouse, barbershop, and saloon.

The Silver Transformation: Calico’s Journey From Boomtown to Tourist Destination

While Bodie exemplified California’s gold mining heritage, about 300 miles southeast in the Mojave Desert, Calico emerged with a distinctly different story centered on silver.

Discovered in 1875, Calico’s fortunes soared after 1881 when the Silver King Mine sparked a rush that swelled the population to nearly 3,000.

You’ll find Calico’s economic shifts mirrored America’s broader mineral economy—producing $13-20 million in silver before plummeting prices in the 1890s decimated operations.

By 1907, this once-thriving hub with 500 mines stood abandoned.

Walter Knott’s 1950s restoration transformed Calico from ruin to tourism success, preserving its mining heritage while creating an accessible window into western expansion.

Today, this state historical landmark offers you immersion in authentic boom-and-bust cycles that shaped California’s desert frontier.

Much like the miners who traveled difficult routes during the California Trail migration of forty-niners, silver seekers endured harsh desert conditions to reach Calico’s promising deposits.

Visitors can now experience the town’s rich history through mine tours and engaging gunfight stunt shows that bring the Old West back to life.

Virginia City: Living Legacy of the Comstock Lode

Unlike its California counterparts, Virginia City stands as the crown jewel of Nevada’s mining heritage, emerging in 1859 following Henry Comstock’s discovery of the legendary Comstock Lode.

This National Historic Landmark‘s Comstock legacy extends beyond its $230 million silver production that bolstered the Union during the Civil War and catalyzed Nevada’s statehood.

You’ll witness revolutionary mining innovations that transformed industrial practices nationwide—square-set timbering, air compression drills, and safety cages that allowed miners to extract riches from increasingly dangerous depths. The history of these innovations is marked by intense legal disputes that consumed an estimated 20% of the $50 million in ore extracted from 1859 to 1865.

The sophisticated Virginia and Truckee Railroad and high-pressure water system demonstrate engineering prowess that supported this 25,000-resident boomtown. The devastating Great Fire of 1875 destroyed much of the city but led to remarkable rebuilding efforts completed within just one year.

When you explore Virginia City today, you’re walking through living history—not an abandoned ghost town but a vibrant community where over two million annual visitors experience preserved 19th-century architecture and operational mining relics.

Bannack’s Territorial Rise and Preservation Story

When you visit Bannack, you’ll stand in Montana’s first territorial capital from 1864, where the infamous Sheriff Henry Plummer met his controversial end at the hands of vigilantes debating his alleged leadership of the “Innocents” outlaw gang.

The town’s remarkably intact pioneer structures—ranging from simple miners’ cabins to the imposing Masonic lodge—offer an authentic glimpse into frontier architecture that survived the boom-bust cycle that transformed a 3,000-person boomtown into a carefully preserved ghost town. The schoolhouse built by the Bannack Masonic Lodge No. 16 in 1874 served the community for nearly 70 years before the town’s decline. Following the gold discovery on Grasshopper Creek, Bannack experienced a population explosion reaching up to 5,000 residents during its peak.

Bannack’s preservation as a state park now allows you to walk the same boardwalks where miners once carried gold with extraordinary 99.5% purity, maintaining the physical legacy of Montana’s earliest territorial governance before the capital shifted to Virginia City.

First Territorial Capital

Bannack’s ascension to political prominence began in 1864 when this burgeoning gold camp, established just two years earlier along Grasshopper Creek, was designated Montana Territory’s first capital.

Under Governor Sidney Edgerton’s leadership, the first territorial legislature convened here, establishing the foundation for Montana’s governance structure while the population had swelled from 400 to approximately 3,000 residents.

This period in Bannack history represents a fascinating dichotomy—a town simultaneously attempting for political legitimacy while grappling with lawlessness. Edgerton was a prominent Vigilante who participated in efforts to restore order during a time of rampant crime.

The territorial governance experiment proved short-lived, as the capital relocated to Virginia City in 1865 following richer gold discoveries there.

The town ultimately became a Montana state park, preserving its buildings and historical significance for future generations to appreciate.

Bannack’s political decline continued when it lost its county seat status to Dillon in 1881, though its preserved structures now stand as proof to Montana’s territorial beginnings and frontier democracy.

Notorious Outlaw Sheriff

While Montana Territory was establishing its formal governmental structures, the infamous Henry Plummer emerged as one of Bannack’s most controversial figures, embodying the tension between order and lawlessness that defined frontier communities.

Elected sheriff in May 1863, Plummer’s legacy remains fiercely contested. While respected by some residents, he allegedly orchestrated the “Innocents,” a gang targeting gold shipments along mining routes.

Political tensions complicated matters—vigilantes, mainly Republican Masons, sought to secure Union gold flow by eliminating Democratic influence.

Without formal trial, vigilante justice claimed Plummer on January 10, 1864, when he was hanged alongside his deputies. A posthumous trial in 1993 ended with a hung jury, illustrating how his guilt remains unresolved.

This complex power struggle reflected broader partisan dynamics rather than simple criminality, leaving Bannack with a haunting historical question of whether justice or political conspiracy prevailed.

Preserved Pioneer Architecture

Beyond Sheriff Plummer’s contested legacy lies the architectural proof of Bannack’s rapid evolution from mining camp to territorial capital.

When you walk Bannack’s streets today, you’re witnessing authentic pioneer craftsmanship that emerged during Montana’s first gold rush.

The Assay Office—crucial for verifying the region’s remarkably pure 99% gold—stands among the town’s oldest structures.

Brick buildings arose from safety concerns, including a courthouse and Methodist church constructed during Native American conflict periods.

The Governor’s Mansion represents Bannack’s brief glory as territorial capital in 1864.

What makes Bannack exceptional is the state’s thorough architectural preservation efforts begun in the 1950s.

Despite the town’s abandonment following richer strikes in Virginia City and the devastating railroad bypass of the 1880s, over sixty original structures remain intact for you to explore.

Animas Forks: Mining Life at Extreme Elevations

Perched at one of the highest elevations of any mining settlement in the United States, Animas Forks represented the extraordinary determination of prospectors willing to endure extreme conditions for potential riches. Following the 1873 gold and silver discoveries, this remote community quickly grew to 450 summer residents by 1883, establishing itself as a proof of high altitude living despite brutal winters and avalanche threats.

The mining hardships were offset by surprising amenities—electricity, telephones, and telegraph services sustained the town alongside four saloons, a hotel, and boarding houses accommodating 150 men.

The massive Gold Prince Mill, constructed in 1904 as Colorado’s most expensive mill, symbolized Animas Forks’ fleeting prosperity before its gradual abandonment following the 1910 mill closure and subsequent economic decline.

Hidden Gems: Lesser-Known Mining Settlements Along Gold Country

While exploring California’s mining heritage, you’ll encounter lesser-known settlements like Timbuctoo, which holds untold stories of racial diversity and entrepreneurship among early miners.

Ballarat’s mysteries remain largely undiscovered, with its remote Death Valley location concealing artifacts that reveal supply networks essential to isolated mining operations.

Sierra mining migrants established transient communities like Bennettville and Forest City, demonstrating how geographical challenges shaped settlement patterns and preservation efforts across Gold Country.

Timbuctoo’s Untold Stories

How did a small mining settlement named after a distant African city become one of the Gold Rush‘s most intriguing forgotten chapters? Founded in 1855, Timbuctoo rapidly grew to 1,200 residents through hydraulic mining prosperity, boasting impressive architecture including a Wells Fargo office with distinctive red-brick façade and a theater seating 800.

When you explore Timbuctoo’s complex legacy, consider:

- Its strategic positioning on a Yuba River bluff that prevented flooding while enabling access to gold-bearing sandbars

- The environmental devastation hydraulic mining caused, ultimately leading to the landmark 1884 Sawyer Decision

- Its commercial sophistication with banks, bakeries, and even an ice skating rink

- The rapid abandonment following the court ruling that prohibited the town’s economic lifeline

Undiscovered Ballarat Mysteries

Far from the familiar northern goldfields that birthed towns like Timbuctoo, an entirely different gold rush settlement emerged in the harsh Mojave Desert landscape. Ballarat, named after its Australian counterpart, thrived briefly as a critical supply hub for Panamint Range miners between 1897-1905.

You’ll find Ballarat legends embedded in its remnants—the town that once boasted seven saloons but never a single church. The Pleasant Canyon Loop Trail reveals mining relics from the once-productive Ratcliff Mine that yielded 15,000 tons of gold ore.

Characters like “Shorty” Harris and “Seldom Seen Slim” walked these dusty streets, their stories preserved alongside crumbling foundations.

Unlike northern settlements, Ballarat persisted in isolation, with minimal preservation attempts. Today, a solitary caretaker watches over this desert ghost town, its adobe structures slowly returning to the earth.

Sierra Mining Migrants

As the California Gold Rush fever spread through the Sierra Nevada foothills in the mid-1800s, a remarkable tapestry of cultural diversity emerged in lesser-known mining settlements that historians often overlook.

These transient settlements attracted an unprecedented migrant diversity from across the globe, creating unique multicultural communities that rose and fell with gold fortunes.

- Italian migrants from Genoa brought agricultural expertise, establishing permanent roots that anchored some communities beyond gold depletion.

- El Dorado emerged rapidly around Mud Springs watering hole, housing 462 residents by 1850.

- Small mining camps formed around water sources but remained dependent on gold yields, often disappearing when deposits waned.

- Diverse populations including Chinese, Mexicans, Basques, and Ottoman migrants contributed distinct cultural elements, despite experiencing social tensions.

You’ll find these forgotten communities preserved today at sites like Empire Mine and Bodie.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Ghost Towns Experience Paranormal Activity During or After Mining Operations?

You’ll find that paranormal activity manifests primarily after operations ceased. Paranormal investigations document ghostly encounters stemming from tragic mining accidents, cultural conflicts, and sudden abandonment of these once-thriving communities.

What Valuable Artifacts Remain Undiscovered in These Abandoned Mining Towns?

With $30 million in gold extracted from Bodie alone, you’ll find lost treasures like mining equipment, opium den artifacts, and hidden relics beneath dry-preserved structures awaiting your analytical exploration.

How Did Indigenous Populations Interact With Mining Settlements?

Indigenous peoples experienced violent dispossession as you’ll discover, yet maintained cultural exchange through labor systems and occasional resource sharing despite devastating environmental impacts on their traditional hunting and gathering territories.

Which Ghost Towns Have the Most Accessible Archaeological Excavation Opportunities?

With $38 million in gold production history, Bodie offers the most accessible archaeological preservation, while Stonewall Mine’s GPR-enabled excavation techniques provide hands-on research opportunities you’ll appreciate. Sunrise’s prehistoric layers present unique excavation potential.

What Environmental Remediation Challenges Do Former Mining Towns Face Today?

You’ll face soil contamination from heavy metals, water pollution through acid mine drainage, costly remediation requiring multimillion-dollar investments, jurisdictional complexities due to mixed ownership, and climate change amplifying contamination through floods and wildfires.

References

- https://www.loveexploring.com/gallerylist/67994/americas-eeriest-gold-rush-ghost-towns

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://patch.com/california/banning-beaumont/13-ghost-towns-explore-california

- https://www.visitcalifornia.com/road-trips/ghost-towns/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/itineraries/the-wildest-west

- https://californiahighsierra.com/trips/explore-ghost-towns-of-the-high-sierra/

- https://asyaolson.com/the-best-gold-rush-ghost-towns-in-california/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Mining_communities_of_the_California_Gold_Rush

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowTopic-g28926-i29-k14741167-Gold_Rush_Ghost_Towns-California.html

- https://www.bodiehistory.com