Old West ghost town architecture is uniquely characterized by false front facades that create an illusion of grandeur while concealing simple structures behind. You’ll notice the stark contrast between ornate Victorian-inspired storefronts and practical, rectangular buildings. This architectural dualism reflects boom-and-bust economics, with vibrant painted decorations and gradual shifts from wood to brick construction. Preserved in a state of “arrested decay,” these structures tell compelling stories of frontier ambition, economic fragility, and the theatrical nature of Western settlement.

Key Takeaways

- False front architecture creates an illusion of grandeur with tall façades extending above actual rooflines to suggest permanence and prosperity.

- Architectural dualism contrasts theatrical urban façades with simple, practical structures behind them.

- Victorian influences bring ornate details and vibrant color schemes despite harsh frontier conditions.

- Buildings reflect boom-and-bust economics with hasty construction, attempts at permanence, and eventual abandonment.

- Main streets organized commercial and social activities with layouts following natural terrain rather than rigid grids.

The Illusion of Grandeur: False Front Design Elements

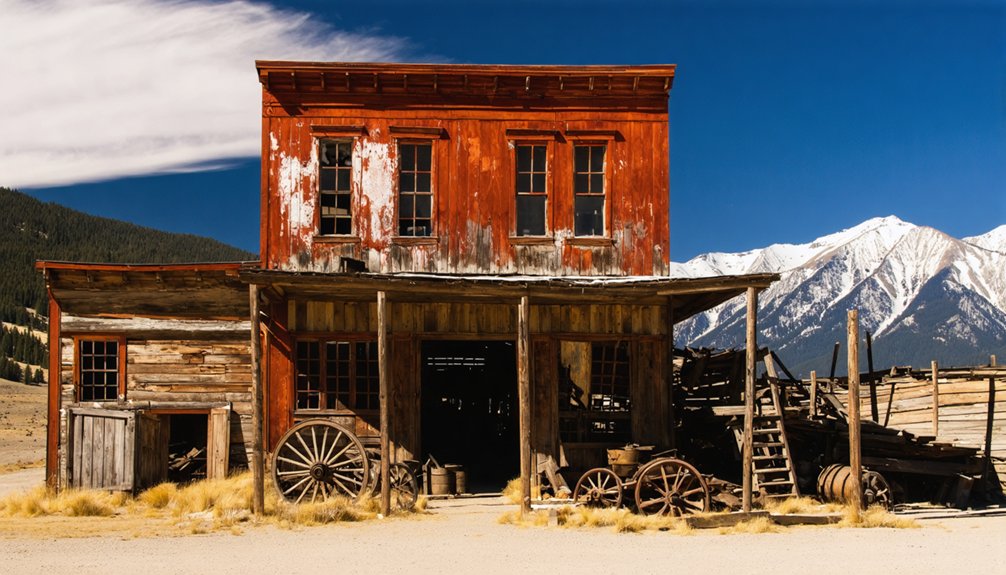

Deception stands as the fundamental principle behind false front architecture in Old West ghost towns. You’ll recognize these buildings by their tall, imposing façades that extend well above the actual roofline, creating architectural deception that masks humble structures behind.

Parapets conceal simple gable roofs while projecting the rectangular profiles of eastern urban buildings—suggesting permanence where transience reigned.

The frontier’s grand deception: eastern elegance masking western impermanence through architectural sleight of hand.

This visual storytelling concentrated ornamental details exclusively on the façade: elaborate cornices, decorative brackets, and refined window trims that contrasted sharply with the structure’s plain sides and rear.

The front served dual purposes—projecting commercial success while functioning as prominent signboards. The higher quality materials were deliberately used on the façade compared to the sides or rear of these buildings. These striking frontages typically reached 25-35 feet in height for two-story structures, commanding attention on the main street. Through this selective application of materials and craftsmanship, even modest businesses could present an illusion of prosperity and importance, despite the uncertain future of frontier towns.

Behind the Façade: Simple Structures With Elaborate Faces

While facades presented a theatrical urban sophistication to main streets across the frontier, the structural reality behind these decorative masks reveals a stark architectural dualism.

You’ll find these buildings employed functional aesthetics in their most fundamental form—simple rectangular plans with gable roofs hidden by extended parapets, creating an architectural deception that transformed humble structures into seemingly imposing commercial establishments.

This dichotomy manifested materially as well. Facades featured fine milled lumber and ornamental details, while sides and rear walls utilized rougher, cheaper materials like rough-sawn timber or adobe.

The contrast between elaborate street-facing elevations and plainly functional sides wasn’t merely economic—it represented the frontier’s aspirational character.

Buildings typically contained basic one- or two-room layouts with minimal interior partitioning, prioritizing commercial visibility over structural grandeur, maintaining the illusion of prosperity without the expense of thorough construction. In places like Bodie, California, the arid climate of the American West has helped to preserve these structures without the overgrowth that often obscures ghost towns in more humid regions. Modern recreations often feature distinctive jail and store facades positioned on opposite sides to represent the essential social institutions of frontier settlements.

Victorian Influence on Frontier Buildings

When you examine frontier Victorian architecture, you’ll notice ornate facades constructed despite harsh conditions, displaying elaborate millwork, decorative brackets, and multi-textured surfaces.

These buildings typically featured vibrant color schemes with contrasting trim work that emphasized architectural details, a practice enabled by the availability of manufactured paints transported via expanding rail networks. The influence of Andrew Jackson Downing’s popular works like Cottage Residences helped spread these architectural trends to remote Western settlements. Queen Anne style became particularly prominent in more established Western towns, characterized by sculptural shapes and elaborate ornamentation.

The importation of Eastern architectural elements—mansard roofs, bay windows, and decorative turrets—onto simple frontier structures created a fascinating juxtaposition where Victorian elegance met practical Western building methods.

Ornate Facades Despite Conditions

The contrast between harsh frontier conditions and elaborate Victorian architecture defines the peculiar aesthetic of Old West ghost towns. You’ll find buildings boasting ornate entrances and decorative moldings despite the limited resources available to frontier builders.

These Victorian embellishments weren’t mere vanity—they represented prosperity and cultural sophistication in newly established settlements. Stick Style and Queen Anne influences manifested in complex rooflines, spindlework, and patterned shingles that adorned even simple wooden structures. In Leadville, Colorado, visitors can still admire impressive examples of Victorian-era buildings preserved from the town’s mining heyday.

False fronts created imposing street presences for modest buildings, while balconies and upper walkways added vertical interest and functionality.

Merchants and saloon owners particularly embraced these ornamental touches, understanding that architectural grandeur could attract customers. The town’s banks often featured the most elaborate designs, as their ornate buildings were essential for establishing trust among potential customers and community members. The juxtaposition of rough-hewn practicality with Victorian elegance remains a compelling reminder of how frontier communities balanced survival with aspirational identity.

Colorful Painted Decorations

Victorian sensibilities transformed the rugged frontier through vibrant painted decorations that contradicted the harsh desert surroundings of Old West settlements.

These painted motifs featured rich earth tones, forest greens, and bright yellows derived from both natural pigments and emerging synthetic dyes of the late 19th century.

You’ll notice color symbolism embedded in these designs—reds and golds for saloons, intricate scrollwork for upscale establishments—communicating business function and status.

Contrasting trim highlighted architectural elements while false fronts utilized multi-tone schemes to exaggerate height and grandeur.

This architectural style differs dramatically from the stark, utilitarian designs seen in later boomtowns like Shirley Basin where false front façades gave way to modernist plainness lacking decorative charm.

Oil-based and milk paints were applied using brushes and stencils by local or traveling artisans.

These Victorian-inspired decorative elements served dual purposes: they connected remote outposts to eastern cultural norms while softening frontier harshness, blending refinement with raw survivalism in a distinctly American architectural expression.

In Goldfield, Nevada, the opulent 1908 Goldfield Hotel exemplified this aesthetic with its crystal chandeliers and mahogany furnishings that brought Eastern luxury to the Nevada desert.

Eastern Elegance Meets Frontier

Beyond the colorful painted decorations that adorned Old West buildings, a deeper architectural influence shaped frontier settlements through distinctly Victorian sensibilities.

You’ll recognize Victorian adaptations in the ubiquitous false fronts extending above actual rooflines—practical illusions of permanence that maximized signage space while concealing rudimentary construction.

Eastern influences manifested in simplified Queen Anne and Stick Style elements, with their characteristic stickwork and structural expressionism adapted to frontier limitations. Single-wall construction merged Victorian decorative brackets and finials with practical frontier economics.

Settlers brought architectural knowledge westward, establishing more formal public buildings that contrasted with initial temporary structures.

Cast-iron storefronts and imported millwork connected isolated frontier communities to established Eastern cities. These architectural choices weren’t merely aesthetic—they represented frontier dwellers’ determination to create civilization amidst wilderness while maintaining their individualistic freedom.

The Evolution From Wood to Brick: Material Transitions

You’ll find evidence of frontier pragmatism in the changeover from wooden structures to brick edifices, as mining settlements evolved from temporary camps to established towns.

This material shift wasn’t merely aesthetic but represented adaptations to harsh environmental conditions, with brick providing superior protection against fire and extreme weather that plagued wooden buildings.

The architectural metamorphosis also signaled economic maturation, as improved transportation networks enabled the importation of heavier materials and communities invested in construction that projected permanence and prosperity.

Necessity Driving Innovation

As frontier settlements rapidly transformed from makeshift camps to established communities, necessity became the primary catalyst for architectural innovation in Old West towns.

You’ll notice how practical challenges drove the evolution from expedient wood construction to more permanent materials. Fire hazards in densely packed wooden structures necessitated the shift to brick, while harsh frontier conditions demanded buildings that could withstand extreme weather.

The necessity driving these changes wasn’t merely functional—it reflected economic maturation. As mining operations stabilized, communities invested in architectural innovation that signaled permanence and prosperity.

Railroad expansion further facilitated this shift by making heavier building materials accessible to remote locations. This material evolution represented more than structural improvement; it embodied the community’s aspiration to transcend its boom-town origins and establish lasting foundations in the untamed West.

Durability Against Frontier Elements

Three distinct material shifts marked the evolution from wood to brick construction in Old West ghost towns, each responding directly to frontier survival challenges.

Initially, wood structures with false fronts dominated the landscape due to timber’s accessibility and transportability, despite their vulnerability to frontier elements.

The second phase introduced brick’s weather resilience when town prosperity permitted, offering superior insulation against temperature extremes and protection from wind erosion.

Finally, adaptive maintenance techniques emerged, including lime washes and corrugated metal roofing that extended brick longevity while preserving the characteristic Western aesthetic.

This architectural evolution wasn’t merely aesthetic—it represented pragmatic responses to harsh conditions.

Brick’s fire-resistant properties protected investments in densely built settlements, while its structural integrity withstood seasonal weather variations that rapidly degraded wooden alternatives, ensuring some structures would survive long enough to become the ghost towns we explore today.

Main Street Composition: How Towns Were Arranged

Main streets in Old West ghost towns functioned as the central nervous system of frontier settlements, organizing commercial and social activities along a primary thoroughfare.

The Main street layout typically followed natural terrain contours rather than rigid grids, with unpaved surfaces accommodating horse and wagon traffic.

Commercial clustering dominated these arteries, with buildings featuring false fronts and unified façades that created visual cohesion despite rapid construction.

False fronts united the hurriedly-built business district, creating a cohesive visual identity along bustling frontier thoroughfares.

Residential positioning kept dwellings behind or beyond the business corridor, maintaining functional separation.

Natural boundaries like rivers or hillsides often defined town limits, constraining development patterns.

Civic buildings placement reflected pragmatic priorities—prominent but secondary to commercial enterprises.

When you examine these ghost towns today, you’re witnessing practical, adaptable design that responded to economic booms and busts while maximizing limited frontier resources.

Saloons, Jails, and Hotels: Key Building Types

Saloons, jails, and hotels formed the architectural backbone of Old West settlements, each structure serving specific economic and social functions while sharing common construction principles.

False front facades dominated saloon architecture, extending modest wooden structures while displaying ornamental details that signaled business success.

Jail design prioritized security through fortified construction and robust materials, with compact layouts prominently positioned for law enforcement accessibility.

These utilitarian structures lacked the decorative elements found in commercial buildings.

Hotels featured characteristic columned porches and multi-story designs that accommodated rooms above street-level commerce.

Their wooden facades concentrated ornamentation hierarchically, with more elaborate detailing on front-facing walls.

All three building types reflected practical frontier economics—premium materials adorned visible facades while economical construction methods were applied to less prominent sections, creating the distinctive visual character we associate with Western settlements.

Ornamental Details That Told Stories of Success

In Old West ghost towns, you’ll notice elaborate parapet extensions that created imposing silhouettes against the sky, visually declaring a business’s significance and permanence.

Colorful Victorian flourishes, including ornamental brackets and intricately carved woodwork, weren’t merely decorative but served as strategic investments in public perception that communicated commercial success.

Symbolic facade elements, from custom signage to material contrasts between front and side walls, told sophisticated narratives of aspiration and achievement that resonated with both customers and competitors in frontier economies.

Elaborate Parapet Extensions

Among the most distinctive features of Old West commercial architecture, elaborate parapet extensions served both functional and symbolic purposes in frontier towns. You’ll notice these tall façades concealing simple gable roofs while creating an imposing street presence, visually enhancing modest one-story structures.

These parapets weren’t merely decorative; they embodied architectural storytelling through ornamental symbolism. Business owners projected success through columns, blind arches, and stylized moldings reminiscent of eastern establishments.

The non-structural false fronts, typically constructed with higher-quality lumber than the building’s sides, allowed rapid construction while maintaining an illusion of permanence.

You’re witnessing a form of frontier marketing when examining these facades—businesses competing through visual displays of prosperity despite often unstable economic conditions. This architectural strategy legitimized enterprises in transient communities where appearance directly influenced commercial survival.

Colorful Victorian Flourishes

Victorian flourishes transformed the architectural landscape of Old West towns, serving as vibrant expressions of economic ambition and social standing. Through decorative craftsmanship, these ornamental elements communicated prosperity and permanence in frontier environments where impermanence was common.

Victorian symbolism manifested through:

- Contrasting color schemes highlighting architectural details and distinguishing businesses along commercial streets

- Scrollwork, floral patterns, and classical motifs that narrated the owner’s refinement and cultural aspirations

- Enhanced false fronts with stickwork and decorative trim creating theatrical illusions of grandeur

- Elaborate facades featuring stained glass, patterned shingles, and cast-iron elements that attracted customers

These embellishments weren’t mere decoration—they functioned as visual storytelling devices, transforming simple wooden structures into statements of achievement and stability.

Ultimately, they created the distinctive streetscapes that define preserved ghost towns today.

Symbolic Facade Elements

Five distinct architectural elements transformed simple frontier buildings into symbols of success through their ornamental facades.

False fronts projecting above rooflines created imposing commercial presences, concealing humble structures beneath while mimicking established eastern urban architecture.

Storefront signage incorporated symbolic motifs—mining tools, cattle brands—that visually narrated economic prosperity narratives.

Decorative cornices, scrollwork, and clapboard siding demonstrated investment and craftsmanship, their facade meanings explicitly conveying business legitimacy.

Two-story mixed-use designs positioned living quarters above commercial spaces, reinforcing entrepreneurial stability through vertical integration of family and commerce.

Finally, ornamental details like carved wooden panels and painted murals served as testimonials to proprietors’ aspirations, utilizing higher-grade materials at the building front to strategically project trustworthiness to customers and investors in these speculative frontier towns.

The Role of Signage and Color in Commercial Appeal

The commercial architecture of Old West ghost towns leveraged strategic signage and deliberate color choices to establish a distinctive visual identity that could attract business in competitive frontier economies.

In frontier boom towns, visual distinction wasn’t just aesthetic—it was economic survival through strategic design.

Examining these ghost towns, you’ll notice signage evolution reflecting both practical needs and artistic craftsmanship, with skilled “wall dogs” creating durable advertisements that withstood harsh conditions.

Color symbolism played a vital role in commercial buildings’ appeal:

- Contrasting colors cut through dusty landscapes, making businesses visible from greater distances

- Strategic placement on narrow frontages maximized limited taxable space

- Layered signage tells the story of economic shifts as businesses changed hands

- Integration with architecture created landmark identifiers that served both commercial and social functions

These visual elements transformed simple wooden structures into commercial hubs that defined the frontier marketplace.

How Ghost Towns Reflect Boom-and-Bust Economics

Walking through the weathered remnants of Old West ghost towns, you’ll witness architectural embodiments of America’s boom-and-bust economic cycles that defined frontier development during the late 19th century.

These settlements materialize economic fragility through their physical structures—hastily constructed wooden buildings later replaced by brick during prosperity, then abandoned when resource extraction became unprofitable.

The urban morphology reveals demographic shifts: main streets lined with commercial establishments suddenly vacated when commodity prices plummeted.

You can trace the town’s lifecycle in its infrastructure: sturdy banks built during silver booms stand adjacent to collapsed miners’ quarters.

When mineral veins depleted or market forces shifted, these single-industry economies collapsed virtually overnight.

Buildings were often cannibalized for materials as populations fled, leaving behind skeletal frameworks that document the brutal efficiency of capitalism in America’s westward expansion.

Preserved in Time: The State of “Arrested Decay”

Within the preservation spectrum of historic sites, “arrested decay” stands as a uniquely powerful conservation philosophy that intentionally maintains ghost towns in their partially deteriorated state rather than fully restoring them to pristine condition.

This approach, pioneered at California’s Bodie State Historic Park, exemplifies preservation techniques that prioritize historical authenticity over reconstruction.

The arrested decay methodology offers visitors unparalleled insights through:

Visitors encounter authentic history suspended in time—deterioration itself becomes a powerful storyteller.

- Structural stabilization that prevents collapse while allowing existing deterioration to remain visible

- Interiors preserved with original furnishings exactly as residents left them

- Minimal interventions limited to essential repairs using period-appropriate materials

- Retention of weather damage and aging as integral parts of the historical narrative

You’re experiencing history in its raw, unvarnished form—a deliberate choice that conveys the genuine passage of time rather than a sanitized interpretation.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Climate Affect Ghost Town Architectural Adaptations?

Like canaries in a coal mine, ghost towns showcase adaptations to environmental challenges through drought-resistant water systems, flood-resistant foundations, and locally sourced climate materials that you’ll recognize as responses to harsh conditions.

Were There Cultural Differences in Native American and Settler Building Designs?

You’ll find stark contrasts between settler materials—industrialized lumber and nails—versus native designs emphasizing local, natural elements that reflected communal values and spiritual relationships with the environment they inhabited.

How Did Architects Source Building Plans in Remote Frontier Towns?

Ever wonder about frontier architectural inspiration? You’d typically source building plans through pattern books, mail-order catalogs, railroad-transported materials, and local craftsmen’s knowledge—adapting designs based on available frontier resources and practical necessities.

What Security Features Were Integrated Into Old West Buildings?

You’d find fortified structures with thick wooden walls, barred windows, and reinforced doors. Security measures included false fronts, elevated porches, strategic sightlines, and hidden compartments—all enabling autonomous protection in lawless frontier environments.

How Did Ghost Town Architecture Differ Across Various Western Territories?

Like scrolling through Instagram, you’d notice town layout varied dramatically: mining towns featured dense clusters with wooden false fronts, railroad towns stretched linearly with sturdier materials, and ethnic enclaves showcased cultural adaptations through specialized building arrangements.

References

- https://petticoatsandpistols.com/2023/02/28/old-west-architecture-and-a-giveaway/

- https://roadtripsandtinytrailers.com/2019/02/28/region-7-art-architecture-the-old-west-fun-facts/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/itineraries/the-wildest-west

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_town

- https://www.altaonline.com/dispatches/a61999061/ghost-towns-whitewashed-lauren-markham/

- https://history.howstuffworks.com/history-vs-myth/ghost-towns.htm

- https://wildwestcity.com/old-west-ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_false_front_architecture

- http://www.sierrascalemodels.com/Art_Structure.htm

- http://www.2blowhards.com/archives/2007/03/false_fronts_1.html