You’ll find Appalachian ghost towns were forgotten due to several interconnected factors in the 20th century. Many communities relied entirely on single industries like coal, which collapsed as natural gas gained prominence. Geographic isolation limited economic alternatives, while massive dam projects by the TVA physically submerged entire towns. When industries failed, residents were forced to relocate, fracturing tight-knit communities and their cultural heritage – a complex story of loss that continues to unfold across the region.

Key Takeaways

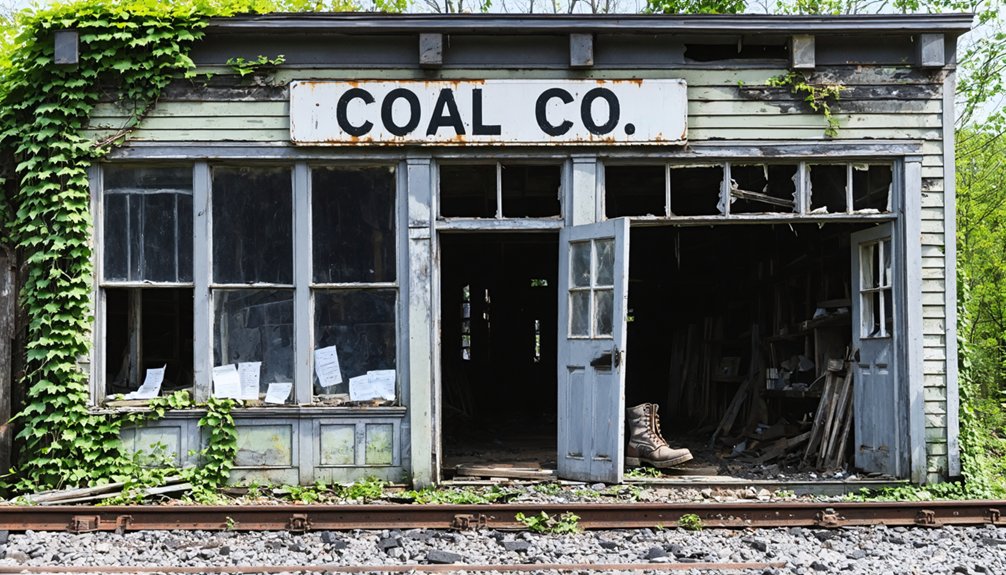

- Economic collapse of single-industry towns, particularly in coal mining, left communities unable to sustain themselves when industries declined.

- Geographic isolation limited economic diversification and access to new opportunities, accelerating community abandonment as industries failed.

- Dam construction projects in the 1940s submerged entire communities, forcing relocation and permanently erasing historical sites.

- Loss of community institutions and dispersal of populations broke cultural transmission chains, weakening historical memory.

- Limited resources for preservation efforts, combined with jurisdictional complexities and incomplete documentation, hinder ghost town conservation.

The Rise and Fall of Single-Industry Economies

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Appalachian communities emerged as distinctly vulnerable economic entities due to their reliance on single dominant industries like coal mining, textiles, and lumber production.

You’ll find that this single industry vulnerability left these towns exposed to devastating market shifts and resource depletion, as their entire economic framework depended on one sector’s success.

When you examine the structure of these communities, you’ll see how companies controlled not just employment but entire towns – from housing to stores to basic services. Workers often received company scrip as payment instead of actual wages, trapping them in a cycle of dependency.

The Great Depression in the 1930s accelerated the decline of these communities as companies reduced their workforce and cut support for town amenities.

This tight corporate grip, combined with economic volatility, meant that any industry downturn could trigger a community’s collapse.

As deindustrialization and globalization took hold in the mid-20th century, many towns couldn’t survive the loss of manufacturing and extraction jobs, leading to their abandonment.

Geographic Isolation’s Role in Town Abandonment

While the rugged beauty of Appalachia’s mountain ridges and valleys attracted early settlers, these same geographic features ultimately contributed to the region’s economic fragility and subsequent ghost towns.

Geographic barriers created a double-edged sword of cultural insularity that both strengthened community bonds and limited economic options.

These communities maintained unique local traditions as their relative seclusion from outside influence helped preserve cultural practices.

As mining companies rapidly built infrastructure and entire towns, the isolation that once protected these communities would eventually contribute to their downfall.

When primary industries like coal mining collapsed, these isolated communities faced insurmountable challenges:

- Limited transportation routes prevented easy access to outside job markets

- Physical separation from urban centers blocked development of alternative industries

- Steep terrain made infrastructure expansion prohibitively expensive

- Geographic constraints restricted the flow of goods, services, and opportunities

The mountains that once sheltered these communities became their economic prison, trapping residents between the impossible costs of relocation and the reality of vanishing local employment, ultimately leading to widespread town abandonment.

Impact of Dam Construction and Reservoir Creation

You’ll discover that several Appalachian communities, including Proctor, Fontana, and Bushnell, now rest permanently beneath the waters of Fontana Lake following the Tennessee Valley Authority’s dam construction in the 1940s.

The federal government’s prioritization of wartime power needs and flood control led to the forced relocation of hundreds of residents, who lost their homes, businesses, and access to family cemeteries. The Pearl Harbor bombing in 1941 accelerated the need for increased electricity production to support the war effort.

While promises of new infrastructure went largely unfulfilled, these submerged towns represent a profound example of how hydroelectric projects permanently altered Appalachian landscapes and communities. With many dams now over a century old, the struggle to identify clear ownership records continues to complicate modern efforts to address safety and removal concerns.

Underwater Communities Forever Lost

During the mid-20th century, numerous Appalachian communities vanished beneath artificially created lakes and reservoirs as the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers implemented massive dam projects.

You’ll find these submerged memories scattered across lakes like Fontana, Summersville, Watauga, and Jocassee, where entire towns now rest in watery graves. The construction of Chickamauga Dam alone displaced about 2,000 families from their homes. One such community was Proctor, North Carolina, which was flooded to create Lake Fontana in 1944.

These underwater communities were sacrificed for:

- Hydroelectric power generation during WWII

- Flood control infrastructure

- Regional economic development

- Creation of recreational areas

The legacy of these submerged towns lives on through underwater archaeology, with divers occasionally exploring standing forests in Lake Jocassee and building foundations visible during drawdowns.

While the reservoirs now serve millions with power and recreation, they represent a profound loss for thousands of displaced families who were forced to abandon their ancestral lands and relocate their loved ones’ graves.

Lives Uprooted By Progress

As the TVA and Army Corps of Engineers pursued their ambitious dam projects across Appalachia, thousands of families faced devastating upheaval from their ancestral lands.

You’d have witnessed entire communities torn apart as the construction of dams like Fontana and Fishtrap forced residents from homes their families had occupied for generations.

Despite promises of new roads and continued access to family cemeteries, you’d find these commitments largely unfulfilled.

The government’s pledges of infrastructure improvements proved hollow, with projects like the infamous “Road to Nowhere” abandoned after minimal construction.

The massive undertaking required relocating 1,311 families from their homes to make way for Fontana Dam’s construction and reservoir.

Community resilience was tested as traditional livelihoods disappeared beneath rising waters, while cultural regeneration proved challenging in unfamiliar locations.

The displacement destroyed not just physical structures but also the intricate social fabric that had defined these mountain communities for centuries.

The construction of Fontana Dam served a crucial wartime purpose, providing hydroelectric power to the Oak Ridge facility during World War II.

The Cultural Cost of Community Displacement

While economic decline drove the physical abandonment of Appalachian towns, the cultural toll of community displacement cut far deeper into the region’s social fabric.

You’ll find that the dispersal of tight-knit communities fractured generations of cultural transmission and community cohesion built around shared labor, traditions, and resilience.

The closure of essential community institutions dealt devastating blows:

- Churches and schools that anchored social life fell silent

- Traditional gathering spaces for festivals and dances disappeared

- Extended family networks weakened as populations scattered

- Cultural practices and oral histories stopped being passed down

This displacement particularly impacted marginalized groups, including Indigenous peoples, Black communities, and immigrant laborers whose stories often go untold.

The result wasn’t just empty buildings – it was the unraveling of complex social bonds that had sustained Appalachian culture for generations.

When Natural Resources Run Dry: Economic Exodus

Once natural gas began displacing coal as America’s primary energy source, Appalachian communities experienced an unprecedented economic collapse that devastated local economies and accelerated regional exodus.

You’ll find the impact of this resource depletion reflected in stark statistics: coal mining jobs plummeted by 49% between 2011 and 2018, while the Central Appalachian Basin‘s coal output crashed by 80%.

This dramatic decline triggered widespread economic migration, with coal-dependent counties losing over 5% of their population, particularly working-age adults.

You’re witnessing the ripple effects throughout these communities, as household credit scores drop and financial instability rises.

Despite attempts at economic diversification, few Appalachian counties have successfully shifted away from their coal-dependent past, leaving many towns teetering on the edge of abandonment.

The Challenge of Historical Preservation

The physical remnants of Appalachia’s coal-mining past face mounting preservation challenges that extend beyond economic decline.

Abandoned coal mines dot Appalachia’s hills, their crumbling structures bearing silent witness to a vanishing industrial heritage.

You’ll find a complex web of obstacles hindering efforts to protect these historic sites, from severe geographic barriers to critical funding limitations.

The most significant preservation challenges include:

- Remote mountainous terrain and harsh weather conditions accelerating structural deterioration

- Limited financial resources, with local historical societies struggling to maintain sites

- Jurisdictional complexities across private, state, and federal lands

- Incomplete documentation and fragmented historical records

What you’re witnessing is a race against time, as these irreplaceable pieces of American history battle natural elements and institutional hurdles.

Without coordinated preservation efforts and dedicated funding streams, many of these ghost towns risk disappearing entirely from the Appalachian landscape.

The stories of abandoned towns from the Civil War hold significant historical value. Their structures provide insight into the past, showcasing the struggles and resilience of communities that once thrived in the region. It is essential to prioritize their preservation for future generations to appreciate and learn from these remnants of history.

Hidden Beneath the Waters: Submerged History

Beneath Appalachia’s tranquil reservoir waters lies a hidden chapter of American history, where entire communities were systematically erased during ambitious dam projects of the mid-20th century.

You’ll find submerged memories of towns like Gad, Proctor, and Loyston – sacrificed for flood control and hydroelectric power. Their stories persist through aquatic archaeology, with divers documenting remnants like Attakulla Lodge in Lake Jocassee and the preserved structures of Gad beneath Summersville Lake’s clear waters.

The Tennessee Valley Authority’s documentation of Loyston stands as a rare example of thorough historical preservation, while other communities like Dutch Fork and Saxe Gotha have nearly vanished from record.

These underwater ghost towns represent more than flooded ruins – they’re evidence of communities displaced in the name of progress.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Many People Still Live in Appalachian Ghost Towns Today?

You’ll find current inhabitants ranging from zero to around ten people in most Appalachian ghost towns, though population trends vary – some maintain seasonal residents while others are completely abandoned.

What Happened to the Artifacts and Valuables Left Behind?

Like time capsules beneath murky waters, you’ll find artifacts scattered across ghost towns – some preserved in museums, others submerged by dam projects, while many were stolen or slowly reclaimed by nature’s unstoppable march.

Are There Any Successful Ghost Town Revitalization Projects?

You’ll find successful ghost town revitalization in Jerome, Arizona, where community engagement transformed a mining town into an arts hub, and Cerro Gordo, California, where private investors restore historic structures.

Do Descendants of Original Residents Still Visit These Forgotten Places?

While many assume these places are truly abandoned, you’ll find descendant reunions happening regularly, with families returning to preserve memories through storytelling, photograph sharing, and maintaining ancestral grave sites.

Can Tourists Legally Explore and Photograph These Abandoned Towns?

You’ll need to verify each site’s legal status before urban exploration, as many ghost towns have strict access restrictions. Some allow photography on public lands, while private properties require owner permission.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4oHlJFXbrCk

- https://appalachianmemories.org/2025/10/16/the-lost-towns-of-appalachia-the-forgotten-mountain-communities/

- https://www.blueridgeoutdoors.com/go-outside/southern-ghost-towns/

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.thewanderingappalachian.com/post/the-underwater-towns-of-appalachia

- https://smokymountainnationalpark.com/blog/fun-facts-about-elkmont-ghost-town/

- https://www.100daysinappalachia.com/2021/09/commentary-appalachia-can-prove-company-towns-dont-lift-the-working-class/

- https://www.appalachianplaces.org/post/appalachia-s-other-company-towns

- https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q3_economic_history

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A0GJGfJJOwI