Wilford, Arizona was established in 1883 as a Mormon settlement originally called Adam’s Valley. You’ll find this ghost town in Navajo County, where it flourished briefly before environmental challenges, including poor soil and devastating floods, took their toll. The Anti-Polygamy Edmunds Act forced many residents to flee to Mexico in the 1880s. By 1889, the community ceased to function, leaving only scattered stone foundations that you can explore today. Its barren landscape tells a deeper story.

Key Takeaways

- Wilford was established in 1883 as a Mormon settlement, originally called Adam’s Valley, led by Bishop Hans Hansen.

- The town declined rapidly after the 1885 Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act, with nearly half the population fleeing to Mexico.

- Environmental challenges including poor soil, flooding, and the 1887 earthquake contributed significantly to Wilford’s abandonment.

- By 1889, Wilford ceased functioning as a community, with the final recorded inhabitation occurring in 1926.

- Today, only scattered stone foundations remain, requiring foot travel to navigate the undeveloped ghost town site.

The Mormon Settlement of Adam’s Valley (1883)

While many ghost towns in Arizona have their roots in mining booms, Wilford began as part of a systematic Mormon colonization effort in 1883. When the Brigham City settlement failed, Jerome Jefferson Adams and several other Mormon families relocated to establish a new community about seven miles south of present-day Heber.

Initially named Adam’s Valley after its founder, the settlement was renamed Wilford that August. This community exemplified Mormon heritage through its structured organization under church leadership.

The Mormon settlers’ cultural identity shaped Wilford, transforming Adam’s Valley into a structured religious community under ecclesiastical governance.

By 1884, an LDS ward was established with Bishop Hans Hansen traveling by mule across the extensive territory to minister to the faithful. The community later suffered significant demographic decline when nearly half its population left due to the Anti-Polygamy Edmunds Act.

The settlement represented community cohesion through shared religious practices, despite lacking a central meeting place. Families maintained their agrarian traditions, focusing on livestock raising and small-scale farming. Like other Mormon settlements along the Little Colorado River, Wilford residents kept detailed diaries and journals documenting their pioneer experiences.

Environmental Struggles in a Harsh Frontier

You’ll find Wilford’s settlers immediately struggled with the area’s sandy, salty soil that proved nearly impossible for sustaining crops.

Flash floods repeatedly destroyed dams and irrigation systems, while early frosts damaged what little could grow in the poor conditions.

The town experienced a brief boom period when mining operations attracted workers, but ultimately declined as resources were depleted. Like many Arizona ghost towns, Wilford was eventually abandoned due to economic decline and environmental challenges.

Sandy, Salty Soil

Settlers of Wilford confronted some of Arizona’s most challenging soil conditions, making agriculture and construction extraordinarily difficult in this frontier outpost.

You’d have found the ground beneath your feet dominated by Casa Grande series soils—saline-sodic compositions that created alkaline, inhospitable growing conditions. These sandy, salty soils contained high concentrations of sodium and calcium, preventing most crops from thriving without extensive amendments.

The hyperthermic arid classification of Wilford’s terrain meant you’d experience rapid soil erosion during rare but intense rainfall events. This soil type caused more annual damage to structures than floods, tornadoes, and hurricanes combined in similar regions.

Structures you built would have suffered from the land’s tendency toward hydrocompaction, where seemingly stable ground suddenly collapsed when wetted. Like many mining towns of Arizona, Wilford’s infrastructure deteriorated rapidly as buildings succumbed to the harsh environmental conditions. Foundations cracked as the shrink/swell cycle repeatedly expanded and contracted the clay-rich portions of the soil, gradually destroying buildings and making permanent settlement a constant struggle.

Recurring Natural Disasters

As Wilford struggled with its challenging soil conditions, a series of punishing natural disasters repeatedly threatened the town’s survival throughout its brief existence.

You’d have witnessed devastating floods along the San Pedro River that destroyed vital mining infrastructure, bridges, and roads, effectively isolating the community and disrupting ore processing essential for economic survival.

The catastrophic 1887 earthquake, with aftershocks lasting over 30 minutes, further devastated mining operations in Wilford and neighboring settlements.

Meanwhile, recurring drought cycles created chronic water scarcity that hindered ore refinement processes and increased operational costs. The mills that once operated twenty-four hours daily were forced to reduce production due to these environmental challenges. Residents created detailed death maps to document the concerning patterns of illness and mortality that plagued their community.

These natural disasters compounded the mining impacts already plaguing the region—radioactive contamination from uranium mining and heavy metal leaching from unprotected waste piles continued to degrade soil and water quality long after the town’s abandonment.

Overgrazing Damages Land

The verdant grasslands surrounding Wilford transformed into barren wasteland through relentless overgrazing that began in the 1880s. By 1888, the environmental impacts became devastating as Aztec Land & Cattle Company and competing operations flooded the San Pedro Valley with unsustainable herds.

Overgrazing impacts accelerated Wilford’s demise:

- Native vegetation disappeared, triggering rapid soil erosion and eliminating agricultural potential.

- Water sources became contaminated with cattle carcasses during droughts, requiring filtration.

- Massive die-offs (50-75% mortality) devastated ranching operations economically.

- Desertification processes permanently altered the ecosystem, preventing recovery.

This land degradation ultimately forced economic collapse. Government policies of the era actively favored aggressive overstocking, encouraging ranchers to maximize herd size despite clear ecological warning signs. As carrying capacity plummeted, ranchers abandoned their operations and relocated.

The environmental devastation preceded Wilford’s complete abandonment in 1926, proving the frontier’s harsh limits on unchecked exploitation.

Impact of the Anti-Polygamy Edmunds Act

You’ll find the Edmunds Act of 1882 sparked a significant southern exodus from Wilford as polygamous families fled to Mexico to escape federal prosecution and the possibility of five-year prison sentences. The federal law explicitly defined polygamy as a felony offense, making it impossible for these families to maintain their lifestyle in Arizona.

This demographic shift hollowed out the once-thriving community, leaving behind abandoned homesteads and fragmenting the social fabric that had held the settlement together.

Southern Exodus Begins

Following passage of the Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act in 1882, Mormon settlements across Arizona Territory faced unprecedented legal pressure that triggered what became known as the Southern Exodus.

This migration represented a desperate bid for religious liberty as federal officials aggressively prosecuted polygamists under the new law’s “unlawful cohabitation” provisions.

The southern migration dramatically altered settlement patterns as families fled south to avoid prosecution:

- Federal marshals targeted Mormon households with fines up to $300 and six-month prison terms

- Entire communities relocated after losing voting and jury service rights

- Church leadership encouraged migration after courts rejected defenses based on discontinued marital relations

- The exodus accelerated following Secretary Evarts’ 1879 circular restricting immigration of polygamous believers

You’ll find that many Wilford residents abandoned their homes during this tumultuous period, seeking freedom beyond federal reach.

Demographic Consequences Unfold

Demographic shifts from the Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act rippled through Wilford’s social fabric almost immediately after its 1883 founding.

You’d have witnessed the progressive erosion of this Latter-day Saint community as federal pressure forced brethren to flee imprisonment on polygamy charges.

The settlement’s population declined steadily throughout the mid-1880s and 1890s. With each departure, Wilford lost crucial labor capacity and communal strength.

Community fragmentation accelerated as leadership couldn’t maintain cohesion under intensifying legal threats.

Meanwhile, local cowboys exploited these vulnerabilities, mounting intimidation campaigns against remaining settlers.

These combined pressures – federal prosecution, economic decline, and frontier hostility – created a demographic spiral from which Wilford couldn’t recover.

The settlement’s social foundation collapsed years before its official abandonment in 1926, leaving only scattered stone remnants of a once-vibrant community.

When Cowboys Replaced Pioneers

As Arizona Territory developed beyond its earliest frontier days, a distinctive change occurred when ranching families like the Haydens moved from Missouri to Arizona in 1886, transforming the pioneer lifestyle into cattle country.

You’d notice these cowboys managing hundreds of cattle, adapting to natural challenges like the devastating 1891 flood that forced many to relocate.

This evolution from pioneer to cowboy culture included:

- Multi-role adaptation – combining farming, freighting, and trading for survival

- Large-scale ranching operations replacing smaller homesteading efforts

- Economic diversification when facing industrial pressures like Motorola’s growth

- International expansion, with some ranchers venturing into ventures like Australian cotton farming

This alteration wasn’t merely occupational – it represented Arizona’s maturation from raw frontier settlements to established ranching communities, forever changing the territorial landscape.

The Final Years: Abandonment and Dissolution

While flash flooding destroyed critical dams and irrigation systems in the early 1880s, it was the 1885 Edmunds Act that delivered the fatal blow to Wilford’s future.

Nearly half the population fled to Mexico to escape anti-polygamy enforcement, devastating community resilience. By 1888-1889, most remaining families departed as overgrazing accelerated environmental degradation.

The economic transformation from sustainable farming to cattle ranching proved disastrous under local conditions. Hashknife Cowboys brought social tensions rather than stability, pushing out the few lingering residents.

Though technically inhabited by scattered ranchers until 1926, Wilford effectively ceased functioning as a community by 1889.

Today, only loose rock foundations remain where this Mormon settlement once stood—a stark reminder of how quickly a community can vanish when faced with combined legal, environmental and social pressures.

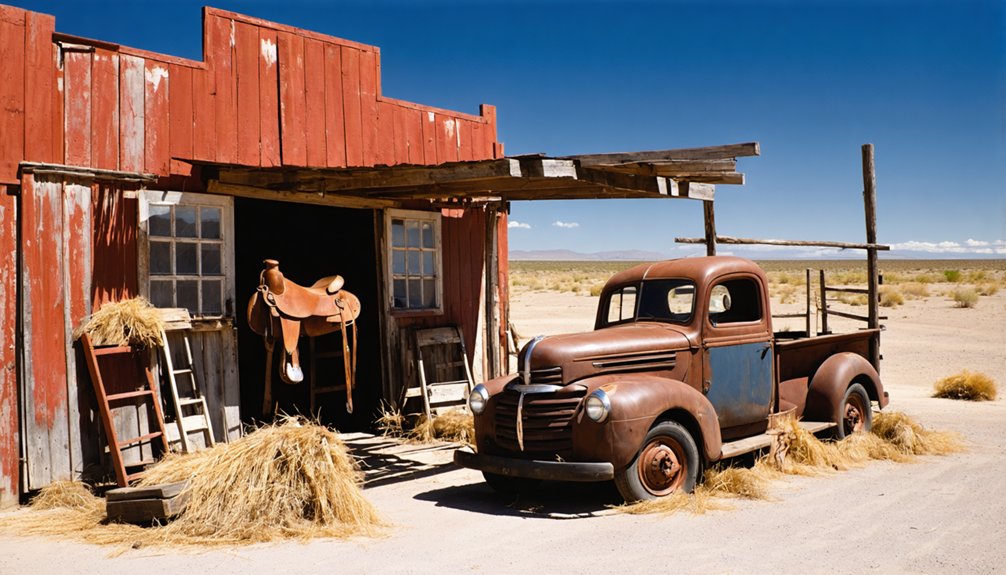

What Remains Today: Exploring Wilford’s Ghost Site

Where once a thriving Mormon settlement stood in Navajo County, today’s visitors to Wilford will find little more than scattered stone foundations and barren desert landscape.

These ghostly remnants contrast sharply with other Navajo County ghost towns like Sunset and Zeniff, which maintain more visible structures and markers of their past.

If you’re planning to explore Wilford’s historical significance, expect:

- Only loose rock foundations marking former building locations

- Undeveloped terrain requiring foot travel to navigate the site

- No standing structures, interpretive signs, or maintained pathways

- A stark visual lesson in environmental degradation from overgrazing

The abandoned site, last occupied in 1926, now serves as physical evidence of Mormon settlement patterns and illustrates how socio-political forces and environmental mismanagement can lead to a community’s complete dissolution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous People Born in Wilford Before Abandonment?

No famous people or historical figures were born in Wilford during its short existence. You won’t find any notable individuals in the records before the settlement’s abandonment in 1926.

What Happened to Jerome Adams After Wilford’s Decline?

You won’t find documented evidence of Jerome Adams’ life changes after Wilford’s decline. His historical impact remains limited to founding the town, with no verified records of his subsequent activities.

Are There Accessible Ruins or Artifacts From Wilford Today?

Virtually nothing remains for ghost town exploration at Wilford today. You’ll find only scattered stone foundations—no standing structures or accessible artifacts. The site’s barren condition offers little beyond minimal rock rubble.

Did Any Wilford Families Return After Initially Leaving?

You’ll find no clear evidence that Wilford families returned permanently. Historical records show gaps about return motivations, though some relocated nearby to Heber rather than Mexico, maintaining regional ties.

Were Any Films or Books Created About Wilford’s History?

Ever wonder what remains of forgotten places? You’ll find Wilford mentioned briefly in ghost town compilations and Mormon settlement books, but no dedicated Wilford documentaries or standalone Wilford literature exist chronicling its short-lived history.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Arizona

- https://azgw.org/navajo/ghosttowns.html

- https://skillsetmag.com/article/where-the-west-was-won-az-ghost-towns/

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=68679

- https://www.rarenewspapers.com/list?page=56&per_page=10&q[category_id]=106&sort=items.id&sort_direction=ASC

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Wilford

- https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:80444/xv44747

- https://rsc.byu.edu/pioneer-women-arizona/appendix-1

- https://octa-trails.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Jelinek-Mormon-Settlement-of-the-Forestdale-Valley.pdf

- https://rsc.byu.edu/sites/default/files/pub_content/pdf/Appendix_1_0.pdf