Yukon began as Blackpoint Settlement, established by freed enslaved people in the mid-1800s near present-day Jacksonville. You’ll find it evolved into a bustling railroad town with 300 residents, paved streets, and diverse commerce. World War I’s Camp Johnston brought major growth until 1963, when the U.S. Navy declared it a flight safety hazard and evacuated residents. Today, you can explore its preserved grid streets as hiking trails in Tillie K. Fowler Park, where each path reveals another layer of this lost community’s story.

Key Takeaways

- Yukon was a thriving Florida community near Jacksonville that became a ghost town after the U.S. Navy declared it a flight hazard in 1963.

- Over 300 homes were demolished when residents were forced to evacuate, though some commercial structures remained standing afterward.

- The town’s demise was linked to three major aviation incidents near Naval Air Station Jacksonville in subsequent decades.

- Originally established in the mid-1800s, Yukon flourished as a rail depot and commerce hub before serving Camp Johnston during WWI.

- The former townsite is now part of Tillie K. Fowler Park, where original brick streets serve as hiking trails for visitors.

Early Days of Blackpoint Settlement

While Spanish authorities granted the land along the St. Johns River at Black Point to Timothy Hollingsworth in 1787, you wouldn’t recognize the landscape that would later become Yukon.

Early landownership centered on Mulberry Grove Plantation, where cotton fields eventually gave way to diverse crops like citrus, fruits, and vegetables shipped via river steamships.

The story of community resilience began when Arthur M. Reed, the plantation’s final owner, sold portions of his land to formerly enslaved people after the Civil War.

You’ll find this watershed moment marked the birth of Blackpoint Settlement, as freed African Americans established their own community across the railroad tracks.

They built modest homes, cultivated the land, and leveraged the St. Johns River’s transportation advantages to create new opportunities for themselves. The Navy closed Yukon in 1963, leading to the demolition of most buildings in the community. The community included the historic Mulberry Grove cemetery, which became a final resting place for both enslaved people and freedmen.

A Thriving Community Emerges

In the mid-1800s, you’d find Yukon taking shape as Blackpoint Settlement, established on land deeded to freed enslaved people after the Civil War.

The arrival of the railroad depot transformed this modest settlement into a hub of commerce, facilitating the movement of people and goods throughout the region.

The small community grew steadily, reaching a population of about three hundred residents by the time it was officially founded.

The community featured paved gridded streets and sidewalks that helped establish an organized layout for residents.

Early Pioneer Settlement Activities

During the late 18th century, Yukon’s pioneering settlement began with Timothy Hollingsworth’s Spanish land grant at Black Point along the St. Johns River.

You’d have found the early settlers facing pioneer challenges as they transformed the wilderness into the productive Mulberry Grove Plantation, where cotton became the primary focus of cultivation.

As you’d expect from ambitious settlers seeking prosperity, they didn’t limit themselves to a single crop for long.

Settlement growth accelerated as agricultural activities expanded to include orange groves, cattle ranching, and diverse fruits and vegetables.

The plantation’s strategic location along the St. Johns River proved invaluable, as steamships carried their products to regional markets.

After the Civil War, portions of the plantation were sold to formerly enslaved people, establishing the foundational “Blackpoint Settlement” that would evolve into Yukon.

The land that would become Yukon included A.M. Reed’s plantation, which played a significant role in the area’s agricultural development.

Railroad Brings Economic Growth

As rail service reached Yukon in the late 19th century, the Jacksonville, Tampa and Key West Railway transformed this agricultural settlement into a bustling commercial hub.

Railroad expansion brought unprecedented opportunities, connecting local farmers and merchants to broader markets through an integrated network of rail and steamship routes. Like the success of the White Pass Railway, which opened remote regions to commerce in 1898, Yukon’s rail development created vital transportation corridors for growth. Given its position near the St. Johns River, the railway benefited from easy access to Jacksonville’s thriving port operations.

You’d have witnessed a remarkable economic transformation as the rail depot became the heart of commerce. Local producers efficiently shipped cotton, citrus, cattle, and vegetables to distant markets, while businesses flourished along Yukon Road.

The railway’s strategic position near Camp Johnston during World War I brought military traffic and further prosperity. The combination of agricultural shipping capabilities and military transport needs established Yukon as a crucial transportation nexus, drawing workers and entrepreneurs who built thriving commercial enterprises around the rails.

World War I and Camp Johnston’s Influence

You’ll find that Camp Johnston’s massive military training infrastructure, built in late 1917, transformed Yukon with new construction spanning over 3,000 acres and housing 27,000 soldiers.

The brick streets laid during this period remain one of the few visible traces of Yukon’s wartime development that you can still see today.

Your understanding of Yukon’s history wouldn’t be complete without recognizing how the soldiers’ presence revolutionized the local economy, as their activities and needs sparked unprecedented growth in businesses and services throughout the community.

The camp evolved into a sprawling complex with 600 military buildings, becoming a cornerstone of Army quartermaster training during World War I.

Soldiers endured harsh living conditions similar to those later faced at Camp Gordon Johnston, including basic barracks and outdoor facilities.

Military Training Infrastructure Built

The establishment of Camp Joseph E. Johnston in late 1917 brought unprecedented military training infrastructure to Northeast Florida.

You’d have found a massive 3,036-acre complex featuring between 600-825 buildings dedicated to training America’s World War I forces. The camp’s facilities included specialized barracks, training grounds, and the nation’s second-largest rifle range.

You would’ve seen extensive technical training areas where Quartermaster units prepared for overseas deployment, alongside administrative buildings and logistical support facilities.

The infrastructure supported high-volume troop mobilization, with soldiers from 20 different states training simultaneously. A YMCA center and educational facilities provided essential services during soldiers’ downtime.

The camp’s strategic design enabled the training of 27,000 men and the organization of 405 units, including 360 technical units that served overseas.

Brick Streets Remain Today

Walking through Tillie K. Fowler Park, you’ll discover the lasting brick streets of old Yukon, a remarkable demonstration to World War I-era construction.

These century-old pathways were built to handle heavy military equipment during Camp Johnston’s operations from 1917-1919, and they’ve outlasted nearly everything else from that period.

- The brick streets contrast sharply with modern asphalt roads, offering a window into early 20th-century engineering.

- Despite decades of weathering and overgrowth, the brick preservation remains impressive.

- You can trace the original town layout through these surviving pathways.

- The historical significance of these streets connects directly to Camp Johnston’s military training activities.

Though Yukon’s buildings are long gone, these durable brick thoroughfares stand as silent witnesses to the town’s crucial role in supporting America’s World War I military effort.

Soldiers Transform Local Economy

During World War I, Camp Johnston‘s massive presence transformed Jacksonville’s economic landscape, as 27,000 soldiers stationed at the sprawling 3,036-acre facility created unprecedented demand for local goods and services.

You’d have witnessed a remarkable economic boost as Jacksonville’s businesses rushed to supply the camp with food, clothing, and construction materials for its 600-plus buildings.

The military impact rippled through the community when a new trolley line opened in April 1918, connecting soldiers to downtown entertainment and commerce. Local employment soared as civilians found work supporting the massive complex’s operations.

The prosperity lasted until mid-1919, when the camp’s closure following the war’s end brought this economic surge to an abrupt halt.

Still, the brief but intense period reshaped Jacksonville’s wartime economy.

As World War II loomed on the horizon, Naval Air Station Jacksonville emerged as a cornerstone of U.S. naval aviation when it was commissioned on October 15, 1940.

The base’s rapid military expansion transformed Jacksonville into a powerhouse of wartime preparation, with three runways stretching over 6,000 feet and essential seaplane facilities along the St. Johns River.

Expansive runways and vital seaplane facilities along the St. Johns River positioned Jacksonville as a crucial military aviation hub.

You’ll find these remarkable achievements defined NAS Jacksonville’s wartime impact:

- Trained over 21,000 aviation personnel, including 10,000 pilots who earned their wings

- Built 700+ buildings, including an 80-acre hospital and POW camp housing 1,500 Germans

- Established significant aircraft maintenance facilities through NARF Jax

- Became home to the WAVES program, breaking barriers for women in military service

The station’s strategic location and thorough facilities made it indispensable to America’s Atlantic defense strategy.

Life in Yukon’s Prime Years

While Naval Air Station Jacksonville bustled with wartime activity, the adjacent town of Yukon thrived as a well-planned community with paved streets, sidewalks, and a vibrant downtown business district.

If you’d lived in Yukon during its prime, you’d find yourself part of a close-knit community where Navy families mingled with long-time residents. You could shop at local stores downtown or catch a train at the railroad depot.

The 300-unit Dewey Park subdivision offered comfortable housing for military personnel and their families. Community events and family gatherings brought neighbors together, while children attended nearby schools.

Between the St. Johns and Ortega Rivers, you’d enjoy scenic views and outdoor activities. The town’s infrastructure, including water utilities and municipal services, supported a comfortable small-town lifestyle typical of mid-20th century America.

In July 1963, the U.S. Navy issued an ultimatum that would forever change Yukon’s destiny. Due to the town’s dangerous proximity to Naval Air Station Jacksonville, officials declared the settlement a flight safety hazard and exercised eminent domain, forcing a complete Navy evacuation of residents.

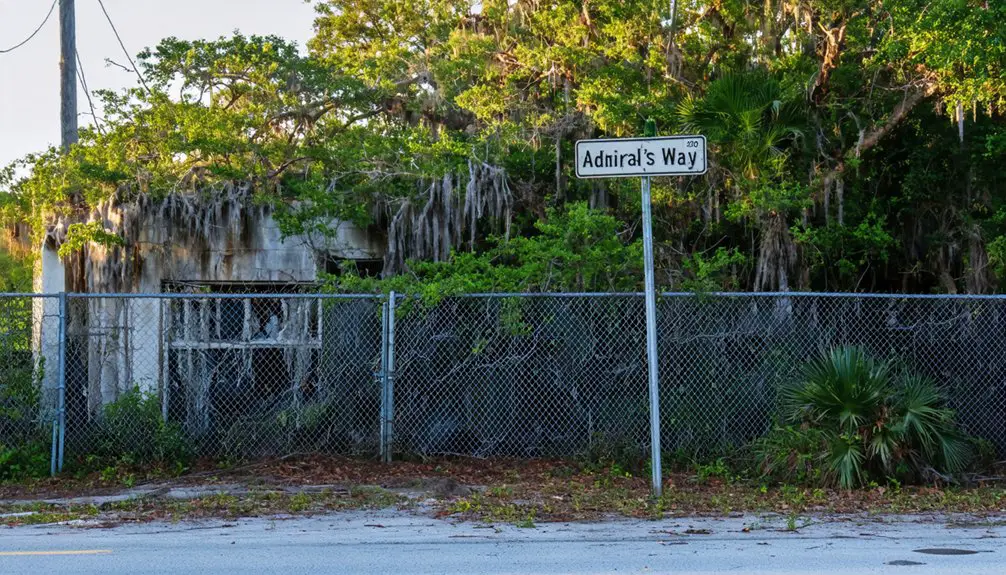

You’d find over 300 homes being systematically demolished, though most commercial structures remained.

You’ll notice the Navy’s decision proved prescient, with three major aviation incidents occurring near the area in subsequent decades.

You can still spot remnants of the railroad depot slab within what’s now Tillie K. Fowler Regional Park.

You’ll discover that while conspiracy theories circulated about secret experiments, flight safety concerns were the genuine reason for closure.

This decisive action ended Yukon’s 176-year history as an inhabited community, transforming it into today’s ghost town.

Traces of a Lost Town

Today’s visitors to Tillie K. Fowler Regional Park walk among the remnants of a once-thriving community. If you explore carefully, you’ll discover traces of Yukon’s ghost town hidden beneath the park’s natural growth – from the old railroad depot slab across from NAS Jacksonville’s main gate to the original brick streets that now form walking trails.

You can still find fragments of the town’s business district, including foundations of the Baptist church and post office. The grid of paved streets and sidewalks remains visible, though nature has reclaimed much of the landscape.

Historical markers are scarce, but the physical evidence tells the story: building foundations peek through vegetation, and the Mulberry Grove Plantation cemetery endures as a solemn reminder of the community’s diverse past.

Preserving History at Tillie K. Fowler Park

The preservation of Yukon’s heritage found new life when the City of Jacksonville leased the former townsite from the Navy in 1979.

Through community engagement and historical preservation efforts, you’ll find traces of the past carefully integrated into what’s now Tillie K. Fowler Regional Park.

- Walk the same gridded streets where Yukon’s residents once lived, now transformed into hiking trails.

- Discover the original railroad depot slab, a reflection of the town’s bustling past.

- Explore remnants of the downtown business district near Roosevelt Boulevard.

- Visit local establishments like J.L. Trent’s Seafood and Murray’s Tavern that help keep the area’s spirit alive.

While nature slowly reclaims parts of this historic settlement, the park stands as a living memorial to Yukon’s legacy, offering both recreational opportunities and historical significance for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Residents After They Were Forced to Leave?

You’ll find most residents’ relocation scattered them throughout Jacksonville’s neighboring areas, disrupting their tight-knit community. While records don’t track individual moves, the displacement tore apart their established social networks.

Proper payment patterns remain unclear from historical records. While the Navy’s land acquisition impacted your property rights, there’s no definitive evidence showing if you’d have received compensation for seized lands.

How Many Original Structures From Yukon Still Exist Today?

You’ll find only a handful of historically preserved structures today, including the Baptist Church, old post office, and some business district buildings along Roosevelt Boulevard – each retaining architectural significance despite widespread demolition.

What Was the Total Population of Yukon at Its Peak?

Time flies when you’re building a community! You’ll find that Yukon’s history shows a peak population of approximately 1,000 residents before its population decline began, leading to the town’s eventual closure in 1963.

Did Any Families From the Original Yukon Settlement Stay in Jacksonville?

You’ll find some Yukon descendants still living in Jacksonville today, though complete family records aren’t available. Many displaced residents chose to rebuild their lives in nearby Jacksonville neighborhoods.

References

- https://thecampusvoice.wordpress.com/2017/10/27/yukon-fl-jacksonvilles-ghost-town/

- http://www.gribblenation.org/2018/02/ghost-town-tuesday-yukon-fl-abandoned.html

- https://www.thejaxsonmag.com/article/ghost-town-yukon-florida/

- https://www.news4jax.com/news/2012/04/30/jacksonvilles-ghost-town-yukon/

- https://www.moderncities.com/article/2020-oct-ghost-town-yukon-florida-page-2

- https://www.thejaxsonmag.com/article/11-black-jacksonville-stories-you-probably-dont-know-page-2/

- https://jaxpsychogeo.com/west/yukon-ghost-zip-code/

- https://www.thetravel.com/why-florida-ghost-town-near-jacksonville-was-abandoned/

- https://www.metrojacksonville.com/article/2008-aug-jacksonvilles-ghost-town-yukon

- https://panhandlepioneer.org