Nebraska’s abandoned frontier towns tell poignant stories of rise and fall. You’ll find Pischelville’s preserved community hall, Ansel’s railroad-dependent remains, Venus’s social centers, Morrillville’s flood-ravaged mill town, Archer’s legally disputed settlement, Walnut’s post-office centered society, and Sparta’s historic mercantile building. Each ghost town reveals how railroad economics, government decisions, and natural disasters determined frontier survival. These seven settlements offer compelling windows into the state’s rural development and subsequent decline.

Key Takeaways

- Pischelville, established in 1858, preserves its Bohemian heritage through the community hall and National Cemetery with artistic grave markers.

- Ansel reached its peak in the 1920s before declining due to agricultural bust and dependency on railroad economics.

- Archer, founded in 1855, was abandoned by 1857 when a government resurvey nullified property rights.

- Morrillville thrived around its grain mill until repeated flooding destroyed this economic lifeline, forcing residents to relocate.

- Walnut’s decline began with the 1924 post office closure, leaving only crumbling foundations and cedar trees as remnants.

Pischelville: The River Settlement That Time Forgot

Along the winding banks of the Niobrara River in Knox County, Nebraska, lies Pischelville, a settlement whose origins trace back to 1858 when Judge T. N. Paxton first established what was then called Running Water.

Along the Niobrara’s curving shoreline sits Pischelville, a historic Nebraska settlement dating back to Running Water in 1858.

You’ll find this frontier community later took its name from Anton Pischel, a prominent leader whose legacy endures in the family cemetery south of town.

The Pischelville heritage remains visible through the community hall constructed in 1884, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

This river settlement once thrived with a blacksmith shop, saw mill, and flour mill—economic engines that sustained frontier life until the mid-20th century.

In 1870, the settlement welcomed Czech immigrant Jan Srajer, who later changed his name to John Schreier and applied his cabinet making skills to construct his family home along Steel Creek.

The area’s development mirrored other small communities like Venus that once had thriving businesses including stores, churches, and schools.

While many similar settlements vanished entirely, Pischelville’s cultural institutions, particularly its Bohemian National Cemetery with artistic grave markers, have preserved its distinct identity against the eroding forces of time.

Ansel: From Railroad Boom to Agricultural Bust

You’ll find Anselmo’s economic trajectory traced directly to the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad extension of 1886, which transformed it from isolated farmland into a vibrant commercial center.

The town of Ansley, named after a real estate investor, experienced similar growth patterns along the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad during the same period.

By the 1920s, the town had reached its zenith with numerous businesses serving farmers who could now ship their grain to distant markets via rail.

The town was originally laid out by a civil engineer named Anselmo Smith who selected town sites along the Burlington rail line.

The agricultural bust that followed, characterized by falling grain prices and farm consolidation, triggered Anselmo’s decline from boom town to abandoned settlement, exemplifying the fragile dependency many frontier towns had on railroad economics.

Railroad Hub Economics

As the transcontinental railroads stretched their steel ribbons across Nebraska in the late 19th century, they didn’t merely transport goods and people—they systematically created an economic ecosystem that would transform the frontier landscape.

Through strategic town formation, railroad companies deployed townsite agents to recruit settlers and merchants, ensuring population bases that would generate freight revenue.

This railroad expansion triggered profound economic transformation. Towns like Falls City flourished at junction points, becoming regional trade centers with competitive freight rates and specialized agricultural industries. Falls City experienced remarkable growth after the arrival of the Atchison & Nebraska Railroad in 1871, setting the stage for its development as a key transportation hub.

You’d find manufacturing operations producing farm equipment precisely where rails converged.

When branch lines were later abandoned, the symbiotic relationship between rails and towns became painfully evident. Communities lost their economic lifelines as transportation costs rose and market access diminished, accelerating rural decline and ultimately leading to town abandonment.

Peak-to-Abandonment Timeline

The dramatic rise and fall of Nebraska’s frontier towns followed a distinct timeline spanning approximately seven decades, from the post-Civil War homesteading boom through the devastating agricultural depression of the 1930s.

You can trace distinctive settlement patterns through three key periods: the 1860s-1890s expansion fueled by the Homestead Act, the 1870-1930 peak development era when communities flourished along strategic railroad placements, and the 1920s-1930s collapse.

These communities experienced profound economic shifts—thriving initially with grain elevators, stockyards, and bustling main streets, but ultimately succumbing to agricultural busts, drought, and transportation changes.

Towns typically spaced 6-10 miles apart (reflecting wagon transport limitations) prospered briefly before environmental challenges, market collapses, and highway transportation rendered many rail-dependent settlements obsolete by the late 1930s. The Union Pacific Railroad played a critical role in establishing these frontier settlements as it expanded westward, creating economic lifelines that determined which towns would thrive initially.

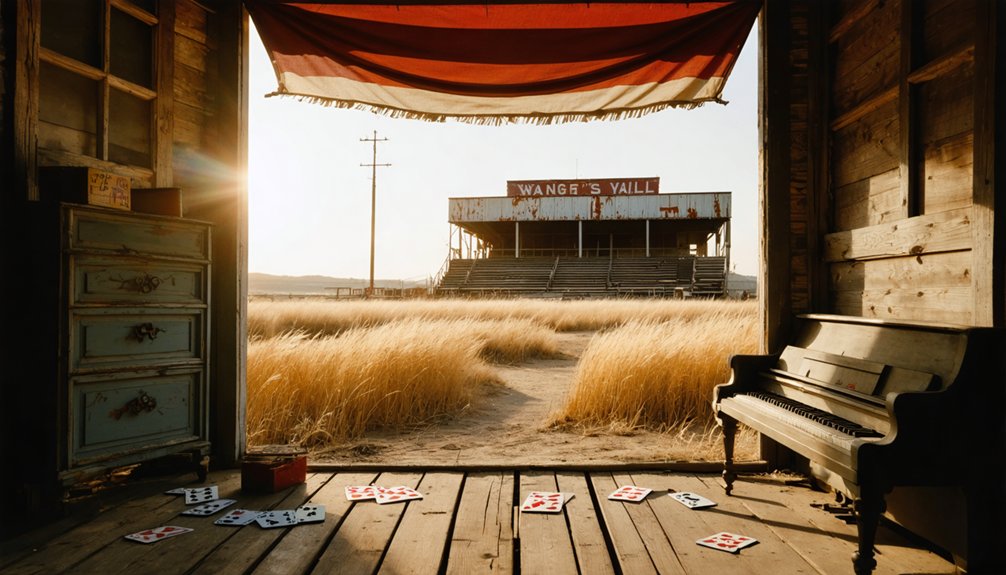

Venus: Dance Halls and Baseball Fields of a Lost Community

Venus once thrived as a vibrant social hub where community life revolved around key gathering places that fostered both entertainment and athleticism.

The town’s social infrastructure reflected the entrepreneurial spirit of frontier communities seeking connection despite geographic isolation. Through these venues, you’d have experienced the freedom of rural expression and community bonds. John and Anna Pospheshil established the park after relocating to the area in 1908. The area drew thousands of visitors during the Fourth of July celebrations in the 1920s.

- Oak View Park – featuring dance pavilions and a swimming pool, hosted Fourth of July celebrations and even performances by Lawrence Welk until its decline after 1948

- Venus Methodist Church – remains standing today as the most prominent landmark of the lost community

- Local dance hall – served as the epicenter for community gatherings and social engagement

- Baseball field – provided recreational opportunities that connected residents through America’s pastime

Morrillville: The Mill Town That Disappeared

The mill in Morrillville functioned as the economic heart of the community, providing jobs and attracting settlers to this frontier outpost in Scotts Bluff County.

You’ll find that as larger milling operations developed elsewhere, Morrillville’s commercial significance rapidly diminished, resulting in population decline and business closures.

While economic competition weakened the town’s stability, historical records indicate that recurring flood damage to the mill’s infrastructure ultimately rendered operations unsustainable, accelerating the community’s transformation into one of Nebraska’s forgotten places.

The town’s history shares parallels with modern climate change migration, as residents were forced to relocate when environmental factors made their homes uninhabitable.

Located at a similar elevation of 679 ft, Morrillville faced geographic challenges that contributed to its eventual abandonment, unlike its more resilient Indiana namesake.

The Mill’s Economic Impact

As the economic heartbeat of Morrillville, the grain mill established in the late 1880s fundamentally transformed the regional economy through multiple channels of influence.

The mill’s operations created a nexus of economic resilience that supported not just the town but surrounding agricultural communities.

The mill’s impact materialized in four distinct ways:

- Job creation for mill workers, farmers, and affiliated service providers

- Development of a regional supply chain for grain processing and distribution

- Attraction of complementary businesses that enhanced community identity

- Establishment of Morrillville as a commercial hub that connected isolated frontier farms

When the mill closed, this economic ecosystem collapsed, demonstrating how frontier towns often existed in fragile balance with their foundational industries—a pattern repeated across Nebraska’s abandoned settlements.

Floods Sealed Its Fate

Water proved to be Morrillville’s ultimate nemesis, destroying not just buildings but the town’s very future. You can trace the community’s demise through repeated flooding events that overwhelmed local infrastructure throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When floodwaters destroyed the mill—Morrillville’s economic heart—they severed the town’s lifeline. Despite attempts at flood mitigation, limited resources hampered these efforts.

Clay-rich soil prolonged flooding conditions while the valley’s topography funneled water directly into vulnerable structures. Community resilience faltered as residents faced stark choices after each inundation.

Roads washed out, water systems failed, and supply routes vanished. The once-thriving settlement emptied as citizens sought higher ground and stable employment elsewhere.

Archer: Victim of Government Land Resurveys

Founded in the summer of 1855 on public land along the east side of Muddy Creek in Richardson County, Nebraska, Archer represents a compelling case study of government policy‘s devastating impact on frontier settlements. This promising town was suddenly abandoned in 1857 when a government resurvey placed it outside the “Half-Breed Tract” boundary, stripping residents of their legal land claims.

The government resurvey impacts were profound:

- Legal land challenges arose as property rights were effectively nullified overnight.

- Commercial and legal activities ceased as residents fled.

- Neighboring settlements gained prominence as Archer dissolved.

- Land that once promised prosperity reverted to private ownership without the townsite legacy.

Archer’s brief existence exemplifies how shifting federal land policies could arbitrarily determine a frontier community’s fate.

Walnut: When the Post Office Closed, Hope Faded

Nestled among a prominent grove of walnut trees in Knox County, Walnut emerged as one of the region’s earliest settlements in 1872, establishing itself with two general stores and an essential post office that would ultimately determine its fate.

You’ll find that the post office significance extended far beyond mail delivery—it was Walnut’s lifeline. When it closed in 1924, the settlement’s decline accelerated rapidly. Cream and egg trucks stopped their routes, leaving only beer and pop deliveries continuing briefly.

Without this communication hub, the community’s social fabric unraveled.

Today, only crumbling foundations and cedar trees mark where a thriving frontier community once stood. The Walnut legacy lives primarily in historical records and fading local memories, its story mirroring countless other settlements that bloomed briefly on Nebraska’s frontier before withering into obscurity.

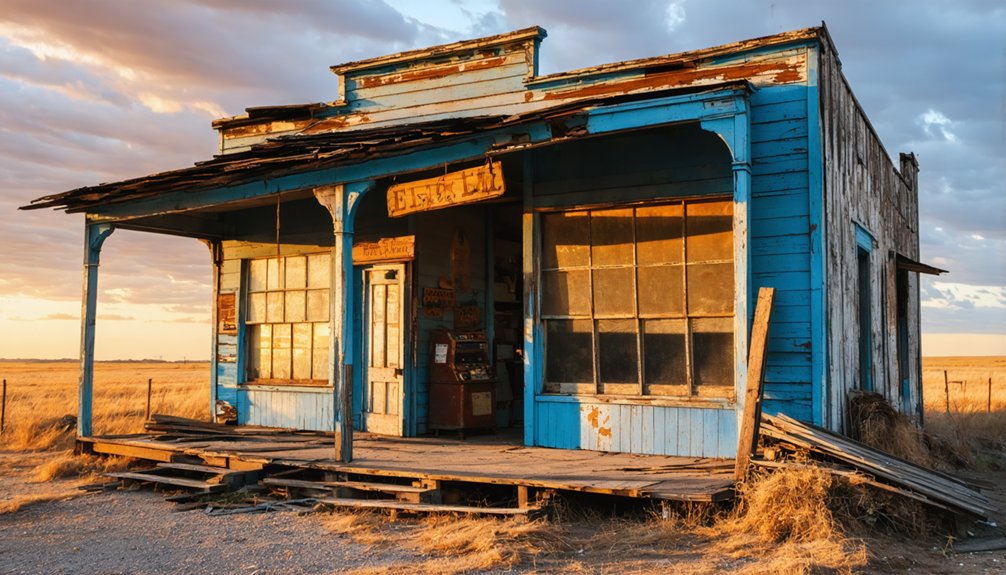

Sparta: Knox County’s Commercial Ghost

While Walnut’s fate hinged on its post office, neighboring Sparta built its identity around commerce—specifically, the Sparta Store, which emerged in 1887 as Knox County’s mercantile centerpiece.

This wood-clabbered structure with its full basement and adjacent living quarters served as a community hub for generations of rural Nebraskans.

The Sparta Store embodied frontier commerce in four distinct ways:

- Positioned strategically near a one-room schoolhouse before relocating in 1922

- Featured unusual amenities including repair facilities and residential space

- Provided essential goods to sustain isolated agricultural families

- Represented economic autonomy during Nebraska’s agricultural expansion

Unlike many similar structures, the Sparta Store remains remarkably intact—a weathered but unvandalized representation of Knox County’s commercial history and the self-reliance of its frontier inhabitants.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Ghost Town Buildings Be Legally Explored by Visitors?

You can’t legally enter ghost town buildings without the owner’s permission. Ghost town regulations require exploration permits or written authorization to avoid trespassing violations, regardless of the structure’s abandoned appearance.

How Many Nebraska Ghost Towns Have Been Completely Reclaimed by Nature?

Remarkably, dozens of Nebraska’s 60+ documented ghost towns have been completely reclaimed by nature. You’ll find places like Alkali and Oreapolis where nature reclamation has triumphed over ghost town preservation efforts.

Were Any Ghost Towns Later Resettled After Initial Abandonment?

Yes, you’ll find some Nebraska ghost towns were later resettled through absorption into larger towns, relocation after disasters, or renewed interest when transportation routes changed. Modern ghost towns occasionally experience limited resettlement efforts.

What Personal Artifacts Are Typically Found in Abandoned Nebraska Towns?

You’ll discover clothing, household goods, personal documents, toys, and jewelry—artifacts of historical significance that preservation efforts seek to protect for their analytical value in understanding frontier life’s freedoms and constraints.

Do Descendants of Original Settlers Organize Reunions at Ghost Towns?

Yes, you’ll occasionally find descendants organizing modest reunions at ghost town sites, though such reunion planning faces geographical challenges. Family histories motivate these gatherings, often facilitated by local historical societies rather than formalized annual events.

References

- https://history.nebraska.gov/finding-nebraskas-ghost-towns/

- http://govdocs.nebraska.gov/epubs/H6000/B020-2017.pdf

- https://history.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/doc_publications_NH1937GhostTowns.pdf

- https://history.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/5-year-09142022-WEBSITE.pdf

- https://negenweb.us/knox/stories/ghosttowns.htm

- https://history.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/doc_hp_SHPO_Nebraska-Preservation-Plan-2017-2021-revised.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iw21dwaXkck

- https://history.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/doc_publications_NH1989Historic_Places.pdf

- https://visitnebraska.com/trip-idea/explore-7-authentic-ghost-towns-nebraska

- https://history.nebraska.gov/blog/