Idaho’s abandoned gold mining towns include Custer, Bonanza, Silver City, Placerville, Rocky Bar, Atlanta, Bayhorse, Gilmore, Leesburg, and Sawtooth City. Each settlement emerged during the 1860s-1880s gold rush, flourished briefly, then declined as deposits diminished. You’ll find remarkably preserved structures in Silver City and Custer, while others like Boulder City have minimal remains. These ghost towns offer windows into the boom-and-bust cycle that defined Idaho’s mining heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Custer and Bonanza were twin mining settlements in Yankee Fork that flourished in the 1880s before being abandoned after 1904.

- Silver City contains over 75 original structures from the 1860s mining boom and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Rocky Bar once rivaled Boise with 2,500 residents but declined after an 1892 fire and now has only four permanent residents.

- Atlanta produced over $16 million in precious metals before mining operations ceased in 1957 due to isolation challenges.

- Other notable abandoned gold mining towns include Placerville, Gilmore, Leesburg, Sawtooth City, and Bayhorse.

The Rich Mining Heritage of Idaho’s Ghost Towns

When Idaho’s mountainous terrain revealed its golden treasures in the 1860s, it sparked a transformative period that would leave an indelible mark on the state’s landscape and history. These mountains harbored astonishing wealth, with operations like Quartzburg generating over $8 million by 1938.

You’ll find this mining legacy scattered throughout the Sawtooth Mountains, Salmon River range, and beyond. The Boise Basin became particularly significant after George Grimes discovered gold there in 1862, quickly transforming wilderness into thriving communities.

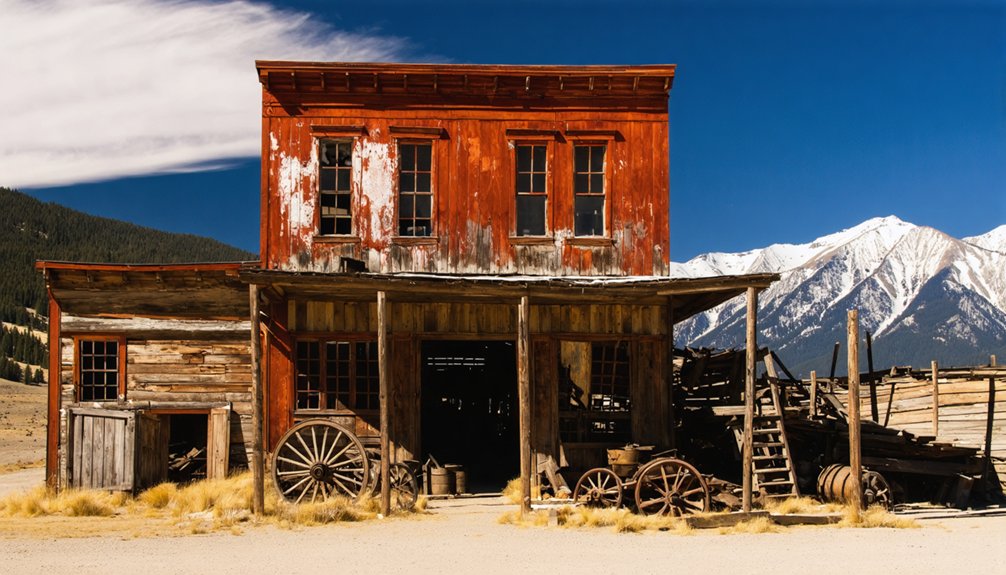

These weren’t mere work camps but vibrant communities complete with bunkhouses, schools, and diverse commercial establishments. Many of these sites now exist as neglected sites with only roofless ruins and rubble marking their former glory. During peak periods, mining towns supported populations reaching into the thousands, creating economic booms that attracted merchants and settlers alike.

Today, these abandoned settlements represent more than lost treasures—they’re physical representations of the ambitious spirit that shaped Idaho’s development, where fortune-seekers braved isolation and harsh conditions in pursuit of freedom and prosperity.

Custer and Bonanza: Twin Relics of Idaho’s Gold Rush

You’ll find the twin mining settlements of Custer and Bonanza inextricably linked in their parallel trajectories from bustling gold rush hubs to abandoned ghost towns within the Yankee Fork area.

While Custer rose to prominence after Bonanza’s devastating fires, reaching a peak population of 600 with extensive infrastructure including a 20-stamp mill and aerial tram systems, both towns ultimately succumbed to the boom-and-bust cycle typical of resource-dependent communities.

Their preserved remnants now serve as archaeological windows into Idaho’s mining past, where the General Custer Mill and Lucky Boy Mine operations once employed hundreds before economic forces rendered these vibrant communities nearly vacant by 1911. Visitors can walk through the high-ceilinged schoolhouse which once served as both an educational facility and social center for the mining community. Today, visitors can explore these historical sites at an elevation of 6,470 feet as part of the Land of the Yankee Fork State Park.

Prosperous Rise, Precipitous Fall

Following the momentous discovery of gold in Idaho’s Yankee Fork area in 1867, the twin settlements of Custer and Bonanza emerged as quintessential boom-and-bust mining communities that epitomized the volatile nature of frontier resource extraction.

You’ll find Custer’s prosperity peaked around 1880 when the General Custer Mill’s completion sparked tremendous growth, with its population reaching 350 by 1900. The sophisticated mill operation featured steam-powered crushing technology and an aerial tram, producing $8 million in gold before 1900.

However, these economic cycles proved brutally efficient—by 1894, the population had crashed to just 34 voters as high-grade deposits proved shallow.

These abandoned settlements experienced a brief revival when Lucky Boy Gold Mining Company purchased and overhauled operations in 1895, yet production inevitably declined after 1910, with the district yielding approximately 329,586 ounces of gold through 1959. The area’s geology consists primarily of contorted Paleozoic rocks that provided the rich veins yielding substantial gold deposits.

Sisters in Mining History

Two settlements, Bonanza and Custer, stand as interconnected relics of Idaho’s tumultuous gold rush era, sharing both proximity and parallel destinies along the Yankee Fork of the Salmon River.

These sisters’ stories began in 1877 when Charles Franklin established Bonanza, with Custer following in 1879 after significant gold discoveries nearby.

You’ll find their mining legacies interwoven—as Bonanza declined following devastating fires in 1889 and 1897, Custer absorbed its population and commerce.

Both towns flourished with populations reaching 600 during peak operations under various mining companies, including British-owned Dickens-Custer and later Lucky Boy.

Their shared fate was sealed when the Lucky Boy Mine and General Custer Mill closed in 1904, leaving both largely abandoned by 1910.

The area later saw renewed activity when the massive Yankee Fork Gold Dredge began operations in 1939, extracting approximately $11 million in ore before operations ceased in 1952.

Today, these preserved ghost towns offer evidence of Idaho’s rich mining heritage.

Bonanza initially thrived with multiple businesses including a saloon and the county’s first newspaper, with lots selling for $40 to $300 as the settlement rapidly expanded.

Preservation Versus Abandonment

The divergent fates of Custer and Bonanza illustrate a fascinating dichotomy in historical preservation that has shaped how we experience Idaho’s mining heritage today.

Custer’s robust preservation began with its 1981 National Register listing, sustained by the Friends of Custer Museum and Challis National Forest’s 1966 acquisition. These efforts preserved original structures like the saloon and jail, creating a window into mining camp life. Visitors can see the carefully restored schoolhouse where original wallpaper remains visible, offering authentic glimpses into 19th-century frontier education.

Bonanza faced insurmountable preservation challenges following devastating fires in 1889 and 1897. These disasters accelerated abandonment impacts as businesses relocated to Custer.

Bayhorse: From Gold to Silver in Lemhi County

Although initially discovered for its modest gold veins in 1864, Bayhorse‘s true significance in Idaho’s mining history emerged with the discovery of rich silver deposits in 1872 by W.A. Norton and associates.

This discovery transformed Bayhorse into a thriving mining community that would eventually produce over $10 million in minerals by 1898.

The Bayhorse history exemplifies the boom-and-bust cycle common to western silver mining settlements:

- Peak operations employed 200 men producing 80 tons of bullion monthly

- The 1880 establishment of a local smelter dramatically increased production efficiency

- By 1888, declining silver prices began the town’s inevitable downfall

- Despite hardships, mining continued until 1925, making it one of Idaho’s longest-running operations

You’ll find Bayhorse preserved today as part of Idaho’s Land of Yankee Fork State Park since 2009. The town reached its height with a population of approximately 300 residents during the 1880s and 1890s when silver mining was at its most profitable. The site was recognized for its historical significance when it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Silver City: The Patriarch of Idaho’s Mining Legacy

If you visit Silver City today, you’ll find remarkable historic preservation efforts that have maintained the Idaho Hotel, Owyhee County courthouse, and over 75 original structures despite the harsh mountain conditions.

The town’s preservation success stems from its National Register of Historic Places designation and the dedication of a small community that values its architectural heritage dating to the 1860s mining boom.

Silver City’s economic prominence depended on established trade routes that connected its million-dollar annual silver production to markets in San Francisco and beyond through a complex network of freight wagons, stagecoaches, and eventually telegraph lines that arrived in 1874.

Historic Preservation Efforts

Silver City stands as the crown jewel of Idaho’s historic mining preservation efforts, with approximately 70 original structures dating from the 1860s through the early 1900s remaining largely intact and minimally modernized.

These historic landmarks face significant preservation challenges as they balance authenticity with necessary maintenance. The Bureau of Land Management oversees much of the Silver City Historic District, supporting protection of this extensive mining community.

When you visit Silver City, you’ll experience:

- Walking original streets lined with commercial buildings, residences, and public structures

- Exploring the Idaho Hotel, which operates as both functional lodging and living museum

- Examining visible mine tunnels and ore-processing remnants that reveal early mining technology

- Connecting with mining history through carefully preserved cemeteries and authentic artifacts

Silver Trade Routes

The strategic position of Silver City as a nexus of commerce transformed it into the undisputed economic heart of the Owyhee mining district. You’d find an impressive network of stagecoach lines operating from this hub—among the largest in the Western U.S.—facilitating both silver transportation and connection to distant markets.

The mining logistics improved dramatically in the late 19th century with the extension of railroads near the town, enhancing ore movement efficiency and economic viability.

Silver City was also technologically advanced, becoming one of Idaho’s first towns with telegraph service in 1874 and telephone lines by 1880. These communication developments accelerated trade negotiations and resolved mining disputes more efficiently despite the town’s remote location.

This infrastructure supported the impressive output of over 250 mines that operated in the area between 1863 and the 1930s.

Placerville: Gold Rush Hub of Boise County

Discovered in late 1862, Placerville rapidly emerged as one of the earliest and most significant mining settlements in Idaho’s Boise Basin following the detection of exceptionally rich placer deposits.

Placerville history reveals a boomtown that reached several thousand residents by 1864, featuring 90 houses, 13 saloons, and extensive commercial infrastructure.

Mining techniques evolved from simple hand dredging to more sophisticated operations as miners contended with the region’s challenging water conditions:

- Initial placer mining operations utilized riffles to extract gold from creek beds

- Day-and-night intensive work compensated for short annual mining seasons

- Chinese miners later reworked lower-grade deposits abandoned by earlier prospectors

- Dredging operations continued into the 1940s, temporarily revitalizing the local economy

Though eventually overshadowed by Idaho City’s longer water season and larger operations, Placerville’s legacy endures as a quintessential gold rush community.

Gilmore: Rise and Fall of an Early 20th Century Mining Community

While Placerville represented the early gold rush era of the 1860s, Gilmore emerged decades later as Idaho’s quintessential early twentieth-century mining settlement. Originally named Horseshoe Gulch, the town was renamed after Jack T Gilmer, though with an altered spelling.

Gilmore’s history reveals a town that flourished with the arrival of the Gilmore & Pittsburgh Railroad in 1910, which revolutionized ore transportation. Mining techniques evolved from primitive methods using mule teams to more sophisticated operations at mines like Hilltop, Mountain Boy, and Portland, which extracted silver, lead, gold, and other metals valued at millions.

The town peaked at approximately 1,000 residents in the 1920s before declining after a 1927 power plant explosion. The final mine closed in 1929, and by 1957, Gilmore officially became a ghost town, leaving only scattered ruins for today’s visitors.

Rocky Bar: The True Ghost Town Experience

In contrast to many romanticized ghost towns that retain little authentic historical fabric, Rocky Bar presents perhaps Idaho’s most genuine window into the boom-and-bust cycle that characterized Western mining settlements.

Discovered in 1863 during the South Boise mining rush, this remote settlement exemplifies Rocky Bar’s resilience through multiple phases of development.

Unearthed during the South Boise gold fever, Rocky Bar endured through cycles of boom and bust with remarkable persistence.

Your ghost towns exploration will reveal:

- A former county seat with nearly 2,500 residents that once rivaled Boise in size

- The devastating 1892 fire that marked the beginning of its decline

- Extensive milling operations that outpaced all other Idaho districts by 1866

- The preserved Masonic Hall, rebuilt after the fire by George Golden

Today, with just four permanent residents, Rocky Bar stands as a symbol of the transitory nature of mining prosperity.

Atlanta and Burke: Tales of Natural Disaster and Abandonment

You’ll find contrasting tales of survival in Atlanta and Burke, where prosperity collapsed under different pressures despite promising beginnings.

Atlanta’s gold and silver production faced decades of struggle against geographic isolation and ore processing challenges before finally achieving significant output after 1932.

Burke, meanwhile, experienced devastating fires in 1890 and 1910 that accelerated its eventual decline into a semi-ghost town, leaving behind only remnants of its once-thriving mining operations.

Surviving Natural Catastrophes

Natural catastrophes served as defining elements in the histories of Atlanta and Burke, two remote Idaho mining settlements whose fates were inextricably linked to their harsh environments.

You’ll find their natural resilience tested against formidable geographical and environmental obstacles that ultimately shaped their destinies.

Atlanta’s 5,300-foot elevation in the isolated Sawtooth Mountains and Burke’s precarious canyon location created conditions where environmental adaptation became essential for survival:

- Severe winters regularly isolated communities, limiting mining operations and vital supplies

- Refractory silver ore challenged processing capabilities, hampering economic sustainability

- Difficult terrain required specialized transportation infrastructure, delaying development

- Recurring floods, fires, and ground instability threatened permanent settlements

Despite technological advances like Atlanta’s Middle Fork road in 1938, these towns couldn’t overcome the cumulative effects of their environmental struggles, transforming them into the semi-ghost towns you’ll encounter today.

Prosperity to Desolation

While prospectors initially flocked to Atlanta and Burke with dreams of striking it rich, these remote Idaho mining towns ultimately followed the boom-and-bust pattern characteristic of western frontier settlements.

Atlanta’s isolation in the Sawtooth Mountains created immense challenges. After discovering gold in 1863 and the Atlanta lode in 1864, the town struggled with refractory silver ore that early technology couldn’t process economically.

Despite producing over $16 million in precious metals, mining operations ceased after 1957, transforming Atlanta into a prime destination for ghost town exploration.

The environmental legacy remains troubling, with arsenic contamination in Montezuma Creek highlighting the ecological costs of abandoned mining operations.

Today, you’ll find standing structures including the historic jail, offering opportunities for mining heritage preservation while serving as stark reminders of prosperity’s fleeting nature in these frontier boomtowns.

Leesburg and Sawtooth City: Hidden Gems of Idaho’s Mining Past

Nestled within Idaho’s rugged wilderness lie two remarkable relics of the state’s gold rush era: Leesburg and Sawtooth City.

These hidden treasures emerged following gold discoveries—Leesburg in 1866 and Sawtooth City in 1879—each experiencing meteoric growth before inevitable decline.

Leesburg’s mining legacies include over $6 million in gold production across decades of operation, while Sawtooth City flourished briefly with over 1,000 residents before fading by the late 1880s.

- Leesburg, named for Confederate General Robert E. Lee, grew from nothing to 2,000 residents within months.

- Unlike typical mining settlements, Leesburg maintained relative peace and cooperation.

- Chinese miners remained after most departed, continuing extraction operations.

Both towns now stand as protected historical sites, with Leesburg on the National Register since 1975.

Exploring Idaho’s Mining Towns Today: What Visitors Can Expect

How does one step back into the nineteenth century while standing firmly in the present? Idaho’s ghost towns offer this temporal portal through their preserved structures and mining relics.

In Custer, you’ll find guided historic tours of meticulously restored buildings, complemented by the nearby Yankee Fork Gold Dredge—among America’s best-preserved gold mining machines.

Silver City maintains its authentic character with privately owned historical structures, including a summer-operating hotel for intrepid explorers.

Bayhorse showcases exceptional stone buildings and charcoal kilns within its trails system, while Mackay’s Mine Hill presents a thorough complex of abandoned infrastructure.

Unfortunately, Boulder City offers minimal remains due to vandalism.

Each location presents varying levels of preservation, allowing you to experience Idaho’s mining heritage from well-maintained museums to ruins whispering tales of frontier ambition.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Is the Best Time of Year to Visit Idaho’s Ghost Towns?

The golden rays of summer (June-August) offer ideal conditions for your ghost town explorations, while early fall rewards you with spectacular fall foliage but fewer crowds. You’ll enjoy summer hiking with longer daylight hours.

Are There Guided Tours Available for These Abandoned Mining Towns?

You’ll find guided history tours at Custer, Bayhorse, and Silver City, while local tour operators occasionally arrange excursions to other sites, balancing structured exploration with your freedom to discover Idaho’s mining heritage.

How Accessible Are These Ghost Towns for Visitors With Mobility Limitations?

Most ghost towns offer limited accessibility with few accessible routes for visitors with mobility limitations. Silver City provides better options, but you’ll generally need specialized mobility aids for these remote, rugged sites.

What Artifacts Can Legally Be Collected From These Historical Sites?

You can’t legally collect most artifacts from Idaho’s ghost towns. Legal regulations prohibit removing historical items, as artifact preservation laws protect these cultural resources on public and private lands.

Are There Paranormal Investigations or Ghost Hunting Tours Offered?

Despite what your smartphone might suggest, you won’t find many official paranormal activities in Idaho’s mining ghost towns. Ghost hunting opportunities remain limited, with most sites lacking organized supernatural tours.

References

- https://motoidaho.com/articles/gold-mining-ghost-towns-near-boise/

- https://www.thegoldminehotel.com/ghost-towns-and-haunted-places-in-idaho

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Idaho

- https://idaho-forged.com/idahos-ghost-towns-eerie-yet-approachable/

- https://history.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/0064.pdf

- https://westernmininghistory.com/state/idaho/

- http://www.fs.usda.gov/r01/idahopanhandle/recreation/idaho-gold-and-ruby-mine-boulder-city-ghost-town

- https://visitidaho.org/things-to-do/ghost-towns-mining-history/custer-historic-mining-town/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/idaho/custer/

- https://www.islands.com/1748075/custer-ghost-town-wild-west-ghostly-charm-abandoned-idaho-timeless-beauty/