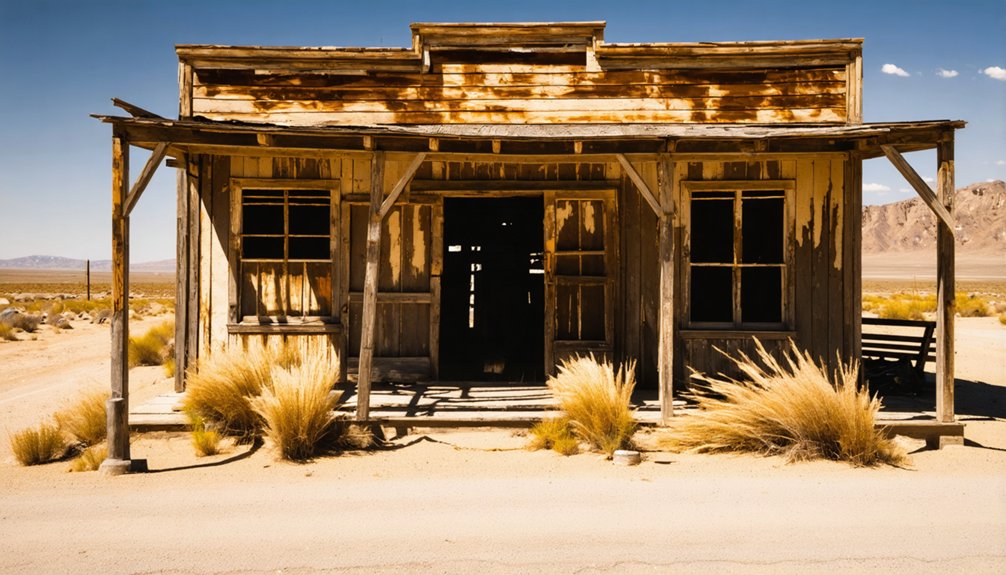

Rincon was a thriving agricultural community along California’s Santa Ana River until the catastrophic 1938 flood devastated the settlement. After this disaster, the federal government built Prado Dam in 1941, permanently converting the area into a flood control basin. Unlike typical ghost towns abandoned for economic reasons, Rincon’s erasure resulted from deliberate infrastructure policy prioritizing regional water management over local community preservation. The submerged town reveals complex trade-offs in California’s water history.

Key Takeaways

- Rincon was a thriving agricultural settlement along the Santa Ana River that became a ghost town after the 1938 flood.

- The community was permanently abandoned when Prado Dam’s construction in 1941 converted the area into a flood control basin.

- Originally part of Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes land grant, Rincon developed as a farming community with irrigation systems.

- Unlike typical ghost towns abandoned due to resource depletion, Rincon was sacrificed for regional water management priorities.

- The settlement site now lies underwater during wet seasons as part of Prado Dam’s reservoir.

The Spanish Corner: Origins of Rincon’s Settlement

When Spanish colonization expanded into California following the 1521 conquest of the Aztec Empire, it laid the groundwork for settlements like Rincon. The area was initially part of Spanish Land Grants, specifically Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes, granted to Bernardo Higuera and Cornelio Lopez in 1821.

Spanish expansion into California brought European settlement to lands that would become Rincon through the rancho system of territorial control.

These ranchos established the economic foundation for early Californio society, centering on cattle grazing and agriculture. The Higuera family, with connections to local Pueblo leadership, helped solidify Spanish governance in the region. The name Rincón de los Bueyes, meaning Corner of the Oxen, referred to a natural corral formation in the landscape.

Indigenous Relations were fundamentally altered as the Spanish encountered Luiseño (Payomkawichum) communities. Native peoples who’d thrived along the San Luis Rey River faced forced resettlement and labor through the mission system. Similar to the Boronda Adobe, many historical adobe structures were constructed during this period on ranchos throughout California.

Despite colonial pressures, these groups maintained cultural ties to their ancestral water sources, an essential element of their pre-contact subsistence practices.

Life Along the Santa Ana River: 1870-1907

Three pivotal factors defined life along the Santa Ana River between 1870 and 1907: agricultural innovation, community development, and environmental adaptation.

You’d find settlers transforming the fertile riverbanks through extensive river irrigation systems pioneered by Chapman, Peralta, and Yorba families. Their ditches enabled agricultural diversity unattainable elsewhere in the region.

- Cultivation Revolution – Farms produced wheat, barley, oranges, grapes for wine, and walnuts, creating economic independence.

- Settlement Patterns – Communities like Santa Ana Arriba strategically positioned on high ground, balancing flood risk with water access.

- Infrastructure Growth – Schools, churches, and transportation networks emerged by the 1870s, linking isolated agricultural communities.

The river’s unpredictable nature shaped these developments, with flooding and course changes constantly challenging settlers’ determination to tame this essential waterway. The drought of 1863-64 devastated local rancheros, forcing many to sell their lands and fundamentally changing settlement patterns in the region. The Rancho Santiago de Santa Ana stretched an impressive 25 miles from the ocean to the mountains, encompassing land that would later include these riverside communities.

When the Waters Rose: The 1938 Flood and Abandonment

The catastrophic flood of 1938 marked a defining moment in Rincon’s history, fundamentally altering both its physical landscape and community destiny. From February 27, the Santa Ana River, swollen by five days of torrential rainfall and snowmelt, overwhelmed the settlement with devastating force. Pacific storms generated nearly one year’s worth of precipitation in just a few days, creating impossible conditions for the small community.

The flood impact was cataclysmic—waters rose nearly 30 feet above normal when debris clogged the nearby railway bridge, crushing homes and sweeping away farms. The destruction mirrored scenes from Anaheim where an eight-foot wall of water surged after levee failures.

Waters surged 30 feet high when debris jammed the railway bridge, destroying everything in their merciless path.

Community resilience emerged through survival stories like the Moreno family, who sought refuge in barns as their world washed away. Yet this 50-year flood proved insurmountable for Rincon’s future.

With flows reaching 317,000 cubic feet per second—approaching half the Mississippi River’s volume—the waters transformed the area into a temporary lake, ultimately leading to the community’s abandonment and ghost town status.

From Village to Dam: How Prado Changed the Landscape

Following the devastating 1938 flood that sealed Rincon’s fate, federal authorities initiated a transformative engineering solution that would permanently alter the region’s landscape and community makeup.

The 1941 completion of Prado Dam by the Army Corps of Engineers converted approximately 7,000 acres of farmland and residential property into a flood control basin through eminent domain and property purchases.

The dam construction dramatically reshaped both the physical landscape and human geography:

- Former residents were displaced to nearby communities like Corona and Norco

- The seasonal reservoir now covers the ghost town, with the basin remaining dry except during peak runoff periods

- Sediment accumulation has continuously reduced the reservoir’s capacity, necessitating ongoing maintenance

This massive flood control project ended recurrent winter flooding, enabling suburban development downstream while permanently erasing Rincon’s physical presence from the map. Recent plans to raise the dam by 28 feet higher could further bury any remaining archaeological evidence of the once-thriving community. The earthen dam structure, measuring 2,280 feet in length, serves as a lasting physical reminder of the region’s transformation.

Forgotten Legacies: Rincon’s Place in California’s Ghost Town History

While numerous California ghost towns emerged from abandoned mining operations, Rincon stands apart as a community erased not by economic decline but by deliberate infrastructure policy.

When you examine its historical significance, you’ll find a settlement sacrificed for water management priorities—the Prado Dam construction physically removing what floods hadn’t already destroyed.

Unlike typical ghost towns that slowly declined as resources depleted, Rincon’s transformation was abrupt and state-mandated.

Its inclusion in California’s Ghost Town registry documents a different pattern of community dissolution, where government infrastructure projects superseded established settlements.

This legacy exemplifies how mid-20th century development often prioritized regional water security over preserving local communities, reflecting broader patterns where rural agricultural settlements yielded to industrialization across the American West. Unlike Rincon Hill, which was transformed by the Second Street Cut in 1869, impacting its affluent residential character. The area was originally a Chumash village named Shuku before European settlers arrived and transformed the landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Were Rincon’s Most Notable Residents or Families?

You’ll find Rincon’s notable families included the Churches, Seders, and Fullers. Historical figures like Thomas Selby, William Ralston, and literary icons Bret Harte and Jack London defined this fashionable elite neighborhood.

Can Visitors Access Any Remaining Rincon Ruins Today?

No, you can’t access Rincon Island ruins today. The artificial island remains closed to visitors during ongoing decommissioning activities under California State Lands Commission control until at least 2026-2027.

What Crops or Industries Sustained Rincon’s Economy?

Gold mining initially fueled Rincon like a fever, but agricultural practices couldn’t sustain momentum. You’d find limited subsistence farming, cattle ranching, and service businesses preceded inevitable economic decline after gold reserves disappeared.

Were There Indigenous Settlements at Rincon Before Spanish Colonization?

Yes, you’ll find that Wáșxa, a Luiseño indigenous settlement, existed at Rincon before Spanish colonization. Indigenous settlement patterns confirm Payómkawichum people inhabited this area for over 10,000 years before European contact.

Did Rincon Have Schools, Churches, or Other Community Institutions?

In Rincon’s million-year history, you’d find its historical significance included modest community institutions. Churches, schools, and civic buildings served as anchors for this settlement before its eventual decline into obscurity.

References

- https://www.thetowersatrincon.com/blog/a-history-of-rincon-hill

- https://capitolmuseum.ca.gov/state-symbols/silver-rush-ghost-town-calico/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rincon_Island_(California)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rancho_El_Rincon

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ElbXVNDurPc

- https://www.cheviothillshistory.org/home/miscellany/spanish-mexican-ranchos/

- https://mchsmuseum.com/local-history/historic-places/rancho-rincon-del-sanjon/

- https://www.visitcalifornia.com/experience/rincon-band-luiseno-indians-museum/

- https://www.foundsf.org/EARLY_SETTLEMENT