You’ll find the ghost town of Castolon within Big Bend National Park, where a vibrant border community once thrived in the early 1900s. Founded by Cipriano Hernández in 1903, the settlement grew to 300 residents, supported by agriculture and a military presence during the Mexican Revolution. La Harmonia Company’s trading post served as the town’s commercial hub until economic pressures and the army’s 1921 withdrawal led to its decline. Today’s preserved historic district reveals Castolon’s rich cultural heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Castolon was established in 1903 by Cipriano Hernández near Santa Elena Canyon, growing to 300 residents before becoming a ghost town.

- The community declined drastically from several hundred to 25 residents following military withdrawal and economic hardships in the 1920s.

- Now preserved within Big Bend National Park, Castolon’s historic buildings showcase its past as a military outpost and trading center.

- Agricultural challenges, including drought and market pressures, contributed to the settlement’s abandonment despite initial farming success.

- Original structures from Camp Santa Helena and La Harmonia Company’s trading post remain as tourist attractions in the ghost town.

The Birth of a Rio Grande Settlement

When Cipriano Hernández purchased land near Santa Elena Canyon in 1903, he laid the foundation for what would become the settlement of Castolon. Naming the area Santa Helena, he harnessed the Rio Grande’s water through irrigation techniques that transformed the harsh landscape into productive farmland. His settler motivations focused on agricultural opportunity, growing wheat, corn, and oats for commercial sale. The La Harmonia Company would later establish a major trading post in 1918, becoming central to the area’s commerce.

You’ll find that Hernández’s success drew others to this frontier outpost. Patricio Márquez established a second store, while pioneers like Agapito Carrasco and Ruperto Chavarria led groups forming nearby communities. The settlers later requested U.S. Army protection in 1910 as the Mexican Revolution intensified along the border.

Despite the challenging environment of sparse vegetation and intense sun, these determined settlers persevered. By the early 1900s, you’d have encountered a thriving community of 200-300 residents, marking the birth of this distinctive Texas border settlement.

Military Presence During the Mexican Revolution

You’ll find that the U.S. Army’s arrival in Castolon began in 1911 when cavalry troops established camps along the Rio Grande to counter revolutionary forces and bandits crossing from Mexico.

The military’s presence expanded with the establishment of Camp Santa Helena in 1916, staffed by rotating detachments from the 5th, 6th, and 8th Cavalry units.

Your understanding of this period wouldn’t be complete without noting that Camp Marfa provided infantry support to the cavalry operations, creating a coordinated defense network along the Texas-Mexico border during the Revolution’s most volatile years.

Visitors can explore this rich military history in the Castolon Historic District, where remnants of the settlement and military presence are preserved within Big Bend National Park.

Cavalry Troop Arrives 1911

In response to growing tensions along the Texas-Mexico border during the Mexican Revolution, a U.S. cavalry troop established its presence in Castolon by 1911.

The 5th, 6th, and 8th Cavalry regiments rotated through this strategic outpost, implementing cavalry tactics suited to the harsh desert terrain. You’ll find that their troop logistics involved living in tents while conducting mounted patrols to protect American settlements from revolutionary violence and bandit raids. The soldiers patrolled a 300-mile stretch of the Rio Grande to maintain border security.

These cavalry units transformed Castolon into an essential military stronghold, providing rapid response capabilities across the remote frontier.

Their presence attracted support services and boosted the local economy, while their protective role encouraged stability in the region. The military’s efforts to establish Camp Santa Helena in 1919 further demonstrated their commitment to the area.

Despite challenging environmental conditions, the cavalry’s arrival marked a significant chapter in Castolon’s evolution as a strategic border site.

Border Conflicts Drive Protection

As violence from the Mexican Revolution spilled across the Rio Grande in 1910, the U.S. Army responded by establishing military outposts to protect frontier communities.

You’d have found cavalry units from the 5th, 6th, and 8th regiments patrolling the border, operating from bases like Camp Santa Helena near Castolon.

Border security became paramount as raiders and revolutionaries exploited the chaos, threatening both American and Mexican settlers. The Army’s presence helped shield local ranches, farms, and trading routes from attack.

While soldiers initially lived in tents, they began constructing permanent facilities by 1919. Their protection fostered civilian resilience, allowing communities on both sides of the river to maintain their livelihoods despite the upheaval.

Camp Marfa Infantry Support

The establishment of Camp Marfa in 1911 marked a significant expansion of U.S. military presence along the Texas-Mexico border.

You’ll find that military logistics centered around supporting 400 troops who maintained a network of 14 border posts, with daily provisions including 2,500 pounds each of beans and flour, alongside substantial quantities of sugar and coffee.

The camp’s troop deployment focused on deterring cross-border violence during Mexico’s revolutionary period. Originally designated as Camp Albert, the installation played a vital role in border security operations. The fort became headquarters for coordinating large military operations with National Guard units from multiple states.

You’d have witnessed soldiers conducting essential escort missions, including a notable four-day operation moving Mexican refugees and federal troops from Presidio.

The Army Signal Corps operated reconnaissance flights from the base while cavalry units patrolled the Rio Grande, preventing arms smuggling to revolutionaries like Pancho Villa’s forces.

Agricultural Life and Economic Growth

While harsh desert conditions challenged early settlers, Castolon’s agricultural foundation began in 1903 when Cipriano Hernández purchased Rio Grande bottomland and established irrigation systems for grain cultivation. His success inspired other farmers to migrate to the area, establishing a thriving agricultural community focused on crop diversity and self-sufficiency.

You’ll find that farming remained central to Castolon’s identity even during the Mexican Revolution, when many families sought refuge in the area between 1912-1920.

The establishment of Camp Santa Helena in 1916 provided stability for agricultural expansion. Farmers grew wheat, corn, oats, beans, and cotton, while innovative irrigation techniques helped overcome the region’s limited rainfall.

Community Hub Along the Border

Situated strategically along the Rio Grande, Castolon emerged from its agricultural roots to become a vibrant cross-border community hub by the early 1900s.

You’ll find evidence of remarkable cultural exchange in the establishment of La Harmonia Enterprises, which served both American and Mexican settlers who called this frontier home.

The community’s resilience shone through as Mexican families fleeing the revolution between 1912-1920 integrated seamlessly with existing American settlers.

Despite the U.S. Army’s presence at Camp Santa Helena during border tensions, Castolon maintained its role as a peaceful meeting point.

Even with military oversight during troubled times, Castolon remained a place where people came together in harmony.

The surrounding settlements of El Ojito and La Coyota reinforced Castolon’s position as a crucial center where diverse peoples traded goods, shared resources, and forged lasting connections across cultural boundaries.

The Path to Abandonment

You’ll find that Castolon’s decline began with devastating economic blows, as cotton prices plummeted in the late 1920s while soil depletion and harsh desert conditions made farming increasingly difficult.

Like the fate of historic Indianola, which now lies submerged beneath Matagorda Bay, Castolon’s strategic location could not save it from eventual abandonment.

The withdrawal of U.S. Army protection, which had previously safeguarded the community during the Mexican Revolution, left residents vulnerable to border instability and heightened immigration enforcement in the 1930s.

The establishment of Big Bend Park prompted further exodus from the region.

Agricultural dreams withered as these combined pressures forced many families to abandon their farms, contributing to the town’s population dropping from several hundred to just 25 residents.

Economic Hardships Strike Hard

Mounting economic pressures in the early 20th century dealt devastating blows to Castolon’s survival as a viable settlement. The community’s economic vulnerability stemmed from its dependence on subsistence farming and limited trade opportunities, while rural isolation prevented meaningful market access.

You’d have found the settlement struggling against devastating environmental challenges, with floods and droughts wreaking havoc on agricultural production.

Local farmers couldn’t generate enough surplus to establish sustainable commercial operations.

The community’s youth began seeking opportunities elsewhere, creating critical labor shortages.

When the Great Depression hit, it accelerated Castolon’s decline, as limited capital and reduced consumer spending power crippled local businesses.

The combined impact of these economic hardships, coupled with the region’s harsh environmental conditions, ultimately pushed the settlement toward abandonment.

Military Protection Withdraws

As economic hardships gripped Castolon, another devastating blow came with the withdrawal of military protection in 1921.

You’d have seen the U.S. Army pack up and leave Camp Santa Helena, taking with them the security that had shielded settlers from border violence since 1916.

The military withdrawal created an immediate security vacuum along the Rio Grande.

Wayne Cartledge and other residents watched with growing concern as the cavalry units that once patrolled their lands disappeared.

Without the 5th, 6th, and 8th Cavalries standing guard, you’d have felt exposed to potential raids and banditry.

Though the $22,000 worth of military infrastructure remained – including modern barracks, quarters, and utility systems – the absence of armed patrols left settlers vulnerable in this harsh borderland region.

Agricultural Dreams Fade Away

The agricultural foundation that once defined Castolon began crumbling in the early 1920s, despite the region’s initial promise for farming.

You’ll find that while early settlers like Cipriano Hernández established diverse crop operations, several critical factors led to the area’s decline:

- The harsh desert climate and poor soil conditions made consistent crop yields nearly impossible, even with Rio Grande irrigation.

- A shift from subsistence farming to cotton production left the community vulnerable to market fluctuations.

- The Mexican Revolution’s disruption of border communities weakened the agricultural infrastructure.

- Environmental challenges, including drought and extreme heat, proved too formidable for sustainable farming.

Though farmers attempted to diversify their crops and adapt to the challenging conditions, Castolon’s farming challenges ultimately proved insurmountable.

You can still see remnants of this agricultural past scattered among abandoned buildings and machinery.

Historical Legacy in Big Bend National Park

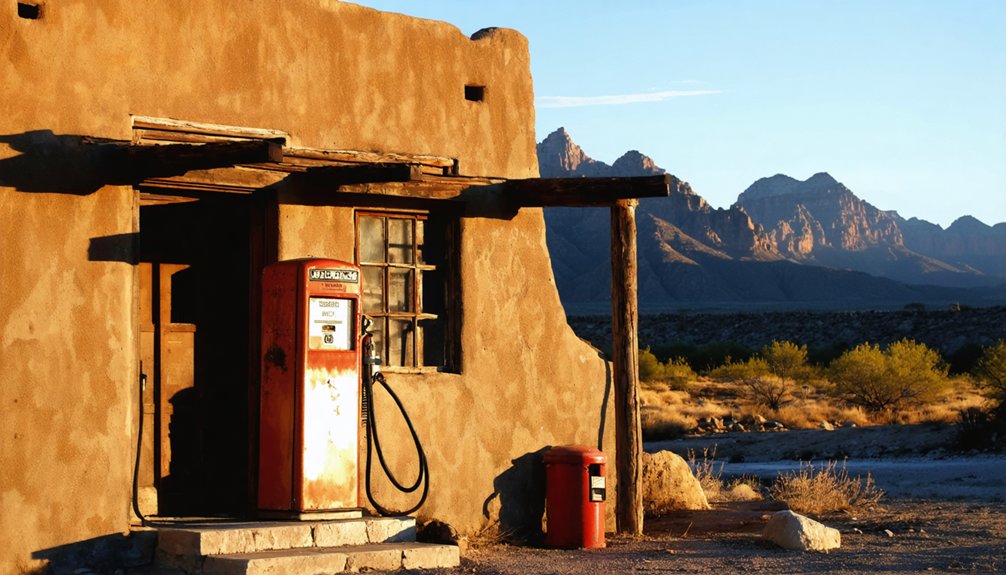

Located within Big Bend National Park, Castolon stands as one of the region’s most significant historical sites, representing a complex tapestry of U.S.-Mexican cultural integration from the early 1900s through 1961.

Through cultural blending, Hispanic traditions merged with Anglo-American influences, creating a unique bicultural community that flourished despite harsh conditions and the turbulent Mexican Revolution.

You’ll find evidence of this rich past in the preserved military structures of Camp Santa Helena, built by the 5th Cavalry in response to border raids.

The site’s historical preservation includes original buildings that once served as a crucial hub for commerce, postal services, and law enforcement.

Today, you can explore these remnants along Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive, where interpretive exhibits bring to life the story of this remarkable frontier community.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Artifacts Can Visitors Find in Castolon’s Abandoned Buildings Today?

Inside crumbling adobe walls, you’ll discover abandoned artifacts like rusty door hinges, weathered wooden frames, and historical treasures including ceramic fragments, glass bottles, and farming tools from early 1900s border life.

How Did Residents Get Medical Care in Early Castolon?

You’d find residents relied heavily on local remedies and mutual community aid, as medical supplies were scarce. Military personnel at Camp Santa Helena offered limited care until 1921, while serious cases required distant travel.

What Traditional Celebrations and Festivals Were Held in Castolon?

Ever wonder how settlers kept their spirits high? You’d find traditional dances blending Mexican and Anglo cultures, harvest festivals celebrating fall bounty, religious fiestas, and saint’s day celebrations throughout the year.

How Did Children Receive Education in Early Castolon?

You’d learn in one-room schoolhouses where teachers taught basic literacy, arithmetic, and practical skills. The early curriculum balanced English and Spanish instruction while adapting to farming seasons and local needs.

What Wildlife Commonly Interacted With Castolon’s Inhabitants During Its Active Years?

Quick as a coyote’s howl, you’d spot desert creatures like mule deer, turkey vultures, and rattlesnakes near your homestead, while wildlife interactions with jackrabbits, mountain lions, and bats shaped daily life.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castolon

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/castolon-tx

- http://www.texasescapes.com/TexasGhostTowns/CastolonTexas/CastolonTexas.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/tx/tx.html

- https://www.texasalmanac.com/places/castolon

- https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2015/12/unknown-cache-letters-mailed-ghost-town-may-rewrite-history-big-bend-national-park

- http://www.forgottenfrontiers.com/big-bend-revealed

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TOWNS/Texas_ghost_towns.htm

- https://www.simplytexan.com/truly-texan/abandoned-ghost-towns-in-texas/