Chivington, Colorado was once a bustling railroad boomtown with 1,500 residents that emerged in 1887 as a Missouri Pacific division point. You’ll find it named after Colonel John Milton Chivington, the controversial military leader responsible for the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre. Today, only deteriorating structures remain, including an Italianate schoolhouse and Friends Church, silent witnesses to economic collapse after the railroad’s departure. The nearby Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site offers deeper context to this complex settlement.

Key Takeaways

- Chivington was a once-thriving Colorado railroad boomtown that grew to 1,500 residents by 1888 before declining into abandonment.

- The town was named after Colonel John Milton Chivington, who became infamous for leading the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre.

- Railroad departure caused Chivington’s economic collapse, transforming it from a bustling hub to today’s ghost town.

- Remaining structures include a deteriorating two-story Italianate schoolhouse and a solitary Friends Church amid prairie ruins.

- Nearby Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site preserves the memory of the atrocity that overshadows the town’s namesake.

The Rise of a Railroad Boomtown

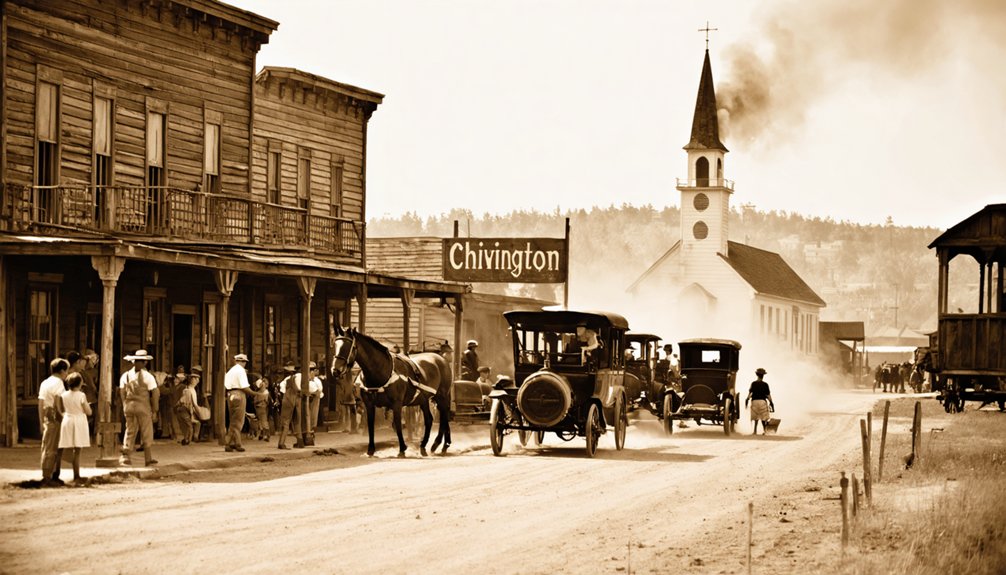

When the Missouri Pacific Railroad expanded into eastern Colorado’s plains in 1887, Chivington emerged as a strategically positioned boomtown, marking a significant chapter in the region’s railroad development.

Located 116 miles from Pueblo and 600 miles from Kansas City, this “C” in the alphabetical sequence of railroad towns quickly became a crucial division point.

Strategically positioned between major hubs, Chivington rose to prominence as a vital railroad connection point on Colorado’s eastern plains.

You’ll find Chivington’s economic opportunities exploded as its population surged to over 1,500 residents by 1888.

The construction of a division roundhouse in fall 1887 cemented its importance, attracting substantial capital investment.

The town rapidly established essential infrastructure—hotels, eating houses, and various commercial enterprises—serving both permanent residents and transient railroad workers.

This railroad expansion transformed what would become a mere spot on the plains into a bustling commercial center.

Chivington was named after Colonel John M. Chivington, following Jessie Mallory Thayer’s alphabetical naming convention for towns along the railroad route.

For visitors seeking information about Chivington, it’s important to note that various disambiguation pages exist to clarify the different meanings associated with this name.

The Legacy of Colonel John Milton Chivington

Colonel John Milton Chivington, the town’s namesake, began his career as a Methodist minister before transforming into a controversial military leader whose early Civil War heroism at Glorieta Pass would be overshadowed by his actions.

You’ll find his legacy permanently stained by his leadership of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, where his troops slaughtered hundreds of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho people, including women and children. Despite warnings from officers like Captain Silas Soule who refused to attack, Chivington proceeded with the brutal assault. Following the massacre, Chivington falsely portrayed the event as a military victory against hostile forces to justify his actions.

His dramatic fall from respected community leader to reviled historical figure exemplifies how a single atrocity can define a man’s place in history, despite his earlier contributions.

Controversial Military Leader

Although initially celebrated as a Civil War hero for his decisive victory at Glorieta Pass, John Milton Chivington’s military legacy remains permanently shadowed by his leadership during the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864.

Chivington’s leadership throughout his military career reflects stark contradictions. The former Methodist minister shifted to combat specifically to fight slavery, yet later commanded troops who slaughtered Native Americans under protection of the U.S. Army. After the Sand Creek Massacre, he proudly displayed scalps and body parts taken from the victims during public appearances. The village that Chivington attacked contained approximately 800-900 Native Americans, mostly women, children, and elderly.

Despite multiple government investigations revealing atrocities committed under his command—including the killing of non-combatants and mutilation of bodies—Chivington steadfastly defended the attack as “glorious” and militarily necessary. This military controversy defined his historical reputation, transforming him from celebrated colonel to polarizing figure.

While some Colorado settlers supported his actions, many military contemporaries condemned the massacre that occurred beneath both American and white surrender flags.

Massacre’s Lasting Impact

The Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, perpetrated under Chivington’s command, reverberates through American history as a pivotal moment of national shame and Indigenous trauma.

When you visit the massacre site today, you’ll find a national historic memorial preserving massacre memory through educational exhibits and commemorative markers.

The atrocity profoundly altered U.S.-Native relations, triggering retaliatory conflicts and undermining peace efforts by leaders like Chief Black Kettle.

For Cheyenne and Arapaho communities, the murder of 150-230 of their people—mostly women, children, and elders—represented not just immediate devastation but intergenerational trauma.

Despite initial celebration in Denver, three federal investigations condemned the massacre, marking a rare official denouncement.

Indigenous resilience remains evident in ongoing cultural revival initiatives and oral histories that honor victims while ensuring this dark chapter isn’t forgotten. The site is located approximately 9 miles north of the town of Chivington, Colorado, making it accessible for those seeking to understand this tragic event.

Both Black Kettle and White Antelope had been actively seeking peaceful negotiations with U.S. authorities before the unprovoked attack occurred.

From Minister to Infamy

Behind the town’s namesake lies a man whose journey from pulpit to infamy epitomizes the complex moral contradictions of America’s western expansion.

Chivington’s ministerial transformation began in his twenties when this once non-religious farm boy embraced Methodism, eventually serving as an ordained minister and missionary to the Wyandot people.

The Civil War catalyzed his radical shift from spiritual guide to military leader. Rejecting a chaplain’s commission for combat, Chivington rose to prominence in the 1st Colorado Volunteers despite lacking formal training.

His military leadership at Glorieta Pass initially earned acclaim, but his command decisions culminated in the horrific Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, where his troops slaughtered and mutilated hundreds of peaceful Native Americans.

Though he escaped legal consequences, his actions forever tarnished his reputation and foreclosed his political ambitions.

The Sand Creek Massacre and Its Historical Context

Near the banks of Big Sandy Creek in southeastern Colorado Territory, one of the most heinous acts of violence against Native Americans unfolded on November 29, 1864. Colonel Chivington led 675 militia soldiers in an eight-hour assault on peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho camps flying white and American flags.

Despite proclaimed friendship with the U.S. government and promises of protection, these Native American communities faced indiscriminate slaughter.

The massacre occurred amid Civil War tensions and the Colorado Wars, targeting peace-favoring chiefs like Black Kettle. Between 70-230 people died—mostly women, children, and elders—with victims subjected to scalping and mutilation. The Treaty of 1861 had dramatically reduced Native lands to less than 1/13 of their original territory, fueling tensions prior to the attack.

This betrayal sparked retaliatory attacks throughout 1865 and profoundly damaged U.S.-Native relations, establishing cycles of violence that would persist for generations. Today, the Sand Creek National Historic Site established in 2007 commemorates this tragic event and honors the memory of the victims.

Daily Life in Peak-Era Chivington

During Chivington’s heyday, you’d find the railroad hub bustling with workers maintaining locomotives and loading agricultural products for transport across Colorado.

You could observe residents gathering at the Friends Church for worship services and community events, providing essential social cohesion in this frontier settlement.

The town’s brick schoolhouse and post office served as intellectual centers where information was exchanged, education provided, and connections to the broader world maintained.

Railroad Hub Activities

When Missouri Pacific Railroad established Chivington as a division point in the late 1880s, the settlement rapidly transformed into an essential transportation hub that orchestrated the rhythms of daily life for its 1,500 residents.

The combined freight and passenger depot anchored railroad commerce, serving as the nerve center where agricultural products from eastern Colorado were loaded for distant markets.

You’d have witnessed a flurry of activity as trains arrived and departed, dictating the town’s daily schedule. Railroad workers maintained tracks while immigrant cars delivered settlers with their household goods.

The alphabetically-named stop (part of Missouri Pacific’s marketing strategy) facilitated connections to Colorado Springs, Pueblo, and Denver.

This freight transportation network supported the Kingdon Hotel’s operations and the diverse businesses catering to travelers, creating an economic ecosystem entirely dependent on rail service.

Community Gathering Spaces

Daily life in Chivington during its prime revolved around a network of gathering spaces that fostered community cohesion despite the town’s transient railroad economy. You’d find residents congregating at the brick schoolhouse for education and civic meetings, while the Friends Church hosted religious services and life-milestone celebrations.

Both structures became symbolic anchors as commercial establishments diminished. The post office served as an information hub until 1991, where you could exchange news while collecting mail.

Railroad platforms became impromptu social stages during train arrivals, while saloons offered respite for working adults. Residential porches and the surrounding plains provided settings for neighborly interactions and seasonal social gatherings.

These community interactions persisted despite Chivington’s dark namesake and ultimate economic vulnerability, reflecting residents’ determination to create meaningful social bonds within their alphabetically-designated railroad stop.

Abandoned Architecture and Remaining Structures

The architectural remnants of Chivington stand as silent sentinels to the town’s bygone prosperity, offering invaluable insights into late 19th-century frontier construction techniques and spatial organization.

Architectural ghosts echo frontier dreams through weathered wood and crumbling brick facades

You’ll encounter a mixture of wooden and brick abandoned structures, each telling a unique story of frontier resilience. The wooden jail, constructed in 1882 with six-inch thick planks, represents law enforcement’s physical manifestation, while the red brick schoolhouse with its bell tower exemplifies civic aspirations despite its advanced architectural decay.

Most buildings exist in states of collapse—roofless walls and scattered brick piles marking where homes once stood.

The Queen Anne-style Kingdon Hotel, once a 60-room social hub, has been completely dismantled, leaving only historical records of its grandeur. These weathered ruins document the harsh realities of prairie abandonment.

From 1,500 Residents to Ghost Town Status

When you examine Chivington’s decline from its peak population of 1,500 residents, you’ll find the railroad’s departure delivered the decisive economic blow that accelerated abandonment.

The town’s remaining structures—dilapidated storefronts, collapsing homes, and crumbling civic buildings—function as physical artifacts documenting the community’s gradual dissolution throughout the early to mid-20th century.

Today’s Chivington exists as little more than a geographical designation, with only a handful of determined residents maintaining any semblance of habitation in what’s officially shifted to ghost town status.

Railroad Departure’s Fatal Impact

While Chivington initially thrived as a promising railroad boomtown with over 1,500 residents in the late 1880s, its precipitous decline began when the Missouri Pacific Railroad gradually diminished its operations in the area.

The roundhouse that once symbolized economic significance became obsolete as railroad consolidation swept through the industry, eliminating the need for numerous division points across the plains.

You can trace Chivington’s collapse directly to this withdrawal of railroad activity. Without rail traffic and associated employment, businesses shuttered one by one.

Economic fluctuations in agricultural markets compounded these problems, offering no alternative foundation for the community. The departure wasn’t marked by any catastrophic event—rather, it represented a slow economic strangulation that ultimately transformed a once-bustling commercial center into skeletal remnants of its former self.

Abandoned Buildings Tell Tales

Standing amid the scattered ruins of Chivington today, you’ll find it difficult to imagine that this desolate landscape once supported a vibrant community of 1,500 residents.

The architectural echoes of prosperity remain visible in the partially collapsed two-story Italianate schoolhouse, its rafters exposed to harsh elements that hastened the town’s abandonment.

The Friends Church stands as one of the few intact structures, while piles of bricks mark where homes and businesses once thrived. Ghost signs offering faint advertisements and political messages create ghostly whispers of commercial life.

These fragments tell a complex narrative of prosperity, environmental challenges, and ultimate desertion.

Archaeological surveys have documented foundations throughout the site, while highway markers and the TransAmerica Cycling Trail guarantee Chivington’s story persists despite its physical dissolution.

Few Residents Remain

The architectural remnants of Chivington tell only part of its story; the human exodus represents its most profound transformation.

Once home to a thriving settlement, Kiowa County’s population peaked at 3,786 in 1930 before the Dust Bowl triggered relentless community decline.

Today, you’ll find only a handful of souls where hundreds once lived. Economic challenges, including lost water rights and agricultural mechanization, have systematically driven residents away. The county’s population has dwindled to just 1,446, making it among Colorado’s least populated regions.

Young people particularly flee to urban centers, leaving behind an aging demographic with few resources. Rising living costs throughout Colorado, coupled with minimal local employment opportunities, accelerate this exodus.

What remains is primarily sustained by scattered dry-land farming operations—the last economic pulse in a place time has largely forgotten.

The Missouri Pacific Railroad’s Influence

As railroad expansion swept across the American West in the late nineteenth century, the Missouri Pacific Railroad (MoPac) emerged as a transformative force in Kiowa County, Colorado.

Through its subsidiary, the Pueblo and State Line Railroad, MoPac established 16 stops along 152.1 miles of track, with Chivington arising directly from this development in 1887.

The MoPac’s ambitious expansion birthed Chivington among 16 strategic stops spanning 152 miles of transformative western rail.

You’ll find the town’s very existence linked to H.S. Mallory’s alphabetical town naming strategy—executed by his daughter Jessie Mallory Thayer—which placed Chivington third in sequence from east to west.

The railroad’s arrival triggered immediate economic significance, with Chivington’s depot becoming among the region’s busiest in 1887-1888.

This infrastructure connected residents to major cities and facilitated the flow of goods, settlers, and opportunity—ultimately shaping the town’s brief period of prosperity before its eventual decline.

Preserving the Memory of a Controversial Past

While the Missouri Pacific Railroad’s alphabetical naming system may have mechanically designated “Chivington” as the town’s identifier, this seemingly innocuous choice carries profound historical weight that extends far beyond railway logistics.

When you visit this ghost town today, you’re confronting the legacy of Colonel John M. Chivington, whose leadership during the Sand Creek Massacre has sparked ongoing debate about appropriate memorialization efforts.

The establishment of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in 2007 represents a significant step toward historical reconciliation.

You’ll find Cheyenne and Arapaho descendants actively participating in annual commemorations, ensuring their ancestors’ stories aren’t forgotten.

The site’s educational programs challenge visitors to confront uncomfortable truths about our collective past—transforming what was once merely a town’s name into a catalyst for meaningful dialogue about historical justice.

Visiting Chivington Today: What Remains

When you venture to Chivington today, what exactly remains of this once-hopeful prairie settlement? The ghost town presents a stark tableau of abandonment: a deteriorating two-story Italianate schoolhouse with collapsed rafters stands sentinel alongside a solitary Friends Church amid scattered brick piles marking vanished structures.

Ruin exploration here reveals buildings slowly surrendering to time—partially collapsed walls, faded ghost signs referencing local elections, and prairie reclaiming former streets.

Though accessible via road and frequented by TransAmerica cyclists, amenities are nonexistent in this abandoned landscape.

Nature has largely reclaimed Chivington; birds and rodents inhabit crumbling edifices where humans once dwelled. The town’s physical dissolution mirrors its historical trajectory—a settlement undone by railroad departure, unsuitable water, and the merciless Dust Bowl that scattered its inhabitants across more promising horizons.

The National Historic Site: Remembrance and Reconciliation

Though Chivington town declined into abandonment, the area now hosts a site of profound national significance: the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. Established through Congressional action in 1998-2000, this 3,025-acre memorial stands as a symbol of memory preservation and cultural reconciliation.

You’ll find the site jointly managed by the National Park Service and Native tribes, with half the land held in trust for the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples. Their invaluable oral histories and traditional knowledge helped authenticate the massacre location, where archaeological investigations uncovered bullets and camp artifacts confirming historical accounts.

When visiting, respect that the actual massacre grounds remain off-limits to protect their sanctity. The site serves as a space for healing, education, and acknowledgment of historical atrocities against Native Americans.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Paranormal Activity Reports in Chivington’s Abandoned Buildings?

Deserted dwellings yield no documented data on paranormal presence. You’ll find no verifiable ghost sightings or unexplained noises reported in available historical records, scholarly sources, or visitor testimonials regarding these ruins.

What Happened to Residents’ Belongings When They Left Chivington?

You’ll find that residents’ belongings were largely abandoned in their homes. Most possessions remained behind, while others were looted, salvaged by neighbors, or weathered into ruins as economic necessity forced hasty departures.

Can Visitors Legally Explore and Photograph the Abandoned Structures?

You’re traversing legal ambiguity; exploration guidelines suggest obtaining property owners’ permission before entering structures. Photography permissions exist for public viewpoints, but private property requires consent to avoid trespassing violations.

Were Any Movies or Television Shows Filmed in Chivington?

Like faded ghosts of cinema dreams, no film or television productions have been documented in Chivington. The town’s haunting emptiness and cultural sensitivity deter filmmakers seeking ghost town film locations.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Visit Chivington Besides Colonel Chivington?

Beyond Colonel Chivington himself, you’ll find no documented evidence of other famous historical figures visiting the ghost town, despite its historical significance in relation to the nearby Sand Creek Massacre.

References

- https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2000/11/conscience-place-sand-creek/

- https://kiowacountyindependent.com/lifestyles/long-time-gone/5035-long-time-gone-stories-of-chivington-as-told-by-miss-mary-marble

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chivington

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/sandcreek.htm

- https://kiowacounty-colorado.com/chivington.htm

- https://5008.sydneyplus.com/HistoryColorado_ArgusNet_Final/ViewRecord.aspx?template=Object&record=32a1e890-e09f-44c2-8ec9-6a5aae011b48

- https://kiowacountyindependent.com/lifestyles/long-time-gone/1757-long-time-gone-and-the-abc-s-of-kiowa-county-railroad-towns

- https://kiowacountyindependent.com/lifestyles/long-time-gone/3584-long-time-gone-abcs-of-railroad-towns-in-kiowa-county

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Chivington

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Chivington