Chihuahua, Colorado emerged in 1880 as a silver mining boomtown with a population of about 200 residents. You’ll find it was devastated by a catastrophic fire in 1889 and the silver market crash of 1893, leading to its abandonment. Today, this ghost town exists only as subtle foundations and scattered artifacts on U.S. Forest Service land. Reaching the remote site requires 4-wheel drive vehicles or hiking through challenging mountain terrain—the forgotten settlement awaits intrepid explorers.

Key Takeaways

- Chihuahua was a silver mining town established in 1880 in Colorado’s Peru Creek valley.

- The town peaked at 200 residents with hotels, saloons, and a railroad connection by 1883.

- The Great Fire of 1889 destroyed approximately 50 buildings, devastating the settlement.

- Economic collapse followed when the silver market crashed in 1893, leading to abandonment.

- Today, only foundations and artifacts remain at the site, now protected by U.S. Forest Service.

The Rise of a Silver Boomtown (1880-1889)

The swift transformation of Chihuahua from barren mountainside to bustling silver boomtown began in 1880, when silver strikes in the Peru Creek valley lured ambitious miners to this remote Colorado location.

The rugged Peru Creek valley, once silent wilderness, echoed with pickaxes as silver fever transformed Colorado’s landscape overnight.

Named after Chihuahua, Mexico—not the dog breed—the settlement emerged with a methodical grid layout aligned with compass points, reflecting deliberate planning amid frontier chaos.

Mining techniques evolved rapidly as prospectors scrambled over Argentine Pass to access rich silver lodes.

Community dynamics flourished with the construction of approximately 54 buildings, including an exceptional school serving 24 students.

When the Denver, South Park & Pacific railroad arrived in 1883, transportation costs plummeted, accelerating both production and population growth.

At its peak, the town supported a modest population of about 200 people who built a thriving community with three hotels and three saloons to serve weary miners.

Despite the economic uncertainty of fluctuating silver prices, Chihuahua’s lively social scene and strategic development epitomized the freedom-seeking spirit that characterized Colorado’s silver boom communities.

Like many mining communities of the era, Chihuahua’s miners faced hazardous working conditions including the risk of silicosis and tunnel collapses as they extracted silver from the mountains.

Daily Life in a Mining Community

After a grueling shift in the Pennsylvania Mine, you’d return to Chihuahua’s modest dwellings where meals typically consisted of simple, hearty fare prepared from limited provisions transported into this remote mining settlement.

You’d gather with fellow miners at communal tables where food served as both sustenance and social glue, creating brief respites from the harsh realities of mountain mining life.

Your precious off-hours might include fishing in nearby streams, participating in community musical performances, or simply relaxing with neighbors in impromptu gatherings that strengthened the social bonds essential for survival in this isolated environment. Without paid sick days or benefits, many miners endured injuries and illness silently, knowing that missing work often meant losing their livelihood in this precarious economy.

Meals and Provisions

While miners toiled deep beneath the rocky earth of Chihuahua, their sustenance depended on a complex system of provisions that reflected the harsh realities of isolated mountain living.

You’d find your daily mining meals centered around energy-dense staples—flour, beans, and salted meats—transported over treacherous mountain paths at premium prices.

Food preservation techniques dominated daily life, with smoking, salting, and drying ensuring survival between infrequent deliveries.

You’d rise to hardtack and coffee before heading to your shift, returning to communal stews made from whatever supplies had survived the journey to this remote outpost.

Women managed these critical food operations while bartering systems flourished, with silver often exchanged for extra provisions.

When supplies ran short during harsh winters, you’d rely on community pooling and cooperation—a necessity for survival in Chihuahua’s unforgiving environment. Similar community cooperation was essential in Picacho, where approximately 700 workers depended on reliable food distribution during the mill’s peak operation.

The remoteness that challenged mining communities was particularly extreme in places like Platoro, situated at 9,842 feet elevation, where provisions had to be hauled over sixty miles of variable road conditions.

Leisure After Shifts

During those precious hours when the clanging of pickaxes and rumbling of ore carts fell silent, Chihuahua’s mining community transformed into a vibrant social ecosystem where exhaustion yielded to expressions of shared humanity.

You’d find yourself drawn to outdoor recreation after grueling shifts—fishing in nearby streams or hunting in surrounding forests. On Sundays, entire families gathered along arroyos, where children played in water while adults conversed under pine trees, birdsong replacing industrial cacophony.

These community gatherings transcended the rigid social hierarchies of working hours. Despite the company’s control over work schedules and housing arrangements, you created your own freedom through music, dance, and picnics that strengthened your social bonds.

Women organized these events, fostering the mutual aid networks essential to your survival in a place where formal benefits were nonexistent.

The Great Fire and Economic Collapse

You’ll find that Chihuahua’s fate was sealed by the catastrophic Great Fire of 1889, which razed approximately 50 buildings including essential businesses and community structures.

This disaster coincided with the devastating crash of the silver market, effectively eliminating the economic foundation upon which the entire community depended.

Unlike the resilient adobe structures found in the cliff dwellings of Sierra Madre, Mexico, Chihuahua’s wooden buildings offered little resistance to the flames.

Following these twin calamities, residents abandoned the town in a swift exodus, with no further elections held or taxes collected, ultimately leading to its formal cession to the U.S. Forest Service after more than a century of neglect. Elizabeth Rice Roller documented how her father and aunt saved their homes by using soaked quilts to protect their property during the fire.

Inferno Decimates Buildings

A devastating inferno swept through Chihuahua, Colorado, transforming this once-vibrant settlement into the ghost town you’ll find today. The blaze consumed nearly the entire townsite with frightening efficiency, leaving only ashes where homes and businesses once stood.

Without adequate fire prevention systems and facing dry climate conditions, the wooden structures succumbed rapidly to the flames. High summer temperatures and gusting winds accelerated the inferno’s path through the densely packed buildings. Similar to Chicago’s Great Fire of 1871, over two-thirds of structures were made of wood, contributing significantly to the fire’s intensity.

You’d have witnessed complete destruction as insufficient water supplies and limited firefighting equipment proved no match for the raging fire. The disaster echoed Colorado’s historical pattern where fire seasons typically occur between May and September, creating optimal conditions for rapid flame spread.

This catastrophe marked the beginning of Chihuahua’s demise, shattering community resilience as displaced residents permanently relocated. The economic foundation collapsed instantly, with reconstruction efforts abandoned amid overwhelming devastation.

Silver Market Crashes

While the great fire devastated Chihuahua’s physical structures, an equally destructive economic force had already begun undermining the town’s foundation.

The silver price collapse of 1893, triggered by the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, delivered a fatal blow to this mining community.

You’d have witnessed mining investment evaporate virtually overnight as silver’s value plummeted, rendering once-profitable ore worthless.

The Pennsylvania Mine and others drastically reduced production and shipping, eliminating jobs throughout the valley.

Credit dried up, businesses closed, and families departed.

This market failure exposed Chihuahua’s vulnerability to single-commodity dependence. Colorado, once reliant on its silver mining operations, faced economic devastation statewide as towns like Chihuahua collapsed.

Many migrated to Montezuma where conditions remained marginally better, leaving Chihuahua’s charred remains to slowly decay into the ghost town you can explore today.

Rapid Exodus Follows

As the embers of Chihuahua’s devastating fire still smoldered, an unprecedented exodus began that would transform the once-thriving mining settlement into a desolate ghost town within weeks.

You’d have witnessed entire families loading whatever possessions they’d salvaged onto wagons, fleeing the catastrophic destruction that had erased their economic foundation. This massive population displacement mirrored patterns seen in other disaster-stricken communities, where the combination of physical destruction and economic collapse made recovery impossible.

Local businesses, already weakened by the silver market crash, couldn’t absorb the additional shock of rebuilding costs. Despite attempts at community resilience through mutual aid societies and emergency shelters, the town’s infrastructure was too damaged to support even basic needs.

Military authorities established temporary order, but without commerce or services, Chihuahua’s remaining residents had no choice but to abandon their homes forever.

What Remains: Exploring the Ghost Town Today

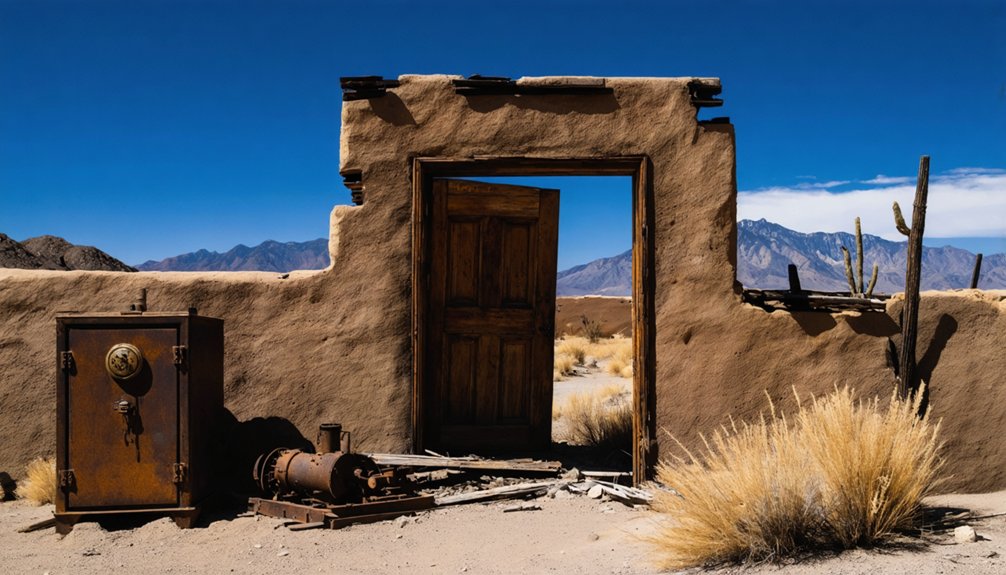

Today’s visitor to Chihuahua won’t find the bustling mining town that once thrived in this remote corner of Summit County, Colorado. Instead, your ghost town exploration requires a trained eye to detect the subtle clues scattered across the landscape—rock foundations of the former hotel, ground indentations marking cabin sites, and artifacts hidden among the grass.

The devastating 1889 fire and subsequent silver crash of 1893 erased virtually all structures, leaving only foundations and discarded debris as evidence of human presence.

For those seeking freedom in the backcountry, this unmarked site along Peru Creek Road offers dispersed camping opportunities, often directly atop the forgotten settlement. While hunting for artifacts, discovery might yield metal cans, glass shards, or rusty nails—mundane items that now tell the story of those who once called this remote wilderness home.

Notable Families and Town Governance

Though numerous families passed through Chihuahua during its brief existence, several notable households shaped the town’s development and governance structure. The Roller family established educational foundations, with Elizabeth’s grandmother teaching at the local school while her grandfather operated an essential boarding house for laborers.

Founding families like the Rollers laid Chihuahua’s cornerstone, establishing vital educational and housing services for the mining community.

Meanwhile, the Clancy family’s mine ownership positioned them as influential town developers.

Despite having formal township status with city officials, Chihuahua faced significant governance challenges. Officials rejected William Davis’s church proposal, suggesting secular priorities in the community’s leadership.

Family dynamics were further complicated by the economic dependency on mining, which proved devastating when the 1893 silver market crashed. The town’s inability to rebuild after multiple fires reflected inadequate infrastructure investment—a governance failure that ultimately contributed to Chihuahua’s abandonment, formalized through a Denver public hearing.

From Abandoned Town to Federal Land

The legal transformation of Chihuahua from ghost town to federally protected land represents a significant chapter in Colorado’s public land history.

After a decade-long negotiation, the town was officially abandoned under Colorado Revised Statute § 31-3-201, transferring ownership to the U.S. Forest Service.

You’ll find this shift particularly significant for its legal implications. The process involved public hearings and community testimony before concluding the abandonment petition.

Developer Gary Miller ultimately brokered a land swap, exchanging Chihuahua for 21 acres near Keystone Resort where “Dercum’s Dash” will host 24 new homes.

This arrangement prevented potential development of 500 residential units at the ghost town site. Under federal ownership, Chihuahua now enjoys protection against development, preserving its ecological value and historical significance within the National Forest system.

Accessing Chihuahua: Visitor Information

Reaching Chihuahua ghost town requires careful planning and appropriate transportation due to its remote location within federally managed land.

You’ll need a 4-wheel drive vehicle to navigate Peru Creek Road’s treacherous potholes and rocky terrain. Alternatively, hiking or joining guided historical tours provide safer transportation options for exploring this high-alpine relic.

- Feel the exhilaration of independence as you traverse unmaintained mountain roads that few modern travelers attempt.

- Experience the haunting solitude of standing where determined miners once sought fortune, now protected by federal stewardship.

- Embrace self-reliance by preparing all necessities—water, food, navigation—with no services available.

- Connect with Colorado’s rugged history through direct exploration, unfiltered by commercial development.

Visitor safety depends entirely on your preparation: sturdy footwear, layered clothing, and informing others of your plans before venturing into this cell-service dead zone.

Preserving Colorado’s Mining Heritage

As visitors traverse the challenging paths to Chihuahua, they’re participating in more than just an outdoor adventure—they’re witnessing a fragile historical resource that represents Colorado’s complex mining legacy.

Heritage conservation efforts face significant challenges with over 23,000 hazardous abandoned mine features throughout the state. The State Historical Fund has been instrumental, awarding $62.8 million for rehabilitation projects while leveraging $355.2 million in additional funding.

These preservation initiatives have generated nearly 35,000 jobs and $2.5 billion in economic impacts since 1981.

You’ll find mining education opportunities enriched by Colorado State Archives’ extensive collections documenting ownership, production, and labor statistics from 1900-1980.

When you explore ghost towns like Chihuahua, you’re supporting a preservation ecosystem that balances safety concerns with the imperative to maintain Colorado’s authentic mining narrative for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Any Famous Outlaws Known to Frequent Chihuahua?

No evidence supports outlaw legends or infamous figures frequenting Chihuahua. You won’t find documented criminal activity there as the town’s decline stemmed from economic factors and fire, not lawlessness.

What Indigenous Peoples Originally Inhabited the Chihuahua Area?

For thousands upon thousands of years, the Chihuahua region was home to diverse indigenous tribes including Apache (Chiricahua, Mescalero), Conchos, Tobosos, Tepehuán and Paquimé peoples, each contributing to the area’s rich cultural heritage.

Did Any Supernatural Legends or Ghost Stories Emerge From Chihuahua?

No documented ghostly sightings or haunted locations exist from Chihuahua. You’ll find no supernatural legends in historical records, memoirs, or oral histories—unlike other Colorado ghost towns with established paranormal reputations.

What Happened to Residents’ Personal Belongings After Abandonment?

Your ancestors’ personal belongings were likely consumed in the 1889 fire, with survivors taking valuables when fleeing. What remained deteriorated naturally or was scavenged—abandonment’s impact erased nearly all physical traces.

Have Any Valuable Artifacts Been Discovered by Modern Explorers?

You’ll find modest artifact significance in modern discoveries—mainly everyday items like metal cans, glass shards, and rusty nails, plus building foundations and grave markers, rather than highly valuable treasures.

References

- https://www.summitdaily.com/news/local/ghost-town-legally-abandoned-ceded-to-u-s-forest-service/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Colorado

- https://www.coloradolifemagazine.com/printpage/post/index/id/172

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Colorado

- https://gazette.com/?p=1082940

- https://www.gcc.com/books/ghost-mining-town/

- https://summithistorical.org/events/historic-hike-peru-creek-tour-with-interpretive-walks-at-the-chihuahua-ghost-town-and-pennsylvania-mine-with-ken-torrington/

- https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2683&context=nmhr

- https://www.summitdaily.com/news/chihuahua-colorado-ghost-town-summit-county-mining-history-peru-creek/

- https://www.summitdaily.com/news/born-of-mining-died-under-fire-chihuahuas-history/