Eastonville, Colorado was once a thriving agricultural community established in 1872, known as the “Potato Capital of the World.” You’ll find it tucked away in El Paso County, where the 1884 arrival of the Denver and New Orleans Railroad transformed this pioneer settlement. A devastating potato blight and the Memorial Day Flood of 1935 ultimately led to its abandonment. Today, stone foundations, an old passenger car, and the Eastonville Cemetery tell stories of resilience beyond Colorado’s famous gold rush towns.

Key Takeaways

- Eastonville was a once-thriving agricultural community in Colorado established in 1872, known as the “Potato Capital of the World.”

- The town declined after the Memorial Day Flood of 1935 and a devastating potato blight that ruined crops and forced families to abandon farms.

- Physical remains include crumbling stone foundations, the Eastonville Cemetery, and visible remnants of the Denver and New Orleans Railroad bed.

- Most ruins are on private property where trespassing is prohibited; visitors should stay on public roads and be aware of safety hazards.

- Unlike mining boomtowns, Eastonville represents Colorado’s agricultural pioneers and offers insights into early settler life and farming traditions.

The Birth of Easton: Early Settlement Years (1872-1880)

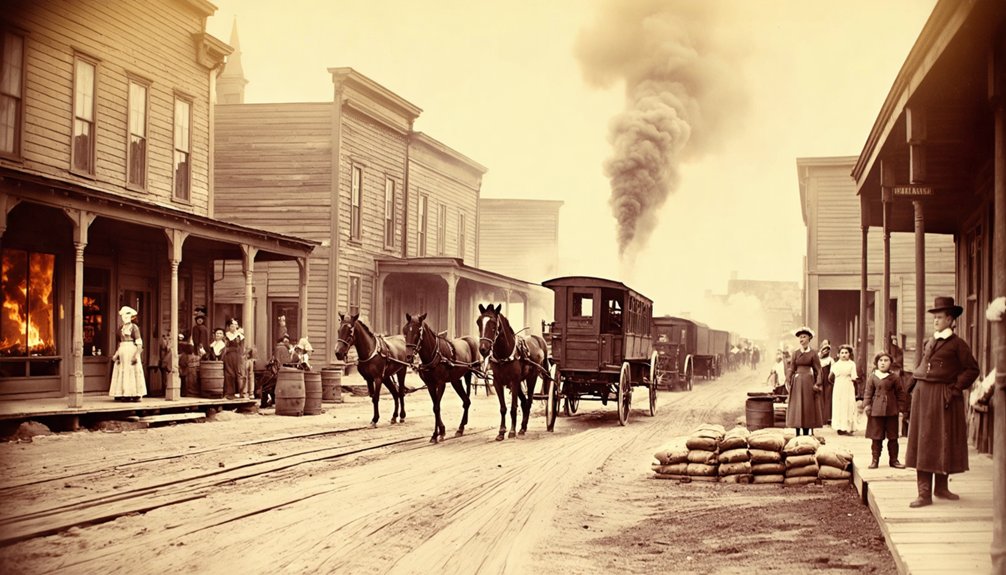

While the plains east of Colorado Springs appear barren to today’s traveler, they once cradled the humble beginnings of a thriving agricultural community. In 1872, pioneers established their homesteads in what would first be known as Easton, facing settlement challenges common to frontier life at the edge of the Black Forest.

Unlike neighboring boomtowns built on mining dreams, Easton’s identity took root in the soil. You’d have found families working the fertile Squirrel Creek Valley, where agricultural innovations in potato farming would eventually earn them a proud reputation. The name was later changed to Eastonville to avoid confusion with another Colorado town named Eaton.

The establishment of Weir’s Sawmill and a post office marked the community’s first official recognition, creating a gathering point for scattered homesteads. The need for railroad access would later prompt the community’s relocation in 1883, fundamentally changing its trajectory. Here, on the eastern frontier, freedom meant self-sufficiency and the promise of prosperity through honest labor.

Railroad Arrival: How Tracks Changed Everything

The whistle of progress echoed across the plains in 1881, forever altering Easton’s destiny.

When the Denver and New Orleans Railroad began laying tracks nearby, you’d have witnessed the dawning of a new era in local railroad history.

Facing a “relocate or perish” decision, residents voted to move their community to the McConnellsville train stop established in 1882.

This pivotal choice transformed the settlement into the “Potato Capital of the World,” with your grandparents’ generation shipping their harvests to distant markets previously unreachable.

The economic impact rippled through every aspect of life.

New stores appeared alongside the tracks, population swelled, and community gatherings flourished.

The Colorado Southern railroad became the lifeline that connected Eastonville to the rest of El Paso County and beyond.

The town officially became Eastonville on September 28, 1883, with John Brazelton serving as postmaster.

You’d have felt the palpable energy of prosperity—until the devastating 1935 flood washed away both tracks and dreams.

From Easton to Eastonville: The Critical 1884 Relocation

When the Denver and New Orleans Railroad established a stop at McConnellsville in 1882, you’d have witnessed Easton’s residents face a stark “relocate or perish” decision that would forever alter your community’s trajectory.

Your ancestors recognized that without proximity to these essential transportation arteries, the town’s agricultural prosperity—particularly its renowned potato farming—would wither as competing settlements with rail access flourished. This struggle was reminiscent of how Hays City’s designation as the railroad depot caused Rome, Kansas to lose its viability as a frontier settlement.

The momentous community vote in 1883 set the wheels in motion, culminating in 1884 with both the physical relocation of buildings and the official rechristening as “Eastonville”—a pragmatic move that temporarily secured your town’s place in Colorado’s agricultural landscape. Notable families like the Wilson family settled in the area during this transformative period, contributing to Eastonville’s development.

Railroad Spurs Growth

As tracks of the Denver and New Orleans Railroad stretched across the eastern Colorado plains in 1882, our humble settlement of Easton seized a crucial opportunity that would forever alter its destiny.

This railroad innovation connected you directly to Denver, Pueblo, Colorado Springs, and Falcon, transforming our town into a essential whistlestop.

The economic transformation was immediate and profound. Your potato farms, once limited to local markets, now shipped their harvests far and wide.

You proudly proclaimed Eastonville the “Potato Capital of the World” as the fertile soil yielded abundant crops.

Businesses sprouted alongside the tracks, schools and churches arose, and your community flourished.

The railroad breathed life into Eastonville for decades, carrying both your agricultural bounty and your dreams to distant horizons.

Move or Die Decision

While the railroad brought prosperity to many towns across the frontier, it presented your community with a stark ultimatum in 1883: relocate or fade into obscurity.

When the Denver and New Orleans Railroad established McConnellsville station miles from your homes, you faced a critical choice. The town vote revealed your ancestors’ wisdom—railroad influence wasn’t merely convenient but crucial for economic survival.

“Relocate or perish” became the rallying cry as neighbors packed entire buildings onto wagons, moving everything to secure essential rail access for your precious potato harvests.

The Potato Empire: Rise of an Agricultural Center

Nestled within Colorado’s Black Forest region, Eastonville transformed from humble beginnings into a self-proclaimed “Potato Capital of the World” during the late 19th century. The fertile soil and dry conditions yielded remarkably large potatoes, often weighing two pounds each, attracting homesteaders enthusiastic to claim their piece of this agricultural promise.

You would have witnessed freight trains departing daily, loaded with the town’s prized crop bound for distant markets and mining communities. Local pioneers celebrated their success through annual potato festivals and community bakes, reinforcing the bonds of shared prosperity. This agricultural success mirrored the achievements of Rufus Clark, who became wealthy through potato farming that supplied miners with this staple food.

The Eastonville creamery further enhanced the town’s reputation with its award-winning butter and cheese.

When the railroad arrived in 1881-1882, it cemented Eastonville’s position as a vibrant hub of potato cultivation and agricultural innovation that defined an era of rural Colorado prosperity. The Denver and New Orleans Railroad established a crucial transportation network that attempted to connect Colorado to southern markets, though it never fully reached its intended Gulf Coast destination.

Daily Life in Eastonville’s Heyday

During Eastonville’s golden era of the late 1880s, you’d have found a modest but vibrant community of 30-40 residents whose daily rhythms echoed the agricultural heartbeat of Colorado’s frontier life.

Your days would revolve around essential tasks—tending crops, maintaining homes heated by wood stoves and illuminated by oil lamps, drawing water from local wells.

The Little Red Schoolhouse anchored community bonds beyond education, hosting celebrations that brought families together.

You’d gather at the general store to exchange news and stories after completing daily routines.

When the train whistled through town, it meant jobs for some and supplies for all.

Multi-generational households worked together, with children balancing chores and basic schooling in a place where neighbors weren’t just acquaintances—they were your lifeline.

Like many other farming communities of its era, Eastonville eventually emptied as residents joined the massive rural migration to more populated areas.

The Devastating Memorial Day Flood of 1935

The peaceful rhythm of Eastonville’s community life came to an abrupt halt on Memorial Day 1935, when the skies opened with unprecedented fury. Within just four hours, a staggering 14 inches of rain transformed Monument and Kiowa Creeks into raging torrents, sweeping away homes, bridges, and lives.

You’d barely have had time to react as floodwaters rose with terrifying speed. The disaster claimed 113 souls throughout the region, with many residents watching helplessly as family members were carried downstream. Survivors later described in vivid detail the dramatic destruction of homes as structures were lifted from their foundations and carried away by the powerful currents.

Historical documentation records $26 million in damages—nearly $800 million in modern terms. Flood recovery efforts were hampered by destroyed infrastructure—341 miles of highways and 307 bridges gone.

This catastrophe, ranking among Colorado’s three worst floods, forever altered Eastonville’s destiny and shaped regional flood management for decades to come.

Agricultural Collapse: The Mysterious Potato Blight

Long before the devastating flood of 1935, Eastonville’s once-thriving agricultural economy faced a more insidious enemy: a mysterious potato blight that ravaged the town’s primary cash crop.

You might’ve heard whispers of how this disease, now known to be Phytophthora infestans, struck swiftly and mercilessly. Dark blotches appeared on leaves, white mold spread underneath, and precious tubers rotted into foul-smelling mush. The agricultural decline was devastating—entire fields withered within days.

The silent killer crept through the fields, turning prosperity to putrid waste as farmers watched helplessly.

Unlike today’s San Luis Valley with its protective quarantines, Eastonville had no defenses. The blight impact echoed Ireland’s tragedy from decades earlier, though on a smaller scale.

As crops failed, families struggled to recover investments. Many abandoned their farms, seeking opportunities elsewhere. Those who remained faced diminishing returns year after year, weakening the community’s economic foundation long before floodwaters washed away what remained.

The Final Exodus: How Eastonville Emptied

While potato blight weakened Eastonville’s agricultural foundation, it was the gradual unraveling of the town’s lifeline—the railroad—that ultimately sealed its fate.

As rail service diminished through the early 1900s, you’d have witnessed families quietly packing their belongings, surrendering to economic inevitability.

The town that relocated to embrace the promise of rail connection now suffered from its absence.

Despite remarkable community resilience, Eastonville’s limited economic adaptability proved fatal.

Young residents sought opportunities in Colorado Springs and Denver, leaving only the most determined behind.

What Remains Today: Exploring the Ghost Town Ruins

Wandering through what’s left of Eastonville today, you’ll encounter crumbling stone foundations along Sweet Road that whisper stories of our once-thriving community.

The weathered passenger car from the Pikes Peak and Manitou Cog Railway stands as a silent sentinel beside the old Colorado & Southern railroad bed, marking the transportation lifeline that once connected our town to the wider world.

If you’re planning to visit these fragile remnants, exercise caution around deteriorating structures affected by recent windstorms and roof collapses that have further endangered these precious links to our shared past.

Physical Remains Today

Though little remains of Eastonville’s once-thriving community, the ghost town’s physical remnants tell a poignant story of Colorado’s frontier past.

You’ll find the Eastonville Cemetery standing as the most intact historical marker, its weathered gravestones chronicling the lives of settlers who called this place home.

As you wander the area, scattered architectural remnants emerge from the pastoral landscape—fragments of stone buildings, decaying wooden cabins, and collapsed farm structures.

The curious presence of an old Pikes Peak Cog Railway passenger car sits isolated in a former town pasture.

Nature has reclaimed much of Eastonville, with invasive vegetation covering old foundations and windbreak tree lines occasionally marking former boundaries.

These quiet ruins, mostly on private farmland, whisper of dreams both realized and abandoned.

Railroad Evidence Persists

Despite the passage of time, evidence of Eastonville’s railroad heritage remains etched into the landscape for those who know where to look.

You’ll find the raised Denver and New Orleans Railroad bed visible on both sides of Sweet Road, a silent symbol to the town’s vibrant past.

In a nearby pasture rests a fascinating relic—an old passenger car from the Pikes Peak and Manitou Cog Railway, still showing traces of its original red “swoosh” and lettering.

These railroad remnants connect you directly to the era when Eastonville thrived as a regional hub, with nine daily passenger trains and busy freight operations shipping potatoes, grain, and dairy products.

The historical significance of these artifacts can’t be overstated—they’re tangible links to Eastonville’s golden age before trucks replaced trains and passenger routes were rerouted.

Visiting Safety Considerations

Today’s visitors to Eastonville encounter a vastly different landscape than the bustling rail center of yesteryear.

What remains lies mostly on private land, with serious safety hazards for the unprepared explorer. If you’re drawn to experience this fragment of our community’s past, remember that proper preparation honors both history and property rights.

When visiting, follow these essential visitor guidelines:

- Stay on public roads and never cross fences – most of Eastonville sits on private property where trespassing is prohibited.

- Bring water, wear sturdy boots, and carry a first aid kit – the remote location means help is far away.

- Observe from designated areas only – unstable structures, hidden debris, and wildlife pose genuine dangers.

Comparing Eastonville: Colorado’s Non-Mining Ghost Towns

Unlike most ghost towns dotting Colorado’s mountainous landscape, Eastonville stands as a tribute to the state’s lesser-known agricultural heritage rather than its mining boom.

While you’ll typically find abandoned mining towns throughout the Rockies, Eastonville’s story follows a different path.

The self-proclaimed “Potato Capital of the World” represents a vanishing piece of Colorado’s agricultural heritage.

Where other ghost towns feature collapsing mine shafts and ore processing equipment, you’ll find farm structures and railroad remnants along Sweet Road.

Eastonville’s decline came not from depleted mineral veins but from the slow migration away from rural communities.

As you explore Colorado’s non-mining communities, Eastonville reminds us that the state’s history extends beyond gold rushes to include the equally important story of its farming pioneers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Any Infamous Crimes or Outlaws Have Connections to Eastonville?

No, you’ll find no infamous outlaws or crime history associated with your ancestral Eastonville. The peaceful agricultural community’s legacy remains untarnished by the lawlessness that characterized many other frontier settlements.

What Happened to the Remaining Residents After Eastonville’s Decline?

Remarkably, just as dust claimed their homes, you’d find these families scattered throughout the Pikes Peak region, their residential migration creating a diaspora that preserved Eastonville’s community legacy through cemetery visits and shared memories.

Were There Any Notable Cultural or Ethnic Groups in Eastonville?

You’ll find little evidence of cultural diversity in Eastonville’s history. The community’s ethnic heritage appears mainly Euro-American, with no documented immigrant enclaves amid their cherished agricultural traditions.

What Was the Highest Recorded Population of Eastonville?

In a town that once hummed like a beehive, you’d find historical records showing Eastonville’s highest population reached approximately 500 souls around 1900, when community spirit and agricultural prosperity flourished together.

Did Eastonville Have Any Unique Local Traditions or Celebrations?

You’ll find Eastonville’s heart beating strongest during their annual potato festival, where community gatherings celebrated their agricultural pride. This signature local festival embodied their spirited identity as the “Potato Capital.”

References

- https://digging-history.com/2015/03/25/ghost-town-wednesday-eastonville-colorado/

- https://newfalconherald.com/eastonville-the-town-that-disappeared/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Colorado

- https://6100feet.com/2016/03/08/eastonville-co/

- https://freepages.history.rootsweb.com/~gtusa/usa/co.htm

- https://www.ebay.com/itm/306062668638

- http://coloradorestlessnative.blogspot.com/2013/08/eastonville-rich-in-history-ghost-town.html

- http://digging-history.com/tag/peyton-colorado/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Colorado

- https://5008.sydneyplus.com/HistoryColorado_ArgusNet_Final/ViewRecord.aspx?template=Object&record=de71a020-9c19-4a81-8309-c5bfdb2dd932