You’ll discover fascinating abandoned Western towns near the Grand Canyon, including Chloride, Arizona’s oldest living ghost town, and Cyanide Springs with its 1899 structures. These former mining communities offer glimpses into frontier life through preserved jails, saloons, and miners’ cabins. Visit between October and May for ideal conditions, and prepare for rough roads requiring high-clearance vehicles. The region’s rich mining history and authentic Western artifacts await your exploration beyond the canyon’s rim.

Key Takeaways

- Chloride, Arizona’s oldest living ghost town with over 300 residents, is accessible near the Grand Canyon.

- High-clearance vehicles are essential for reaching remote ghost towns, with October to May offering optimal visiting conditions.

- Historic mining towns like Jerome, Hackberry, Oatman, and Swansea showcase the region’s boom-bust copper and uranium mining history.

- Cyanide Springs features authentic Western frontier structures dating to 1899 and offers gunfight reenactments.

- Ghost towns near the Grand Canyon contain preserved jails, saloons, and cemeteries that tell stories of frontier life.

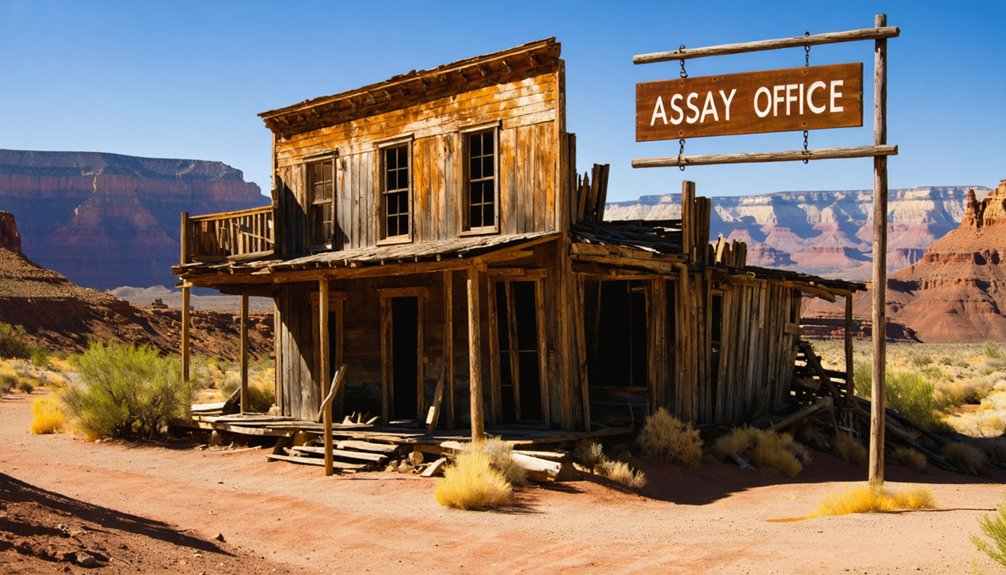

The Hidden Ghost Town of Cyanide Springs

Nestled in the rugged terrain of Chloride, Mohave County, Arizona, the ghost town of Cyanide Springs stands as a meticulously crafted replica of Western frontier life on the southwest flank of the Cerbat Mountains.

Constructed from reclaimed timber of the Golconda Mine, this living museum represents an authentic segment of the original settlement, with structures dating to 1899.

The Chloride Historical Society maintains this enchanting enclave, where you’ll discover the Dead Ass Saloon, jail, sheriff’s office, and four original miners’ cabins. The area was primarily known for its copper mining operations, which contributed significantly to the region’s development. This historic site offers visitors a glimpse into the once-thriving community that had over 2,000 residents during its peak mining era.

Explore a preserved slice of frontier history, where authenticity permeates every weathered plank and dusty corner.

The Jim Fritz Museum, open bimonthly, houses artifacts from the 1880s mining era.

During tourist season, you can witness spirited gunfight reenactments on Saturdays at high noon, performed by locals in period attire—a reflection of the region’s untamed past and the independent spirit that defined the American frontier.

When you set out to discover the forgotten settlements of America’s western frontier, be prepared to navigate more than just history—these journeys often demand traversing some of the most challenging terrain in the Southwest.

The rugged landscapes surrounding these time-capsules require planning beyond ordinary road trips.

- High-clearance vehicles are essential for unpaved paths to sites like Ruby, where ghostly legends persist among crumbling adobes.

- Weather dramatically transforms access routes—summer dust becomes impassable mud after desert rains.

- Fuel availability remains scarce; fill your tank before venturing beyond Route 66 remnants like Two Guns.

- Cell service disappears quickly in these remote areas, necessitating paper maps and compass navigation.

These physical challenges mirror the hardships faced by the pioneers whose footsteps you follow—making discovery all the more authentic. Visiting ghost towns like Cyanide Springs provides a unique exploration experience with typically no other visitors present to interrupt your journey into the past.

Unlike Goldfield, which is located just 4.5 miles northeast of Apache Junction on the historic Apache Trail, many abandoned towns are far more remote and difficult to access.

Mining Booms and Busts Near the Canyon’s Edge

While the journeys to abandoned towns test modern travelers’ resilience, the history that created these ghost settlements reveals an even more compelling saga of human ambition.

Standing at the canyon’s edge, you’re witnessing the aftermath of the 1872 General Mining Act that released prospectors’ dreams across this landscape. The boom cycle began with copper claims in the late 1800s, followed by uranium’s Cold War surge when over 8,000 claims surrounded the park by the 1950s.

These extractive rushes birthed communities like Grandview and Orphan, complete with ingenious infrastructure including tramways and trails you might still hike today. The Orphan Mine alone produced approximately 800,000 tons of uranium ore during its operational years.

The mining legacies persist in abandoned structures and environmental impacts—contaminated water sources and disrupted Indigenous lands. Bill Donelson’s Gray Dick Lode became part of this mining history when he staked his claim around 1920 just 1.3 miles south of the Grand Canyon.

These ghost towns embody both American resource extraction fervor and its inevitable busts when markets collapsed.

What Remains: Historic Structures of Arizona’s Abandoned Towns

Walking through Arizona’s ghost towns, you’ll encounter stark jail cells that once confined notorious outlaws and common drunks alike, their iron bars standing as silent witnesses to frontier justice.

The saloons’ architectural details—from ornate wooden bars to pressed-tin ceilings—reveal the surprising sophistication that existed even in these remote mining outposts. In Jerome, visitors can explore the infamous Spirit Room Bar that once served the thousands of miners who helped the town earn its “Billion Dollar Copper Camp” nickname. Many of these structures represent the harsh living conditions that characterized Arizona’s mining communities in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Cemeteries, perhaps the most poignant remnants, contain weathered markers bearing the names of miners, madams, and children, their epitaphs offering intimate glimpses into the harsh realities and fleeting joys of Western boom town life.

Old Jail Stories

Among the most compelling remnants of Arizona’s ghost towns, the historic jails stand as silent witnesses to frontier justice and lawlessness during the mining boom era of 1863-1921.

You’ll encounter fascinating jail anecdotes as you explore these weathered structures, from Jerome’s “sliding jail” that shifted downhill with the unstable ground to Clifton’s inescapable cliff-face cell.

- Gleeson’s 1910 jail, remarkably preserved despite decades of abandonment, served as a temporary holding facility before prisoners faced Tombstone’s justice.

- Courtland’s concrete jail remains among the most visible vestiges near Ghost Town Trail.

- Jerome’s copper-era facilities contain distinctive architectural elements of early 1900s prison design.

- Salt River Canyon’s tiny cell, built directly into a 1920s gas station, held transient troublemakers.

Some visitors report ghostly encounters within these austere walls. In Fairbank, the railroad stop established in 1881 features several adobe structures that housed local law enforcement during its heyday. Many of these structures are part of preservation efforts that allow the public to safely tour these historical sites.

Saloon Architecture Preserved

The weathered saloons of Arizona’s ghost towns narrate a different aspect of frontier life than their jail counterparts, showcasing the architectural ingenuity and social significance that once animated these mining communities.

These structures, with their distinctive high false fronts and decorative tin facades, represented social hubs where miners gathered after exhausting shifts.

You’ll find remarkable saloon preservation efforts throughout the state—from Cleator’s daily-operating establishment to Crown King’s original structure.

The architectural significance of these buildings lies in their adobe and wooden construction techniques, authentically maintained despite decades of abandonment.

In Gleeson, you can examine a partly collapsed saloon-store combination that reveals original building materials and methods.

The Arizona Land Project’s recent acquisition of Courtland properties demonstrates growing recognition that these saloons aren’t merely relics but irreplaceable windows into frontier society‘s commercial and cultural foundation.

Cemetery Tales Untold

Silent sentinels of forgotten communities, cemeteries often remain as the final physical evidence to Arizona’s vanished mining towns when all other structures have crumbled into dust.

These burial grounds embody profound cemetery symbolism, preserving forgotten histories through weathered markers and iron fences when mines closed and populations dispersed.

As you traverse these hallowed grounds, you’ll encounter:

- Congress’s divided burial grounds—testimony to the once-thriving dual communities of Mill Town and Lower Town

- Pearce Cemetery, situated along the historic military trail connecting Fort Bowie and Fort Huachuca

- Courtland Cemetery, outlasting the town’s mining infrastructure abandoned in the 1970s

- Tombstone’s cemeteries chronicling the violent demise of gunslingers and miners alike

These sacred spaces transcend mere burial grounds—they’re historical archives etched in stone, revealing societal hierarchies, migration patterns, and epidemics that once defined Arizona’s frontier communities.

Cemetery Tales: Stories Written in Stone

Weathered stone markers scattered across Arizona’s forgotten landscapes speak volumes about those who ventured westward during America’s ambitious frontier expansion.

You’ll find grave inscriptions that reveal not just names and dates, but entire life stories—miners crushed in collapsed shafts, gunslingers felled in dusty confrontations, and children claimed by frontier diseases.

These burial grounds hold profound historical significance as demographic records of boom-era populations.

At Chloride Cemetery, headstones with multilingual inscriptions evidence diverse immigrant communities, while Boothill Graveyard‘s 300+ graves include infamous outlaws from the O.K. Corral shootout.

When you visit these solemn grounds, you’re walking through unfiltered history, where segregated plots reflect societal divisions and unmarked graves silently testify to forgotten tragedies.

Each cemetery tells a uniquely American story of ambition, hardship, and ultimate sacrifice.

Weather and Isolation: The Atmospheric Experience of Ghost Towns

When approaching Arizona’s abandoned settlements, you’ll find yourself immersed in a sensory experience defined by extreme environmental conditions that both created and destroyed these frontier communities.

The isolation experiences intensify during weather patterns that transform these desolate landscapes:

- Cyanide Springs generates heightened atmospheric effects during precipitation, when rainfall amplifies the eerie quality of dilapidated structures.

- Winter months bring unexpected snow and rain that dramatically enhance the atmospheric quality of sites like Two Guns.

- Spring and fall offer moderate temperatures ideal for exploration, when the desert’s harsh extremes temporarily subside.

- Heavy rainfall events create hazardous conditions but reveal how water scarcity shaped these settlements’ ultimate abandonment.

The desert’s reclamation of human endeavor continues steadily, with foundations and ruins scattered across grasslands—testament to nature’s inevitable triumph over temporary occupation.

Photography Tips for Capturing Abandoned Western Architecture

Photographing abandoned frontier architecture demands technical precision that transcends typical landscape photography—where the interplay of harsh desert light, deteriorating structures, and historical narrative converge to challenge even experienced photographers.

For successful ghost town photography, employ bracketing techniques to balance the extreme contrast between sunlit exteriors and shadowed interiors. Position yourself against light sources to create natural diffusion similar to studio softbox effects. You’ll achieve best results during early morning or late evening, when raking light accentuates textural details of architectural decay.

Consider using prime lenses and tripods for sharper images in these challenging conditions.

Compositionally, keep your frames uncluttered—let diagonals and repeating patterns in weathered wood and rusting metal tell the structure’s story. Whether processing in vibrant color to suggest lingering energy or monochrome to emphasize melancholy, make sure your techniques align with the emotional narrative you’re conveying.

Route 66 Connection: Side Trips to America’s Mining Heritage

Your journey along Route 66 offers unprecedented access to America’s mining heritage through forgotten roadside detours where silver, gold, and copper once fueled Western expansion.

Towns like Oatman and Hackberry reveal a distinct boom-bust pattern where mining claims established settlements that later depended on automobile tourism for their second acts of prosperity.

When you explore these Route 66 adjacent mining communities, you’ll witness the layered history of Western development—from mineral extraction to transportation evolution—preserved in ghost towns that Interstate 40 eventually bypassed and left frozen in time.

Forgotten Roadside Detours

While Route 66‘s iconic status derives primarily from its role in America’s automotive culture, the historic highway also serves as a gateway to the nation’s rich mining heritage.

Veering off this forgotten highway reveals Arizona’s mining legacies preserved in towns like Hackberry, Oatman, and Two Guns. These detours offer authentic glimpses into America’s extractive past without contemporary commercialization obscuring their historical significance.

- Hackberry showcases the dual narrative of mining decline and Route 66 renaissance through its general store museum.

- Oatman’s wandering burros provide living connections to gold mining traditions.

- Swansea offers serious historians unvarnished access to copper processing infrastructure.

- Two Guns exemplifies the symbiotic relationship between mining economies and roadside tourism.

These overlooked destinations reveal how America’s westward expansion intertwined resource extraction with transportation networks, creating settlements that now stand as monuments to boom-and-bust capitalism.

Mining Heritage Trail

Beyond the well-worn asphalt of Route 66 lies a network of interconnected pathways collectively known as the Mining Heritage Trail, where America’s extractive past emerges through preserved headframes and company towns.

As you venture along this historical corridor, you’ll discover how the Mother Road served as a vital artery connecting mining communities across New Mexico, Kansas, and Missouri.

The Turquoise Trail near Tijeras offers exceptional ghost town exploration in Madrid and Cerrillos, where mining culture thrives in repurposed buildings and self-guided tours.

Further east, Galena, Kansas preserves its legacy in the Mining & Historical Museum, while Illinois towns like Gillespie showcase coal mining heritage.

These settlements—often with populations under 500—represent the economic foundation that preceded and ultimately supported Route 66’s development, creating a fascinating historical intersection of extraction and transportation.

Western Boom-Bust Patterns

As travelers venture off Route 66 into the sun-baked landscapes of the American Southwest, they encounter the physical remnants of America’s extractive past—a historical evidence to the dramatic boom-bust cycles that defined Western mining towns.

These ghost town economics follow predictable patterns, where mining community dynamics shifted rapidly from prosperity to abandonment.

You’ll witness these patterns in towns like:

- Jerome, Arizona—transforming from 15,000 residents to near emptiness after 1953

- Hackberry—revitalized briefly by Route 66 traffic after mining ceased in 1919

- Oatman—preserving its mining heritage within the stark Black Mountains terrain

- Swansea—offering authentic ruins of copper processing operations from 1910

These communities represent capitalism’s frontier edge—places where fortune and failure hinged on mineral veins, transportation accessibility, and economic forces beyond local control.

Beyond Cyanide Springs: Chloride and Oatman Ghost Towns

Nestled within Arizona’s rugged Cerbat Mountains, Chloride stands as the state’s oldest living ghost town, where the discovery of silver ore in the 1860s transformed a barren landscape into a thriving mining hub of 5,000 residents.

Unlike truly abandoned settlements, Chloride maintains over 300 inhabitants and America’s oldest continuously operating Arizona post office.

Defying ghost town stereotypes, Chloride breathes with 300 souls and houses Arizona’s longest-serving post office.

You’ll encounter Roy Purcell’s vibrant Chloride murals, painted in 1966 and restored in 2005, reflecting the region’s counterculture renaissance when artists and musicians revitalized the community after WWII mining decline.

The town’s preservation efforts include original miner cabins and Arizona’s only all-female gunfighting troupe performing historical reenactments.

For comparison, nearby Oatman offers a different abandoned mining experience, with wild Oatman burros—descendants of miners’ pack animals—freely roaming its preserved Western streets.

Planning Your Ghost Town Adventure: Practical Information

While preparing for a ghost town expedition across the American West requires careful planning, the rewards of experiencing these time capsules of frontier ambition justify the effort.

Ghost town access varies considerably—Cyanide Springs demands high-clearance vehicles for its dirt roads 23 miles north of Kingman, while Goldfield sits conveniently along the historic Apache Trail.

For ideal seasonal visits, consider:

- October through May offers the most comfortable temperatures and scheduled guided tours

- Early mornings or late afternoons mitigate summer’s punishing desert heat

- Winter precipitation may render dirt roads impassable at higher elevations

- Holiday closures affect some restored towns; verify operating hours beforehand

Carry cash for admission fees and bring essential supplies, as amenities become scarce the further you venture from established routes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Permits Required to Visit Cyanide Springs?

You’re in luck, freedom seeker! No permits required for Cyanide Springs—just show up on most Saturdays to immerse yourself in this historical gem’s Wild West ambiance. Mind your safety on uneven terrain.

Is Overnight Camping Allowed at These Ghost Towns?

No, you can’t camp overnight at ghost towns without a backcountry permit. Camping regulations require permits for preservation, while safety precautions mandate staying only in designated areas with proper authorization.

What Paranormal Activity Has Been Reported in These Locations?

You’ll encounter numerous documented ghost sightings at Jerome Grand Hotel, where 9,000 deaths occurred, while eerie noises plague Goldfield’s bordello. Indigenous Apache considered these areas “Devil’s Playground” due to persistent paranormal manifestations.

Can Artifacts Be Collected From Ghost Town Sites?

You cannot legally collect artifacts. Their historical significance demands in situ preservation. Taking items from federal lands near the Grand Canyon violates ARPA and potentially NAGPRA, risking severe penalties.

Are These Ghost Towns Accessible During Winter Months?

Winter accessibility varies greatly. You’ll find lower-elevation ghost towns remain navigable year-round, while northern and higher-elevation sites often require 4WD vehicles. Ghost town safety demands preparation for limited services and potentially hazardous road conditions.

References

- https://www.arizonahighways.com/article/arizona-ghost-towns

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/03/historic-old-west-towns-in-arizona.html

- https://goldfieldghosttown.com

- https://justsimplywander.com/ghost-towns-in-arizona/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q18D1sHH2Cc

- https://2dadswithbaggage.com/arizonas-old-west-by-car/

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g28924-Activities-c47-t14-Arizona.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NiiIhUGsW_M

- https://www.thetravel.com/barely-known-arizona-ghost-town-chloride-underrated-destination/

- https://nomadicniko.com/arizona/chloride/