You’ll find Gage twenty miles west of Deming, New Mexico, where it emerged as a silver-lead mining town in the 1880s. Under the leadership of investors George Hearst and James Ben Ali Haggin, the community grew to about 100 residents, supporting miners and their families. The town thrived around its railroad stop and trading post until the San Juan Extension’s closure in 1968. Today, only a simple traveler’s stop remains, though the surrounding desert landscape holds countless untold stories.

Key Takeaways

- Gage became a ghost town after thriving as a mining community in the 1880s, with silver-lead ore operations supporting about 100 residents.

- Located 20 miles west of Deming, New Mexico, along Interstate 10 and U.S. Route 70, Gage served as a vital transportation waypoint.

- The town’s decline accelerated after railroad service ended in 1968, leaving only a single traveler’s stop with service station remaining.

- Mining operations by investors George Hearst and James Ben Ali Haggin dominated the town before resource depletion led to economic decline.

- Desert conditions have reclaimed most structures, with ruins and foundations scattered across the landscape as remnants of the former community.

The Rise of a Desert Waypoint

As travelers crossed the harsh desert expanses of western Luna County, New Mexico, the small settlement of Gage emerged as a crucial waypoint along Interstate 10 and U.S. Route 70.

Located twenty miles west of Deming, you’ll find it nestled in a challenging landscape of sandy soil and hard-packed caliche clay. The distinctive ground composition of fine sand over caliche shaped the town’s development and accessibility.

Like Lake Valley’s early days as a booming mining town, Gage’s strategic position made it an essential hub for desert commerce, offering important services to those traversing the remote terrain.

You’ll appreciate how the town adapted to serve its purpose, establishing a trading post, gas station, and snack shop that became lifelines for weary travelers.

Among the sparse historic waypoints in this unforgiving environment, Gage’s development centered around supporting both passing motorists and local ranching and mining operations, creating a small but vibrant desert community.

Life in Early Gage

Life in early Gage revolved around the silver-lead ore mines that drew settlers to this remote desert outpost in the 1880s. The mining culture centered on tough work extracting valuable minerals, which were shipped first to Benson, Arizona and later to El Paso for processing. Much like early settlers who traveled the Santa Fe Trail, residents relied on established trade routes to transport their valuable mining products.

You’d find a close-knit community of about 100 residents at its peak, mostly miners and support workers adapting to the harsh desert environment.

- Notable investors George Hearst and James Ben Ali Haggin acquired major mining operations

- Daily life meant dealing with water scarcity and extreme weather conditions

- Community dynamics focused on shared labor and mutual support for survival

Despite the challenging conditions, the community’s spirit remained resilient until mining operations began to slow, eventually leading to Gage’s decline as residents sought opportunities elsewhere.

Geographic Features and Landscape

Located in western Luna County, New Mexico, Gage sits amid a stark desert landscape characterized by expansive plains and the dramatic Victorio Mountains rising 3 miles to the south.

You’ll find yourself surrounded by typical basin and range topography, where volcanic and sedimentary formations create a rugged terrain of ridges and valleys. Like other locations requiring proper navigation, clear pathways and markers help visitors safely explore the challenging terrain.

The area’s desert flora consists mainly of hardy, drought-resistant plants like creosote bushes, adapted to the region’s arid climate and temperature extremes.

While mining operations have left their mark through excavation sites and tailings, much of the natural environment remains intact. As with many of New Mexico’s ghost town sites, visitors must respect historical artifacts and leave them undisturbed.

You can spot native wildlife including mule deer and desert lizards, while birds like the phainopepla and canyon towhee soar above the geological formations that define this untamed landscape.

Transportation’s Role in Development

You’ll find that Gage’s initial development centered around the San Juan Extension narrow gauge railroad, which served as a critical water stop for steam locomotives between Chama and Durango. Like many places requiring disambiguation pages, the name Gage referred to multiple locations across the American Southwest.

After rail service ended in December 1968, Interstate 10 and U.S. Route 70 became the primary transportation corridors, transforming Gage from a railroad town into a highway travel stop.

Today’s road networks maintain Gage’s minimal remaining commercial activity, though they haven’t prevented its classification as a ghost town.

Road Networks Shaped Settlement

While New Mexico’s early settlements often grew organically around natural resources, the introduction of narrow-gauge railroads in the late 19th century dramatically reshaped the region’s development patterns.

You’ll find that towns like Tres Piedras, Chama, and Alcalde emerged directly along these crucial transportation corridors, their very existence tied to the rails that connected them to wider markets and essential resources. The Denver and Rio Grande played a pivotal role in connecting these communities and driving their growth.

- Transportation networks determined settlement locations, with communities clustering near accessible railheads.

- Ghost towns emerged when rail lines were abandoned, as seen in areas near Navajo Lake and Dead Junction.

- Mining operations, like those in Dawson, created concentrated settlements along rail routes designed for resource extraction.

The relationship between these rail lines and settlement patterns became especially clear when towns declined after losing their transportation lifelines, demonstrating how infrastructure shaped community survival.

Travel Stop Evolution

As stagecoach lines established regular routes through New Mexico in 1849, they created the first organized network of travel stops that would shape the region’s development for decades to come.

You’d find these early travel stops serving as essential hubs of historical commerce, where passengers paid $200 for two-week journeys that included basic amenities like blankets.

By 1858, freight traffic had exploded, with nearly 2,000 wagons hauling $3.5 million in goods.

When railroads arrived in 1878, they transformed travel infrastructure completely.

You’ll see how the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway sparked “New Town” developments with modern depots and hotels.

Later, specialized railways served remote logging and mining operations, until highways eventually replaced many rail corridors, adapting old travel stops for automobile traffic.

The narrow-gauge lines through the mountainous terrain required innovative engineering solutions to overcome the challenging landscape.

The establishment of Fort Union in 1851 provided crucial protection for travelers and merchants along the Santa Fe Trail.

Interstate Impact Assessment

The construction of Interstate 10 through western Luna County brought both promise and peril to Gage, New Mexico.

While the highway initially positioned the town as a strategic stop along a major transportation corridor, it ultimately accelerated the area’s shift toward ghost town dynamics.

You’ll find that interstate commerce patterns shifted dramatically, as faster vehicles and fewer stops became the norm, leading to a stark decline from 102 residents in 1930 to today’s sparse population.

- The interstate’s efficiency reduced the need for frequent traveler stops

- Nearby cities like Deming centralized regional commerce

- Local businesses couldn’t sustain themselves on diminished highway traffic

Today, you can see Interstate 10’s double-edged impact through Gage’s lone remaining business – a service station catering to passing travelers, standing as proof to how modern transportation infrastructure can reshape small town destinies.

The Town’s Gradual Decline

Located in Luna County, New Mexico, Gage experienced a steady decline that spanned several decades of the 20th century. By 1930, the population had already dwindled to just 102 residents, marking the beginning of a prolonged economic decline.

You’d have witnessed community shifts as businesses closed and structures deteriorated, with most buildings eventually being razed.

The town’s fate was sealed by multiple factors: the depletion of nearby mining resources, shifts in transportation routes, and the absence of alternative industries to sustain growth.

When Interstate 10 diverted traffic away, Gage lost its relevance as a traveler’s stop. By the latter half of the century, only minimal facilities remained – a service station and snack shop serving the occasional passerby, leaving behind another indication to the changing American West.

Modern-Day Remnants and Legacy

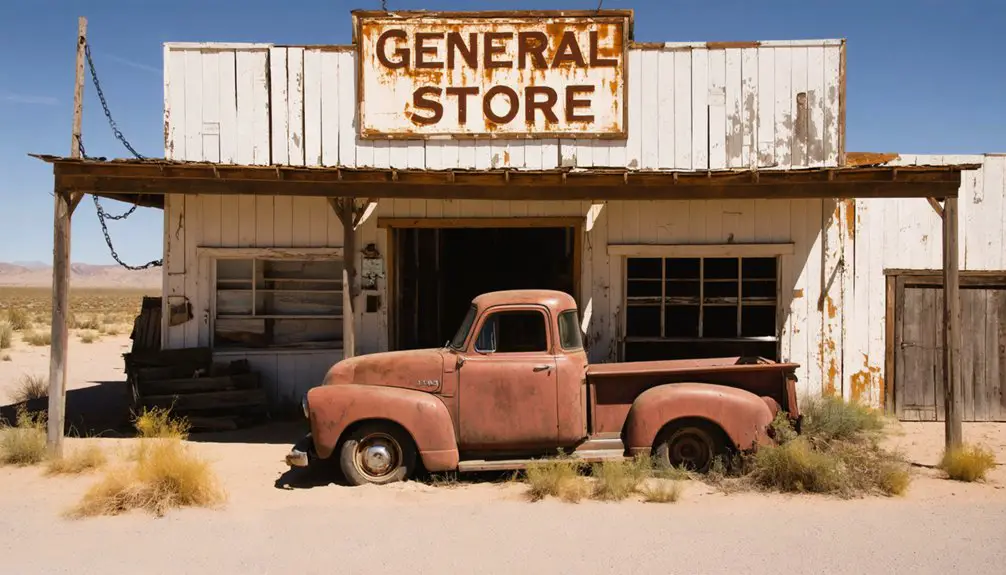

You’ll find scattered ruins of buildings and foundations dotting the desert landscape where Gage once stood as a bustling transportation hub, with rusted mining equipment partially buried in the sandy soil.

The site’s remote location requires careful navigation through desert terrain, making it accessible mainly by off-road routes that were once well-traveled railway corridors.

Nature has begun reclaiming the area, as native desert vegetation grows among the weathered remnants, creating an atmospheric blend of human history and natural preservation.

Present-Day Site Features

Modern-day Gage stands as a sparse collection of remnants along Interstate 10, where a single traveler’s stop with a service station and snack shop marks what was once a thriving railroad community.

You’ll find scattered ruins and foundations throughout the area, offering glimpses into the town’s past. While there aren’t any maintained historical buildings, the site’s accessibility makes it an intriguing stop for ghost town enthusiasts and road travelers.

abandoned buildings in Tyrone, New Mexico can be found nestled among the desert landscape. The eerie silence and crumbling structures beckon explorers looking to uncover the stories that lie within their walls. Each visit provides a unique opportunity to reflect on the town’s history and the lives that once filled its streets.

- Abandoned structures and partial walls provide opportunities for photography and historical exploration

- Easy highway access lets you visit the site while traveling between major Southwest destinations

- The surrounding desert landscape remains untouched, offering authentic views of the American frontier

The area’s proximity to the border means you might encounter Border Patrol presence, and limited infrastructure means planning ahead for basic amenities.

Transportation Hub Evolution

While today’s visitors see only scattered ruins, Gage once bustled as a key stop along the San Juan Extension of the narrow gauge railroad network between Chama, New Mexico, and Durango, Colorado.

The railroad economics of the early 20th century made Gage essential for both passenger service and freight transport, supporting local mining and ranching operations.

As transportation innovations evolved, the narrow gauge lines couldn’t compete with diesel engines and highways.

By December 1968, the last train rumbled through the area. You’ll now find most of the tracks removed or buried under years of sediment.

Though Gage’s rail infrastructure has vanished, you can still experience the region’s railroad heritage on the Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad, which preserves a portion of the historic Denver & Rio Grande right of way.

Desert Landscape Preservation

Despite decades of harsh desert conditions, Gage’s sole remaining structure – a simple traveler’s stop with a service station and snack shop – stands as the last physical reminder of this once-thriving railroad community.

The site’s desert conservation challenges reflect a common pattern among New Mexico’s ghost towns, where extreme temperatures and windblown sand continuously reshape the landscape. In its historical context, Gage represents the delicate balance between human settlement and nature’s reclamation.

Exploring Glenrio’s ghost town history reveals the stories of those who once thrived in this arid environment, highlighting both their struggles and triumphs. The remnants of structures and artifacts serve as poignant reminders of a community that has long since vanished, inviting visitors to contemplate the harsh realities of life on the edge of the desert. As the sands shift, they carry with them the echoes of a past that is both fascinating and haunting.

- Intense solar radiation and sand abrasion accelerate the deterioration of any exposed materials

- The arid climate has erased most traces of the town’s mining and residential structures

- Desert winds both protect lower ruins through burial while wearing down exposed surfaces

You’ll find Gage’s story primarily preserved through photographs and written accounts rather than physical remains, making it an illustration of the desert’s transformative power.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Indigenous Peoples Originally Inhabited the Area Around Gage?

While exact boundaries aren’t certain, you’ll find that Ancestral Puebloans first inhabited the region until 1300 AD, followed by Apache tribes who established themselves in the surrounding mountains and plains.

Were There Any Major Disasters or Incidents That Contributed to Gage’s Abandonment?

You won’t find any major natural disasters that caused the town’s abandonment – instead, it experienced a gradual economic decline as residents moved away, with the population steadily shrinking after 1930.

What Was the Average Property Value in Gage During Its Peak?

You’d be hard-pressed to find a real estate agent bragging about Gage’s property market! Given the historical economy and tiny peak population of 102, average values were likely minimal during the 1930s.

Did Any Notable Outlaws or Historical Figures Pass Through Gage?

While outlaw legends circulate through the region, you won’t find direct proof of notable figures visiting here. The closest historical travelers were Black Jack Christian’s gang, who robbed nearby Separ in 1896.

What Happened to the Families Who Lived in Gage After It Declined?

You’ll find families’ migration led to a 20-mile eastward shift, with many settling in Deming. Records show residents gradually dispersed between the 1920s-1950s, though community memories lived on through descendants.

References

- https://www.offexploring.com/pats-virtual-run-across-america/blog/new-mexico/separ

- https://www.whiteoaksnmgoldrush.com/gage-new-mexico-memoirs/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gage

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Gage

- https://newmexicotravelguy.com/new-mexico-ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O_1iT_a-Wzw

- http://northwestrocks.blogspot.com/2015/09/chance-city-ghost-town-new-mexico.html

- https://www.emnrd.nm.gov/mmd/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/Gage-nomination.pdf

- https://online.nmartmuseum.org/nmhistory/geography-and-environment/environmental-issues/settlement-issues/historytext-settling-the-land.html

- https://dn790007.ca.archive.org/0/items/illusthistnewmex00lewirich/illusthistnewmex00lewirich.pdf