You’ll find several authentic ghost towns within minutes of Virginia City, each preserving distinct chapters of the Comstock Lode’s history. Gold Hill sits just south with crumbling mine structures and Cornish miner cottages, while Silver City—Nevada’s best-preserved mining camp—retains original 1860s buildings along the old freight route. American City exists only as survey stakes marking a failed capital speculation, and Lousetown’s foundations trace the notorious toll-road station known for illegal gambling. These sites reveal the mining boom’s complete story beyond Virginia City’s tourist district.

Key Takeaways

- Gold Hill, a former mining town with 8,000 residents, features the historic Sutro Tunnel completed in 1878.

- Silver City preserves original 1860s buildings and served as the main freight stop between Comstock mines and mills.

- American City was a speculative capital project abandoned in the 1860s, now marked only by survey stakes.

- Lousetown operated as a notorious toll road station known for illegal gambling and boxing beyond law enforcement reach.

- Historic cemeteries, abandoned mills, and 117 toll road franchises offer additional ghost town exploration opportunities near Virginia City.

Gold Hill: A Living Relic of the Comstock Lode

When prospectors stumbled upon gleaming veins of silver and gold in early 1859, they couldn’t have known they’d triggered one of the most spectacular mining rushes in American history. Gold Hill’s heritage began with these discoveries that spawned the legendary Comstock Lode.

Within months, nearly 1,300 fortune-seekers flooded the canyon, establishing a gritty industrial center that contrasted sharply with neighboring Virginia City’s opulence.

Mining community dynamics shaped every aspect of life here. You’ll find evidence of the primarily working-class population—Cornish miners who carved out 8,000 lives at the town’s peak.

The Cornish miners and working-class families who built Gold Hill created a tight-knit community of 8,000 souls at its peak.

Though prosperity crashed after the Big Bonanza years ended, sporadic operations prevented total abandonment. The town’s post office operated continuously until 1943, serving the remaining residents long after the mining boom subsided.

The Sutro Tunnel, completed in 1878, provided crucial drainage and ventilation for the underground mines, though it never served as a significant ore removal route.

Today, you can explore restored buildings and ride the historic Virginia & Truckee railroad through this authentic remnant of America’s mining frontier.

Silver City: Nevada’s Best-Preserved Mining Town

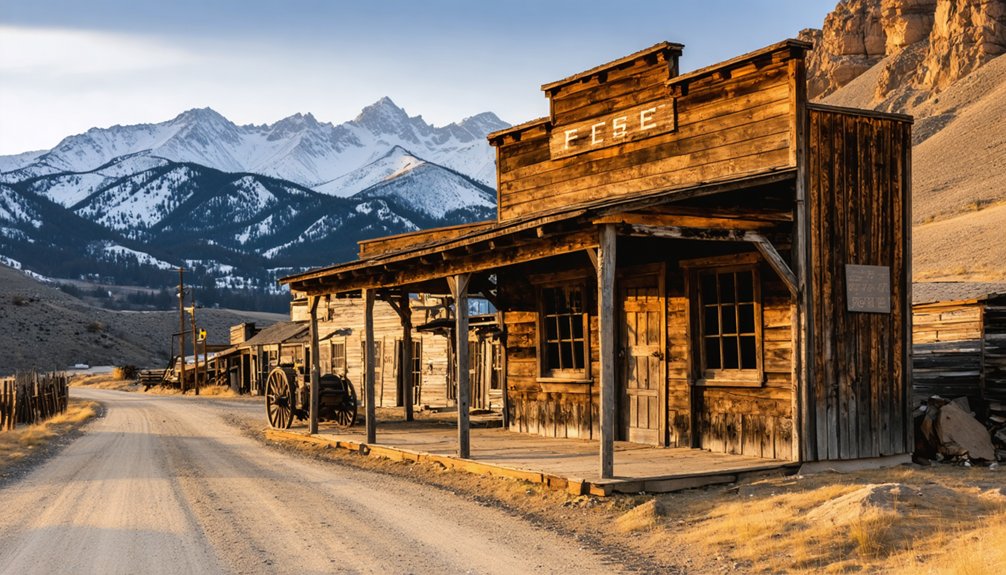

Tucked into Gold Canyon between Virginia City and Dayton, Silver City stands as Nevada’s most authentic surviving Comstock settlement—a place where preservation hasn’t required reconstruction.

You’ll walk past original 1860s stone buildings and wooden structures that genuinely housed the 1,200 residents who made this the main freight stop between Comstock mines and Carson River mills.

Unlike sanitized tourist sites, Silver City’s historical preservation reflects organic survival—hotels, saloons, and Virgin Alley’s red-light district remain where silver mining commerce actually occurred.

The town incorporated in December 1862 to maintain its independence, hosting Nevada’s first iron works and pioneering stamp mills that processed Comstock ore.

The completion of the Virginia and Truckee Railroad in 1869 stripped Silver City of its vital freight business, though mining operations continued for decades afterward.

Located 11 miles northeast of Carson City, the settlement’s position made it vulnerable to the highway robberies that plagued travelers at Devil’s Gate during its boom years.

Today’s quiet streets let you experience an unvarnished mining town where authenticity trumps spectacle, offering freedom to explore history without manufactured nostalgia.

American City: The Capital That Never Was

While Silver City survived through genuine commerce and community, not every Comstock-era settlement could claim the same fortune—some vanished before they truly began.

You’ll find American City among Nevada’s most ambitious failed visions, a capital that existed only on paper. Speculators platted this townsite nine miles northeast of Virginia City during the 1860s, banking on political maneuvering to relocate Nevada’s territorial seat from Carson City.

They promised broad avenues, government precincts, and rail connections—classic speculative dreams designed to attract investors. Promoters lobbied legislators with lot offers and strategic positioning between mining camps and agricultural valleys.

When Carson City’s established infrastructure and political networks prevailed, American City’s backers abandoned the scheme entirely. The pattern echoed across Nevada, where towns like San Juan, established in 1862, were quickly abandoned when mining prospects failed to materialize.

Nevada houses over three hundred ghost towns, each offering unique insights into the state’s boom and bust cycles. Today, you’ll discover nothing but survey stakes and faint traces where Nevada’s alternate capital might’ve stood.

Lousetown: Virginia City’s Notorious Northern Neighbor

North of Virginia City, you’ll find the remnants of Lousetown scattered along the old Washington Toll Road, where a bustling station stop once served miners traveling between the Truckee River and the Comstock Lode.

This settlement earned its reputation as Virginia City’s shadowy counterpart, hosting illegal boxing matches and rigged gambling operations that couldn’t operate in the more regulated mining city.

Despite its seedy reputation, the town’s name actually came from Louisa Town, not from any infestation of lice as some might assume.

Today, crumbling foundations and sections of the original toll road mark where this notorious ten-year community thrived before Geiger Grade‘s construction drew traffic away and left Lousetown to the sagebrush.

Halfway up the toll road sat the settlement of Washington, offering travelers services including horse changing stations, a hotel, restaurant, and saloon.

Station Stop and Origins

Serving as a critical junction where multiple toll roads narrowed into a single artery toward Virginia City, Lousetown emerged in the early 1860s as more than a simple waypoint—it became the Comstock’s northern gateway.

The station significance grew from its location on Orleans Flat, where freight teams and passenger traffic converged before the final climb south.

The historical evolution unfolded through three distinct phases:

- 1863–1864: Transformation from crude toll-road stop into Nevada’s largest weigh station and toll house complex

- Naming change: “Louisa Town” honored a prominent local resident, later shortened to “Lousetown”—not derived from infestation as myths suggest

- Peak operations: Wagon repair shops, stock facilities, and toll collection served the working-class suburb that housed teamsters, loggers, and sheepherders priced out of Virginia City proper.

The town featured amenities including a telegraph line, saloons, and a race track that enhanced its appeal to the growing community of workers seeking affordable housing alternatives. Many of Lousetown’s residents were Cornish and Irish immigrants who contributed to the mining operations while living in this more affordable northern settlement.

Illegal Gambling and Sports

Beyond Virginia City’s formal boundaries, Lousetown transformed into the Comstock’s preferred venue for activities banned within the main camp’s jurisdiction.

You’ll find this northern outpost gained notoriety for rigged faro tables, crooked card games, and illegal boxing matches that drew miners and teamsters seeking entertainment outside official oversight. The settlement’s racetrack became a focal point for wagering, trap shooting, and sporting competitions that Virginia City’s ordinances wouldn’t permit.

Lousetown’s gambling culture thrived because it occupied a legal gray zone along the toll roads. Distance from courts and law enforcement created space for these illegal activities to flourish openly.

The combination of wagon services and vice economy turned this roadside stop into a multi-purpose destination where Comstock workers could gamble, bet on races, and watch forbidden fights—all beyond reach of territorial authorities enforcing stricter controls downtown.

Remains Along Toll Road

These remnants offer direct access to authentic mining-era transportation infrastructure without modern interference.

Historic Cemeteries and Burial Grounds of the Comstock

The discovery of gold and silver on the Comstock brought thousands of fortune-seekers, but it also brought death in abundance—from mining accidents, disease, and the harsh realities of frontier life.

The Comstock lode promised riches but delivered death—mining disasters and disease claimed as many lives as silver enriched.

Silver Terrace Cemetery, established in the 1860s when earlier burial grounds proved too remote, sprawls across windswept terraces north of Virginia City.

You’ll find Victorian-era cemetery architecture throughout—nearly every plot fenced, markers crafted from wood, metal, and cut stone.

The segregated sections reveal society’s divisions: separate plots for different races, classes, and fraternal organizations like the Masons and Knights of Pythias.

What makes this necropolis remarkable are the immigrant stories etched on headstones—birthplaces from across the globe documenting the cultural melting pot that fueled America’s largest silver strike.

Toll Roads and Mountain Stations of the Mining Era

When fortune-seekers flooded the Comstock in 1859, they faced an immediate crisis: no engineered roads connected the remote lode to California’s supply depots or Nevada’s agricultural valleys.

Between 1861 and 1864, Nevada’s territorial legislature granted 117 toll road franchises, transforming mining transportation through private capital. Entrepreneurs blasted routes through steep terrain, replacing boulder-strewn mule trails with graded wagon roads capable of handling 10–15 ton freight rigs.

Key toll road infrastructure included:

- Geiger Grade – the direct but treacherous route from Truckee Meadows, with icy segments that never saw winter sun.

- Lake Tahoe Wagon Road – a 101-mile engineered thoroughfare requiring $500,000 investment from Placerville.

- Virginia Turnpike – the main artery from Marysville before the transcontinental railroad arrived.

Toll houses dotted strategic junctions, collecting $2 per wagon while providing essential roadside services.

Abandoned Mills and Processing Sites Along the Lode

Transporting ore to market represented only half the logistical challenge—miners still needed facilities to transform rock into bullion.

You’ll find the most dramatic example at American Flat, where massive reinforced-concrete shells mark one of America’s largest cyanide-processing plants. Built in 1922, this complex processed 2 million tons of low-grade Comstock ore through five ball mills and sophisticated leaching circuits before silver prices collapsed in 1926.

Concrete monuments to industrial ambition—processing millions of tons through ball mills and leaching circuits before economics ended the operation.

The abandoned structures stood for nearly ninety years—stripped of machinery, weathered by desert winds—until demolished in 2014.

Downriver at Dayton, industrial ruins of dozens of 19th-century stamp mills line the Carson River, their stone foundations testimony to the hydraulic infrastructure that once powered the Comstock’s extraction economy before environmental regulations and depleted veins silenced the machinery.

Planning Your Ghost Town Tour From Virginia City

How do you maximize your exploration time when dozens of mining camps and mill sites sprawl across the Comstock slopes? Smart ghost town logistics begin with route planning from Virginia City as your hub.

Sample itineraries for independent exploration:

- Half-day circuit — Drive SR-342 south through Gold Hill to Silver City (3–4 miles), exploring preserved buildings and brewery remnants before returning via the same route.

- Full-day loop — Combine Silver City, American City ruins downhill toward Carson, and the Old Catholic Cemetery, balancing driving segments with foundation walks and gravesite photography.

- Extended venture — Add Lousetown’s northern racetrack site via unpaved roads, checking conditions first.

Vehicle recommendations favor high-clearance SUVs for dirt access roads, especially during snow season or summer storms when Geiger Grade becomes treacherous.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Best Time of Year to Visit Ghost Towns Near Virginia City?

You’ll find the best season is late spring through early fall, when weather conditions deliver reliable road access to remote sites. Summer’s extended daylight lets you explore multiple ghost towns while dirt roads remain passable and photography opportunities flourish.

Are Any Ghost Town Sites on Private Property Requiring Permission to Enter?

Yes, many ghost town sites rest on private property requiring permission before you enter. Mining claims, ranch parcels, and commercial attractions around Virginia City demand you respect ownership boundaries and secure explicit consent to explore legally.

How Far Is Virginia City From Reno and Carson City?

You’ll find Virginia City just 20 miles from Reno—a scenic 40-minute drive via Highway 341’s challenging grades—while Carson City sits 30 minutes downhill. These distance landmarks and travel routes preserve your independence exploring Nevada’s authentic past.

What Should I Bring When Exploring Ghost Towns in This Area?

Pack essential gear including one gallon of water per person, sturdy boots, topographic maps, first-aid supplies, and sun protection. Prioritize safety precautions like sharing your itinerary, wearing high-visibility clothing, and avoiding unstable structures throughout Nevada’s historic mining districts.

Can I Take Artifacts or Souvenirs From Abandoned Ghost Town Sites?

No, you can’t legally take artifacts—federal ARPA laws, Nevada statutes, and local ordinances protect these sites. Beyond legal considerations, preservation ethics demand we leave historical evidence intact so future generations can understand our past.

References

- https://www.realgirlreview.com/virginia-city-nevada-ghost-town/

- https://nvtami.com/2025/01/22/virginia-citys-forgotten-ghost-towns/

- https://www.alllaketahoe.com/virginia_city_attractions/silver_city_ghost_town.php

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yjomCNEvkEk

- https://travelnevada.com/ghost-town/

- https://destinationyellowstone.com/day-trip-ghost-towns-virginia-nevada-city-montana/

- https://nvtami.com/2021/10/18/virginia-city-less-known/

- https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/nevada/gold-hill/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comstock_Lode

- https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84022046/