Texas ghost towns like Terlingua, Thurber, and Glenrio offer windows into the boom-and-bust cycles of the American frontier. You’ll discover mercury mines, coal operations, and strategic commercial outposts that once thrived before succumbing to resource depletion, market shifts, and transportation changes. Today, these weathered remnants face preservation challenges from remote locations and deteriorating infrastructure. Exploring these skeletal communities requires both determination and respect for the delicate balance between accessibility and conservation.

Key Takeaways

- Texas ghost towns like Shafter, Terlingua, and Thurber thrived through silver, mercury, and coal mining before declining due to resource depletion.

- Terlingua produced 40% of America’s wartime quicksilver before mercury demand evaporated, leading to abandonment by 1946.

- Towns like Glenrio collapsed when infrastructure changes, such as Interstate 40’s completion in 1973, bypassed their economic lifelines.

- Preservation efforts include historical markers, cemetery maintenance, and partnerships with academic institutions to document these abandoned settlements.

- Visitors can engage with ghost town history through community-led events while respecting private property and fragile structures.

The Rise and Fall of Terlingua’s Mercury Mining Empire

Mercury, the liquid metal that once fueled Terlingua‘s economic prosperity, transformed this remote Texas borderland into a thriving mining community in the late 19th century.

You can trace this evolution from primitive mining methods—hand-sorting cinnabar and using burro-drawn carts—to industrialized operations after Howard Perry established the Chisos Mining Company in 1903.

The mercury market exploded during World War I when European supplies dwindled and military demand surged. By 1934, the operation had generated approximately $12 million in sales.

However, prosperity proved fleeting. By 1936, recoverable ore bodies depleted, and an insurmountable groundwater influx eventually forced abandonment in 1946.

Meanwhile, Mexican migrant workers paid a devastating health price, developing mercury poisoning symptoms typically within five years of employment.

The town was strategically divided into two separate areas for Mexicans and Anglos, reflecting the social hierarchy that dominated the mining operation’s community structure.

Despite harsh conditions, the community developed amenities including a well-stocked commissary and ice plant that served residents within a 100-mile radius.

Glen Rio: A Town Divided by State Lines

If you’d ever visited Glenrio during its brief heyday, you’d have encountered a unique economic ecosystem where Texas prohibition laws created “dry” establishments on one side while New Mexico’s higher gasoline taxes influenced where travelers refueled.

These state-line dynamics initially fostered commerce as Route 66 travelers strategically patronized businesses on either side based on favorable regulations, creating a symbiotic commercial arrangement despite the political boundary.

Today, only a few buildings remain, including the iconic 1950 Texaco station with its original pumps, attracting Route 66 enthusiasts and historians exploring America’s transportation heritage.

The completion of Interstate 40 in 1973 delivered the final blow to this delicate economic balance, as traffic bypassed the town entirely, rendering both the Texas and New Mexico portions equally obsolete.

John Steinbeck’s famous novel “The Grapes of Wrath” was filmed in Glenrio in 1938, adding to the town’s historical significance along Route 66.

Border Town Economics

Positioned perfectly on the Texas-New Mexico boundary established by the Compromise of 1850, Glenrio represents a fascinating case study in border town economics, where an arbitrary political line created a uniquely divided commercial ecosystem.

You’ll find the town’s businesses strategically positioned to exploit jurisdictional challenges. Texan prohibition laws meant alcohol sales flourished on the New Mexico side, while higher gas taxes in New Mexico guaranteed service stations operated exclusively in Texas.

This border town dynamic shaped the town’s physical layout—businesses advertised themselves as either the “Last Stop in Texas” or “First Stop in New Mexico” to capture traveler interest.

The dual jurisdictions ultimately contributed to Glenrio’s vulnerability. When Interstate 40 bypassed the settlement in the 1970s, the fragile economic balance collapsed, unable to sustain itself without through-traffic. The town’s decline was swift, with its population ultimately dropping to zero residents by 2025. Before its decline, Glenrio was a thriving community that even served as a filming location for The Grapes of Wrath in 1940.

Interstate 40 Deathblow

When Interstate 40 cut its path across the Texas Panhandle in 1973, it delivered the fatal blow to Glenrio’s fragile existence, bypassing the once-vibrant Route 66 stopover by several hundred yards and effectively severing its commercial lifeline.

You’ll find that Glenrio’s history ended abruptly as I-40 redirected traffic away from this unique border settlement. By 1975, most businesses had closed, including the Ehresman family grocery that relocated to New Mexico. The Texas Longhorn Motel and State Line Cafe, which were once popular stops for travelers, now stand abandoned and heavily vandalized.

The Interstate impact was devastating—particularly following the earlier 1955 closure of the Rock Island railroad depot that had initially sustained the town.

The town that once thrived with Texaco stations, the State Line Bar and Motel, and various eateries catering to Route 66 travelers vanished almost overnight—victim to transportation progress that paradoxically destroyed what it once created. Today, visitors can explore the Glenrio Historic District that preserves the remnants of this border town’s fascinating past.

How Railroad Bypasses Created Texas Ghost Towns

Railroad bypasses fundamentally altered the landscape of Texas settlements during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, transforming once-thriving communities into abandoned relics of the Old West.

You’ll find railroad influence was paramount as companies leveraged their land grants to dictate which communities would thrive and which would perish.

Consider these critical patterns of town resilience:

Railroad decisions carved the destiny of frontier communities, determining which would prosper and which would fade into Texas history.

- Helena lost its county seat to Karnes City when railroad officials rerouted, forcing residents to physically relocate buildings.

- Toyah’s economic dependence on the Texas & Pacific Railroad ultimately led to its abandonment.

- Towns like Sherwood declined from population centers to near-empty shells after 1911 railroad bypasses.

- Communities often mortgaged themselves into financial ruin competing for railroad access, only to be discarded when lines were abandoned.

Towns that successfully diversified economically managed to survive despite the eventual abandonment of railroad lines that once sustained them.

Glenrio exemplifies this pattern as it thrived along historic Route 66 until Interstate 40 bypassed it, leading to its decline and eventual abandonment.

Unearthing the Submerged Ruins of Bluffton

Unlike traditional ghost towns abandoned to desert elements, you’ll find Bluffton’s remains beneath Lake Buchanan’s waters, intentionally flooded in 1937 when the dam was completed for electricity and flood control.

During severe droughts in 1984 and 2009, receding water levels exposed the town’s architectural footprint—foundations, cotton gin ruins, and the hotel’s storm cellar—offering rare glimpses into a once-thriving agricultural community.

Before submersion transformed Bluffton into an underwater time capsule, approximately fifty families cultivated crops and operated businesses in this Central Texas settlement established in the 1850s along the Colorado River.

Watery Grave Since 1937

Although originally projected to take four years to reach capacity, Lake Buchanan submerged the town of Bluffton within mere months of the dam’s 1937 completion, transforming the once-thriving frontier settlement into an underwater archaeological site.

This accelerated submersion of Bluffton history resulted from:

- Unexpected rainfall exceeding 20 inches

- Federal acquisition of properties at Depression-era prices

- Hasty relocation of residents to higher ground

- Exhumation of cemetery graves with one remaining unclaimed

The watery grave now preserves submerged artifacts approximately 30 feet below surface under normal conditions.

Multiple droughts, especially in 1984 and 2009, have temporarily exposed the ruins, allowing Texas Historical Commission researchers to document foundations, implements, and cultural remnants.

These preserved elements provide tangible connections to frontier life before federal intervention permanently altered this community’s trajectory.

Drought Reveals Hidden Past

When severe drought gripped Texas in 1984 and again in 2009, the receding waters of Lake Buchanan gradually disclosed what locals had long considered lost to history—the preserved remnants of Old Bluffton.

As water levels dropped dramatically—by approximately 26 feet in 2009—you could walk where a vibrant community once thrived before submersion. The drought impacts disclosed foundations of homes, businesses, and even a cemetery, offering unprecedented access to this underwater time capsule.

Archaeologists meticulously documented the town’s layout, recovering medicine bottles, blacksmith tools, and other artifacts essential for historical preservation.

Descendants of original settlers contributed family narratives, enhancing understanding of this submerged heritage. Though protected by law against removal, these temporarily exposed ruins allowed you brief glimpses into Texas frontier life before inevitably disappearing beneath rising waters once again.

Life Before The Flood

As the receding waters gradually revealed the ghostly contours of original Bluffton, archaeologists and historians began piecing together a detailed portrait of life in this once-thriving settlement before its intentional flooding.

Before the dam project claimed their town in the 1930s, Bluffton’s residents maintained robust community bonds while engaging in essential agricultural practices.

You can trace their self-sufficient existence through the remnants of:

- A central cotton gin that processed the community’s harvests for regional markets

- Fertile fields once yielding corn, cotton, and pecans that sustained approximately 50 families

- The general store that functioned as both commercial center and social gathering space

- A community cemetery where traditions and history were preserved

This hardworking settlement exemplified the independent spirit of early Texas Hill Country communities—a legacy now preserved only in scattered artifacts and oral histories.

Medicine Mound: From Commercial Hub to Cultural Museum

Named for the four sacred conical mounds revered by the Comanche people for their spiritual and healing properties, Medicine Mound emerged as a commercial center in 1908 when the Kansas City, Mexico and Orient Railway Company established a watering stop for steam engines.

The town’s Medicine Mound history reflects rapid growth—reaching 500 residents and 22 businesses by 1929—before a devastating 1932 fire destroyed most structures and all town records.

This catastrophe, allegedly set by Ella Tidmore, coupled with economic hardship, accelerated the town’s decline.

Today, you’ll find the Medicine Mound Museum housed in a refurbished 1927 general store, preserving the cultural significance of this now-ghost town.

The museum chronicles local farm and ranch life while displaying Native American artifacts—grinding stones and arrowheads—found near the spiritually significant mounds that gave this vanishing Texas community its name.

The Economic Collapse of Cotton Farming Communities

The economic foundation of countless Old West Texas towns rested precariously on the cotton industry, which experienced dramatic growth from the late 19th to early 20th centuries, producing over 3.5 million bales by 1900—a tenfold increase from 1869 levels.

This cotton economy created a fragile prosperity that ultimately collapsed under multiple pressures:

- The boll weevil invasion from Mexico devastated crops statewide, exposing the vulnerability of agricultural mono-economies.

- Tenant struggles intensified during the Great Depression as cotton prices plummeted, forcing mass migration from rural communities.

- Federal programs like the Agricultural Adjustment Act reduced acreage but failed to address systemic inequities.

- Post-WWII mechanization eliminated thousands of jobs, concentrating wealth in fewer hands while rural towns withered.

When you visit these abandoned communities today, you’re witnessing the aftermath of this economic upheaval.

Cemeteries and Graves: Silent Storytellers of Texas’s Frontier Past

Cemeteries scattered across abandoned Texas Old West towns serve as poignant archaeological sites where visitors can read the unwritten histories of frontier communities long after their buildings have crumbled and populations dispersed.

You’ll find folk art traditions manifested in hand-decorated grottos at Terlingua Cemetery and mysterious seashell-adorned graves in Comfort.

Cemetery preservation efforts vary dramatically—some sites like the notorious John Wesley Hardin’s prison-like grave receive regular maintenance, while others slowly return to nature.

These burial grounds often remain the sole physical evidence of vanished communities, making them vital cultural anchors.

When you visit these sacred spaces, you’re encountering both personal and collective narratives—tales of outlaws, settlers, and local heroes—all expressed through distinctive burial practices that reflect the multicultural tapestry of Texas’s frontier societies.

Architectural Remnants: What Survives When Towns Die

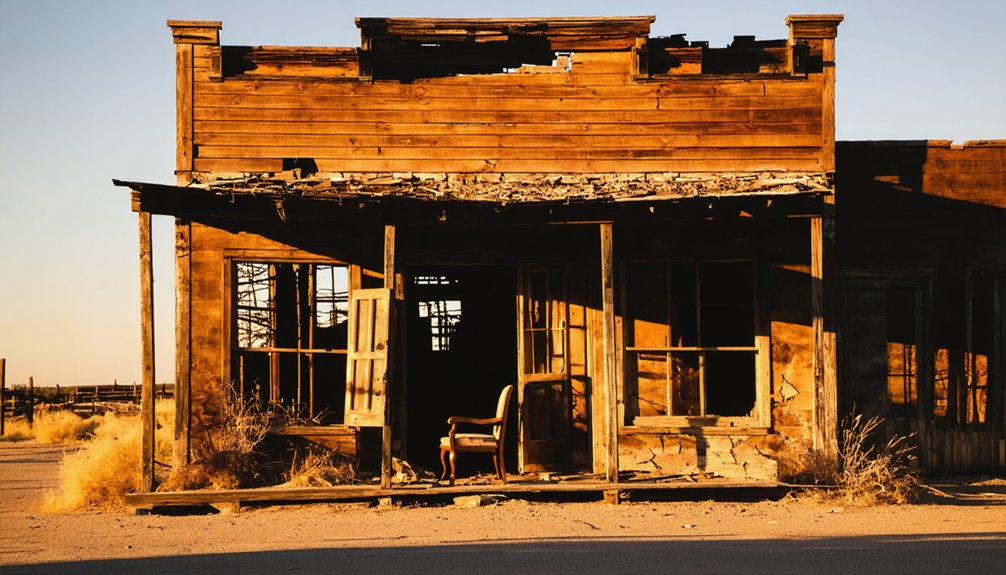

Crumbling masonry, half-collapsed frameworks, and weathered foundations tell the architectural stories of Texas ghost towns long after their inhabitants have departed.

These remnants, each with distinct historical significance, reveal the hierarchy of permanence in frontier settlements.

Time reveals what settlers valued most: stone churches remain while wooden homes surrender to prairie winds.

When exploring these abandoned landscapes, you’ll discover:

- Religious structures endure longest – churches stand sentinel while towns flood beneath Lake Texoma

- Commercial buildings like mills and stores persist with their architectural styles revealing economic priorities

- Public infrastructure (courthouses, jails, post offices) remains as evidence of civic ambition

- Residential foundations tell intimate stories through their scattered patterns

The stone walls of Aldridge’s sawmill and Belle Plain College’s weathered ruins stand as defiant monuments against time’s erosion, while cemetery markers continue their silent testimony to lives once lived in these forgotten spaces.

From Boomtown to Bust: Mining and Resource Depletion

While architectural remains speak to the physical past of Texas ghost towns, mineral wealth once buried beneath the soil tells an equally compelling story of ambition and impermanence.

In Shafter, Terlingua, and Thurber, you’ll find the narrative of Texas boom-and-bust cycles perfectly preserved. These towns flourished through distinct mining methods—silver extraction in Shafter, mercury mining in Terlingua, and coal production in Thurber—each supporting thousands of residents during their prime years.

The economic impact was transformative but fleeting; Terlingua alone produced 40% of America’s wartime quicksilver, while Thurber’s coal powered the state’s industrial revolution.

Yet market fluctuations, resource depletion, and technological shifts inevitably triggered their downfall. Silver prices collapsed, mercury demand evaporated, and oil replaced coal—leaving behind skeletal towns where thousands once sought their fortunes.

Visiting Texas Ghost Towns: Access and Preservation Challenges

Despite their historical significance, accessing and preserving Texas ghost towns presents a complex array of challenges for both visitors and conservationists alike.

Ghost town accessibility remains problematic due to remote locations, private land restrictions, and deteriorating rural infrastructure that requires determination to navigate.

Preservation initiatives operate through four primary channels:

- County historical commissions that survey sites and maintain historical markers

- Volunteer boards managing cemetery and building maintenance

- Local museums and historical societies hosting fundraising events

- Grant-funded partnerships with academic institutions

Your visit to these historical remnants directly supports conservation efforts, though you’ll need to balance your desire for exploration with respect for both private property boundaries and the fragile nature of these weathered structures.

Community-led events offer authentic engagement while generating essential revenue for ongoing preservation work.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are Ghost Towns Legally Protected as Historical Sites in Texas?

Some Texas ghost towns receive historical preservation through landmark designations, while others remain unprotected. You’ll find legal regulations vary considerably, leaving many vulnerable to development despite their cultural significance.

Do Any Ghost Towns Still Have Permanent Residents Today?

While you might think ghost towns are completely deserted, several Texas settlements maintain modern inhabitants who support ghost town tourism through creative enterprises like Terlingua’s art scene and Helena’s community-run museums and historical societies.

What Paranormal Activity Is Reported in Texas Ghost Towns?

You’ll encounter EVP recordings, apparitions in Victorian homes, ghostly cowboys, and inexplicable light phenomena in Texas ghost towns. These haunted locations report physical disturbances, shadow figures, and spectral voices linked to violent histories.

Which Ghost Towns Are Featured in Popular Films or TV Shows?

Terlingua, a treasure trove of cinematic history, tops the list as you’ll discover its dusty streets in “Gambler V” and “Streets of Laredo”—both capitalizing on its authentic film locations and haunting aesthetic.

Can Metal Detectors Be Used at Abandoned Texas Town Sites?

You generally can’t legally use metal detectors at abandoned Texas towns without proper permits. Metal detecting laws restrict public land searches, while treasure hunting ethics demand respecting historical preservation and obtaining landowner permissions first.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zd8-gKw-5Hc

- https://www.hipcamp.com/journal/camping/texas-ghost-towns/

- https://livefromthesouthside.com/10-texas-ghost-towns-to-visit/

- https://tpwmagazine.com/archive/2018/jan/wanderlist_ghosttowns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6u47HvHWZXM

- https://mix931fm.com/texas-ghost-towns-history/

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TOWNS/Texas_ghost_towns.htm

- https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g28964-Activities-c47-t14-Texas.html

- https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/TXPWD/bulletins/1dcdee4

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/tx-terlingua/