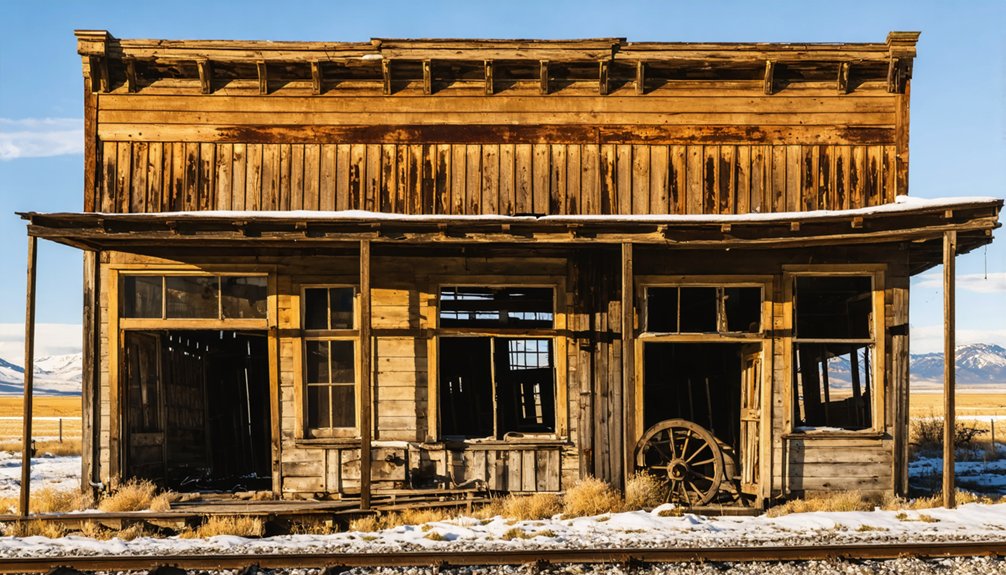

America’s Victorian ghost towns offer you haunting glimpses into the boom-and-bust mining era. From Bodie’s gold rush buildings preserved in “arrested decay” to Virginia City’s ornate opera house, these abandoned settlements showcase the fragility of frontier dreams. You’ll find architectural treasures in St. Elmo, vigilante justice remnants in Bannack, and engineering marvels in Silverton. Each silent street and weathered building tells a compelling story of ambition, prosperity, and ultimate abandonment.

Key Takeaways

- Bodie, California features 110 buildings in “arrested decay” and generated over $100 million in gold wealth during its prime.

- Virginia City, Nevada preserves Victorian architecture including Storey County Courthouse and Piper’s Opera House from its silver boom days.

- St. Elmo, Colorado sits at 9,960 feet elevation with perfectly preserved structures from its mining heyday.

- Rhyolite, Nevada grew from two tents to Nevada’s fourth-largest city by 1906 before rapidly declining.

- Silverton, Colorado showcases Victorian buildings and steam locomotives that reflect its rich silver mining heritage.

Bodie, California: Where the Wild West Stands Frozen in Time

While gold rushes transformed the American West in the 19th century, few ghost towns capture the essence of this era quite like Bodie, California. Named after prospector William S. Bodey—though misspelled—this once-thriving boomtown emerged from a modest camp into a raucous settlement of 10,000 souls following an 1876 gold vein discovery.

You’ll find Bodie architecture preserved in “arrested decay,” with about 110 buildings frozen as they were abandoned—from schoolhouses to saloons, all untouched since the town’s decline. The town’s reputation for lawlessness was earned with its sixty saloons operating by 1880. The town generated an impressive over $100 million in gold wealth for Mono County during its prime.

The site’s remote Sierra Nevada location adds to its eerie charm, while Bodie folklore includes tales of a curse befalling anyone who removes artifacts. The Boothill Graveyard and John S. Cain House feature prominently in ghost stories that draw 200,000 visitors annually to experience this authentic slice of lawless frontier life.

Cahaba, Alabama: From State Capital to Silent Ruins

As you explore the abandoned streets of Cahaba, you’ll witness the remains of Alabama’s first state capital, established in 1820 at the confluence of the Cahaba and Alabama Rivers, yet repeatedly devastated by floods that ultimately contributed to its downfall.

The town experienced a remarkable transformation after the Civil War when formerly enslaved people established a vibrant freedmen’s community among the decaying mansions and commercial buildings.

These contrasting historical layers—from political center to plantation economy to post-emancipation refuge—are preserved in the archaeological remnants that dot the landscape of today’s Old Cahawba Archaeological Park. William Wyatt Bibb, who served as the first governor of Alabama from 1819-1820, played a significant role in Cahaba’s initial development as the state capital before the seat of government was relocated.

Visitors today can also witness the decaying brick capitol building, constructed during the town’s brief period of prosperity before being abandoned to the elements and recurring floodwaters.

Alabama’s Flood-Prone Capital

When Alabama achieved statehood in 1818, the fertile land at the confluence of the Cahaba and Alabama Rivers promised an ideal location for a capital city.

Governor William Bibb’s vision was quickly realized as Cahaba emerged with its brick capitol and grid-patterned streets.

Yet nature had other plans.

The capital’s strategic riverside position proved its downfall. Without modern flood management systems, Cahaba suffered catastrophic inundations that repeatedly:

- Submerged government buildings for weeks

- Damaged critical infrastructure

- Created health hazards in the swampy environment

- Forced emergency evacuations

- Destroyed private property and commercial establishments

The most devastating flood came in 1865, completely submerging the town and transforming once-thriving streets into marshlands.

These concerns ultimately led to the relocation of Alabama’s capital to Tuscaloosa on February 1, 1826.

Freedmen Community Remnants

The devastating floods that drove Alabama’s government from Cahaba marked only the beginning of the town’s remarkable transformations.

After the Civil War, the abandoned streets found new purpose as freedmen, mostly former slaves from nearby plantations, created a vibrant community amid the ruins.

You can still walk the preserved street grid where freedmen established a political revival that earned Cahaba the nickname “Mecca of the Radical Republican Party.”

The old courthouse, now vanished, once hosted meetings where African American residents organized and eventually sent representatives to state and national offices.

Jeremiah Haralson’s rise from slavery to Congress exemplifies this freedmen legacy.

Local folklore persists about the area, with numerous ghost sightings reported near Celia Pegasus’s grave where visitors still leave flowers today.

By 1900, Cahaba had become a ghost town with only about 300 residents remaining, primarily comprised of former slaves who had stayed in the area despite its decline.

Kennecott, Alaska: The Copper Kingdom of the North

Nestled within the rugged Alaskan wilderness, Kennecott stands as America’s most remarkable copper mining ghost town, born from one of history’s most significant mineral discoveries.

When you visit this preserved Victorian-era settlement within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, you’re walking through what was once the world’s richest copper operation, producing ore worth $3 billion in today’s currency.

- The massive 196-mile railway built before the first copper shipment demonstrates the extraordinary investment ($730 million in modern terms).

- From 1911-1938, the operation extracted 4.6 million tons of high-grade ore.

- The imposing mill building—Alaska’s largest structure at the time—dominates the landscape.

- Victorian architecture of the company town remains largely intact.

After the final train departed in November 1938, nature reclaimed this copper kingdom. The discovery of copper in the area was first noted by Russian explorers as early as the 1700s, though significant development would wait until the early 20th century. The abrupt abandonment left many personal belongings behind, including dinner tables that remained set as if waiting for miners to return from their shifts.

St. Elmo, Colorado: A Mining Dream Preserved in the Rockies

High in the Colorado Rockies at an elevation of 9,960 feet, St. Elmo stands as one of America’s most perfectly preserved ghost towns. Originally named Forest City in 1880, postal confusion prompted its renaming after a popular Victorian novel.

When you visit, you’re walking through living history—where a mining boom once supported 2,000 residents, five hotels, and countless saloons.

The town’s prosperity hinged on the Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad, which transported ore and supplies until 1922.

Though devastated by an 1890 fire and declining mining yields, St. Elmo’s mining heritage remains remarkably intact. Unlike many abandoned settlements, this National Register Historic District retains numerous original structures, offering you an authentic glimpse into America’s frontier past without the sanitized veneer of commercial restoration.

Exploring forgotten towns in the United States can uncover hidden gems filled with rich history and unique stories. Each abandoned site holds the echoes of a bygone era, inviting intrepid travelers to immerse themselves in the past. The allure of these forgotten towns beckons those seeking adventure beyond the typical tourist routes.

Garnet, Montana: The Golden Ghost of the Continental Divide

Founded in 1895 at the head of First Chance Gulch, Garnet emerged as Montana’s quintessential boom-and-bust mining settlement. Originally named Mitchell, the town was renamed for the ruby-colored stones found in the area.

From humble Mitchell to iconic Garnet, Montana’s mining history gleams like the ruby stones that gave it name.

As you explore this mountain sanctuary at 6,000 feet elevation, you’ll encounter a ghostly atmosphere amid remarkably intact Victorian structures.

When gold fever struck, Garnet’s population swelled to nearly 1,000 residents by 1898, creating a vibrant community where mining legacy remains visible today:

- Thirteen saloons once flowed with liquor, while families maintained a surprisingly stable community

- A devastating 1912 fire accelerated the town’s decline

- Roosevelt’s 1934 gold price increase briefly revived the settlement

- BLM now preserves this haunting slice of Western history

- Original furnishings remain, enhancing the town’s authentic Victorian character

Virginia City, Nevada: Silver Baron Legacy on the Comstock Lode

When you stroll Virginia City’s C Street, you’ll encounter dozens of original Victorian buildings, from the ornate Storey County Courthouse to the iconic Piper’s Opera House, all testifying to the extraordinary wealth generated by the Comstock Lode.

The town’s entertainment culture flourished during its silver heyday with over 100 saloons and numerous theaters where Mark Twain honed his craft as a writer for the Territorial Enterprise newspaper.

Beyond the surface attractions, you can explore remarkable engineering achievements that made mining possible, including the revolutionary square-set timbering system that prevented cave-ins and the intricate Sutro Tunnel that drained water from the mines.

Historic Buildings Standing Tall

Virginia City stands as a remarkable tribute to America’s silver mining legacy, with its skyline still defined by the magnificent structures built during the Comstock Lode’s heyday.

This National Historic Landmark District exemplifies Victorian-era historic preservation at its finest, showcasing diverse architectural styles that tell the story of America’s largest silver strike.

As you wander the wooden sidewalks, you’ll discover:

- The Fourth Ward School – America’s last standing multi-story wooden schoolhouse

- Storey County Courthouse – Nevada’s oldest continuously operating courthouse

- Mansions of the “Bonanza Kings” featuring Second Empire designs

- The Territorial Enterprise building where Mark Twain once worked

- Miner’s Union Hall preserving the town’s industrial heritage

These structures aren’t mere relics; they’re physical embodiments of the extraordinary wealth generated by the $400 million silver boom.

Wild West Entertainment Culture

As the silver from the Comstock Lode flowed abundantly through Virginia City’s coffers in the 1860s and 1870s, a remarkably vibrant entertainment culture blossomed in this mountain boomtown.

You’d find saloons and gambling halls packed with miners fresh from their shifts, keen to spend their newfound wealth.

The Territorial Enterprise, where Mark Twain honed his craft, chronicled the parade of vaudeville legends gracing local stages.

Buffalo Bill himself performed here, leaving an indelible mark on the town’s cultural identity.

When you visit today, you might sense ghostly performances echoing through historic theaters where minstrel shows and variety acts once entertained the masses.

These entertainment venues served as the social heartbeat of Virginia City, drawing visitors from across America and cementing the settlement’s reputation as the quintessential Wild West destination.

Mining Innovations Preserved

Beyond the raucous saloons and vaudeville shows, Virginia City’s true foundation lay in the revolutionary mining technologies that forever changed American industry.

When you explore this preserved industrial heritage, you’ll witness firsthand the ingenuity that extracted millions in silver from the famous Comstock Lode.

- Square-set timbering techniques, pioneered by Philip Deidesheimer, allowed miners to safely extract ore from vast underground chambers.

- The Sutro Tunnel, a remarkable engineering feat completed in 1878, drained scalding water from deep mines.

- Washoe pan amalgamation mills revolutionized ore processing efficiency.

- Original Cornish pumps and air compression drills showcase technological innovation.

- The Nevada Mill (1887) stands preserved as a monument to industrial-scale mining operations.

Virginia City’s National Historic Landmark status guarantees these mining technology achievements remain accessible, offering you glimpses into the revolutionary practices that spread worldwide.

Thurmond, West Virginia: The Railroad Boomtown Time Forgot

Nestled within the rugged terrain of the New River Gorge, Thurmond, West Virginia stands as one of America’s most perfectly preserved railroad boomtowns, offering visitors a haunting glimpse into the nation’s industrial past. Founded in 1873 by Captain William D. Thurmond, this strategic settlement quickly became the heartbeat of coal transportation in the region.

You’ll be walking through a town that once outperformed major cities in railroad revenue, generating nearly $5 million annually for the C&O Railway by 1910.

Despite being accessible only by rail until 1921, Thurmond thrived with hotels, banks, and its own electric plant. As diesel locomotives replaced steam and highways diminished railroad dependency, this once-bustling hub gradually emptied.

Today, with fewer than five residents, Thurmond’s preserved structures stand as silent sentinels of America’s industrial heritage.

Bannack, Montana: Where Vigilante Justice Shaped the Frontier

When you visit Bannack today, you’ll stand in the shadow of one of the West’s most notorious lawmen-turned-outlaws, Sheriff Henry Plummer, whose criminal enterprises allegedly netted thousands in stolen gold before vigilante justice caught up with him.

The gallows where Plummer and his “Innocents” gang met their fate in 1864 serves as a stark reminder of frontier justice administered without formal trials or legal proceedings.

Your walk through the town’s preserved buildings traces a community that transformed from lawless gold camp to the epitome of vigilante rule, where the hangman’s noose at Hangman’s Gulch became both solution and symbol of the desperate measures citizens took to establish order.

Sheriff’s Gold-Stained Past

Among the many intriguing characters who shaped America’s frontier history, few remain as controversial as Henry Plummer, the elected sheriff of Bannack who allegedly led a double life as the mastermind behind the notorious “Innocents” gang.

When you visit Bannack today, you’re walking through the remnants of a town where sheriff corruption and vigilante trials defined daily life.

Plummer’s story exemplifies the lawless reality of 1860s Montana:

- His gang allegedly murdered around 100 travelers in 1863 alone

- Plummer used his position to leak gold shipment routes to accomplices

- The gold’s exceptional 99-99.5% purity made it an irresistible target

- Vigilantes hanged him alongside his deputies in 1864

- His final request for a “good drop” haunts the town’s violent legacy

Hangman’s Gulch Legacy

Plummer’s fate ultimately unfolded in Bannack’s most notorious site—Hangman’s Gulch, a small ravine on the town’s north side that permanently altered Montana’s frontier history.

As you walk the path to the reconstructed gallows, you’re retracing the final steps of Plummer and his deputies, executed by vigilantes on January 10, 1864, in sub-zero temperatures.

The Montana Vigilantes, operating outside formal law, claimed these frontier executions were necessary justice against Plummer’s alleged road agent gang.

Their skull-and-crossbones symbol with “3777” became infamous as they hanged over twenty men that winter.

Today, standing in this preserved gulch within Bannack State Park, you’ll feel the tension between order and lawlessness that defined the American frontier.

This haunting site remains both educational landmark and sobering reminder of vigilante justice’s complicated legacy.

Rhyolite, Nevada: Rise and Fall of a Desert Metropolis

In the desolate reaches of the Amargosa Desert, just beyond Death Valley National Park’s boundaries, Rhyolite stands as a tribute to America’s quintessential boom-and-bust mining cycle.

When you explore Rhyolite’s history, you’ll discover a town that exploded from two tents into Nevada’s fourth-largest city within just two years after gold’s 1904 discovery.

- Three-story John S. Cook Bank building remains as Nevada’s most photographed ghost town relic

- Population swelled to 5,000 by 1906, then plummeted to 675 by 1910

- Mining challenges became insurmountable by 1909 as ore quality diminished

- Last residents departed by 1916 when electricity was shut off

- Bottle House, constructed of 50,000 bottles, still stands as evidence of frontier ingenuity

The ruins, now preserved by the Bureau of Land Management, offer you a haunting glimpse into ambition’s fragility.

Silverton, Colorado: The Alpine Mining Marvel That Survived

Unlike Rhyolite’s swift demise, Silverton represents the rare ghost town that refused to surrender completely to time’s march. Founded in 1874 following the Brunot Treaty that opened Ute lands to settlers, this alpine mining hub quickly flourished with rich silver veins that attracted thousands.

You’ll find Silverton’s mining legacy etched into its Victorian architecture and engineering marvels like the Chattanooga Loop railroad.

While neighboring camps like Animas Forks succumbed to abandonment after the Gold Prince Mill closed in 1910, Silverton weathered the Panic of 1893 and post-WWI economic shifts.

Today, Silverton heritage remains tangible in its preserved buildings and steam locomotives. This resilient town transformed its near-ghost status into cultural capital, inviting you to experience a genuine slice of America’s resource-driven westward expansion.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Overnight Accommodations Within Any of These Ghost Towns?

You’ll find limited ghost town accommodations, with Virginia City offering authentic historical lodging options while most others require you to stay in nearby towns due to preservation restrictions.

How Do Winter Weather Conditions Affect Accessibility to These Locations?

Winter severely limits access as remote roads lack snow removal and experience frequent closures. You’ll face impassable trails, structural hazards, and increased safety risks in these isolated locations without services.

What Paranormal Investigation Equipment Is Allowed at These Historic Sites?

90% of ghost towns permit basic paranormal tools like EMF meters and digital recorders. You’ll need to follow specific investigation guidelines regarding tripods, surface-contact equipment, and battery-powered devices at these historically sensitive locations.

Do Any Towns Have Restrictions on Photography or Artifact Collection?

Yes, you’ll find strict photography regulations requiring permits at most sites, while artifact preservation laws prohibit collection entirely—violators face hefty fines up to $10,000 and potential imprisonment for removing historical items.

Which Ghost Towns Are Wheelchair Accessible or ADA Compliant?

Necessity is the mother of invention, and you’ll find wheelchair accessibility in Bodie’s high-flotation chairs, Goldfield’s paved walkways, Tombstone’s ADA-compliant streets, and Ashcroft’s main thoroughfare, though side paths remain challenging for mobility devices.

References

- https://devblog.batchgeo.com/ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Ghost_towns

- https://www.loveexploring.com/gallerylist/131658/abandoned-in-the-usa-92-places-left-to-rot

- https://www.tastingtable.com/694562/scariest-ghost-towns-country/

- https://www.wideopencountry.com/the-10-eeriest-ghost-towns-in-america/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SUsnGxOpcss

- https://www.christywanders.com/2024/08/top-ghost-towns-for-history-buffs.html

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a7zS5kapSVw

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_ghost_towns_in_the_United_States