You’ll find Huron’s haunting ruins in Pennsylvania’s coal country, where a once-bustling mining town thrived in the early 1900s with over 2,700 residents. The community centered around traditional room-and-pillar mining operations, employing thousands until the mid-20th century decline. Today, landmarks like the Stone Church and Odd Fellows Cemetery stand as silent witnesses to Huron’s industrial past, while toxic groundwater and underground fires tell a cautionary tale of environmental neglect.

Key Takeaways

- Huron became a ghost town following the decline of coal mining operations and the devastating environmental impacts of toxic groundwater contamination.

- The town’s population peaked at 2,700 residents during mining prosperity but emptied after the 1959 Knox Mine Disaster.

- Environmental hazards, including underground coal fires and contaminated wells, forced the permanent evacuation of residents from the area.

- The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church remains one of the few standing structures amid Huron’s abandoned streets.

- Annual gatherings of former residents and preservation efforts through documentaries and exhibitions maintain Huron’s historical legacy.

The Early Settlement Years

While Native American tribes had long inhabited the Pennsylvania wilderness, the area that would become Huron saw its first European settlement attempts in the early 1830s.

Prior to European arrival, the region was home to the Lenape tribes who had developed sophisticated agricultural practices in the area.

You’d have found a rugged landscape of dense forests where Jonathan Faust built the Bull’s Head tavern illegally along the Reading Road, marking the first permanent structure. The Reading Road construction had begun around 1810, creating the first major transportation route through the region.

Early settlers faced formidable settlement challenges, from deep winter snows to nearly impenetrable woods.

Mining Operations and Economic Growth

As Pennsylvania’s coal industry boomed in the late 19th century, Huron emerged as a significant mining center through operations by industry giants like the Cambria Iron Company and Pennsylvania Coal & Coke Company.

The region’s mining history traces back to when white settlers arrived, with early coal extraction beginning in the Conemaugh Valley during the 1760s. These early mines followed the pattern seen across the state, where drift mines extracted coal from exposed seams and transported it by water.

You’d find miners using traditional room-and-pillar mining methods throughout the region’s bituminous coalfields, a practice that defined western Pennsylvania’s coal extraction for generations.

The economic contributions of Huron’s mines were substantial. By 1912, you could count roughly 3,000 workers employed in the area’s mines, with Pennsylvania Coal & Coke operating hundreds of coal ovens and producing millions of tons of coal.

Huron’s mines employed thousands and produced massive coal outputs, powering Pennsylvania’s industrial might in the early 1900s.

The industry’s influence stretched beyond mere employment, spurring the development of critical infrastructure like railroads and processing facilities that transformed the region’s landscape and strengthened its economic foundation.

Daily Life in Peak Years

During Huron’s prosperous peak years, you’d find a vibrant community of roughly 2,700 residents going about their daily routines in this bustling coal town.

Life revolved around the mines, where men worked grueling shifts while women managed households and local commerce. The town’s early economy thrived thanks to the Locust Mountain Company establishing crucial mining operations. Similar to other towns in Western Pennsylvania, the community relied heavily on coking facilities to process coal from nearby mines. You’d see children heading to the town’s schools, and families gathering at one of several churches that served as both spiritual centers and social hubs.

The town’s hotels, theaters, and saloons provided much-needed entertainment after long workdays. Local stores stocked essential goods, while the post office and bank kept the community connected and commerce flowing.

Despite the harsh realities of mining life – health hazards, limited amenities, and economic uncertainties – strong community gatherings and multi-generational households created resilient bonds that defined daily existence.

The Decline of Coal Industry

Once the thriving lifeblood of Huron’s economy, the coal industry’s decline began its steady march in the mid-20th century when deep underground deposits became increasingly costly to extract.

The rich coal mining history that had sustained generations of local families faced mounting challenges as cheaper coal from other regions flooded the market. The distressed coal towns experienced devastating unemployment rates and population loss as mining operations shuttered. The region’s prized anthracite reserves remained largely untapped as economic factors made extraction unfeasible.

You’d have seen the dramatic shift when Marcellus Shale natural gas emerged, delivering the final blow to Huron’s already struggling mines.

- The 1959 Knox Mine Disaster marked a turning point, flooding multiple operations and forcing numerous company closures.

- Premium-wage mining jobs vanished, leaving families searching for economic alternatives.

- Local leaders scrambled to implement economic revitalization strategies, but many businesses couldn’t survive the change.

Notable Buildings and Landmarks

You’ll find Huron’s historic railroad station ruins standing as weathered stone foundations near the old tracks, marking where countless coal trains once rumbled through this bustling town.

The town’s church structures, particularly the iconic Stone Church, remain as evidence of the community’s spiritual heritage and occasionally still serve local gatherings. Like the Assumption Church in Centralia, these sacred buildings have withstood the test of time.

Walking down what was once a thriving Main Street business district, you can trace the concrete and brick remnants of storefronts where merchants served the town’s mining families. Like many Pennsylvania ghost towns affected by underground mine fires, the community was eventually abandoned as the ground became unstable.

Historic Railroad Station Ruins

The crumbling remnants of Huron’s historic railroad station stand as silent witnesses to Pennsylvania’s golden age of rail transport.

You’ll find Victorian-era railroad architecture in the weathered brick walls and stone foundations, where passengers once bustled through Queen Anne-styled waiting rooms. The station’s ruins tell a story of transportation history, from its heyday serving the Pennsylvania Railroad network to its eventual decline after World War II.

- Terra cotta trim and brownstone accents still peek through the overgrowth, hinting at the station’s former grandeur

- Foundation walls and platform fragments outline where freight houses once handled local agricultural shipments

- Rusted hardware and concrete supports mark the ghost town’s essential connection to larger rail networks

Town Church Structures

Standing atop a small hill in Huron’s abandoned landscape, Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church remains a symbol of immigrant faith and architectural resilience.

Built in 1911, this Gothic-inspired structure features white walls and distinctive light blue spires that pierce the desolate skyline. You’ll find it’s the sole surviving church building, constructed on solid bedrock that protected it from the devastating underground fires that consumed other local structures.

The church architecture reflects the modest yet durable designs favored by early 20th-century Eastern European settlers. While most buildings succumbed to demolition, this representation of community resilience continues hosting regular services.

Since 2015, it’s served as an official pilgrimage site, drawing visitors who marvel at its endurance amid the ghost town’s quiet streets.

Main Street Business District

Brick facades and weathered storefronts line what remains of Huron’s once-bustling Main Street business district, where decades of underground fires have taken their toll on the commercial heart of this mining town.

Any hopes of main street revitalization have long faded as structural instability forces the demolition of original buildings. The architectural heritage lives on through surviving elements like brick buttresses supporting townhouse walls and remnants of mixed-use structures that once housed local shops and residences.

- Railroad Avenue’s intersection with Main Street reveals the town’s mining transport roots

- Former small businesses including grocery stores, a barber shop, and general merchandise outlets shaped the economic corridor

- Weathered foundations and cracked sidewalks peek through overgrowth, while boarded windows tell tales of abandonment

Natural Disasters and Environmental Impact

You’ll find detailed county records from 1983 showing that toxic groundwater seepage affected nearly 80% of Huron’s local wells, forcing residents to rely on expensive water shipments from neighboring townships.

The contaminated aquifer devastated the region’s deer population, with Pennsylvania Game Commission surveys indicating a 65% decline in whitetail numbers between 1982-1985.

Following extensive environmental studies in 1986, state officials documented the permanent displacement of 12 native species, including the northern flying squirrel and eastern box turtle, from their traditional habitats within Huron’s township borders.

Toxic Groundwater Effects

Three major environmental hazards plagued Huron’s groundwater system over the decades: underground coal fires, toxic gas emissions, and hazardous waste contamination.

The town’s groundwater became increasingly dangerous as Max Environmental’s waste disposal operations introduced toxic chemicals that seeped into the local water table. You’d find evidence of this pollution in the foaming creeks and the strong chemical odors that permeated the area.

- Treated wastewater discharged into local waterways showed visible signs of contamination

- Toxic exposure from contaminated groundwater led to chronic health issues among residents

- Groundwater pollution persisted for over 40 years despite community demands for cleanup

County records show that regulatory inspections documented numerous violations, yet the contamination continued unchecked.

The toxic groundwater ultimately contributed to Huron’s transformation from a thriving community into an abandoned ghost town.

Local Wildlife Displacement

Multiple underground mine fires in 1962 triggered a catastrophic chain of wildlife displacement throughout Huron’s forested regions.

You’d have witnessed native species fleeing en masse as toxic gases seeped through ground fissures, forcing widespread wildlife migration away from their ancestral territories. County records documented the disappearance of small mammals, amphibians, and ground-nesting birds from contaminated zones.

The fire’s destructive reach caused severe habitat fragmentation, with surface subsidence creating treacherous barriers for surviving animals.

Local naturalists observed how displaced creatures struggled to establish new territories in surrounding areas, disrupting existing predator-prey relationships. The loss of microhabitats and vegetation cover left remaining wildlife vulnerable to predation.

Even today, the continuous release of pollutants prevents species from reclaiming their former grounds.

The Last Residents

A handful of steadfast residents remained in Huron during its final years, their numbers dwindling from 1,200 in the early 20th century to just five souls by 2020.

These last residents lived under “life estate” agreements, allowing them to stay in their homes until death while the ghost town slowly crumbled around them. Despite the dangers of toxic gases and ground instability, they chose independence over relocation.

- Strong emotional bonds to family heritage and lifelong roots drove their decision to stay

- Daily life meant maneuvering around visible fire damage, fissures, and smoke vents around their properties

- They maintained a tight-knit community despite isolation, supporting each other as local landmarks vanished

Their determination to preserve their way of life, even as the government declared eminent domain, spoke to an unshakeable spirit of freedom.

What Remains Today

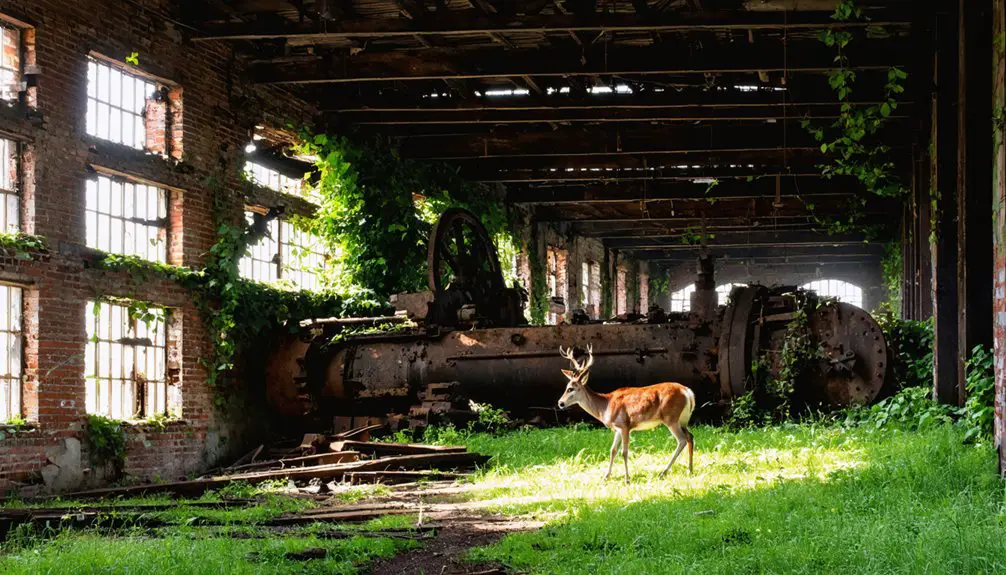

If you walk through Huron’s deserted streets today, you’ll find only a handful of original structures still standing amid the encroaching forest, while most building foundations have eroded into barely visible outlines.

The town’s transportation grid remains partially intact, with old wagon trails and former mining paths now serving as stark reminders of the once-bustling community.

Nature has steadily reclaimed large portions of Huron, transforming former residential blocks into dense woodland, though you can still trace the settlement’s original layout through scattered stone walls and cellar holes.

Physical Structures Standing

Remnants of Huron’s bygone era stand as silent witnesses to its industrial past.

You’ll find a large building with well-preserved walls and distinctive a-frame supports, showcasing early 20th-century architectural features in its milled lumber and brickwork. While nature’s reclaimed much of the town, several abandoned buildings persist, including a solitary house and a structure with garage bays, though they’re now adorned with graffiti and showing signs of decay.

- A substantial main building with intact brick walls and heavy timber framing

- Scattered auxiliary structures, including remnants of a chicken coop and farm outbuildings

- Concrete foundations hidden beneath dense woodland growth, marking where other structures once stood

The remaining structures, though weathered by time, offer glimpses into Huron’s industrial heritage through their surviving metal fixtures, pipework, and period construction methods.

Transportation Routes Visible

Transportation networks that once served Huron tell a complex story of industrial decline.

You’ll find traces of the town’s transportation history in the overgrown remnants of the Lehigh Valley Railroad tracks along Railroad Street, where two sets of tracks once carried anthracite coal to distant markets. The Mine Run Railroad, built in 1854, left faint depressions in the landscape where it connected to various mining operations.

Road reclamation efforts have largely obscured the original pathways, though you can still spot segments of the historic Reading Road beneath years of natural regrowth.

The abandoned rail sidings and switches near former loading zones offer silent testimony to Huron’s bustling past, while old mineral haul roads appear as ghostly linear clearings through the recovering terrain.

Natural Reclamation Areas

Today’s visitors to Huron encounter a haunting landscape where nature steadily reclaims the scarred terrain. The resilient forces of natural reclamation work slowly but persistently, with patches of new forest growth emerging between remnants of the town’s foundations.

You’ll witness ecological resilience in action as vegetation gradually colonizes abandoned structures and broken pavement.

- Lush forests now border the town’s perimeter, demonstrating nature’s determination to heal the disturbed land.

- Small patches of new-growth forest have taken root within the town boundaries, though progress remains patchy.

- Mosses and grasses have begun colonizing old foundations and crumbling structures, creating a stark representation to time’s passage.

Despite nature’s steady advance, some areas remain resistant to regrowth due to ongoing underground disturbances, creating a patchwork of recovery across the former settlement.

Historical Preservation Efforts

While many ghost towns slowly fade into obscurity, Huron’s preservation efforts began formally in 1992 when Pennsylvania seized most of the town’s property through eminent domain.

Through community engagement and historical narratives, you’ll find documentaries, books, and exhibitions that keep the town’s memory alive. The few remaining structures, including the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church and Odd Fellows Cemetery, stand as silent witnesses to Huron’s past.

You’ll notice nature’s steady reclamation of former residential areas, while Route 61’s closure preserves both public safety and the site’s historical integrity.

Legal frameworks now protect the land from redevelopment, ensuring future generations can learn from this cautionary tale of industrial negligence, while carefully managed access allows for controlled remembrance of what once was.

Legacy and Cultural Significance

Beyond its physical remains, Huron’s enduring impact resonates deeply through cultural memory and artistic expression.

You’ll find that this former mining settlement embodies the complex relationship between industrial heritage and community bonds. Like many coal towns of its era, Huron’s cultural heritage lives on through the stories passed down by former residents and their descendants, who maintain a vibrant community memory despite physical displacement.

Former mining towns like Huron live on through generational storytelling, keeping community ties strong despite their physical absence.

- Former residents gather annually to share photographs, artifacts, and personal accounts, preserving the town’s legacy for future generations.

- Local museums showcase Huron’s contributions to Pennsylvania’s anthracite mining history through exhibitions and oral histories.

- Artists and documentarians continue drawing inspiration from Huron’s abandoned landscape, transforming its industrial decay into powerful statements about environmental stewardship and community resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Documented Paranormal Activities Reported in Huron’s Abandoned Structures?

You’ll find documented ghostly encounters through EVP sessions in abandoned houses, with investigators recording spirit communications and haunted locations marked by unexplained voices, particularly in duplex homes containing family artifacts.

What Happened to the Town’s Official Documents and Records After Abandonment?

You’ll find many of the town archives were likely transferred to county records, though some are missing records altogether, lost to demolition and abandonment when state authorities seized properties.

Did Any Famous People or Celebrities Ever Visit Huron?

You won’t find any documented celebrity sightings or historical visits by famous figures. County records and official documents show no evidence of well-known personalities ever stopping by this intriguing destination.

Were There Any Unsolved Crimes or Mysteries Associated With Huron?

You won’t find any documented unsolved mysteries or credible ghost sightings in county records. Despite its ghost town status, the area’s history shows no evidence of unexplained criminal cases or paranormal phenomena.

Did the Government Attempt to Relocate Huron’s Residents to a Specific Location?

No, you weren’t forced into a single location. The government relocation program gave Huron residents cash settlements for their properties, letting you choose where to move and rebuild your life independently.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qj5LjacccJ0

- https://pabucketlist.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-centralia-pas-toxic-ghost-town/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fm3wxSOqlYM

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Pennsylvania

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centralia

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Pennsylvania

- https://www.centraliapa.org/history-centralia-pa-before-1962/

- https://hudsonreview.com/2019/08/a-brief-history-of-the-huron/

- https://unchartedlancaster.com/2023/08/13/ghost-town-vs-phantom-settlement-whats-the-difference/

- https://www.heritagejohnstown.org/attractions/heritage-discovery-center/johnstown-history/history-coal-cambria-county/