You’ll find Martinsville’s downtown reflects its evolution from a thriving 1800s county seat to a modern example of urban change. While not technically abandoned, the area’s numerous vacant storefronts tell the story of its shift from whiskey and pork trading hub to a community facing economic challenges. The 1970s marked the beginning of three waves of decline, though recent I-69 development and downtown revitalization efforts signal new possibilities for this historic Indiana town.

Key Takeaways

- Martinsville has experienced significant urban decay since the late 20th century, with numerous vacant storefronts in its downtown area.

- Economic decline occurred in three waves during the 1970s-1999, causing manufacturing job losses and business closures.

- Downtown businesses have relocated to the I-69/State Road 144 interchange, leaving historic buildings empty in the city center.

- A $4 million revitalization effort started in the 1990s aims to combat urban decay and restore downtown infrastructure.

- Despite not being officially abandoned, the high number of empty storefronts and 31.4-minute average commute reflects local economic struggles.

The Rise and Fall of Downtown Martinsville

As Martinsville emerged as Morgan County’s seat in 1822, the town’s economic foundation quickly took shape through the whiskey trade of the 1830s, with eight distilleries and numerous taverns driving initial growth.

The economy then shifted to the pork trade, with flatboats carrying carcasses to New Orleans until railroads transformed transportation routes in the 1850s.

Merchants loaded pork onto flatboats bound for New Orleans, until the railroad’s arrival redirected trade routes across the Midwest.

Downtown’s golden age flourished around the 1856 red-brick courthouse, with Italianate and Commercial Vernacular buildings defining the historic square. The area gained national recognition when the Commercial District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

But by the late 20th century, urban decay had taken hold. You’d have seen theaters closing, sanitaria shutting down, and businesses moving to newer commercial zones. To avoid confusion with other locations, local historians often refer to this area as Historic Martinsville.

Despite the deterioration, there’s hope – since the 1990s, a $4 million revitalization effort and historic preservation initiatives are breathing new life into downtown’s aging infrastructure.

Urban Renewal’s Impact on Local Identity

When urban renewal swept through Martinsville in the 1960s and 1970s, it dramatically altered the city’s physical and cultural landscape.

The transformation from a city known for its mineral water resorts in the early 1900s marked a significant shift in its economic identity.

You’ll find the most profound changes in the African American business districts, where the demolition of the Baldwin Block on Fayette Street erased crucial community memory. Historic buildings that once housed thriving businesses gave way to vacant lots, severing decades of architectural heritage.

The transformation didn’t just remove buildings – it disrupted the very fabric of community life. You can see this impact in the demolished commercial centers that served as social hubs during the Jim Crow era.

While some structures, like the Martinsville Sanitarium, found new life through adaptive reuse, many community landmarks vanished forever.

Today’s suburban sprawl and decentralized commerce stand as lasting reminders of urban renewal’s reshaping of local identity. The once-bustling town square now sits half-empty, a stark contrast to its vibrant past.

The Legacy of Stepp Cemetery

You’ll find Stepp Cemetery‘s most enduring legacy in its haunting tales, particularly the legendary “Lady in Black” who’s said to maintain an eternal vigil at her family’s graves.

In the early 1900s, the cemetery gained notoriety when the Crabbite cult used the grounds for their snake-handling rituals and sacred ceremonies, adding layers of mystery to its already compelling history.

While many of the ghost stories from the 1950s through 1970s remain unverified, the cemetery’s documented history of religious fervor and tragic events continues to draw curious visitors to this remote corner of Morgan-Monroe State Forest. The site contains approximately 114 identified graves, including veterans from multiple wars. The oldest burial site dates back to 1851, marking the cemetery’s deep historical roots in Indiana.

Haunted Legends Live On

Deep within the Morgan-Monroe State Forest near Martinsville, Indiana, Stepp Cemetery stands as one of Monroe County’s most enigmatic landmarks.

Since its establishment in the early 1800s, this pioneer burial ground has become a magnet for ghostly sightings and eerie encounters. You’ll find 114 graves here, including that of Isaac Hartsock, a War of 1812 veteran, but it’s the unexplained phenomena that draw visitors to this remote location. The cemetery became part of the State Forest by 1929.

Hikers can access the site via the Three Lakes Trail, a scenic ten-mile path winding through the forest’s mysterious landscapes.

If you’re brave enough to make the forest hike, you might encounter the legendary Lady in Black mourning her lost family, or experience the mysterious electronic malfunctions that plague visitors’ devices.

Local folklore tells of a murdered girl from the 1950s whose spirit still lingers, while countless witnesses report feeling watched among the weathered headstones.

Snake Cult Mystery Remains

Perhaps the most intriguing chapter in Stepp Cemetery’s history began in the early 1900s with the arrival of William Crabb and his followers.

The Crabbites, a fringe fundamentalist group, brought their unconventional practices to this remote burial ground, including snake handling, speaking in tongues, and sacred foot washings. By 1929, they’d vanished into Brown County, but their brief presence left an indelible mark on the cemetery’s legacy.

You’ll find that while many modern ghost stories lack historical backing, the Crabbite rituals sparked genuine intrigue that persists today.

The cemetery folklore grew exponentially between the 1950s and 1970s, fueled by documented oddities like the 1966 German Shepherd incident.

Though the snake cult’s permanent presence remains unproven, their verified activities continue to fascinate visitors to this isolated forest cemetery. Today, visitors frequently report feeling of being watched while exploring the grounds.

Mother’s Eternal Graveside Watch

While Stepp Cemetery harbors many mysteries, none captivate visitors quite like the legend of the grieving mother who kept eternal watch over her family’s graves.

After losing both her husband and child, she’d spend countless hours perched upon a distinctive stump near their burial sites, maintaining her eternal vigil until her own death.

Today, you’ll find her mother’s spirit hasn’t abandoned her post. Visitors report encountering a dark-clad figure known as the “Lady in Black” wandering among the 114 pioneer graves.

She’s particularly protective of her cherished stump – local lore warns you’ll face a deadly curse within a year if you dare sit there.

Electronics malfunction mysteriously, and many experience an unmistakable sensation of being watched, suggesting this devoted mother still guards her eternal resting grounds.

Racial Climate and Community Relations

Throughout its history, Martinsville’s racial climate has been marked by significant tension and controversy. The 1968 murder of Carol Jenkins, a Black woman, cast a long shadow over the town’s reputation, while documented incidents of KKK activity and racial slurs during sporting events have reinforced these concerns. In 2002, Kenneth C. Richmond was arrested for Jenkins’ murder, finally bringing some closure to the decades-old case.

You’ll find a largely white population here, with a diversity index of just 18.6. This lack of racial awareness has led many to warn others, particularly Black visitors, against passing through the town.

The community’s reputation has been featured in major publications like Sports Illustrated and the New Yorker, highlighting the need for improved community engagement. Despite calls for change, historical legacies continue to influence local relations, with some residents expressing fear and others advocating for educational initiatives to bridge cultural divides.

Economic Shifts and Business Migration

If you walk through downtown Martinsville today, you’ll see the stark evidence of economic migration in the numerous vacant storefronts that once housed thriving local businesses.

The city’s traditional commercial hub began shifting in the late 20th century as retail corridors moved toward the outskirts, particularly along State Road 37.

You can trace this exodus through empty buildings that previously contained family-owned shops, restaurants, and professional offices – many of which have either closed permanently or relocated to newer developments outside the historic center.

Downtown Decline Patterns

The economic decline of downtown Martinsville began with three distinct waves in the late 20th century.

You’ll see how the post-war prosperity first eroded in the 1970s as international competition intensified and Vietnam War spending drained the economy. Then, the 1980s dealt another blow as supply-side economics accelerated the exodus of manufacturing jobs.

Finally, the 1999 closure of Tultex marked the third wave, leaving downtown struggling to maintain its liveliness.

Despite downtown revitalization efforts through programs like Rediscover Martinsville since 2008, you’ll find empty storefronts where businesses once thrived.

While community engagement drives volunteer initiatives to preserve historic character, the lack of diverse retail options and cultural amenities continues to challenge recovery efforts.

Today’s 31.4-minute average commute time reveals how local jobs have vanished, further weakening downtown’s economic base.

Retail Corridor Relocation

Interstate I-69’s completion through Martinsville has sparked three major shifts in retail corridor development since 2020.

You’ll notice retail evolution occurring as businesses migrate from downtown toward the interstate, particularly around the I-69/State Road 144 interchange. This shift reflects changing corridor dynamics where companies seek improved logistics and visibility.

You’re seeing businesses respond to population growth near the interstate, as new housing developments create fresh consumer bases.

The retail landscape’s transformation is driven by two key factors: direct interstate access and the influx of pass-through traffic.

Major projects at the interchange demonstrate how corridor dynamics favor highway-adjacent locations, while downtown spaces undergo renovation to accommodate modern business needs.

Martinsville’s lower operating costs and strategic location between Indianapolis and Bloomington continue attracting entrepreneurs to these emerging retail zones.

Empty Storefronts Tell Stories

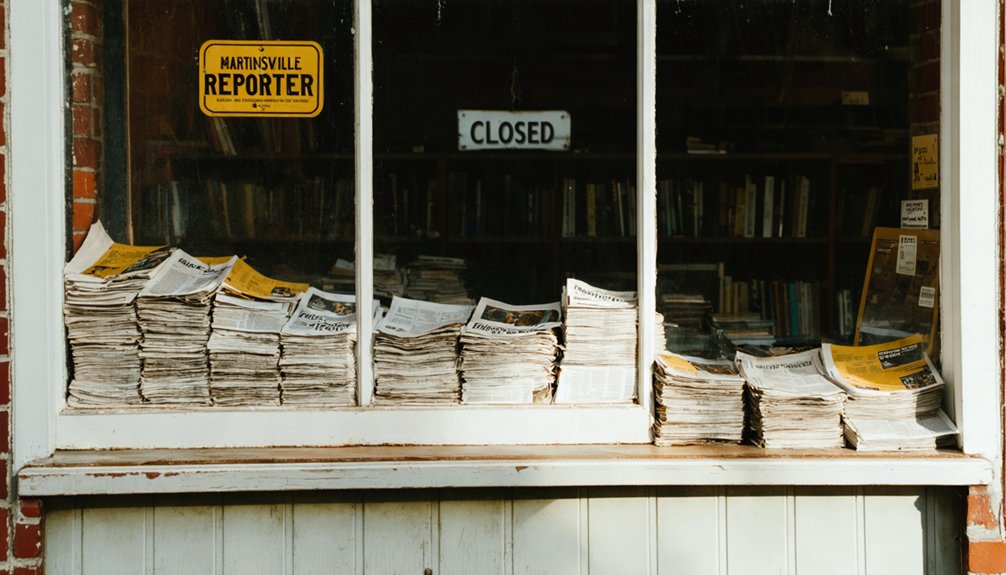

Walking through downtown Martinsville today, you’ll notice numerous vacant storefronts that chronicle the city’s economic transformation. These empty windows tell storefront stories of businesses that once thrived but couldn’t survive the changing economic landscape.

You’ll see the lasting impact of population decline and fierce competition from larger neighboring cities. The economic echoes resound through historic buildings that once housed thriving shops and local newspapers like “The Reporter.”

High operational costs and limited consumer demand have forced many small businesses to close their doors, while new enterprises hesitate to fill these spaces. The aging infrastructure and lack of business diversity reflect broader challenges, as Martinsville struggles to attract fresh investment and maintain its commercial dynamism in today’s competitive marketplace.

Paranormal Tales and Local Legends

Nestled deep within Morgan County’s wooded hills, Stepp Cemetery stands as the epicenter of Martinsville’s most enduring paranormal tales.

You’ll find a haunting collection of paranormal encounters here, from the mysterious woman in black who hums to Baby Lester’s grave to the faceless spectral man who roams the grounds.

The cemetery’s dark history took an even grimmer turn in 1966 when someone killed and hanged a German shepherd near its entrance, sparking increased reports of ghostly apparitions.

In 1966, a horrific act of animal cruelty at Stepp Cemetery’s entrance unleashed a wave of supernatural encounters.

The tragic past of the Stepp family, including the alleged murder of Reuben Stepp’s son, weaves through local folklore.

You might hear whispers about the Krabit cult’s snake-handling rituals or stories of the Hacker children, whose young lives ended too soon, leaving their restless spirits to wander these sacred grounds.

The Decline of Local Journalism

When Gannett acquired the Reporter-Times in 2019, Martinsville’s 130-year tradition of local journalism began its rapid decline.

The new corporate owners didn’t reinvest in local reporting staff, and by 2022, your community lost its last local journalist, creating an information vacuum where news about city council, schools, and law enforcement once thrived.

But you wouldn’t let this journalism crisis destroy your access to local news.

When the Morgan County Correspondent launched as an independent weekly newspaper, nearly 2,000 of you stepped up with paid subscriptions within six months.

Your strong community engagement proved that small-town journalism isn’t dead – it just needs proper support.

While newspapers nationwide continue closing at 2.5 per week, you’ve shown that print journalism can thrive when communities fight to preserve it.

Historic Architecture and Lost Grandeur

Beyond the headlines and newsprint that once chronicled Martinsville’s story lies the physical evidence of the town’s golden age – its historic architecture.

You’ll find the red brick Italianate courthouse, designed by Isaac Hodgson between 1856-1859, standing as one of Indiana’s few pre-Civil War judicial buildings. Along East Washington Street, 64 historic buildings showcase the architectural significance of Queen Anne, Classical Revival, and Colonial Revival styles from 1869 to 1940.

Grand mansions that once housed prominent families along Washington Street reflect the lost affluence of this mineral water boomtown. While urban renewal and suburban expansion diminished the town square’s vibrancy after 1945, historic preservation efforts continue to salvage these architectural treasures, from the 1917 City Hall to the repurposed county jail complex.

Present-Day Reality and Community Change

Although Martinsville’s historical grandeur has faded, today’s community paints a picture of resilience and adaptation.

You’ll find a blend of old and new businesses breathing life into the downtown area, where the iconic red brick courthouse still stands sentinel over community events and outdoor performances.

The city’s cultural revitalization is evident in its population of 12,000, who’ve maintained strong ties to their basketball heritage and mineral water history.

While the Reporter-Times may have become a “ghost newspaper,” the community’s resilience shines through its festivals, local attractions, and growing business sector.

You’ll discover a city that’s strategically positioned between Indianapolis and Bloomington, leveraging its location to foster economic growth while preserving its small-town charm through thoughtful development initiatives.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to Martinsville’s Original Train Station?

You’ll be amazed – the massive train station’s still standing! Built in 1911, it served passengers until 1940, became a freight depot, housed the Chamber of Commerce, and now proudly hosts the Arts Council.

Are There Any Annual Festivals or Community Events in Martinsville Today?

You’ll find plenty of festival highlights year-round, from July’s County Fair and October’s Fall Foliage Festival to downtown’s Holiday Cookie Stroll. Major community gatherings include summer concerts and seasonal holiday celebrations.

How Many Schools Currently Operate Within Martinsville City Limits?

You’ll find 10 active public schools within city limits, offering educational programs from Pre-K through grade 12, with a total school enrollment of 4,081 students under MSD Martinsville’s administration.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Martinsville Area?

You’ll find the Miami tribe was the primary Native Tribe, with Delaware Indians establishing villages later. The Wyandot hunted nearby, while the region’s Cultural Heritage includes influences from Potawatomi, Wea, and Piankashaw peoples.

When Was the Last Time Martinsville Elected a Female Mayor?

Through the halls of female leadership and election history, you’ll find that 2016 marks the first and most recent time a female mayor was elected, when Shannon Kohl became the pioneering choice.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4w5NTHqj_fA

- https://justice.tougaloo.edu/sundowntown/martinsville-in/

- https://www.idsnews.com/article/2024/08/ghost-newspaper-town-fight-indiana

- https://www.indianahauntedhouses.com/real-haunt/stepp-cemetery-at-morganmonroe-state-forest.html

- http://www.greatamericanghosttour.co.uk/Pages/Indiana/Martinsville.html

- https://bloomingtonthenandnow.wordpress.com/2013/08/04/martinsville-old-mansions-and-a-quiet-square/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WtR1SB2Jjnc

- https://indyencyclopedia.org/martinsville/

- https://martinsvillechamber.com/wp-content/uploads/custom_files/DwntnRevival_Chapter1.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martinsville