You’ll find Indio’s remains near Eagle Pass, Texas, where William and Jane Cazneau established trading posts along the Rio Grande in the 1850s. The settlement grew into Indio Ranch by 1880, featuring cattle operations and a thriving community with a post office, hotel, and schoolhouse by 1912. Environmental challenges and economic decline led to its abandonment by 1936, though preservation efforts since the 1960s have worked to protect its remaining structures and rich vaquero heritage.

Key Takeaways

- Indio began as a trading post in the 1850s and evolved into a ranching community with a post office established in 1880.

- The community thrived until 1936, featuring a schoolhouse, hotel, and agricultural operations centered around the Chihuahua Trail.

- Natural disasters, economic decline, and reduced agricultural viability led to the town’s eventual abandonment.

- The post office’s closure in 1936 marked a significant turning point in Indio’s decline from a bustling community to a ghost town.

- Preservation efforts since the 1960s focus on protecting remaining structures and documenting Indio’s rich ranching heritage.

Origins of the Cazneau Ranch Legacy

While many Texas ranches emerged during the mid-1800s, the Cazneau Ranch stood apart through its founders’ remarkable influence on frontier development.

You’ll find the ranch’s origins deeply rooted in the pioneering spirit of William Leslie Cazneau and his wife Jane McManus Storm Cazneau, who established their operation near Eagle Pass in the 1850s.

The Cazneau legacy extended far beyond typical ranching, as they built essential trading posts along the Rio Grande that shaped Texas-Mexico commerce. Their economic impact transformed the region, with the ranch becoming central to Indio’s establishment and growth. Early Spanish explorers like Alonso De León had traversed this same area in their 1690 expeditions.

The Cazneaus weren’t just ranchers – they were diplomats, entrepreneurs, and adventurers who ventured into Cuban affairs and even experimented with using camels in the American Southwest. The area later became the site of the Cross S Ranch colonization in 1908, marking a new chapter in the region’s development.

The Birth of Indio Ranch (1880)

The establishment of Indio Ranch marked a significant change in Presidio County’s development when it emerged around 1880, centered on cattle operations and positioned along the essential Chihuahua Trail.

You’ll find the ranch’s early history intertwined with John W. Spencer’s settlement efforts after 1854, though the area wouldn’t adopt the name “Indio” until the establishment of its post office in 1880.

Similar to the path of Casa Piedra settlement that emerged in 1883, Indio Ranch evolved into a key community anchor in the region.

Through the early ranching period, you can trace the property’s evolution from raw ranchland to an emerging community hub, complete with a hotel and cleared agricultural sections by 1910. The property would later become part of an important research station when Frank B. Cotton contributed the land for educational purposes.

Ranch Origins and Settlement

Following Spanish land grants and cattle ranching traditions dating to the mid-1700s, ranching activity in what would become Indio emerged after John W. Spencer settled the area post-1854.

Initially known as Paloma Ranch and Spencer’s Rancho, the land officially became Indio Ranch around 1880, coinciding with the local post office’s name change.

The ranch’s development reflected the deep vaquero heritage of South Texas, as settlers from Mexico’s northeastern regions brought their expertise in managing cattle in arid environments. Like other ranches in the region, workers resided in simple one-room jacales while tending to daily operations.

You’ll find that these early ranchers, despite facing indigenous conflicts and frontier challenges, established sustainable operations by 1910, complete with a drilled well and basic infrastructure.

Their cattle branding practices and ranching techniques, borrowed from Spanish-Mexican traditions, helped shape the American cattle industry along the Rio Grande. The emergence of land grant systems under Spanish rule in the 18th century had provided the foundation for these ranching establishments.

Cazneau’s Land Purchase History

During Texas’s early land acquisition period, Jane McManus Storm Cazneau emerged as a pioneering force in establishing what would become Indio Ranch, finalizing critical purchases by 1833 through the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company in San Felipe.

Despite Mexican law prohibitions on certain land sales, Cazneau transactions proceeded through strategic use of land scrip sold at five cents per acre.

Key aspects of Cazneau’s land acquisition included:

- Securing portions of eleven-league Mexican land grants totaling approximately 48,712 acres

- Maneuvering complex legal challenges during territorial shifts

- Managing border region holdings that would influence settlement patterns

The area would later become part of a significant historical narrative documented in “The Chronicles of Tap” featuring Eagle Pass cowboys and their pursuit of justice in the region. By 1880, the property had transformed into the Indio Ranch with approximately thirty residents.

Early Ranching Operations Established

As Spanish and Mexican ranching traditions converged with Anglo-American practices in 1880, Indio Ranch emerged among a wave of cattle operations expanding into Texas’s frontier regions.

You’ll find the ranch’s early operations deeply rooted in centuries-old techniques brought by settlers from Queretaro, Nuevo Leon, and Coahuila. These ranching techniques included traditional branding, ear-marking, and cattle handling methods passed down from Spanish colonial times. The abundant grasslands of the region provided ideal conditions for sustaining large herds.

Like other frontier ranches, Indio’s cattle operations faced significant challenges. You’d have witnessed ranchers battling extreme weather events, managing the shift from open range to fenced grazing, and dealing with territorial disputes. The introduction of barbed wire fencing transformed how ranchers controlled and managed their herds.

The ranch’s daily life reflected a rich blend of cultural influences, with vaqueros, Native Americans, and Anglo ranchers contributing their skills while women played crucial roles in operational management.

Early Settlement and Community Development

While Native Americans had inhabited the Texas region for millennia, the settlement of Indio emerged in the late 19th century near Tortuga Creek, approximately eight miles east of present-day Crystal City.

Settlement patterns centered around water access, with early community dynamics shaped by the need for protection and self-sufficiency.

The settlers established key infrastructure elements:

- Adobe homes and protective corrals to guard against raids

- Small chapels serving as religious and social gathering points

- One-room schoolhouses educating dozens of local children by 1908

Mexican farming families formed the core of Indio’s early population, cultivating crops and raising livestock while adapting to the semi-arid environment.

They created a resilient community that balanced subsistence agriculture with market trade, taking advantage of the region’s natural resources despite challenging frontier conditions.

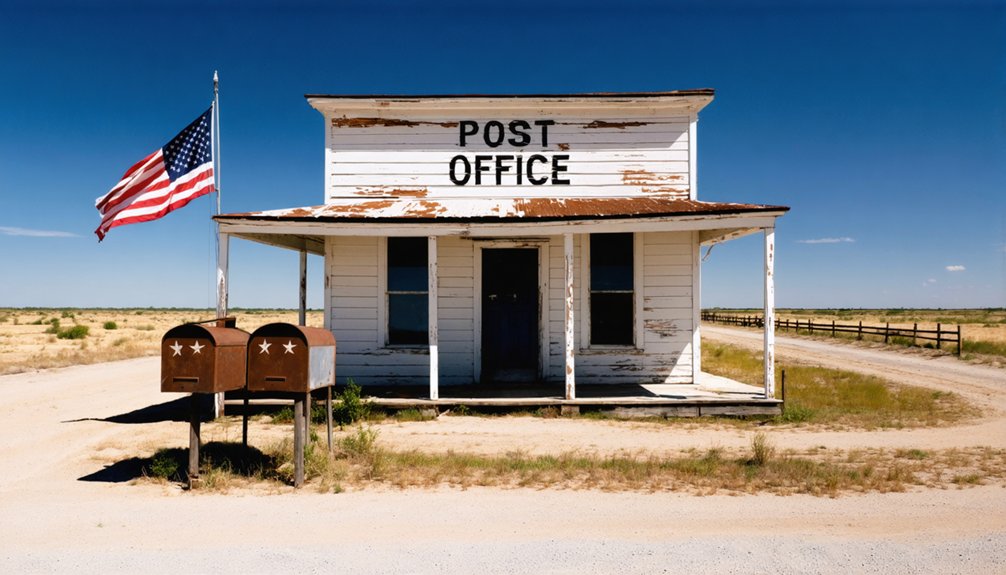

Life Around the 1912 Post Office

You’d find early mail operations in Indio centered around the newly established 1912 post office, where Mr. Holtewanger served as one of the first postmasters coordinating deliveries by horseback and stagecoach across the rural Zavala County terrain.

The post office quickly became the community’s central mail collection point, processing everything from personal letters to government notices and commercial catalogs that helped connect isolated ranching families to the outside world.

Regular postal routes linked scattered homesteads and remote ranches to larger nearby towns, providing essential communication services that helped sustain the frontier settlement’s development.

Early Mail Delivery Operations

When Indio’s post office opened its doors in 1912, it marked a pivotal moment for this small Zavala County community. Under Postmaster Holtewanger‘s supervision, mail routes operated primarily via stagecoach and early automobiles, battling the region’s rugged terrain and unpredictable weather.

You’d find delivery schedules typically running twice weekly, connecting isolated ranchers and settlers to the outside world.

The basic but essential mail delivery operations included:

- Manual sorting and processing of letters, catalogs, and parcels in the modest facility

- Coordination of incoming and outgoing deliveries through detailed ledger tracking

- Operation of important money order and parcel services for local commerce

The delivery challenges were constant, with carriers traversing long distances between settlements while maintaining critical communication links for this growing frontier community.

Community Mail Collection Hub

As Indio’s central gathering point, the 1912 post office served far more than its basic mail functions – it became the town’s vibrant social hub.

Under postmasters like Mr. Holtewanger and Charles S. Murphy, you’d find residents gathering daily to collect their mail, share local news, and discuss everything from agricultural updates to community events.

The post office’s strategic location near key roads fostered community connections, making it accessible to both town residents and ranch workers.

You’d witness the postal significance firsthand as ranchers and merchants conducted business through reliable mail services, ordering supplies and receiving payments vital for their isolated operations.

When you visited, you’d likely find the building doubling as a general store or ranch office, typical of remote Texas towns, creating an essential nexus of frontier life until its closure in 1936.

The Schoolhouse Years

The one-room clapboard schoolhouse, built in 1909 at the intersection of Oasis and Bliss avenues, marked a significant milestone in Indio’s educational history.

Indio’s 1909 one-room schoolhouse stood proudly at Oasis and Bliss, shaping the town’s future through education and community.

This second educational building in the area would shape the schoolhouse legacy for generations, with its iconic cast-iron bell donated by Southern Pacific Railroad becoming a symbol of educational impact and community perseverance.

You’ll find the schoolhouse served as more than just a learning center:

- It provided K-8 education for children of Dust Bowl migrants and itinerant farm workers

- It helped transform transient agricultural laborers into permanent community members

- It supported the region’s booming agricultural economy through basic skills education

The schoolhouse became a cornerstone of community life, helping Indio evolve from a simple railroad stop into a thriving agricultural town.

Ranching Culture and Local Economy

Spanish settlers from Nuevo Leon and Coahuila introduced ranching to South Texas in the mid-18th century, establishing the foundations for Indio’s pastoral legacy.

You’ll find that ranching traditions quickly became the economic backbone of the region, with ranches serving as both social hubs and essential business centers.

As you explore Indio’s history, you’ll see how ranching shaped the community’s character through multi-generational family involvement and frontier survival skills.

The economic shifts became evident by 1950 when the town’s infrastructure, including hotels, transformed into ranchhouses.

While the railroad’s decline affected market access, some operations like Faith Ranch adapted by consolidating smaller properties.

Though Indio eventually became a ghost town, its ranching heritage left an indelible mark on Texas’s cattle industry leadership.

The Path to Abandonment

When devastating natural disasters struck the Texas Gulf Coast in the late 19th century, they set a precedent for how environmental calamities could trigger town abandonment – a fate that would eventually befall Indio.

You’ll find that Indio’s path to becoming a ghost town followed familiar patterns seen across Texas, where abandonment causes often stemmed from multiple factors converging.

The social dynamics of the community began unraveling as economic opportunities dwindled, particularly when the region’s ranching prospects diminished.

Key factors that sealed Indio’s fate:

- Dependence on a single industry (ranching) left the town vulnerable when that sector declined

- The post office’s establishment in 1912 couldn’t prevent the eventual erosion of community infrastructure

- Shifting migration patterns drew settlers away to more promising locations, depleting the town’s population

Traces Left Behind: What Remains Today

Modern visitors to Indio will encounter five distinct categories of physical remains: deteriorating building ruins, a historic cemetery, rugged desert terrain, privately-owned parcels, and traces of former infrastructure.

The architectural remains consist of roofless structures, scattered foundations, and weathered rubble that tell the story of this once-thriving settlement.

Time-worn walls and crumbling stone foundations stand as silent witnesses to the bustling community that once called this place home.

You’ll find the cemetery serves as the site’s most prominent landmark, with its weathered tombstones offering glimpses into the lives of past residents.

The surrounding desert landscape has steadily reclaimed the town, while multiple private landowners now control access to various sections.

Despite its historical significance, you won’t find modern amenities or maintained roads – just raw, untouched ruins accessed by rough paths, creating an authentic ghost town experience that captures the essence of abandoned Texas settlements.

Comparing Indio to Other Texas Ghost Towns

Unlike mining-dependent ghost towns such as Terlingua that experienced sudden economic collapse when mineral resources were depleted, Indio’s abandonment followed a more gradual pattern typical of small farming and ranching communities.

You’ll find that Indio’s slower decline, marked primarily by its 1912 post office establishment and eventual closure, contrasts sharply with the dramatic endings of places like Indianola, which was violently destroyed by hurricanes in 1875 and 1886.

While many Texas ghost towns rose and fell with the fortunes of single industries like mining or shipping, Indio’s story reflects the quieter dissolution of rural communities as changing agricultural patterns and population shifts transformed the Texas landscape.

Unique Abandonment Patterns

Through its distinctive pattern of abandonment, Indio, Texas stands apart from many ghost towns across the Lone Star State. The town’s slow decline due to water scarcity and agricultural challenges created a unique abandonment pattern that differed from the dramatic endings of storm-ravaged coastal settlements or boom-bust mining towns.

Unlike other Texas ghost towns, Indio’s distinctive features include:

- Gradual depopulation over decades rather than sudden abandonment

- Well-preserved structures due to its desert location and slower decay

- Agricultural-focused ruins instead of industrial remnants

You’ll find Indio’s abandonment causes deeply rooted in environmental stress and diminishing farm productivity, not resource depletion or technological shifts.

The population trends followed a steady downward trajectory, reflecting the harsh realities of desert farming rather than the abrupt collapses seen in mining or port towns.

Mining Versus Ranching Decline

The contrasting fates of Texas ghost towns reveal stark differences between mining and ranching settlements, with Indio’s agricultural decline following a markedly different pattern than its mining counterparts.

While mining towns like Shafter and Terlingua experienced sudden population crashes when mineral deposits were depleted, ranching communities faced a more gradual descent into abandonment.

You’ll find that mining decline occurred rapidly, with towns losing thousands of residents almost overnight after mine closures.

In contrast, ranching decline, which affected towns like Indio, happened over decades as water sources diminished and agricultural economics shifted.

Mining towns were also more isolated and dependent on single industries, while ranching settlements typically maintained diverse agricultural economies until environmental challenges, particularly water scarcity, ultimately rendered them unsustainable.

Preserving Indio’s Historical Record

Since the 1960s, dedicated local groups have spearheaded efforts to preserve Indio’s historical legacy through systematic documentation and physical conservation.

Local champions have worked tirelessly since the 1960s to protect and document Indio’s rich historical heritage for future generations.

You’ll find community involvement has played an essential role in protecting the town’s remaining structures while guaranteeing historical documentation remains accurate and thorough.

Key preservation initiatives include:

- Installing modern amenities in historic buildings to maintain their functionality

- Creating educational programs that connect students with local history

- Establishing partnerships with museums and schools for interactive tours

While facing challenges like limited funding and harsh environmental conditions, preservation groups haven’t wavered in their commitment.

They’re working within legal frameworks to protect artifacts while making the site accessible for future generations.

The combination of strict preservation policies and educational outreach guarantees Indio’s story won’t be lost to time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Peak Population of Indio During Its Most Prosperous Years?

While you might expect dramatic population shifts from economic decline, you can’t definitively know the peak beyond 263 residents recorded in 2000, as earlier census data doesn’t exist for this community.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Lawlessness in Indio’s History?

You won’t find documented crime sprees or outlaw activity specific to Indio’s history in the available records. The town’s troubles appear more economic and demographic than criminal in nature.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Indio Area?

You’ll find the Coahuiltecans were the primary inhabitants of Indio’s area, while Karankawa and Atakapa tribes lived nearby. These Native communities faced severe displacement during Spanish mission expansion and colonization.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Ever Visit or Stay in Indio?

You won’t find documented evidence of famous visitors to Indio in historical records. While historical events occurred in the region, no prominent figures’ visits or stays are verified in available sources.

What Natural Disasters, if Any, Contributed to Indio’s Eventual Abandonment?

Unlike Indianola’s hurricane destruction, you won’t find dramatic flood damage or drought impact in Indio’s story. The town’s decline came from simpler causes: changing railroad routes and dwindling economic opportunities.

References

- https://livefromthesouthside.com/10-texas-ghost-towns-to-visit/

- https://mix941kmxj.com/see-how-two-texas-ghost-towns-battled-for-the-county-and-lost/

- https://www.southernthing.com/ruins-in-texas-2640914879.html

- https://knue.com/texas-gulf-ghost-town-indianola/

- https://www.texasalmanac.com/places/indio-0

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/el-indio-tx

- https://www.texasescapes.com/SouthTexasTowns/El-Indio-Texas.htm

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TexasGhostTowns/IndianolaTexas/IndianolaTx.htm

- https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc278486/m2/1/high_res_d/1002658825-hudson.pdf