You’ll find Kimball’s ghost town remnants at the historic Brazos River crossing in Bosque County, Texas. Founded in 1853 by Judge John Kimball, this settlement became a vital waypoint on the Chisholm Trail from 1867 to 1884, seeing up to 3,000 cattle cross daily. When the railroad bypassed Kimball in 1881, the town’s economy collapsed. Today, Kimball Bend Park preserves the site with granite markers and interpretive signs that reveal its fascinating frontier story.

Key Takeaways

- Kimball was established in 1853 by Judge John Kimball near the Brazos River as a settlement focused on agriculture and trade.

- The town thrived during the Chisholm Trail era (1867-1884) as a major cattle crossing point, handling thousands of longhorns daily.

- When railroads bypassed Kimball in 1881, trade routes shifted to neighboring towns, triggering the settlement’s economic decline.

- The loss of cattle drive business and rail access caused merchants and residents to relocate, transforming Kimball into a ghost town.

- Today, only historical markers at Kimball Bend Park remain, commemorating the town’s significance in Texas ranching history.

The Birth of a Frontier Settlement

While westward expansion swept across Texas in the mid-19th century, the frontier settlement of Kimball emerged in 1853 under the guidance of Judge John Kimball, a New York settler who acquired local property from Jacob DeCordova.

Driven by westward expansion, Judge John Kimball established the Texas frontier settlement of Kimball in 1853 after acquiring DeCordova property.

You’ll find that the settlement dynamics of early Kimball reflected the pioneering spirit of its founders. Judge Kimball, along with Richard B. Kimball and Jacob Raphael de, strategically positioned the town near essential waterways and trade routes in Bosque County.

They laid out and platted the settlement to establish agricultural foundations that would sustain future growth. The town’s location near what’s now Kimball Bend Park proved ideal for farming and ranching operations. Much like Henry Kimball’s founding of Tascosa in 1876, the town was established to support growing regional trade activities.

Early settlers, mostly from eastern states, built homes and trade outposts, creating a self-sufficient community focused on grain production and feed businesses. This agricultural focus would later inspire Kay Kimbell to establish the Kimbell Feed Company, which became a cornerstone of Fort Worth’s industrial growth.

Life Along the Brazos River

As settlers established themselves along the Brazos River in 1825, the waterway’s distinctive horseshoe curve at Kimball Bend became a significant geographic landmark for the region’s development.

You’ll discover how this essential crossing point shaped frontier life, as settlers faced the stark realities of transforming wilderness into civilization.

Life along the Brazos presented a complex mix of agricultural aspirations and frontier hardships:

- Fertile riverbottom lands attracted ambitious colonists seeking farming opportunities

- A shallow ford provided the best river crossing for miles, making it a natural stopping point

- British settlers from Kent attempted to establish a “Philadelphia on the Brazos”

- Middle-class colonists struggled to adapt from urban life to wilderness conditions

- Local trade flourished briefly as travelers used the crossing for cattle drives

The Kechi Indians had previously inhabited the area before the colonists arrived.

Sir Edward Belcher’s failure to provide provisions for the settlers contributed significantly to the colony’s eventual collapse along the Brazos.

The Chisholm Trail’s Golden Era

You’ll find that Kimball’s strategic position on the Chisholm Trail made it a vital crossing point during the trail’s peak period from 1867 to 1884.

The town saw countless herds of Texas Longhorns pass through, with trail bosses coordinating their crossings to guarantee adequate water and grazing for the massive cattle drives. Each drive was managed by a trail boss and crew consisting of 8-10 cowboys, a cook, and a chuck wagon serving as the central hub. The economic incentive was clear, as cattle worth four dollars in Texas could fetch ten times that amount in northern markets.

As thousands of cattle moved northward through Kimball, trail traffic reached its zenith in the early 1870s when up to 600,000 head of cattle per year traversed this section of the historic route.

Trail Crossing Peak Period

During the Chisholm Trail‘s golden era of the 1870s, Kimball’s strategic Brazos River crossing served as an essential waypoint for the massive cattle drives heading north to Kansas.

You’d find this location particularly valuable for cattle fording, thanks to its hard sand banks and gentle slopes that eliminated quicksand risks. The site’s trail logistics were masterfully designed to handle the daily movement of thousands of Texas longhorns. Barbed wire fencing eventually brought an end to the open range cattle drives in the 1880s.

- Large herds crossed safely at the natural ford without risk of losing cattle

- Cowboys could rest their herds while trading with local settlers

- The Kimball ferry, established in 1865, provided an alternative crossing method

- Average daily progress of eight miles made Kimball an ideal stopping point

- Local agreements with Native American tribes guaranteed peaceful passage through the territory

The crossing point’s significance grew as part of the five million cattle that moved through the Chisholm Trail during its active years.

Cattle Drive Traffic Surge

When the Chisholm Trail reached its zenith between 1867 and 1875, massive herds of 2,500 to 3,000 cattle thundered through Kimball’s crossing daily.

You’d find herds strategically spaced less than 10 miles apart, with each trail boss coordinating nightly stops at watering points to maintain this careful spacing. The experienced crews managed these large herds with remarkable efficiency.

The cattle drive dynamics were staggering – over 2.4 million cattle moved north during these peak years, transforming $5 Texas longhorns into premium-priced beef at Kansas railheads. Once reaching their destination, cattle prices soared to $40 per head.

Trail boss responsibilities included managing crews of 10-14 cowboys working round-the-clock shifts, while the innovative chuckwagon kept supplies moving.

You’d see the cattle walking 10-15 miles daily, balancing speed with the need to maintain marketable weight as they pushed toward lucrative markets in Abilene, Newton, and Wichita.

A Thriving River Crossing Community

Established in 1853, Kimball rapidly grew into a bustling community thanks to its strategic location on the west bank of the Brazos River. The settlement dynamics centered around a vital ford where gentle, sloping banks provided safe passage.

Community interactions flourished as the town became a natural convergence point for diverse frontier travelers.

- You’d find a reliable ferry service operating from 1865 to 1915

- The shallow crossing point was free of dangerous quicksand

- Local commerce thrived from constant wagon and cattle drive traffic

- The site sat near the 98th meridian, an important geographic marker

- Agricultural and ranching activities supplemented the crossing trade

The town’s position several miles north of Kopperl made it an ideal rest stop for cattle drivers, merchants, and settlers moving westward, creating a vibrant hub of frontier activity.

The Winds of Change: Economic Shifts

You’ll find that Kimball’s fortunes took a dramatic turn when the railroad bypassed the town in 1881, redirecting crucial trade routes through neighboring Brownfield instead.

The loss of rail access coincided with the end of the great cattle drives, which had been the lifeblood of Kimball’s economy through its early years.

These two economic shifts dealt a devastating blow to the town, as merchants and residents began relocating to better-connected communities with stronger commercial prospects.

Railroad Reshapes Local Trade

During the late 1870s, the Santa Fe Railroad‘s decision to bypass Kimball proved catastrophic for the town’s future.

The railroad’s choice to cross the Brazos River near Kopperl, about three miles away, created devastating trade disruption that you’d witness through rapidly declining commerce and population.

- Your once-bustling Chisholm Trail trade post lost its economic backbone

- Rail-connected towns like Kopperl gained the commercial advantage

- Local stores and saloons saw their cattle drive customers vanish

- Transport costs skyrocketed without direct rail access

- Market reach became severely limited compared to rail-served communities

The railroad impact reshaped local trade patterns completely.

While the Texas economy modernized through rail networks in the 1880s, Kimball’s isolation from this vital infrastructure spelled its doom.

Without adaptation options, the town’s businesses closed, population dwindled, and by 1910, Kimball became another Texas ghost town.

Cattle Industry’s Swift Decline

The railroad’s devastating impact on Kimball coincided with broader upheavals in the Texas cattle industry.

You’d have witnessed the catastrophic “Great Die-Up” of 1886-87, when severe winter storms killed thousands of cattle, shattering the open-range model that had dominated the region.

Cattle overgrazing had already weakened the industry’s foundation, depleting grasslands and degrading soil quality across Texas ranges.

As railroad expansion made long cattle drives obsolete, economic consolidation reshaped the landscape – large cattle barons bought out smaller operations, while surviving independent ranchers shifted to more intensive management practices.

You’d have seen the transformation firsthand: barbed wire replacing open ranges, windmills dotting the landscape, and many ranchers diversifying into sheep herding.

Legacy and Modern-Day Remnants

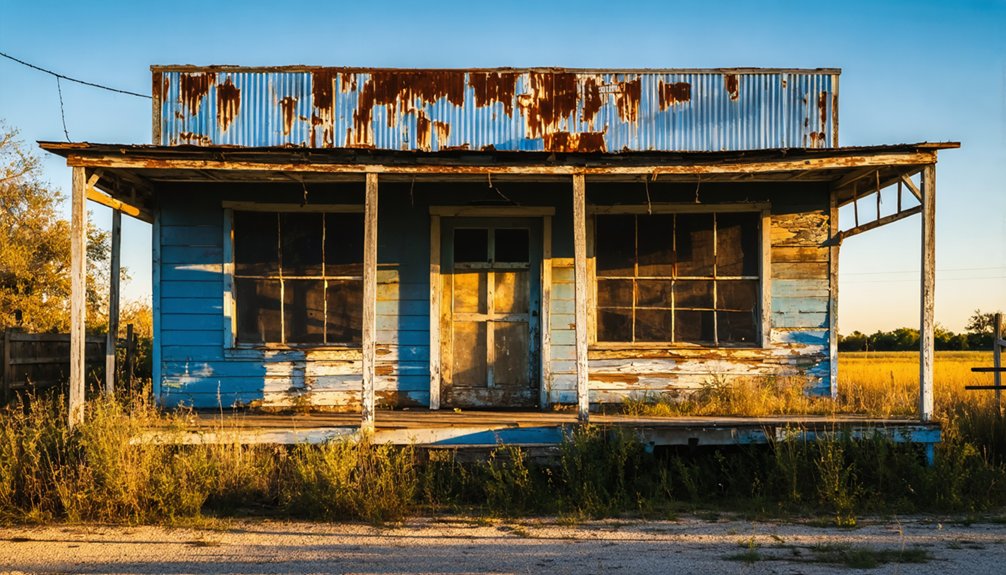

While Kimball’s physical structures have largely vanished, its legacy endures through historical markers and its role in Texas frontier history.

The ghost town’s heritage lives on at Kimball Bend Park, where you’ll find state-approved pink granite markers commemorating this once-bustling frontier settlement.

Though Kimball’s buildings are gone, its spirit remains etched in pink granite markers at Kimball Bend Park, preserving frontier memories.

- Texas State Historical Marker No. 836, installed in 1963, marks the site’s significance

- The original Chisholm Trail crossing point remains visible through interpretive signs

- You can explore the park’s trails that follow historic cattle drive routes

- Educational displays highlight the town’s importance during Texas’ ranching era

- The site serves as a symbol of how changing transportation patterns shaped the American frontier

Today, you’re free to walk these grounds and connect with a pivotal piece of Texas history that helped shape America’s westward expansion.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Notable Gunfights or Lawless Incidents in Kimball’s History?

You’ll find evidence of gunfights through wound records and lawlessness incidents in the settlement’s past, but unlike nearby towns like Tascosa, there aren’t specific documented famous shootouts from Kimball’s history.

What Happened to the Original Residents When the Town Declined?

Like leaves scattered by autumn winds, residents drifted away as the town declined. You’d find they moved to nearby communities until 1947, when the government’s Lake Whitney project forced out the last inhabitants.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Pass Through Kimball?

While Kimball’s historical significance lies in the Chisholm Trail cattle drives, you won’t find records of specific famous visitors passing through, though countless unnamed cowboys traveled this frontier path.

What Was the Peak Population of Kimball During Its Heyday?

Though early Texas towns often saw dramatic population growth, you’ll find no exact peak count recorded. Based on town demographics like multiple stores and 600+ cemetery burials, estimates suggest several hundred residents during the late 1800s.

Are There Any Preserved Artifacts From Kimball in Local Museums?

You won’t find artifact preservation from Kimball at the Kimbell Art Museum, but you’ll need to check Bosque County’s local historical societies and archives for any existing local exhibitions.

References

- https://texashistoricalmarkers.weebly.com/chisholm-trail-kimball-crossing.html

- https://www.ghostsandgetaways.com/ghost-towns

- https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth178898/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/tx/kimball.html

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/kimball-tx

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TexasGhostTowns/KimballTexas/kimballtx.htm

- https://petticoatsandpistols.com/tag/ghost-towns/

- https://www.fortwortharchitecture.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=3088

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.bosquecounty.gov/163/History-of-Bosque-County