You’ll find Knik’s ghost town ruins near Alaska’s Knik Arm, where this once-thriving frontier settlement began in the 1880s. Founded at a Dena’ina village site, Knik grew into a major trading hub during the Gold Rush era, supporting 500 residents with hotels, saloons, and stores by 1915. The town’s fate changed dramatically when the Alaska Railroad bypassed it, leading to its rapid decline. The abandoned site now holds fascinating traces of Alaska’s pioneering past.

Key Takeaways

- Knik was a bustling gold rush town in Alaska that peaked at 500 residents in 1915 with hotels, saloons, and essential services.

- The town was originally established by George W. Palmer in the 1880s and served as a major supply hub for miners.

- The Alaska Railroad’s construction bypassing Knik led to the town’s rapid decline and eventual abandonment as a commercial center.

- Historic buildings from Knik have been relocated to nearby Wasilla to preserve the town’s gold rush era heritage.

- The ghost town’s cultural preservation is now managed through the Alaska Knik Tribe and Matanuska-Susitna Borough’s Historic Preservation Plan.

The Birth of a Trading Post

Nestled along the Knik River, a pivotal chapter in Alaska’s commercial history began when George W. Palmer established the first American trading post in the 1880s.

You’ll find its trading post origins at a Dena’ina village called “Kinik,” where 46 Athabascan Indians made their home according to the 1880 census.

Early commerce at the post served multiple purposes, becoming a crucial supply point for local Native populations, explorers, and settlers pushing into the frontier.

The trading post emerged as a vital lifeline, supplying diverse groups who called this rugged Alaskan frontier their home.

The town’s infrastructure grew to include deep-draft vessel docks to facilitate the increasing trade activities.

The discovery of gold in the early 1890s brought a wave of Cook Inlet stampeders seeking fortune in the region.

The trading activities expanded as trappers, miners, and homesteaders sought essential goods for their ventures.

When the Alaska Commercial Company opened a store during this period, it marked the beginning of larger-scale commerce in the area.

Later, Orville Herning’s Knik Trading Company would take over ACC’s operations, further cementing Knik’s role as a commercial hub.

Dena’ina Heritage and Early Settlement

Long before Palmer established his trading post, the Dena’ina Athabascans shaped the cultural landscape of south-central Alaska.

The K’enaht’ana, part of the larger Dena’ina culture, called the Knik Arm area home for thousands of years, establishing their territory between the Chugach and Talkeetna Mountains. You’ll find their traditional practices deeply rooted in the region’s seasonal rhythms. The tribes lived in communal dwellings called Nichił dwellings.

Living along Nuti (Knik Arm), they followed a sophisticated annual cycle of resource gathering.

Spring brought camps near Chester Creek and Ship Creek for waterfowl and eulachon fishing. Summer saw them moving to Fish Creek and other tributaries, while careful storage of supplies helped them survive harsh winters. Village leaders known as geshga regulated salmon harvesting to ensure fair distribution among the community.

Despite later Russian contact and devastating epidemics, the Dena’ina maintained their independence and cultural identity until 1867.

Gold Rush Transforms Knik

You’ll find that Knik’s transformation during the Klondike Gold Rush began with a burst of commercial activity as prospectors flooded the Cook Inlet region in search of riches.

The town’s position as a crucial supply and transportation hub made it an essential stopover for miners heading to Alaska’s interior, spurring the rapid growth of trading posts and auxiliary services. The arrival of the S.S. Portland in 1897 with its cargo of Klondike gold intensified the flood of prospectors through the region. Most travelers faced a grueling journey requiring 90 days to reach their destination.

While Knik initially thrived on this surge of gold-seeking traffic, its prominence proved short-lived as alternative routes through Skagway and Dyea drew prospectors away from Cook Inlet’s shores.

Thriving Trade and Commerce

The discovery of gold in Alaska’s Talkeetna Mountains and Iditarod River districts transformed Knik into a bustling commercial hub during the early 1900s.

You’d find essential mining supplies at the town’s hardware stores and trading posts, while roadhouses and hotels provided shelter for weary prospectors. The Knik Trading Company emerged as the area’s leading merchant, offering everything from tools to tobacco. The Alaska Commercial Co. established the first major trading operation in 1882. Like the merchants of two tons of gold arriving in Seattle that sparked the Klondike rush, these shipments fueled local economic growth.

As gold poured in from the Iditarod region, often exceeding a ton per shipment, Knik’s trade dynamics flourished. The town served as a vital gateway between remote mining areas and southern supply routes, with dog sled convoys maneuvering the challenging terrain.

Miners Flood Cook Inlet

When gold was discovered along Cook Inlet’s Turnagain Arm in the early 1890s, thousands of ambitious prospectors flooded into Alaska’s newest mining frontier.

By 1896, you’d have found over 3,000 men working the gravels at Canyon Creek and throughout the Turnagain Arm region. A.J. Mills and George Donaldson were the first to stake claims on Sixmile Creek, leading to the formation of the Sunrise mining district in 1895.

The gold mining boom transformed Sunrise City into a bustling settlement of up to 2,000 people, complete with saloons, stores, and social centers. The town served as the Judicial Center for Cook Inlet. Large steamers transported miners from Seattle to Tyonek for a forty dollar fare.

Yet prospecting challenges were evident – between 1897 and 1914, areas like Willow Creek yielded only $30,000, proving that striking it rich wasn’t guaranteed in this rugged frontier.

The Boom Years: 1890-1915

You’ll find Knik’s transformation into a bustling commercial hub began in 1890 when gold discoveries along Cook Inlet’s Turnagain Arm triggered waves of prospectors to flood the region.

As a critical supply and transport center, Knik’s strategic location on Knik Arm made it the primary staging point for miners heading into Alaska’s interior, with steamships from Seattle bringing steady streams of fortune-seekers.

Gold Drives Economic Growth

Following a momentous gold discovery along Cook Inlet’s Turnagain Arm in the early 1890s, Knik transformed from a small Athabascan settlement into a bustling commercial hub.

The economic impact of gold mining reshaped the region as thousands of prospectors arrived seeking their fortune.

You’ll find these remarkable changes during Knik’s boom years:

- The population exploded from 46 Athabascan residents in 1880 to roughly 500 people by 1915

- Essential businesses emerged, including Orville Herning’s Knik Trading Company

- Hotels, saloons, stores, a barber shop, and even a jail were established

- The 1912 arrival of gold bullion sparked renewed mining interest

Knik’s rapid growth exemplified the transformative power of the gold rush era, as the town became the primary commercial center for upper Cook Inlet by the early 1900s.

Trade Hub Takes Shape

The economic momentum from gold discoveries propelled Knik into its role as upper Cook Inlet’s primary trading center.

You’d have found Orville Herning’s Knik Trading Company at the heart of commerce, alongside the Alaska Commercial Company and other merchants serving miners, trappers, and homesteaders.

Peak Population and Commerce

During Knik’s golden age between 1890 and 1915, this bustling trade hub reached its zenith with roughly 500 residents in town and hundreds more in the surrounding area.

Population demographics shifted dramatically from the early 1900s when just 150 Indians and 40 white people called Knik home.

You’d find a remarkable commercial infrastructure that included:

- Four hotels and three saloons for travelers and socializing

- Essential services like two doctors, two dentists, and a local newspaper

- Entertainment venues including a movie theater, pool hall, and barber shop

- Four general stores stocking supplies for miners and locals

The Place of Sweets offered tobacco, magazines, and candies, while a U.S. Commissioner’s office and jail maintained order in this thriving frontier town.

Life in a Frontier Town

Life in Knik’s bustling frontier community peaked between 1913-1916, when approximately 500 residents called this Cook Inlet settlement home.

You’d find a diverse mix of Native Dena’ina people, gold miners, farmers, and merchants all adapting to frontier challenges together. Despite harsh winters that tested everyone’s resilience, the community thrived with three doctors, two dentists, and various shops serving daily needs.

The town’s community resilience showed in how residents supported each other. You could buy fresh vegetables from local farmers who cultivated 500 acres, get your news from the Knik News, and send your children to the local school.

While law enforcement was minimal, the town remained remarkably peaceful, with residents relying on cooperation rather than formal authority.

Transportation Hub and Commercial Center

Situated at a prime location along Cook Inlet, Knik emerged as a major transportation nexus in the early 1900s, connecting Alaska’s interior with coastal shipping routes.

The transportation dynamics evolved as docks extended over mudflats to accommodate deep-draft vessels, while dog sled teams brought gold from remote mining districts.

You’ll find Knik’s commercial evolution reflected in these key developments:

- Processed 3,400 pounds of gold from the Iditarod region in 1916

- Transformed from an Alaska Commercial Company post to Knik Trading Company’s marketplace

- Supported 500 residents with hotels, saloons, stores, and entertainment venues by 1915

- Served as a crucial supply chain hub for miners, trappers, and government exploration parties

The town’s strategic position made it essential for both maritime trade and inland commerce, though challenging tides and harbor limitations persisted.

The Railroad’s Fatal Impact

While Knik thrived as a bustling hub in the early 1900s, the construction of the Alaska Railroad would ultimately seal its fate.

The rail line’s route bypassed Knik entirely, redirecting the flow of commerce and people away from the once-prosperous settlement. You’ll find that railroad accidents and safety concerns of the era only hastened the town’s decline, as travelers opted for the newer, more established routes.

The economic impact was devastating.

The railroad’s path through other areas meant that Knik’s role as a transportation center quickly diminished. What you might’ve seen in Knik’s heyday – busy docks, trading posts, and crowded streets – soon became silent reminders of a bygone era.

Like many Alaskan communities affected by changing transportation routes, Knik couldn’t survive being left off the rail line.

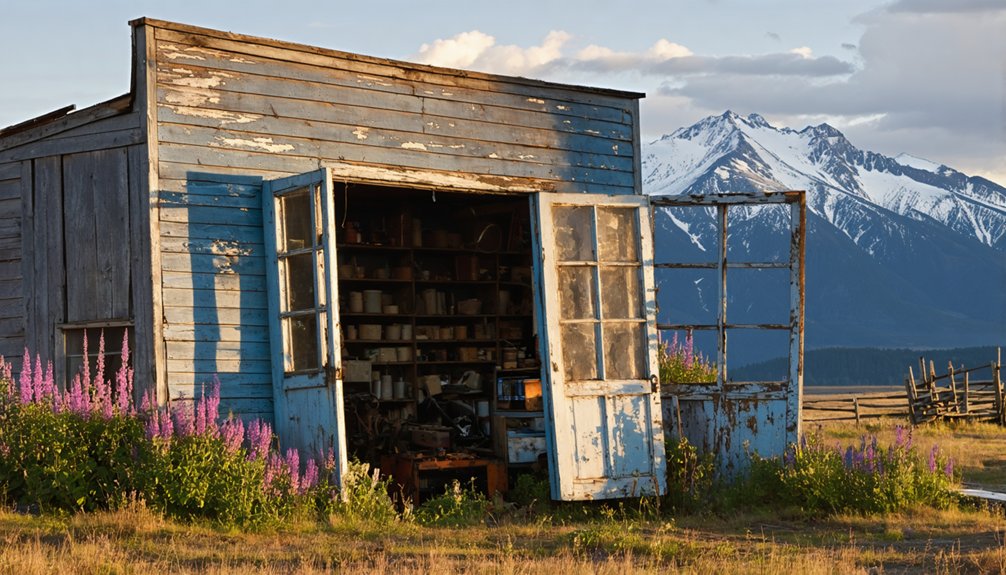

From Bustling Town to Ghost Town

At the height of its prosperity in 1915, Knik bustled with nearly 500 residents enjoying the amenities of a well-established frontier town.

You’d have found a thriving hub where Knik’s economy supported multiple hotels, stores, and entertainment venues, reflecting the dynamic spirit of Alaska’s gold rush era.

- Four hotels and three saloons served weary travelers and miners

- A movie theater, pool hall, and The Place of Sweets offered entertainment and treats

- Two doctors, two dentists, and religious services met residents’ essential needs

- Two trading posts and various shops supplied prospectors heading to the goldfields

Preserving Knik’s Legacy Today

Today, preservation efforts in Knik focus on protecting both cultural heritage and environmental resources through a thorough approach led by the Alaska Knik Tribe.

You’ll find their Natural Resources Department spearheading cultural preservation initiatives while conducting research to expand knowledge of Knik’s rich heritage. They’ve partnered with federal agencies and joined Alaska’s Green Star® program to combine environmental stewardship with pollution prevention in rural Native villages.

While few historic buildings remain in Knik, you’ll see some have been relocated to nearby Wasilla for protection.

The Matanuska-Susitna Borough’s Historic Preservation Plan carefully monitors major development projects like the Port MacKenzie Rail Extension to protect archaeological sites and traditional resources, ensuring Knik’s legacy endures despite ongoing regional growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Descendants of Knik’s Original Residents?

Like hitting the reset button, you’ll find descendant stories reveal most Native inhabitants relocated to Eklutna (“New Knik”), where they brought their chapel and historical impact lives on through tribal councils.

Are There Any Haunted Locations or Paranormal Activities Reported in Knik?

You won’t find documented ghost sightings or official paranormal investigations in Knik. While the old pool hall museum and abandoned structures might spark curiosity, there’s no verified supernatural activity in historical records.

What Was the Average Temperature and Climate in Knik’s Heyday?

You’d find Knik’s weather historically featured long cold winters below freezing and mild summers reaching about 67°F (19°C), with frequent overcast skies and moderate precipitation throughout its peak settlement years.

How Much Did Basic Supplies Cost During Knik’s Peak Trading Period?

Gold’s glitter meant steep prices at trading posts – you’d pay premium rates for basics. Sugar and coffee cost several days’ wages, while mining supplies could drain a month’s earnings.

What Wild Animals Were Commonly Encountered by Knik’s Early Settlers?

You’d regularly face moose encounters near the Knik River and bear sightings in forested areas, while mountain goats, Dall sheep, and abundant salmon filled the waters during seasonal migrations.

References

- https://www.alaska-stories.com/p/the-knik-alaska-story

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i73lBrRYWMk

- https://auntphilstrunk.com/town-called-knik/

- http://sites.rootsweb.com/~coleen/knik.html

- https://www.anchoragememories.com/wasilla-alaska.html

- https://www.kniktribe.org/alaska-knik-tribe-history

- https://www.cityofwasilla.gov/315/Wasilla-History

- https://www.mvhphotoproject.org/artifacts/knik-1

- https://www.sketchesofalaska.com/2017/04/knik-alaska-little-survives-of-early.html

- https://www.alaskahistory.org/biographies/whitney-john-d-bud/