You’ll find Leesville, Texas nestled near Sandy Creek in Gonzales County, where Newburn H. Guinn officially founded the settlement in 1874, marking its location with a prominent granite stone. Originally named Capote, then Leesburg after Guinn’s daughter Lee, postal authorities changed it to Leesville. The town peaked at 400 residents in the early 1900s before declining after its post office closed in 1907. The site’s rich frontier history holds fascinating tales of survival, conflict, and community spirit.

Key Takeaways

- Leesville, Texas was founded in 1874 and reached its peak population of 400 residents in the early 1900s.

- The closure of the post office and general store in 1907 marked the beginning of the town’s decline.

- A devastating flood in 1936 destroyed infrastructure and prompted significant population migration from the area.

- The lack of railroad connections and declining agricultural activity contributed to Leesville’s eventual abandonment.

- The population drastically decreased from 400 to 300 during the 1930s economic downturn, leading to the town’s ghost status.

The Birth of a Frontier Settlement

While early settlers had inhabited the area known as “the Sandies” since the 1830s, Leesville’s official founding came in 1874 under Newburn H. Guinn.

You’ll find the settlement’s roots near Sandy Creek, where a prominent granite stone served as a landmark for the frontier economy until its destruction in the 1870s.

The area, previously called Capote after the nearby hills, faced settlement challenges as it evolved from wilderness to civilization. Much like the coal town of Thurber, early residents relied on a company store system for basic supplies.

Originally named Leesburg after Guinn’s daughter Lee, the town had to adapt when the U.S. Postal Service required a change to Leesville, due to another Leesburg in Texas.

The land’s rich history includes holdings by Ezekiel Wimberly Cullen, a former Republic of Texas Supreme Court Justice and Congressman.

The region’s humid subtropical climate and fertile valleys made it particularly attractive for agricultural development.

Early Conflicts and Native American Relations

During the region’s early settlement, Leesville residents you’d find near Sandies Creek constantly confronted the threat of Native American raids that impacted their daily lives and farming activities.

The trading post located along Sandies Creek became a flash point in 1826 when several settlers were killed in a violent clash with local tribes, forcing the community to strengthen its defensive measures. After years of tension between settlers and tribes who held squatters rights from Spanish authorities, conflicts intensified throughout the region. Like other Texas settlements, Leesville faced raids from the Lords of the Plains as Comanche warriors dominated the territory.

You’ll find that by 1840, Leesville settlers had established regular patrols and constructed fortified positions to protect their families from ongoing raids, which continued to shape the settlement’s development throughout its early years.

Sandies Creek Trading Massacre

In the volatile 1860s, the Sandies Creek Trading Massacre marked one of Texas’ darkest frontier episodes, as elements of the 1st and 3rd Colorado Volunteer Cavalry Regiments under Colonel John Chivington launched a devastating attack on peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho villages near Leesville. The attack mirrored the tactics used during Chief Buffalo Hump’s vengeful Great Raid of 1840.

The eight-hour assault left approximately 230 Native Americans dead, including respected tribal leaders and council members. Chivington’s forces used howitzer cannons to destroy defensive trenches while committing brutal atrocities. This attack occurred on November 29, 1864, mirroring similar acts of violence against Native Americans during the period.

In the massacre aftermath, tribal relations deteriorated rapidly as the peace faction within the tribes collapsed. The Dog Soldiers and other militant groups gained prominence, rejecting further treaty negotiations.

The event shattered the traditional political structure of the Southern Cheyenne and sparked intensified resistance across the frontier, forever changing the landscape of Native American relations in Texas.

Frontier Settlement Defense Challenges

Throughout the 1830s, settlers in Leesville faced persistent defensive challenges as they established homesteads near Sandy Creek. Without a dedicated military fort nearby, you’d find these pioneers implementing their own defensive strategies against Comanche raids and criminal threats.

Similar to how the Buffalo Soldiers faced mixed attitudes after the Civil War, the isolated location forced settlers to rely on community cooperation, sharing resources and forming informal militias for protection.

You’ll note that the region’s conflicts weren’t limited to the infamous 1835 massacre of 13 Mexican and French traders. Settlers continually adapted to threats through vigilance and mutual aid.

Local ranches, like El Capote (est. 1806), served as makeshift defensive positions. From 1863 to 1883, even a single crowbar was shared among neighbors, highlighting the tight-knit nature of frontier defense and the settlers’ resourceful approach to survival. The place name disambiguation helped distinguish this Leesville settlement from others across the frontier territories.

From Leesburg to Leesville: A Name’s Evolution

You’ll find that Leesville’s name evolved from its original 1870 designation as Leesburg, chosen by developer Newburn H. Guinn to honor his daughter Lee.

In 1874, the U.S. Postal Service required a change from Leesburg to Leesville due to another Texas town already bearing the Leesburg name.

The state of Texas officially recognized Leesville in 1891, solidifying the community’s legal identity while preserving the familial connection to Guinn’s daughter.

Prior to being called Leesburg, the settlement was known as Capote, taking its name from the nearby Capote Hills.

The area’s development accelerated when land grants were issued by Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar in 1841.

Postal Service Name Change

When postal authorities rejected Newburn H. Guinn‘s attempt to name the town Leesburg around 1870, they cited an existing Texas town of the same name.

You’ll find this created a significant challenge for the community, which had operated under the name Capote when first applying for a post office in 1873.

To resolve these postal conflicts while preserving the name significance of honoring Guinn’s daughter Lee, the U.S. Postal Service implemented a practical solution in 1874.

They modified Leesburg to “Leesville,” creating a unique identity that avoided confusion with the other Texas town.

This change proved lasting – by 1885, the federal government recognized Leesville in patents, and in 1891, Texas state law officially confirmed the name that endures in historical records today.

Guinn Family Legacy

The influential Guinn family shaped Leesville’s early development through extensive land ownership and community building in East Texas. In 1868, Newburn H. Guinn began dividing land on Leesville’s west bank into town lots, establishing the foundation for commercial growth. His daughter Lee inspired the town’s original name, Leesburg.

The family’s impact extended beyond land development. Leonidas Guinn and his wife owned roughly 5,000 acres in Angelina County, stretching from Burke to Pine Valley. Their land contributions included 7.5 acres for Ryan Chapel Methodist Church and cemetery.

After Lee’s death in 1874, their daughter Nannie inherited 540 acres that became central to Burke’s development. Through marriages with other pioneer families like the Ganns, the Guinns’ legacy became deeply woven into East Texas history.

Legal Recognition Timeline

While the Guinn family’s influence shaped early land development, Leesville’s official recognition emerged through a complex series of name changes spanning several decades.

You’ll find that in 1873, the community first gained postal recognition as Capote, reflecting its connection to the nearby hills.

When Newburn H. Guinn attempted to establish a stronger community identity by renaming it Leesburg after his daughter, postal authorities rejected the proposal due to another Texas town already claiming that name.

By 1874, the compromise name “Leesville” was adopted, leading to federal acknowledgment in 1885 and state recognition in 1891.

The name’s historical significance endures today, preserved in local landmarks like the Quien Sabe Ranch signs, despite the town’s eventual decline.

Pioneer Life and Community Sharing

As pioneer families settled in Leesville during the 1860s, community sharing became essential for survival and growth.

You’d find remarkable examples of resource sharing, like the communal crowbar that served the settlement from 1863 to 1883, demonstrating the depth of community cooperation among early residents.

You’d witness neighbors helping each other with farming equipment, livestock management, and building projects. The sharing extended beyond tools to include grazing lands, agricultural knowledge, and labor exchange during harvest seasons.

While trust enabled this cooperative system, it wasn’t without challenges – incidents like John Hester’s sheep theft case and the alleged crowbar theft tested community bonds.

Still, these practices of mutual aid helped Leesville’s pioneers maintain their independence while fostering the interdependence needed for frontier survival.

Law and Order in the Wild West

Living in Leesville during the 1860s-1880s meant facing significant law enforcement challenges, as the town lacked formal policing structures common in more established regions.

Frontier towns like Leesville struggled with law and order, operating without the established police forces found in more developed areas.

You’d find yourself relying heavily on community policing and vigilante justice to maintain order. The sparse governance attracted criminals and runaways, while Comanche raids posed constant threats, particularly killing 13 traders near Sandies Creek in 1835.

When crimes occurred, you’d need to travel to the Gonzales County district court for legal proceedings, though outcomes were often uncertain due to unreliable testimonies.

Local residents shared resources and formed ad hoc committees to address thefts and disputes. In 1884, even the governor’s office became involved when John Hester received a pardon for sheep stealing – though such pardons could be revoked.

The John Hester Pardon Controversy

The 1884 pardon of John Hester by the Texas governor’s office sparked heated debates throughout Leesville’s community.

The pardon implications rippled through the small Texas town, creating deep divisions among neighbors who’d previously lived in harmony.

Legal debates filled the town hall meetings and local gatherings, reflecting the broader tensions in post-Civil War Texas about justice and mercy.

- Townspeople gathered frequently at the Leesville courthouse to discuss the controversial pardon

- The governor’s decision aligned with Texas’ policy of using pardons to manage prison populations

- Local legislative records show heated discussions during special sessions about the case

- Community leaders argued over the balance between redemption and public safety

- The controversy contributed to growing social rifts that would later affect Leesville’s decline

The Town’s Gradual Decline

While Leesville’s population thrived with nearly 400 residents during its peak years from 1904 through the 1920s, the town’s downward spiral began in 1907 with the closure of its post office and general store.

The economic decline accelerated during the 1930s as the population dropped to around 300.

You’d find the situation worsened dramatically after the devastating flood of 1936, which destroyed crucial infrastructure and prompted significant population migration to nearby communities.

The lack of railroad connections and major transportation routes left Leesville isolated while competing towns flourished with better amenities and job opportunities.

The town’s fate was sealed as local agriculture diminished and businesses relocated.

Without its fundamental services or commercial centers, Leesville couldn’t sustain itself, and by the late 20th century, it had transformed into a ghost town.

Modern Water Infrastructure Development

Despite its ghost town status, Leesville experienced a remarkable revival in 2012 with the construction of a $149 million water facility owned by Schertz-Seguin Local Government Corporation (SSLGC). This modern infrastructure development transformed the area into an essential water supply hub for the San Antonio region.

- 40-mile pipeline system draws from the Carrizo Aquifer, serving over 60,000 households

- Storage capacity reaches 11.6 million gallons with annual pumping rights of 19,363 acre-feet

- Generates consistent revenue exceeding $9.2 million yearly since 2016

- Strategically positioned between Gonzales and Guadalupe Counties for maximum efficiency

- Helps reduce San Antonio’s dependence on the Edwards Aquifer

While many Texas water systems face infrastructure challenges with aging pipes from the 1960s, Leesville’s facility stands as a demonstration of modern water management, supporting regional growth and drought resilience.

Legacy Among Texas Ghost Towns

Among Texas’s numerous ghost towns, Leesville stands out for its unique evolution from an 1874 frontier settlement to its modern role as a water infrastructure hub.

You’ll find its cultural heritage deeply rooted in the 1830s settlement near “the Sandies,” where Native American conflicts and frontier life shaped the community’s early character.

Unlike mining ghost towns or ports that died suddenly, Leesville’s economic changes occurred gradually.

While the town’s electoral participation in the 1880s showed thousands of votes, its decline mirrors many rural Texas settlements.

Today, you can trace its legacy through historical markers and the Ezekiel W. Cullen League lands, though recent challenges like the 2020 theft of a porcelain sign remind you of the ongoing struggle to preserve its history.

Frequently Asked Questions

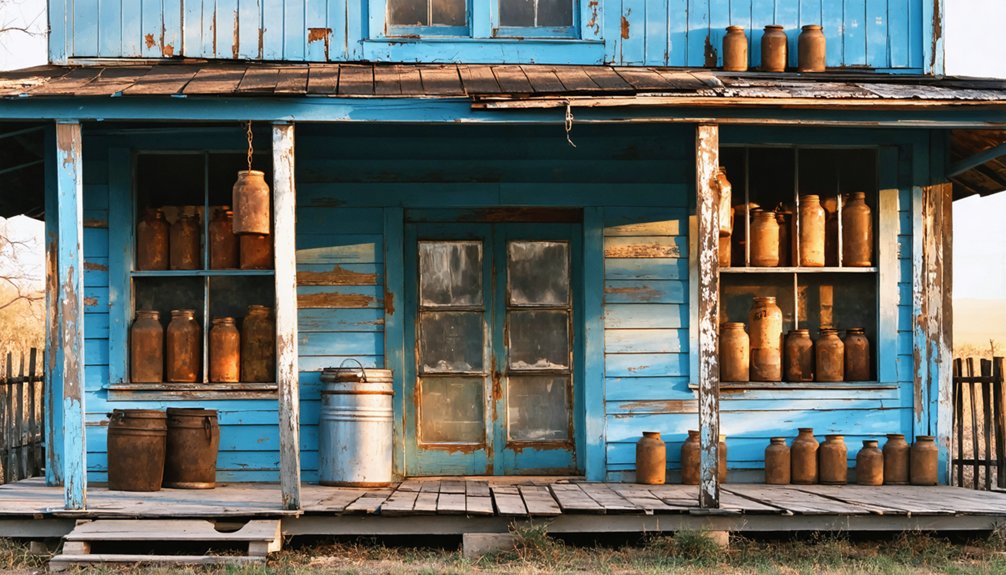

Are There Any Remaining Original Buildings Still Standing in Leesville Today?

You’ll find the Leesville School House standing as the only confirmed original architecture from the town’s early days, though preservation efforts haven’t documented other intact buildings surviving since the 1936 flood.

What Was the Highest Recorded Population of Leesville During Its Peak?

Like a prairie town at its zenith, you’ll find the highest population peaked at roughly 400 residents during 1904-1920s, marking the most significant population trends before declining to 300 in the 1930s.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Ever Visit or Live in Leesville?

You won’t find records of famous visitors in Leesville’s history, though Ezekiel W. Cullen had land holdings there. The town’s historical significance stems from local settlers rather than celebrity connections.

What Industries or Businesses Sustained Leesville’s Economy Before Its Decline?

Like mighty oaks that once stood tall, you’d find hardwood logging dominated the economy, alongside agricultural practices like grain farming and cattle ranching. Local businesses served travelers passing through on the highway shortcut.

Are There Any Annual Events or Historical Commemorations Held in Leesville?

You’ll find the annual Fall Festival in early November at the Community Center, plus the Country Fair featuring Happy Quilters’ auctions. While there aren’t historical reenactments, locals share folklore about Sandies Creek’s 1835 encounters.

References

- https://mix931fm.com/cherokee-county-ghost-towns/

- https://texascooppower.com/south-texas-lost-ghost-town-of-linnville/

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Leesville

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leesville

- https://texashighways.com/travel-news/four-texas-ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.texasescapes.com/CentralTexasTownsSouth/Leesville-Texas.htm

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/leesville-tx

- https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Leesville

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Sandies_Creek