You’ll find Myers City tucked away in South Dakota’s Black Hills, established during the 1870s gold rush following Custer’s expedition. The town grew rapidly around the Alta Mine, supporting about 150 residents with its Alta Lodi Mill processing 0.410 ounces of gold per ton. After the mill’s relocation to Lookout, Myers City declined into abandonment, leaving behind deteriorating structures and mining remnants. Its story mirrors countless boom-and-bust mining communities that shaped the American West.

Key Takeaways

- Myers City emerged during the Black Hills Gold Rush in the 1870s, established near the Alta Mine as a bustling mining community.

- The town’s population peaked at 150 residents, primarily consisting of miners and their families working at Alta Lodi Mining Company.

- Economic decline began when the Alta Lodi Mill was dismantled and relocated, leading to the town’s eventual abandonment.

- Today, the ghost town features deteriorating structures and mining remnants, with no formal tours but self-guided exploration possible.

- The site stands as a testament to the boom-and-bust cycle of mining communities in the Black Hills region.

The Origins of a Black Hills Mining Town

While the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had established the Black Hills as Lakota Sioux territory, General George Armstrong Custer‘s 1874 expedition changed everything by discovering gold near present-day Custer, SD. The discovery sparked an unstoppable Black Hills Gold Rush that began in 1875, bringing waves of prospectors into the region, despite ongoing Lakota conflicts and military resistance to settlement.

Among the many mining camps that emerged during this chaotic period was Myers City, also known as Altamine.

You’ll find its origins tied to the nearby Alta Mine, established during the prosperous period after the 1875 gold discoveries. Like other Black Hills settlements of the era, the town sprang up hastily, with minimal planning and basic structures to support the miners who’d ventured into this contested territory seeking their fortunes. The miners’ dreams of striking it rich mirrored the success of the Homestake Mine that had become the region’s largest gold producer.

Mining Operations and Economic Growth

You’ll find the Alta Lodi Mill‘s operations were central to Myers City’s early development, processing ore from the surrounding mines using stamp mills and mercury amalgamation techniques.

The mill’s introduction of industrial-scale processing methods marked a significant shift from basic placer mining to more sophisticated hard-rock extraction. Similar to major operations like Homestake, the mill processed approximately 0.410 ounces of gold from each ton of ore.

Workers hauled ore in hand-loaded buckets and carts to the mill, where the crushing of gold-bearing quartz and subsequent amalgamation process helped establish Myers City as a serious mining operation in the Black Hills. Like many similar sites in South Dakota, Myers City eventually became a ghost town, reflecting the boom-and-bust cycle of mining communities.

Alta Lodi Mill Operations

The Alta Lodi Mining Company‘s 40-stamp mill stood as Myers City’s industrial centerpiece during the late 19th century, processing ore from nearby mines and providing essential employment for the town’s residents.

Despite its impressive size and mill efficiency, you’d find that the facility faced persistent operational challenges, primarily due to insufficient ore supply to maintain continuous production. Like many mining operations of its era, the company maintained detailed legal records through local title companies to document its mineral rights and property holdings.

The mill’s operations eventually ceased when the structure was dismantled and relocated to the nearby town of Lookout.

Early Mine Development Phase

During the late 19th century, Myers City’s mining operations expanded rapidly through a combination of technological innovation and strategic infrastructure development. Early miners, led by pioneers like John Myers, established critical transportation routes that connected to nearby logistics hubs like Rochford. Similar to the 1877 fire that devastated nearby Gayville, disasters posed constant threats to mining operations.

The Homestake Mining Company’s railroad system proved essential for moving ore and supplies throughout the region. Safety measures included requiring all miners to wear protective helmets and specialized equipment.

Underground operations grew increasingly sophisticated as mining companies installed compressed air locomotives and developed extensive ventilation systems that circulated 500,000 cubic feet of fresh air per minute.

By 1906, major shafts including Ellison, B&M, Golden Star, and Golden Prospect had yielded approximately 1.5 million tons of ore.

The introduction of cyanidization technology dramatically improved gold recovery rates to 94%, far surpassing older mercury-amalgamation methods.

Daily Life in Myers City

If you’d lived in Myers City during its heyday, you’d have resided in a basic wooden home alongside roughly 150 other residents, mostly miners and their families.

Your daily schedule would’ve revolved around the demanding shifts at the Alta Lodi Mining Company‘s 40-stamp mill or in the mines themselves, where long hours and hazardous conditions were the norm.

After work, you might’ve participated in occasional community gatherings that helped foster a sense of camaraderie among the town’s inhabitants, though leisure time was limited by the harsh realities of frontier mining life. Similar to the Longhorn Saloon in Scenic, the local tavern had oil barrel stools for patrons. Like many towns in South Dakota, the community had access to a grain elevator that served the local agricultural needs.

Living Conditions and Housing

Life in Myers City revolved around hastily constructed wooden frame houses that dotted the landscape near mining operations.

You’d find these simple dwellings built from locally sourced Black Hills timber, perched atop stone foundations that still peek through the earth today. Housing materials were basic but functional, reflecting the town’s rapid growth during the mining boom.

Living amenities were sparse – you wouldn’t find indoor plumbing or running water in most homes. Instead, you’d rely on outhouses, wood stoves for heat, and kerosene lamps for light.

Food storage meant digging root cellars or maintaining simple pantries. Your home’s location near mine shafts and ore processing facilities exposed you to constant noise, dust, and chemical pollutants, while unpaved streets turned dusty in summer and muddy in winter.

Work and Social Activities

While men toiled deep within the mines of Myers City, the town’s daily rhythm revolved entirely around the Alta Lodi Mining Company‘s schedules and demands.

You’d find most able-bodied men working seasonal employment shifts in the mines or supplementary logging operations, while skilled craftsmen and merchants provided essential support services.

Life wasn’t all work, though. Community gatherings brought residents together in saloons, boarding houses, and even caves for dances and musical performances.

You could catch locals sharing stories over drinks, hunting in the Black Hills, or fishing nearby streams.

Women managed households and fostered mutual support networks vital for survival, while children pitched in with family duties.

Despite the harsh realities of mining life, you’d witness a tight-knit community where neighbors helped each other through accidents, emergencies, and daily challenges.

The Decline and Abandonment

Once Myers City’s 40-stamp mill fell into disuse, the town’s rapid decline became inevitable. The economic impact rippled through the community as small-scale mining operations between 1892 and 1936 couldn’t sustain the population of 150 residents.

Without the railroad’s crucial connection to larger markets, you’d have seen the town’s isolation intensify, making it harder for businesses to survive or new settlers to arrive.

Community factors accelerated the abandonment as families departed, forcing local services and shops to close their doors.

You’ll find that competition from neighboring mining operations drew away essential resources and labor, while the town’s inability to diversify beyond mining left it vulnerable.

The Great Depression dealt another blow, and Myers City couldn’t recover as buildings deteriorated and mines fell silent.

Exploring the Ghost Town Today

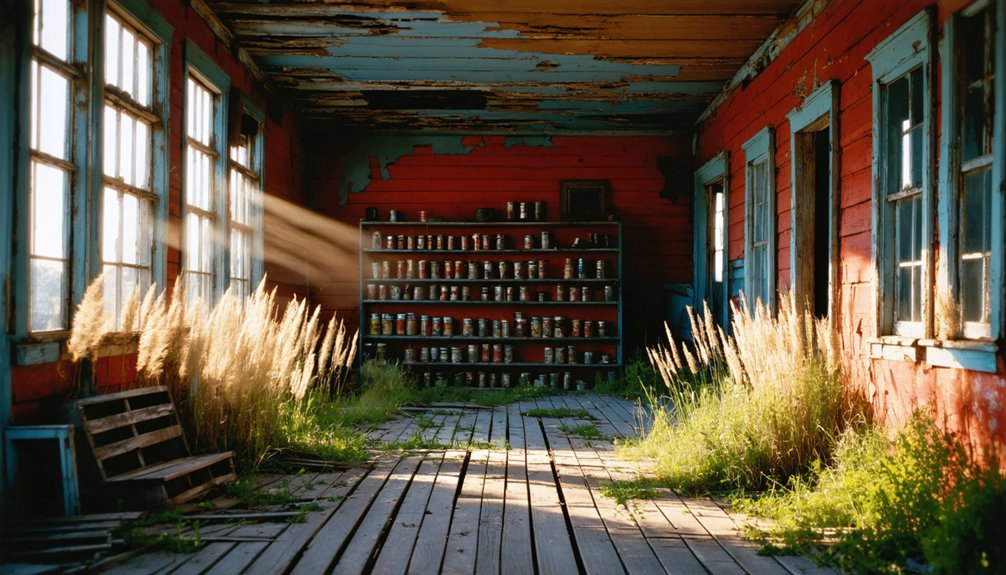

Today’s visitors to Myers City encounter a haunting tableau of deteriorating structures and mining remnants.

You’ll find yourself maneuvering through a landscape where ghost town aesthetics are on full display – from roofless buildings to weathered facades that tell tales of the past.

As you explore ghost towns in South Dakota, each abandoned structure offers a glimpse into a time long gone. The eerie silence is punctuated only by the whispers of the wind, inviting you to imagine the lives once lived within these now desolate spaces. Be prepared to encounter remnants of history that echo the resilience and struggles of the communities that once thrived here.

The exploration challenges you’ll face include unstable structures and uneven terrain, so you’ll need to exercise caution while discovering the site’s historical treasures.

- No formal tours are available, so you’re free to explore at your own pace

- Bring your camera to capture the haunting beauty of abandoned buildings

- Watch for hazards like deteriorating floors and unstable walls

- Access may be restricted due to private ownership

- Pack essentials as there aren’t any visitor facilities or amenities nearby

Historical Significance in Black Hills Mining Heritage

As a cornerstone of Black Hills mining heritage, Myers City represents the region’s transformative gold rush era that began in the late 1870s.

Like many Black Hills settlements, it emerged during a time when mining techniques were rapidly evolving, from basic prospecting to sophisticated deep mining operations utilizing winzes and mechanized equipment.

You’ll find that Myers City’s story mirrors the broader cultural legacy of Black Hills mining towns, where boom-and-bust cycles shaped community life.

The town’s development coincided with significant technological advancements, including the revolutionary cyanidization process that improved gold recovery rates.

Today, this ghost town stands as a monument to the economic volatility that characterized mining communities, while preserving an important chapter in the region’s rich mining heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Documented Accidents or Deaths From the Myers City Mines?

You won’t find conclusive historical records of mining accidents in Myers City, as documentation of this lesser-known location’s mining activities and potential casualties remains particularly sparse or nonexistent.

What Happened to the Original Residents After They Left Myers City?

Like scattered seeds in the wind, you’ll find that most residents dispersed across the Black Hills region. Life after Myersville led to migration patterns showing movement toward larger mining towns and established communities.

Were There Any Schools or Churches Established in Myers City?

You won’t find evidence of formal schools or churches in historical records. While the mining town’s peak population of 150 could’ve supported these institutions, there’s no documentation confirming their establishment.

Did Any Famous or Notorious People Ever Visit Myers City?

You won’t find any famous visitors or notorious figures in historical records – there’s no evidence anyone of significant reputation ever visited this remote mining settlement during its brief existence.

Has There Been Any Effort to Preserve or Protect the Site?

You’ll find limited site preservation efforts, mostly through historical documentation and archival records. Private property status restricts formal heritage conservation programs, though local historical societies help maintain awareness through informal measures.

References

- https://www.sdpb.org/rural-life-and-history/2023-08-21/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins

- https://www.sdhspress.com/journal/south-dakota-history-2-2/some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins/vol-02-no-2-some-black-hills-ghost-towns-and-their-origins.pdf

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/345016075.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0WNYsFLSLA

- https://www.southdakotamagazine.com/scenic

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_South_Dakota

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/sd/myersville.html

- https://kxrb.com/watch-out-for-michael-myers-hiding-in-small-south-dakota-town/

- https://www.deadwood.com/history/history-timeline/

- https://history.sd.gov/archives/docs/Brennan.pdf