Negro Flat was an African American mining settlement established around 1850 along California’s Salmon River in Siskiyou County. You’ll find it was part of a network including Negro Bar, Negro Hill, and Little Negro Hill. At its peak in the 1850s, the camp housed about 400 diverse residents who panned for gold using basic techniques. Today, only mining terraces and tailing piles remain, with nature reclaiming this forgotten piece of multicultural Gold Rush history.

Key Takeaways

- Negro Flat was established around 1850 as part of a network of African American mining camps in Siskiyou County, California.

- The ghost town reached a population of 400-1,200 residents during the Gold Rush with a diverse multicultural community.

- Mining activities depleted by mid-1850s, causing decline as miners abandoned claims for farming or richer strikes elsewhere.

- Few physical structures remain today, with the landscape showing only mining terraces, tailing piles, and modified riverbeds.

- Located at 41°14′31″N 123°16′51″W along the Salmon River, the site requires forest service road access with minimal tourist infrastructure.

The Gold Rush Origins of Negro Flat (1850)

Four distinct African American mining camps emerged in California during the Gold Rush, with Negro Flat established around 1850 as part of this network that included Negro Bar, Negro Hill, and Little Negro Hill.

Massachusetts Flat was also connected to this community of Black miners.

These settlements represented remarkable African American resilience in a hostile environment.

Amid prejudice and danger, Black mining camps stood as bold testaments to African American determination and community building.

While California entered the Union as a free state in 1850, discrimination remained rampant and fugitive slave laws threatened even free Blacks.

The small population—only 962 African Americans in California by 1850—formed mutual aid societies for protection and support.

Most miners came from northern states like New York and Pennsylvania, seeking economic opportunity despite widespread prejudice.

Their organized presence in the gold fields created rare spaces of relative autonomy where Black miners could work collectively and build community.

African American miners often worked alongside Chinese and Portuguese miners, demonstrating collaborative relationships that developed among various ethnic groups in these diverse mining communities.

Despite their small numbers, Black entrepreneurs in these mining communities established successful businesses such as hotels, laundries, and restaurants to serve the growing population.

Geographic Location and Natural Setting

While African Americans built resilient communities during the Gold Rush, the physical landscape they inhabited played a significant role in shaping their experiences.

Negro Flat sits in Siskiyou County, California at 41°14′31″N 123°16′51″W, nestled along the Salmon River, a tributary of the Klamath.

You’ll find the settlement surrounded by rugged, mountainous terrain with elevations ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 feet. Dense forests of Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, and oak trees dominate the landscape, home to black-tailed deer, bears, and mountain lions.

The geographic features created both opportunities and challenges, with the Salmon River providing essential natural resources for mining operations while also causing seasonal flooding. Like many California ghost towns established in the mid-1800s, Negro Flat experienced periods of prosperity followed by eventual decline and abandonment.

The remote location in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion meant limited access, creating a relatively isolated community within these temperate but demanding surroundings. According to USGS data, Negro Flat was a site where gold mining operations took place at an elevation of approximately 2,500 feet.

Multicultural Mining Community Composition

At Negro Flat, you’ll find a diverse settlement pioneered by Black miners who established claims as early as 1849, often forming mutual aid societies for protection amid racial tensions.

These African American entrepreneurs didn’t limit themselves to mining, as many operated successful hotels, laundries, and restaurants that supported the growing multicultural population.

Despite legal restrictions and occasional conflicts, the mining community featured remarkable cross-cultural cooperation, with Black, Chinese, Mexican, Portuguese, and Native American miners working neighboring claims and sometimes sharing operations in an economic ecosystem that allowed some miners like Samuel W. Pearsall to accumulate substantial wealth.

The community thrived with a population of 1,000 to 1,200 inhabitants by 1853, representing multiple races and cultures.

The mining operations in the region experienced typical boom and bust cycles throughout the 1850s and 1860s, similar to nearby camps like Chee Chee Flat which reached peak production during the early 1860s.

African American Pioneers

The California Gold Rush of 1849 attracted a diverse array of fortune seekers, including significant numbers of African American pioneers who established settlements throughout the gold country.

You’ll find their pioneering spirit evident in communities like Negro Bar, Negro Hill, and Negro Flat, which were initially founded by Black miners seeking their fortunes.

These African American contributions extended beyond simple prospecting. Some miners, like Samuel W. Pearsall, amassed considerable wealth—his Negro Hill claim yielded $80,000 in just four months.

Frederick Coleman’s gold discovery in San Diego County sparked an entire regional rush.

Black miners often worked alongside Chinese, Portuguese, and white miners in integrated settlements, forming mutual aid societies for protection and economic support.

Despite facing legal discrimination that restricted court testimony and education, these resilient communities adapted, establishing businesses and mining companies that shaped California’s multicultural frontier. Churches like St. Andrews AME Church served as central institutions for community formation and support among African Americans in mining towns. Organized Black mining companies like the Rare Ripe Gold and Silver Mining Company demonstrated the entrepreneurial success possible despite systemic barriers.

Cross-Cultural Work Relations

Negro Flat’s vibrant multicultural composition created a unique mining community where African-American, Caucasian, Chinese, and Portuguese miners worked together in integrated settlements throughout the 1850s.

You’d find these diverse workers operating placer mining claims side by side across the Sierra foothills.

Labor integration was particularly evident at Little Negro Hill, which attracted various ethnic groups to work adjacent claims. By 1855, approximately 400 people lived in the Negro Hill area, sustaining their operations through cultural collaboration.

Workers shared responsibilities and resources, including water ditches serving multiple camps like Growler’s Flat, Chile Hill, and Long Bar.

Despite legal barriers preventing Black miners from testifying against whites in court and occasional tensions, the community maintained peaceful coexistence most of the time, developing shared commercial centers and community establishments that served all miners regardless of background.

Diverse Entrepreneurial Activity

While mining formed the economic backbone of Negro Flat, diverse entrepreneurial ventures flourished throughout this multicultural settlement, creating a self-sustaining community beyond mere resource extraction.

You’d find Black-owned stores and boarding houses serving miners of all backgrounds, providing essential goods and lodging despite the significant legal barriers African Americans faced. The entrepreneurial spirit extended to hotels, laundries, and restaurants established by Black residents who recognized opportunities to serve the camp’s growing population of 400 diverse residents.

These businesses weren’t isolated endeavors. Complementing them was a Methodist church that fostered community cohesion among the African-American, Caucasian, Chinese, and Portuguese miners. Similar to Saint Andrews A.M.E. Church in Sacramento, these religious institutions often served as meeting sites for community organization and mutual support.

This community resilience manifested in mutual aid associations and organized mining companies like the “first class” Rare Ripe Gold and Silver Mining Company, demonstrating remarkable resourcefulness in an era of adversity.

Daily Life in a Booming Mining Camp

As dawn broke over the rugged terrain of Negro Flat, miners emerged from their tents and hastily constructed cabins to begin another grueling day of gold seeking.

You’d start work immediately, using mining techniques like panning and sluicing in the frigid river waters until dusk fell. Working in small groups, you’d manage water through elaborate ditch systems to reach promising gravel bars.

Your diet consisted mainly of beans, bacon, and coffee, occasionally supplemented by hunting or small garden plots.

A miner’s sustenance: simple fare of beans, bacon and coffee, with wild game or garden vegetables when fortune allowed.

Despite racial diversity, daily life fostered community across cultural lines. After exhausting shifts, social gatherings centered around communal meals and informal meetings where stories were shared.

The camp’s diverse population—Black, white, Chinese, and Portuguese miners—generally coexisted peacefully, forming mutual aid associations for protection and support.

Economic Rise and Peak Production Years

The economic foundation of Negro Flat took shape rapidly after initial gold discoveries during the California gold rush between 1848-1855. Situated at 2,500 feet elevation in El Dorado County, miners quickly established placer operations to extract gold from surface deposits and stream gravels.

During the early 1860s, Negro Flat reached its peak production years with numerous claims filed throughout the surrounding Mountain Ranch District. The economic impact remained modest compared to major operations like the Kentucky Ridge Mine or Washington Mine, which produced over half a million dollars during their peak years. Similar to other mining towns, Negro Flat saw an influx of diverse prospectors including forty-niners who arrived during the height of the gold rush.

Miners employed basic mining techniques including water diversion systems to enhance recovery efficiency before shallow workings depleted. As surface deposits played out, many prospectors relocated to richer strikes, though intermittent recovery attempts continued through hydraulic mining until the 1930s.

Administrative Changes Through the Decades

Negro Flat’s administrative framework underwent significant transformations throughout its existence, beginning with its original placement in Trinity County before boundary adjustments reassigned it to Siskiyou County in the early 1850s.

This jurisdictional shift affected how miners recorded claims and sought legal recourse for disputes.

California’s 1849 statehood accelerated the administrative evolution from informal governance to structured legal institutions.

Despite constitutional protections against slavery, you’d have witnessed how discriminatory practices persisted in local administration, with courts often ruling against Black miners’ interests.

As gold deposits diminished in the 1860s, administrative attention waned accordingly.

Counties gradually reclassified thriving settlements as unincorporated lands.

The jurisdictional impacts of these changes left Negro Flat with diminishing infrastructure investment, contributing to its eventual ghost town status.

Social Challenges and Racial Relations

While California promised opportunity for gold seekers of all backgrounds during the 1849 Gold Rush, Black miners at Negro Flat faced a harsh reality of systematic discrimination that shaped their daily existence.

You’d have witnessed how California’s 1854 Practice Act barred Black residents from testifying against white people in court, leaving miners vulnerable to claim-jumping without legal recourse.

The racial dynamics at Negro Flat reflected broader patterns throughout gold country, where Black miners relied on physical strength and community solidarity for protection.

Despite hostility, early Black Californians organized resistance through groups like the Franchise League and participated in Conventions of Colored Citizens.

This social activism challenged discriminatory laws and segregation practices that limited economic mobility and confined Black populations to specific neighborhoods, laying groundwork for future civil rights movements.

The Gradual Decline of Mining Operations

You’d have witnessed Negro Flat’s gold mining operations fade rapidly in the mid-1850s as lucrative placer deposits depleted, transforming a vibrant economic boom into a struggle against rising extraction costs and diminishing returns.

The environmental toll became increasingly apparent through eroded hillsides, silted streams, and deforestation—consequences of hydraulic mining and intensive resource extraction that permanently altered the landscape.

Economic Boom Fades

The abundant gold deposits that fueled California’s initial rush couldn’t last forever, and by the 1860s, the once-productive placer mines around Negro Flat began showing unmistakable signs of depletion.

What had yielded impressive profits during the 1850s quickly exhausted as miners stripped river bottoms of accessible gold.

You would’ve witnessed the multicultural heritage of Negro Flat—with its African-American, Chinese, Portuguese, and Caucasian miners—gradually disintegrate as the community of 400 scattered.

Mining technology that once served independent prospectors proved inadequate as operations shifted to deeper quartz mining requiring substantial capital investment.

Environmental Toll Revealed

As mining operations gradually declined in Negro Flat during the 1860s, devastating environmental impacts became increasingly apparent. You could witness the scarred landscape where hydraulic mining had carved deep wounds, leaving behind mountains of sterile tailings and debris exceeding 70 million cubic yards.

The region’s waterways bore the brunt of mining pollution. An estimated 10 million pounds of mercury contaminated the Sierra Nevada, transforming into methylmercury that poisoned aquatic food chains. Groundwater pumping depleted wells while contaminating others with heavy metals like iron and manganese.

The environmental toll extended to the forests, stripped bare for timber and fuel, increasing erosion and destroying wildlife habitat.

These combined impacts created a toxic legacy that would linger for generations, turning once-pristine wilderness into a damaged landscape requiring extensive restoration efforts.

Community Exodus Pattern

While abundant gold fields initially drew thousands to Negro Flat during the late 1840s, miners began noticing diminishing returns by the mid-1850s. The once-profitable claims became increasingly difficult to work, with excessive water seepage in underground leads requiring extensive drainage efforts.

You’d have witnessed a clear community migration as miners abandoned their claims. White miners shifted to farming while African Americans, who initially found success at Negro Hill, moved toward Northern California towns or British Columbia gold fields. Chinese miners eventually dominated the remaining operations.

The shift to hydraulic and tunnel mining demanded significant capital investment that small-scale miners couldn’t afford. With economic opportunities dwindling, mining towns experienced steady population decline.

Water costs rose, strikes erupted, and bankruptcies mounted. Eventually, these once-bustling communities were abandoned, with some physical traces later erased by the creation of Folsom Lake.

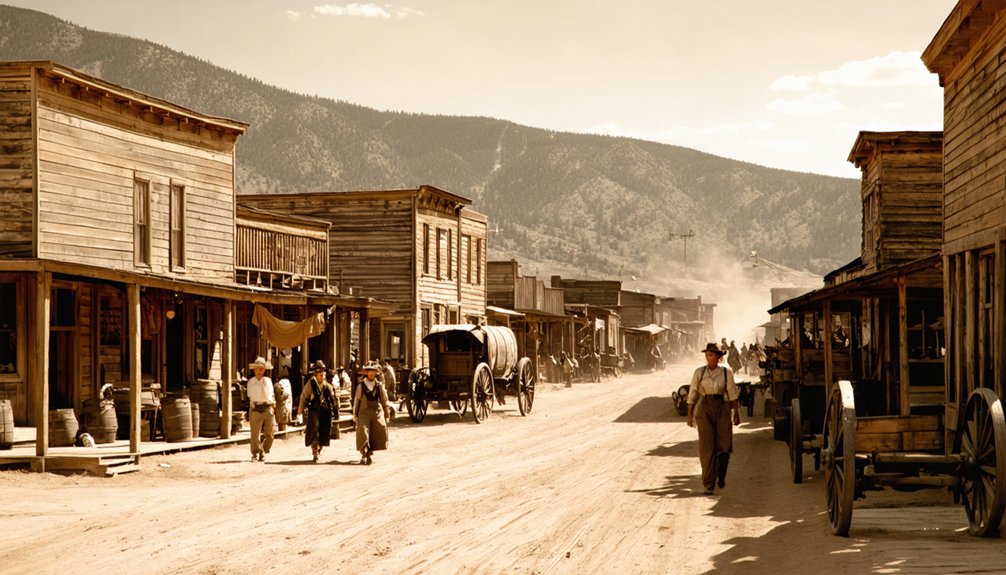

What Remains Today: Visiting the Ghost Town Site

Visiting Negro Flat today presents you with a landscape that tells its story through absence rather than presence. The former mining camp offers few standing structures, as nature has reclaimed what miners abandoned in the 1860s after gold deposits ran dry.

You’ll find ghost town remnants primarily in the form of terrain alterations—mining terraces, tailing piles, and modified riverbeds that speak to its placer mining past.

The site isn’t on typical tourist routes, requiring travel on forest service roads without dedicated facilities. You’ll need to bring supplies and navigation tools for this remote location.

Your visitor experience will be one of historical detective work, identifying sluice cuts and gravel piles rather than buildings. No interpretive signs exist to guide you—just the scarred landscape that whispers stories of California’s Gold Rush era.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the African American Miners After the Town’s Decline?

After Negro Flat’s decline, you’d see African American miners relocating to nearby gold fields, forming mutual aid networks, starting businesses, and even migrating to Canada—preserving their mining opportunities and African American legacy despite discrimination.

Were Any Notable Gold Discoveries Made by Specific Residents?

You’ll find no specific records of notable discoveries by individual African American miners at Negro Bar, though their pioneering mining techniques were essential to early gold rush success.

Did Any Descendants of Negro Flat Miners Remain in Siskiyou County?

While descendant research indicates many miners left when placer mining declined, local genealogy hasn’t conclusively documented specific Negro Flat descendants who remained in Siskiyou County through the modern era.

What Items or Artifacts Have Been Recovered From the Site?

You’re drawing a blank slate regarding artifacts analysis from this site. No official documentation details recovered items of historical significance. You’d need to consult county archives or California historical societies for accurate information.

How Did the Community Name “Negro Flat” Originate?

You’ll find Negro Flat was named during the Gold Rush when African American miners established settlements there. The name reflects historical context of 19th-century racial identification and holds cultural significance in California’s diverse mining heritage.

References

- https://www.sfgate.com/travel/article/eagle-mountain-california-ghost-town-18096768.php

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Negro_Flat

- https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/hs/im/negrohill.asp

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://westernmininghistory.com/map/

- https://www.discourseblog.com/p/a-visit-to-the-california-town-founded

- https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/c7700a3ac7b24f89a972749a711b6122

- https://thevelvetrocket.com/2012/01/03/california-ghost-towns-potosi-and-the-winkeye-mine/

- https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/african-americans-gold-rush

- https://www.libertarianism.org/articles/black-49ers