You’ll find Ochoa nestled along Alamito Creek in Presidio County, Texas, where John Davis established a farming settlement in 1870. This once-vibrant community thrived on cotton production and innovative irrigation techniques, supporting 200-300 residents at its peak. Environmental challenges, including devastating floods and droughts between 1940-1960, coupled with the railroad’s bypass, led to Ochoa’s decline. Today, weathered adobe buildings and empty storefronts stand as silent witnesses to this remarkable chapter in Texas frontier history.

Key Takeaways

- Ochoa was established in 1870 along Alamito Creek in Presidio County, Texas, as a farming settlement that later became a ghost town.

- The town’s decline began when the railroad bypassed it, leading to business migration and significant population loss by 1930.

- Severe environmental challenges, including floods and droughts between 1940-1960, devastated farming operations and accelerated the town’s abandonment.

- The population dropped from a peak of over 200 residents to fewer than 100 by 1930, with mostly elderly citizens remaining.

- Empty storefronts and weathered buildings now preserve fragments of Ochoa’s history as local organizations work on preservation efforts.

The Birth of a Farming Settlement

While frontier settlements often emerged spontaneously, Ochoa’s birth in 1870 followed a deliberate pattern of agricultural development along Alamito Creek in Presidio County, Texas.

You’ll find that John Davis’s settlement strategies proved successful as he established the community with several Mexican-descent families who worked his land.

The settlement’s prime location along the Chihuahua Trail wasn’t just coincidence – it provided crucial trade connections while irrigation techniques transformed the arid landscape into productive farmland.

Davis constructed a substantial adobe home with defensive features, recognizing the realities of frontier life and potential Indian raids.

The early community centered around essential structures including a chapel for visiting priests, reflecting the Catholic heritage of many settlers. Like nearby Camp Holland site, the structures were built with stone and wood to withstand the harsh frontier conditions.

These foundations would shape Ochoa’s development as a frontier farming outpost. Under the direction of Esteban Ochoa, irrigation projects in 1917 significantly improved the agricultural potential of the land.

Life Along the River Banks

Building upon their initial settlement success, Ochoa’s residents developed a deep connection to Alamito Creek’s rhythms and resources.

You’ll find that the settlers quickly learned to harness the creek’s potential while respecting its unpredictable nature. They constructed elevated homes and implemented basic flood management techniques to protect their properties from seasonal swells.

Like the residents of Hagerman who faced the rising waters of Lake Texoma, the community had to deal with water displacement issues.

The creek’s riverine biodiversity provided residents with abundant fishing opportunities and supported their agricultural endeavors. Similar to the residents of Old Bluffton, the community had to adapt to changing water conditions that impacted their way of life.

You’d have seen farmers adapting their planting schedules to the creek’s natural cycles, growing crops that could withstand periodic flooding.

Despite challenges from water quality issues and occasional flooding, the community thrived by diversifying their economic activities. They established small-scale tourism ventures and maintained traditional farming practices, ensuring their settlement’s sustainability through careful water resource management.

Agricultural Prosperity and Community Growth

As Ochoa entered its agricultural heyday, cotton emerged as the driving force behind the town’s early prosperity. You’d find the landscape dotted with commissaries where locals traded company currency, while a bustling train depot facilitated the export of cotton and other goods to distant markets.

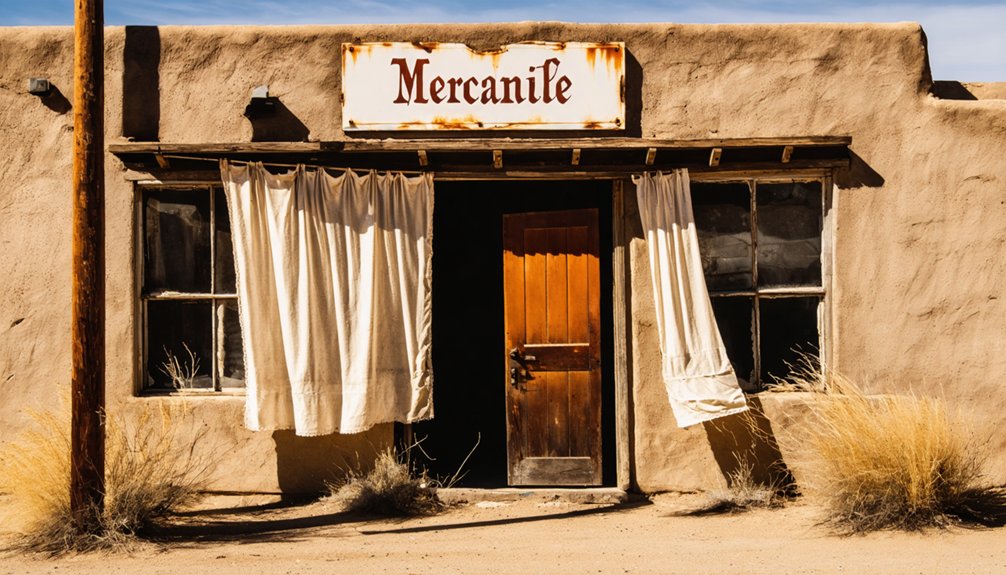

Beyond cotton fields, you’ll discover Ochoa’s remarkable crop diversification efforts and a thriving timber industry that shaped the community. Local sawmills provided essential building materials and employment, while supporting infrastructure included processing facilities like brick factories and shingle mills. Much like Manning’s Carter-Kelly Lumber Co. and other early Texas lumber towns, Ochoa developed a network of mercantile stores that served the growing population.

The town’s growth brought schools, churches, and distinctive painted homes for mill managers, creating a vibrant social hierarchy. The agricultural boom attracted various businesses that served the farming community, making Ochoa a self-sufficient hub where timber and agriculture coexisted in profitable harmony.

The People Behind Ochoa’s Story

In Ochoa’s closely-knit community, you’ll find the Russell, Vasquez, and Mata families working side by side in cotton fields and sharing resources through strong kinship networks.

You’d see these hardworking agricultural families gathering regularly for celebrations featuring music, dancing, and horse racing, maintaining their rich Hispanic cultural traditions. Like the town of Lobo, the community relied heavily on cotton farming operations until drought conditions made agriculture unsustainable.

You can trace how these early settlers’ daily routines revolved around farming staple crops while building lasting social bonds through the Vasquez family store and community gatherings. Similar to Linnville’s early days, the town served as a vital trading post for surrounding areas.

Family Life and Community

Life in Ochoa revolved around tight-knit family bonds and mutual support networks that helped residents weather the challenges of their isolated location. You’d find family gatherings were frequent events that strengthened community ties, while neighborly support became essential for survival in this remote Texas settlement. Similar to towns like Tascosa, life here was marked by a mix of law-abiding citizens and outlaws.

During tough times, residents would pool their resources and help each other with agricultural work and daily challenges. Like the residents of Silver’s ranching community, they developed strong bonds through shared work and hardships.

The local school served as a central hub for social activities, where families would come together for events and celebrations. Church meetings and civic organizations provided additional opportunities for connection.

Despite the hardships of isolation and environmental challenges, you’d discover a resilient community spirit that valued self-sufficiency and cooperation, creating a unique cultural identity that defined Ochoa’s character.

Early Settlers’ Daily Routines

The daily rhythms of Ochoa’s early settlers centered around agricultural pursuits and survival in the challenging Texas terrain.

You’d find their settler routines revolving around tending to peach orchards and managing livestock on the open range. Daily chores included the critical task of hauling water from Alamito Creek for both household needs and irrigation.

Life wasn’t easy – you’d to stay vigilant against potential Indian attacks while maintaining adobe structures and working the land. Settlers often shared labor with neighbors, whether it was constructing buildings or helping with harvests.

Trade along the Chihuahua Trail brought opportunities to sell produce to passing travelers and nearby towns like Fort Stockton. The close-knit community relied on each other’s skills and resources, making self-sufficiency possible despite their remote location.

Agricultural Workers’ Social Networks

While agricultural workers in Ochoa faced numerous challenges, they built powerful social networks that transformed their community. These social connections, often spanning across multiple states like Texas, North Dakota, and Minnesota, created resilient support systems that helped workers navigate difficult conditions and preserve their cultural heritage.

Key aspects of these community support networks included:

- Community-based organizations that provided advocacy and resources for migrant families

- Family-centered support systems that shared limited resources and helped members survive

- Cross-state communication networks that connected workers with employment opportunities

Through these networks, workers established leadership roles, fought for better conditions, and maintained strong cultural ties.

Organizations like the Nebraska Association of Farmworkers provided frameworks for advocacy while fostering collaboration between different groups to create lasting change.

Economic Changes and Population Shifts

During Ochoa’s early years as an agricultural hub in South Texas, the town’s population flourished with 200-300 residents who established a vibrant farming community.

You’d have found a bustling economy centered on cotton and livestock, complete with a general store, school, and church.

The most significant economic shifts began when the railroad bypassed Ochoa in favor of neighboring towns.

This critical decision triggered a devastating chain reaction – businesses lost their competitive edge, and trade migrated to rail-connected areas.

The population decline accelerated as young families sought better opportunities elsewhere.

By 1930, you’d have counted fewer than 100 residents, mostly elderly citizens who couldn’t or wouldn’t relocate.

The Great Depression and Dust Bowl years only hastened Ochoa’s transformation into a ghost town.

Environmental Challenges and Agricultural Impact

You’ll find Ochoa’s agricultural history shaped by destructive river flooding patterns, which eroded fertile topsoil and damaged crops throughout the mid-1900s.

The soil erosion combined with frequent droughts from 1940-1960 devastated local farming operations, causing widespread crop failures and economic hardship.

These environmental pressures forced many farmers to abandon their land, marking a turning point in Ochoa’s shift from farming community to ghost town.

River Flooding Patterns

Throughout Texas history, severe flooding has dramatically shaped the landscape and communities along major river basins, particularly near the Guadalupe and Medina Rivers.

You’ll find that these waterways have experienced extreme events, like the historic 1978 flood that exceeded the 100-year recurrence interval. Effective flood mitigation and river management strategies have become essential to protect local communities and agricultural lands.

Key impacts of river flooding include:

- Destruction of farmland and crops, leading to significant economic losses

- Reshaping of river courses and alteration of natural landscapes

- Water quality degradation affecting aquatic ecosystems

These patterns continue to challenge residents, with some areas receiving up to 48 inches of rainfall in just 24 hours.

Understanding these flood risks helps you better prepare for and respond to these powerful natural events.

Soil Erosion Effects

As soil erosion intensified across Ochoa’s agricultural lands, its devastating effects permanently altered both the landscape and farming potential of the region.

You’ll find the once-fertile topsoil stripped away, leaving behind less productive subsoil that couldn’t sustain the area’s agricultural ambitions. Despite farmers’ attempts at soil conservation and erosion prevention, the persistent loss of nutrients and organic matter severely impacted crop yields and farm incomes.

The erosion’s impact extended beyond the fields, as sediment-filled waterways disrupted irrigation systems and contaminated local water supplies.

You can still see the deep gullies carved into the terrain, making mechanical farming nearly impossible. These environmental challenges, combined with increased operational costs and declining productivity, ultimately contributed to many farmers abandoning their lands, accelerating Ochoa’s transformation into a ghost town.

Drought Impact Timeline

When the devastating 1950s drought struck Ochoa and the surrounding Texas region, it marked the beginning of a series of environmental challenges that would plague the area for decades to come.

You’ll find that recurring drought cycles have persistently shaped the landscape, with particularly severe episodes in the 1970s, 1980s, and 2010-2014.

The impact of water scarcity manifested in several critical ways:

- Reservoir levels plummeted to historic lows, with Lake Dallas reaching just 11% capacity by 1952.

- Streamflows dropped more severely during the 2010-2014 drought than in the 1950s.

- Groundwater depletion intensified as reduced precipitation limited aquifer recharge.

These conditions dealt devastating blows to local agriculture, forcing many farmers to abandon their land and accelerating the area’s transformation into a ghost town.

Abandoned Buildings and Silent Streets

Standing as silent sentinels to a bygone era, Toyah’s abandoned buildings tell the story of a once-thriving community reduced to empty streets and deteriorating structures.

Along silent pathways, you’ll find the haunting W.W. Cole Building, where original bank and pharmacy furnishings remain frozen in time. The imposing Toyah High School looms nearby, while a general store, post office, and gas station with rusty pumps dot the deserted landscape.

Like ghosts of commerce past, empty storefronts and weathered buildings stand sentinel over Toyah’s abandoned streets, preserving fragments of its bustling history.

These abandoned structures, some still containing their original fixtures, paint a stark picture of the town’s decline from its 1910 peak of 1,052 residents.

While the 2004 tornado left its mark, many buildings stand defiant against time’s passage. Local folklore of black-eyed children and mysterious knockings adds an otherworldly dimension to these empty streets.

Legacy in Texas Ghost Town History

Though largely forgotten today, Ochoa’s pivotal role in Texas’s early development mirrors the story of countless frontier settlements that shaped the state’s expansion.

You’ll find that this ghost town’s legacy endures through its contributions to cultural blending and rural identity in the borderlands region.

- The town’s multi-ethnic composition showcases the unique mix of Hispanic and Anglo influences that defined early Texas settlements.

- Community gatherings and local events helped forge a distinct rural identity that’s still celebrated in Texas folklore.

- The remnants serve as a living classroom for understanding socio-economic changes in Texas’s frontier communities.

As part of Texas’s rich ghost town heritage, Ochoa’s story continues to draw visitors and researchers interested in understanding the state’s complex pattern of boom, decline, and cultural preservation.

Preserving Ochoa’s Historical Footprint

As dedicated preservation groups work to maintain Ochoa’s historical legacy, you’ll find a range of initiatives aimed at protecting this significant piece of Texas heritage.

Historical preservation efforts include installing protective fencing, posting signage, and maintaining key structures to prevent vandalism and decay. Modern amenities have been strategically added to make the site more accessible for educational programs and community engagement activities.

You’ll notice school groups regularly visiting the site, using Ochoa as a living classroom to learn about regional development and settler life.

While preservation challenges include limited funding and environmental threats, local organizations continue working to protect both the built environment and natural landscape.

Through careful planning and community support, these efforts help guarantee Ochoa’s story remains intact for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Supernatural Stories or Haunted Locations Associated With Ochoa?

You won’t find verified ghost sightings or documented local legends here – there’s no reliable historical record of supernatural activity, and no paranormal investigators have published findings about this location.

Can Visitors Legally Explore the Remaining Structures in Ochoa Today?

You’ll need explicit permission due to legal regulations, as most structures remain on private property. Contact local authorities for current exploration guidelines before attempting any visits.

What Happened to the Original Land Deeds of Ochoa’s Residents?

Like yellowed pages scattered to the wind, you’ll find the fate of Ochoa’s deeds remains unclear. They were likely transferred to county records, though property disputes and historical preservation efforts haven’t revealed their location.

Were Any Notable Artifacts or Treasures Discovered in Abandoned Ochoa Buildings?

You won’t find documented artifacts discovered or treasure hunting successes in Ochoa’s buildings. While Texas ghost towns have yielded many historical items, there’s no verified record of notable finds in Ochoa’s structures.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Ever Visit or Live in Ochoa?

You won’t find any records of historical visits or notable residents in the town’s files. All evidence suggests it remained a modest farming community without attracting any famous figures during its existence.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bbVM_-giQIE

- https://texashighways.com/travel-news/four-texas-ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- http://genealogytrails.com/newmex/lea/history_vanishedtowns.html

- https://www.expressnews.com/san-antonio-weather/article/ghost-towns-texas-extreme-weather-storms-drought-19877053.php

- https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-weather/article/texas-ghost-towns-extreme-weather-hurricanes-19874031.php

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/ochoa-tx

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TOWNS/Texas_ghost_towns.htm

- http://txgenweb.org/tx/txgenweb9/landmarks/presidio.htm

- https://www.texasalmanac.com/places/paloma-ranch