Rio Bravo emerged as a boomtown after gold’s discovery at Sutter’s Mill in 1848. You’ll find a diverse community once thrived here, with Mexican, Chinese, and American settlers working 10-12 hour days in mines that evolved from simple placer operations to industrial-scale extraction. The town declined in the 1930s when gold mining became unprofitable, leaving behind abandoned structures that tell the story of California’s transformative gold rush era. The silent ruins offer more than meets the eye.

Key Takeaways

- Rio Bravo was established as a boomtown during the California Gold Rush after gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in 1848.

- The town’s economy collapsed by the 1930s when gold extraction became unprofitable, leading to widespread abandonment.

- Mexican settlers formed the primary population, alongside Chinese, Cornish, and African American miners contributing to its diverse culture.

- Mining evolved from simple placer techniques to industrial-scale operations with hydraulic methods by the mid-1850s.

- Abandoned structures now display architectural decay and natural reclamation, with geographic isolation limiting access to the area.

The Discovery of Rio Bravo: A Gold Rush Settlement

While gold was first discovered at Sutter’s Mill on January 24, 1848, by James W. Marshall, Rio Bravo emerged as one of many boomtowns that dotted California’s Sierra Nevada foothills during the subsequent rush.

You’ll find that this settlement formed amid one of history’s largest human migrations, with over 300,000 people flooding into California by 1854.

Rio Bravo’s community dynamics reflected the diverse cultural influences of the Gold Rush era, with settlers arriving from across America, Latin America, China, and Europe.

A vibrant tapestry of cultures converged at Rio Bravo, transforming a simple mining camp into a global microcosm.

Like other mining communities, Rio Bravo developed rapidly as miners abandoned previous trades seeking fortune. Samuel Brannan played a significant role in publicizing such opportunities after announcing the discovery in the California Star newspaper.

The town’s establishment coincided with dramatic shifts in land ownership following the 1851 Land Act, which altered traditional Mexican holdings and accelerated American settlement patterns throughout the region.

The influx of miners led to significant environmental degradation as they employed increasingly destructive techniques like hydraulic mining by 1853 to extract gold from the Sierra foothills.

Life in Early Rio Bravo: Mining Community Culture

As settlers established Rio Bravo following the 1849 gold discoveries, a complex social tapestry emerged that reflected California’s broader mining culture. Mexican settlers formed the primary population, though Chinese, Cornish, and African American miners contributed to the town’s diversity.

You’d find women working alongside men in mining operations, challenging traditional gender roles of the era.

Daily life centered around both work and community gatherings. Residents evolved from makeshift shelters to more permanent structures as the settlement stabilized.

The social hierarchy distinguished between mine owners, skilled laborers, and general workers, while cultural celebrations preserved the Mexican heritage evident in local naming conventions.

Despite harsh working conditions in stamp mills and underground shafts reaching 300 feet, Rio Bravo’s residents maintained cultural traditions that bound their diverse community together. Like many camps that had run out of gold, Rio Bravo eventually declined as miners departed to seek more profitable strikes elsewhere.

Economic Boom: Gold Mining Operations and Local Business

Rio Bravo’s economic prosperity depended heavily on the evolving techniques miners employed, from simple panning to hydraulic operations that extracted gold from quartz veins with increasing efficiency.

You’d find the town’s commercial district thriving with saloons where miners spent their earnings and supply stores that provided essential tools, clothing, and foodstuffs at premium prices. These businesses flourished alongside transportation routes that facilitated the movement of mining equipment and bullion shipments.

The local economy followed distinct seasonal patterns, with winter rains limiting mining activities while summer droughts created different operational challenges for both mining ventures and supporting businesses. Few Rio Bravo miners achieved the wealth they had initially dreamed of, as harsh conditions and inflated prices consumed most of their gold findings.

Mining Techniques Evolved

When gold was first discovered in the California goldfields surrounding Rio Bravo, miners employed remarkably simple techniques to extract the precious metal. Your typical prospector began with basic placer mining – panning streambeds with pickaxes and shovels.

As surface gold depleted, miners developed “coyoteing,” digging shafts 6-13 meters deep with horizontal tunnels to reach gold deposits.

By mid-1850s, you’d witness a dramatic shift toward industrial-scale extraction. Hydraulic techniques revolutionized mining, using high-pressure water to erode entire hillsides. This required substantial capital investment, transforming individual enterprises into corporate operations. Chinese immigrants became vital to these operations, eventually comprising 20% of mining communities by the late 1850s.

- Mercury-coated copper plates improved gold recovery from crushed ore

- Hard-rock mining targeted gold in quartz veins up to 40 feet deep

- Cast iron shoes and rotary stamps enhanced stamp mill efficiency

- Vast networks of flumes channeled water from higher elevations

Today, major corporations continue these industrial practices with open-pit cyanide mining methods throughout California’s Sierra region.

Saloons and Supply Stores

The bustling heart of Rio Bravo’s economic activity centered around its numerous saloons and supply stores, which functioned as more than mere businesses.

Saloons became the nexus of social life, where you’d find miners exchanging information, negotiating labor contracts, and selling their gold findings. This saloon culture provided entertainment and respite from the harsh mining existence while generating substantial revenue for proprietors. Similar to merchants during the Gold Rush era, many saloon owners became millionaires like Brannan through these mining-related business ventures.

Meanwhile, merchant influence extended beyond simple retail transactions.

Supply store owners often accumulated more reliable wealth than the miners themselves by providing essential tools, clothing, and food at premium prices. Similar to the rapid economic expansion seen across California during the Gold Rush era, these shrewd entrepreneurs frequently offered credit systems that kept mining operations viable despite miners’ irregular income.

Together, saloons and supply stores created an interdependent economic ecosystem that thrived as long as gold continued flowing from Rio Bravo’s hills.

Seasonal Economic Fluctuations

Driven by the ebb and flow of seasonal conditions, Rio Bravo’s economic significance followed predictable yet dramatic patterns throughout the year. The gold mining operations that sustained the town operated primarily during spring and summer when weather conditions permitted access to remote claims.

During winter, heavy rains and snow slowed or halted operations in many areas, particularly in higher elevations. The introduction of cyanide processing in the 1890s allowed for more efficient gold recovery even during seasonal slowdowns.

- Economic cycles mirrored nature’s calendar—prosperity in fair weather, contraction in harsh

- Seasonal labor markets expanded and contracted as miners followed opportunity

- Local businesses adjusted inventory and staffing based on predictable mining schedules

- Mining companies stockpiled ore during active months to maintain some winter operations

These fluctuations created a rhythm of boom and bust that defined life in Rio Bravo, with businesses and miners alike adapting to the inevitable cycle.

Geographic Features and Natural Resources

Situated in the southern reaches of California’s San Joaquin Valley, Rio Bravo Ghost Town occupies a distinctive geographic position in Kern County, approximately 7.25 miles south of Shafter.

As you explore Quartzburg’s rich mining history, you’ll uncover tales of fortune seekers and the bustling life that once defined this community. The remnants of old mines and artifacts scattered throughout the area offer a glimpse into the past, inviting visitors to reflect on the hard work and perseverance of its early inhabitants. Guided tours and informational plaques can enhance your understanding of how Quartzburg played a significant role in California’s mining era.

At 318 feet above sea level, you’ll find it nestled on flat, arid terrain typical of the region, with the Sierra Nevada foothills visible in the distance.

Rising just 318 feet above sea level, this forgotten settlement rests on parched flatlands, with distant Sierra Nevada peaks sketching the horizon.

The area’s semi-arid climate shaped its agricultural practices, with rich soil supporting cotton and grain farming operations.

Water management became essential as groundwater served as the lifeblood for both irrigation and community needs.

The Southern Pacific Railroad‘s presence facilitated the transport of these agricultural products to distant markets.

Despite its economic potential, Rio Bravo faced environmental challenges including soil degradation, groundwater depletion, and habitat loss—factors that ultimately contributed to its abandonment.

Everyday Life in a 19th Century Mining Town

Life in Rio Bravo revolved around a rigorous social hierarchy that mirrored typical 19th century mining settlements throughout the American West. Daily routines began before dawn, with miners laboring 10-12 hours in dangerous conditions while women maintained households or ran boarding establishments.

You’d find community roles clearly defined—mine owners and merchants at the top, with service providers forming the middle class.

- Your home would’ve been a simple wooden structure shared with others, vulnerable to devastating fires.

- You’d subsist primarily on beans, bacon, and coffee, with fresh produce a rare luxury.

- After grueling workdays, you’d seek entertainment at the saloon, enjoying card games and occasional music.

- Your children would attend makeshift schools if available, though many worked alongside adults.

The Slow Decline: When the Gold Ran Out

As you wander through Rio Bravo today, you’ll notice the stark economic vacuum left when gold extraction became financially untenable by the 1930s, with fixed government prices at $35 per ounce making operations unprofitable.

The once-thriving commercial district stands largely abandoned, with weathered storefronts and collapsing mine structures telling the silent story of capital flight as hard rock mining companies folded under technical and financial pressures.

You’re witnessing the physical remnants of the economic shift that forced miners to abandon independent operations, transforming the vibrant town into the shell that remains when extractive industries can no longer sustain communities.

Economy After Gold

While the initial gold rush brought explosive prosperity to Rio Bravo, the inevitable depletion of accessible placer deposits by the late 1850s transformed the region’s economic landscape.

The town experienced dramatic economic changes as mining operations shifted from individual prospecting to capital-intensive industrial extraction. Labor shortages emerged as disappointed forty-niners migrated to newer mining districts in the Klamath Mountains and northern Sierra Nevada.

- Merchant businesses collapsed as their customer base evaporated

- Agricultural conversion attempts provided limited economic alternatives

- Transportation infrastructure became underutilized as commerce declined

- Former mining equipment and facilities became stranded assets

You’d have witnessed the painful shift from small-claim operations to corporate mining enterprises requiring substantial investment.

Some settlers attempted to establish farms and orchards, repurposing existing infrastructure, but these efforts proved insufficient to sustain Rio Bravo’s former liveliness, ultimately leading to its abandonment.

Empty Buildings Remain

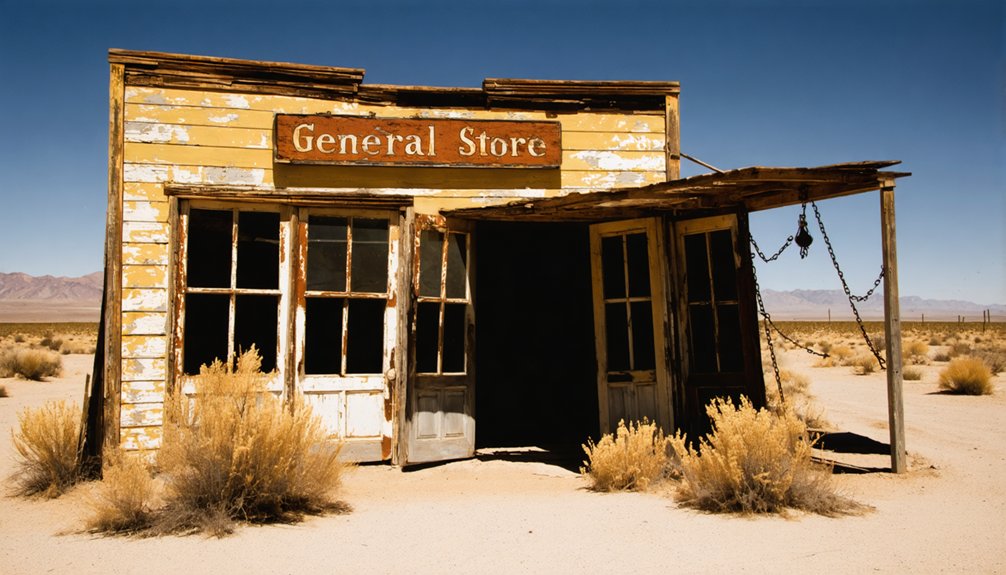

The desolate wooden structures of Rio Bravo stand as silent witnesses to the town’s economic collapse after the gold deposits dwindled. As you wander through the site today, you’ll encounter ghostly remnants of homes, saloons, and commercial buildings constructed with local materials in typical mining-era style.

These abandoned structures showcase significant architectural decay—weathered boards, crumbling foundations, and partial walls still delineate what was once a thriving community. The buildings, now exposed to decades of harsh elements, continue deteriorating with minimal preservation efforts to halt their decline.

Nature steadily reclaims these spaces; vegetation pushes through wooden floors and around foundations. The skeletal buildings represent California’s boom-and-bust mining cycle, offering you a tangible connection to the past that’s unfiltered by modern intervention—a raw glimpse into frontier life.

Abandonment and Transformation Into a Ghost Town

Following the depletion of its valuable mineral deposits, Rio Bravo experienced a steep economic decline that ultimately led to its complete abandonment. Unlike other ghost towns that found new life through tourism, Rio Bravo’s remote location and infrastructure limitations prevented any meaningful revitalization.

The social dynamics of the community collapsed as families migrated to more prosperous regions, leaving behind deteriorating wooden structures that exemplify classic ghost town aesthetics.

As prosperity fled Rio Bravo, so did its people, leaving only weathered timber shells as silent monuments to forgotten dreams.

- Buildings succumbed to harsh weather and natural decay, with environmental impacts visible in nature’s reclamation

- Population exodus occurred rapidly as mining jobs disappeared and supporting industries failed

- Geographic isolation accelerated the town’s demise by limiting access to essential supplies and services

- Absence of preservation efforts guaranteed Rio Bravo’s complete transformation from bustling mining camp to forgotten historical footnote

Exploring Rio Bravo Today: What Remains

Visitors seeking remnants of Rio Bravo’s once-thriving mining community will find themselves largely disappointed by the sparse physical evidence that remains today.

The site accessibility is challenging, requiring off-road navigation or hiking across undeveloped terrain to reach coordinates 35°17′49″N 119°03′24″W in Kern County.

Nature has reclaimed this forgotten corner of California’s mining history. You’ll encounter only scattered foundation ruins, partial walls, and occasional mining equipment fragments—all steadily disappearing into the landscape.

The environmental impact of time and weather has transformed what was once a bustling town into desert shrubland where wildlife now roams freely.

No facilities, signage, or maintained pathways exist for explorers. Unlike popular ghost towns like Bodie, Rio Bravo remains largely undocumented and unexplored by formal archaeological research.

Historical Legacy: Rio Bravo’s Place in California’s Mining History

While physical traces of Rio Bravo have largely vanished from the landscape, its historical significance within California’s mining narrative remains firmly etched in the state’s development story.

When you explore Kern County’s mining heritage, you’ll find Rio Bravo represented an integral chapter in the gold rush that transformed California after 1851.

- Part of a region that produced over 1.7 million ounces of gold through 1959

- Witnessed the evolution from simple placer mining to advanced mining innovations

- Contributed to Kern County’s $46 million gold production value

- Offers opportunities for historical preservation of California’s mining technology evolution

Rio Bravo’s legacy extends beyond its physical remains, demonstrating how mining districts shaped California’s economic foundation and technological advancement during the post-Gold Rush era.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Famous Residents Who Lived in Rio Bravo?

No, there weren’t any famous residents in Rio Bravo. Historical documentation and census records don’t identify any individuals of historical significance who lived in this small, transient settlement.

Did Rio Bravo Experience Any Major Disasters or Epidemics?

Like many fading frontier memories, Rio Bravo’s records show no specific epidemic outbreaks or major disaster impacts, though it likely shared regional challenges affecting California ghost towns during their decline.

What Happened to the Buildings After the Town Was Abandoned?

After abandonment, you’ll find Rio Bravo’s buildings succumbed to severe deterioration from weather, vandalism, and scavenging. Unlike other ghost towns, no historical preservation efforts protected the structures, leaving only foundations and partial ruins today.

Are There Any Legends or Ghost Stories Associated With Rio Bravo?

Unlike more famous ghost towns, you’ll find no well-documented ghostly encounters or local folklore specifically tied to Rio Bravo. Historical records don’t mention paranormal legends associated with this former settlement.

Can Visitors Legally Collect Artifacts From the Rio Bravo Site?

No, you absolutely cannot collect artifacts legally. California’s stringent legal regulations prohibit unauthorized collection, emphasizing artifact preservation instead. You’d risk hefty penalties for removing historical items from the site.

References

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OD9M6MP6RRU

- https://www.californist.com/articles/interesting-california-ghost-towns

- https://www.camp-california.com/california-ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C6d838Wa8Ag

- https://www.bajabound.com/bajaadventures/bajatravel/las_flores_ghost_town.php

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_California

- https://www.truewestmagazine.com/article/the-bad-man-from-bodie/

- https://mchsmuseum.com/local-history/american-era-settlement/influence-of-the-gold-rush/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/California_gold_rush

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/294833077.pdf