You’ll find Silver, Texas, in northwestern Coke County, where silver ore discovery in 1880 transformed a remote spot into a thriving mining town of 4,000 residents. At its peak, the Presidio Mining Company produced 92% of Texas’s silver, yielding over 30 million ounces along with lead and zinc. The town’s decline began in the 1940s due to economic pressures, and today its abandoned structures tell a compelling story of boom-and-bust in the American West.

Key Takeaways

- Silver, Texas began as a prosperous mining town in 1880 after John Spencer discovered silver ore in the area.

- At its peak, the town’s population reached 4,000 residents and produced 92% of Texas’s silver through the Presidio Mining Company.

- The town declined rapidly in the 1940s due to rising production costs and labor issues in silver mining operations.

- Today, Silver is a ghost town located in northwestern Coke County at the intersection of Highway 208 and RM 2059.

- The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and is currently undergoing preservation efforts.

Location and Geographic Features

Located at the intersection of Texas State Highway 208 and Ranch to Market Road 2059, Silver stands as a ghost town in northwestern Coke County, Texas.

At the crossroads of rural Texas highways, Silver remains frozen in time, a silent testament to Coke County’s past.

You’ll find it positioned at coordinates 32°07’N and 100°68’W, about 17 miles northwest of Robert Lee and 27 miles southeast of Colorado City.

The land use patterns reflect Silver’s position within Texas’s central plateau region, where the topography analysis reveals an elevation of 2,100 feet above sea level.

You’re surrounded by semi-arid terrain typical of west Texas, with sparse vegetation and gently rolling hills that’ve long supported ranching activities.

The site’s positioning at a highway junction makes it accessible despite its remote setting, while its placement between Robert Lee, Colorado City, and Big Spring creates a strategic triangle for regional connectivity.

Like the noble metal silver, the town remains remarkably unreactive to the harsh environmental conditions of the Texas climate.

For clarity in navigation, the town’s location requires precise linking to distinguish it from other similarly named places in Texas.

Origins and Settlement History

You’ll find the town’s beginnings in an 1880 silver ore discovery by rancher John Spencer near Fort Davis, which caught the attention of Colonel William R. Shafter.

The settlement quickly grew around the silver strike and was named after Shafter, who along with his military associates acquired key land for mining development.

The establishment of the town’s first post office in 1890 marked its evolution from a mining camp into an organized community, where ranching activities complemented the growing mining operations. Early Spanish explorers had conducted ore prospecting in the area as far back as the 1600s. The post office was established by Thomas J. Wiley, who helped organize the growing settlement.

Early Mining Town Roots

While Spanish prospectors first explored the Shafter area for silver in the early 1600s, the region’s mining history truly began with Franciscan friars who discovered and operated silver mines near El Paso around 1680.

Their mining techniques were later concealed to prevent Jesuit control, though records helped rediscover these locations.

Similar to the copper and tin mining in the Franklin Mountains that emerged later in 1899, the area’s silver production potential emerged through three key developments:

- S.B. Buckley’s 1876 mineral survey identified valuable deposits of lead, silver, and copper.

- John W. Spencer’s discovery of a rich silver ore ledge in 1880.

- Colonel William R. Shafter’s formation of a mining partnership that acquired 2,560 acres.

The Presidio Mining Company was officially organized in 1883 with substantial financial backing from San Francisco investors.

This foundation led to the Presidio Mine‘s establishment, which would produce 92% of Texas’s silver and stretch 4,000 feet long and 1,500 feet deep during its peak operations.

Ranching Community Development

As mining operations began to wane in Silver, a resilient ranching community emerged through strategic land acquisitions along Cibolo Creek and the Chinati Mountains.

You’ll find that early landowners, including Colonel William R. Shafter and his military associates, secured approximately 2,560 acres through state government petitions, establishing the foundation for ranching techniques that would sustain the area’s dwindling population. One of these pioneering ranchers was Milton Favor, who established the first Anglo ranch in the Big Bend region.

The geography proved ideal for various cattle breeds, with Cibolo Creek providing essential water sources and the Chinati Mountains offering natural grazing lands. The American Metal Company acquisition of local properties in 1926 further shaped the region’s transition from mining to ranching operations.

Rather than clustering in a dense settlement, ranching families established scattered homesteads along the creek, developing self-sufficient operations that often combined cattle ranching with freight hauling.

They built corrals, fences, and water wells, transforming the former mining infrastructure into a practical ranching community that endured despite the harsh desert conditions.

Mining Operations and Economic Peak

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Silver, Texas emerged as a notable mining hub following the discovery of silver mineralization in 1880. The mercury-based mill operations transitioned to more efficient cyanide processing, increasing ore handling capacity by over 60%. The manual labor tools initially used by miners gave way to more sophisticated extraction methods as the industry developed.

Silver’s emergence as a prominent Texas mining center in 1880 marked the beginning of a transformative era in regional history.

The area’s mining techniques evolved as operations expanded, with the Presidio Mine leading production efforts amid economic fluctuations that challenged the industry’s stability.

The district’s remarkable achievements included:

- Production of over 30 million ounces of silver, along with substantial amounts of lead and zinc

- Support of a thriving community of 4,000 residents at its peak

- Development of essential infrastructure, including railway connections and mining facilities

You’ll find that despite technological limitations and environmental challenges, the mining operations persisted through market changes and security concerns, shaping the region’s economic landscape until the Great Depression considerably impacted its profitability.

Daily Life in Early Silver

In early Silver, you’d find mining families living in modest wooden or adobe homes, where daily routines revolved around the demanding work schedules of the mines.

Your children would attend the local school established in 1890, which served as a cornerstone of community education and social development.

Your social life would center around the Sacred Heart Church, two saloons, and a dance hall, where community gatherings strengthened bonds among the town’s residents.

Mining Families’ Daily Routines

Life for the three to four hundred mining families in Silver revolved around strict daily routines dictated by the demands of silver extraction.

Men worked long hours in the open-pit and underground mines, while women managed household duties and occasional support roles in local businesses. Family dynamics centered on the mining schedule, with daily activities organized around work life in the mines.

You’d find these core elements of a mining family’s routine:

- Men working 700 feet underground or hauling silver ore via tramway systems

- Women maintaining homes, cooking meals, and sometimes working in shops or schools

- Children splitting time between education at the local school and helping with family duties

Housing remained simple but practical, with company-provided units positioned near the mining sites for quick workplace access.

Community Social Activities

Despite the demanding nature of mining work, Silver’s residents maintained a vibrant social life centered around several key gathering spots in the early 1900s.

You’d find two popular saloons and a dance hall serving as primary venues for community gatherings, where miners and their families could unwind after long shifts. The company store doubled as an informal meeting place where you’d catch up on local news and socialize with neighbors.

Cultural exchanges flourished as Mexican citizens, Black Americans, and California miners mixed in these shared spaces. You’d experience diverse influences in music, food, and celebrations throughout town.

The company doctor’s office and post office became natural hubs for social interaction, while casual gatherings often spilled into the streets and open spaces near company housing, creating a close-knit community despite the controlled environment.

Local School Experience

Education in Silver evolved alongside the town’s changing fortunes, from a modest schoolhouse to a million-dollar complex by 1949. The school history reflected the town’s oil boom prosperity, serving children from both local families and nearby oil camps.

Your children’s educational experience would’ve included:

- Daily walks or short commutes from oil camps to the school complex

- Traditional curriculum focused on reading, writing, arithmetic, and practical skills

- Community activities that blended church events with school functions

The educational impact of Silver’s school system peaked during the oil boom years when enrollment grew with the town’s population of 1,000 residents.

As oil production declined in the mid-1960s, falling enrollment led to consolidation with Robert Lee Independent School District, marking the end of Silver’s educational era.

The Decline and Abandonment

While Silver, Texas once thrived with a population of 4,000 residents, the town’s decline began in the 1940s due to mounting economic pressures.

You’ll find that several factors converged to seal the town’s fate: rising production costs made silver mining unprofitable, while labor shortages and unionization attempts disrupted operations.

The economic ramifications intensified when both Marfa Army Air Field and Fort D.A. Russell closed in the mid-1940s, removing essential military support from the area.

The closure of two key military installations in the 1940s dealt a severe economic blow to Silver’s already fragile economy.

The social consequences were devastating as the population plummeted to less than 100 within a decade.

Resource depletion, including the exhaustion of local wood supplies by 1910, forced costly alternatives like trucking in oil fuel.

Notable Buildings and Structures

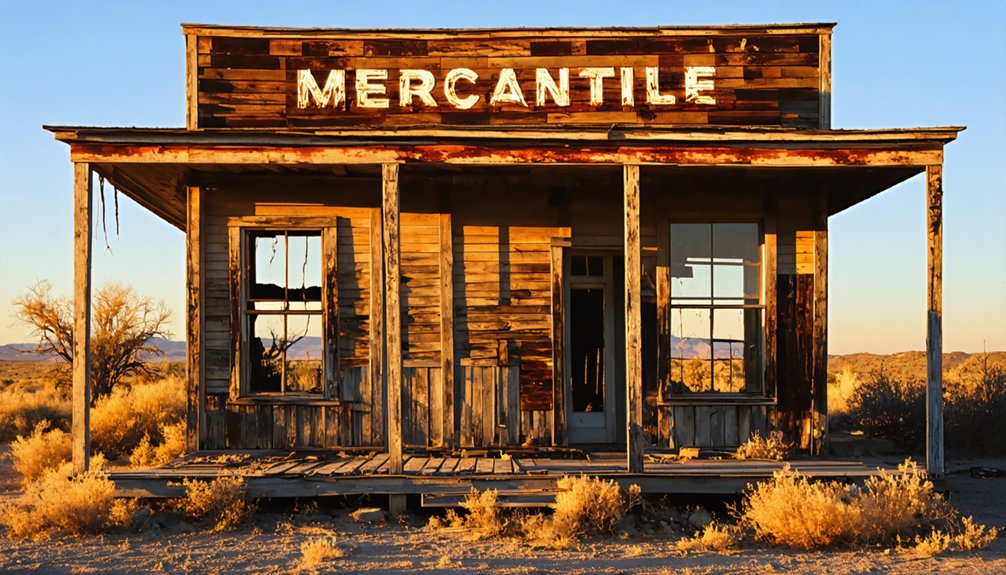

Remnants of Silver’s mining heritage dot the landscape through its notable structures and buildings.

You’ll find architectural significance in the well-preserved Sacred Heart of Jesus Catholic Church, built with resilient adobe that’s withstood desert conditions. The church’s cemetery nearby serves as a solemn record of the town’s mining era.

- The Presidio Mining Company ruins showcase the town’s industrial core, with scattered remains of processing equipment and company buildings.

- Worker housing foundations and commercial building remains reveal the layout of daily life, featuring adobe and stone construction adapted to the harsh environment.

- The atmospheric Shafter Cemetery, known for its distinctive grave markers and local ghost stories, stands as a haunting reminder of the community’s past.

Present-Day Ghost Town Experience

Today, visiting Silver offers an authentic ghost town experience in the remote desert landscape of Presidio County, West Texas.

Venture into the heart of West Texas, where Silver’s desert ruins tell tales of a forgotten frontier mining town.

You’ll find yourself immersed in a true abandoned mining settlement, where desert wildlife now roams freely among weathered structures and mining relics.

As you explore this representation of boom-and-bust mining history, you’ll need to plan carefully for the isolated location.

Ghost town tourism here means bringing adequate water, fuel, and supplies, as you won’t find services for many miles.

Your exploration safety depends on watching for unstable buildings, abandoned mine shafts, and harsh desert conditions.

You’ll want a suitable vehicle for unpaved roads, especially during adverse weather.

The payoff is unparalleled access to authentic mining artifacts, stunning desert vistas, and the profound quiet of a forgotten Texas town.

Historical Preservation Efforts

Since its addition to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, the Shafter Historic Mining District has become a focal point for dedicated preservation efforts.

The Tidewater & Big Bend Foundation leads restoration initiatives aimed at returning structures to their 1900s glory, though they’ve faced significant preservation challenges along the way.

You’ll find several key preservation projects underway:

- Acquisition and restoration of historic buildings, including the Howell Package Store

- Development of a “living history” experience featuring museums and period actors

- Creation of visitor housing facilities modeled after Colonial Williamsburg

Securing funding sources remains essential for these ambitious plans.

While initial setbacks occurred when a Canadian company wouldn’t sell the silver mine, current efforts focus on structural preservation rather than historical interpretation, with community engagement playing an important role.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Documented Paranormal Activities or Ghost Sightings in Silver?

You won’t find officially documented ghost stories or haunted locations specifically in Silver. While nearby mining towns have verified paranormal claims, Silver’s spooky reputation stems from atmosphere rather than confirmed sightings.

What Happened to the Original Residents After Leaving Silver?

Like scattered seeds, the original residents of this ghost town spread across Texas cities, Mexico’s borderlands, and nearby towns, finding work in ranching, manufacturing, and railroads after mining’s decline.

Were There Any Famous Outlaws or Notable Incidents in Silver?

You won’t find famous outlaws directly linked to Silver, though nearby mining towns had their share of vigilantes and gunfights. Most notable incidents involved mining disputes and hired fighting men.

Is Camping or Metal Detecting Allowed at the Silver Ghost Town?

You’ll need to check local camping regulations and metal detecting rules before visiting. Contact county officials or landowners for permits, as both activities may be restricted or prohibited in historical areas.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Silver Area?

You won’t find definitive evidence of original Native tribes in Silver’s exact location, though historical records show Lipan Apache, Comanche, and Tonkawa peoples moved through this contested Central Texas territory.

References

- https://www.texasstandard.org/stories/the-former-richest-acre-in-texas-fell-hard-when-demand-for-silver-took-a-dive/

- https://authentictexas.com/shafter/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/shafter-texas/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shafter

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P1rg6BMWKoE

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TexasTowns/Silver-Texas.htm

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/silver-tx

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/shafter-tx

- https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth39648/