You’ll find Swastika, Texas was a bustling coal mining town established in the late 1860s, named after the ancient good luck symbol long before its Nazi appropriation. The settlement peaked in 1925, producing 1,500 tons of coal daily with a population of 500 by 1929. The Texas & Western Railroad connected it to northern markets, but the switch from coal to oil led to its abandonment by the 1960s. The town’s complex history reveals deeper cultural significance in American mining communities.

Key Takeaways

- Swastika was a mining company town that reached its peak in 1929 with 500 residents and 1,500 tons of daily coal production.

- The Texas & Western Railroad extension connected Swastika to northern Texas markets, facilitating coal transport and commerce.

- The town was named after the swastika symbol, which represented good fortune in American culture before World War II.

- Economic decline began in the 1950s when railroads shifted from coal to oil fuel, leading to the town’s abandonment.

- By the 1960s, Swastika had become a ghost town, with no physical remnants or archaeological evidence remaining today.

The Rise and Fall of a Mining Settlement

While coal mining operations in the Dillon Canyon area began in the late 1860s, Swastika’s establishment as a company town marked a significant development in New Mexico’s mining industry.

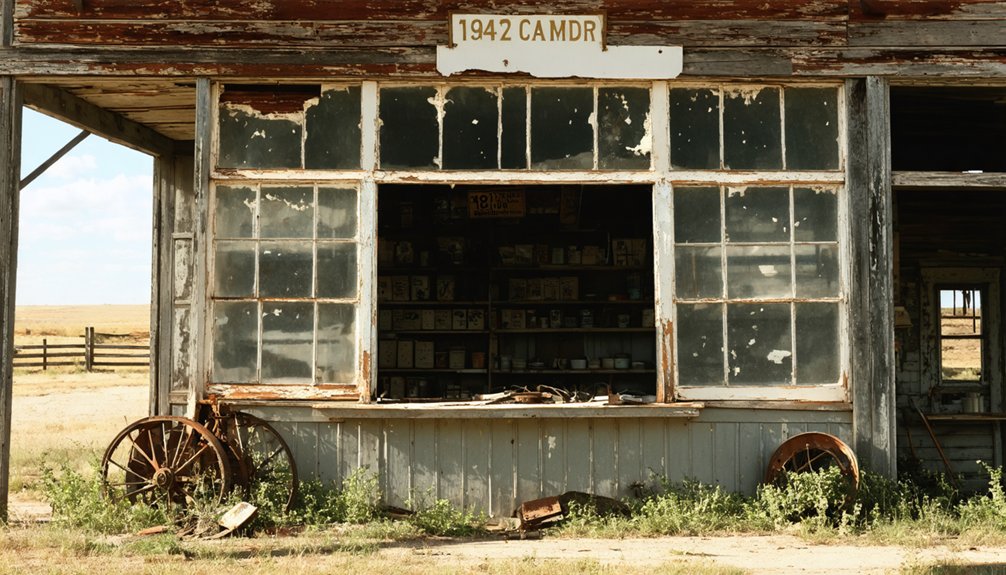

You’ll find that by 1925, the settlement had evolved into a thriving community, producing an impressive 1,500 tons of coal daily and housing essential amenities like a post office, school, and company store. The Swastika Pool discovery near Olney in 1924 marked another important mining development in the region.

The town’s cultural significance grew as its population reached 500 residents by 1929. The Swastika Fuel Company operated as a key subsidiary of the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Company, headquartered in nearby Raton.

You’d have witnessed a diverse community, particularly notable for its Italian immigrant population, who contributed to the town’s identity through community events and their celebrated soccer team.

However, by the 1950s, the railroad’s shift from coal to oil led to the town’s decline, transforming this once-bustling mining settlement into a ghost town by the 1960s.

Cultural Origins of the Town’s Name

Before the Nazi regime’s appropriation of the symbol in the 1930s, you’ll find that the swastika represented good fortune across many cultures, including Native American tribes who considered it sacred.

You can trace the town’s naming to this original positive symbolism, as the swastika represented prosperity and well-being to local inhabitants in the early 1900s. The symbol had been documented as a good luck charm in American culture since the late 1800s, as evidenced by its inclusion in an 1894 Smithsonian publication.

When studying the historical context of this Texas settlement, you’ll understand that its founders chose the name to invoke luck and success during the area’s mining boom, reflecting the symbol’s widespread positive associations in pre-World War II America. The ancient Greek cross design was adapted with equal-length shafts bent at right angles, creating the distinctive symbol.

Native American Sacred Symbol

The sacred symbol known as the “Whirling Log” held profound significance among Native American tribes, representing concepts of good fortune, wellness, and spiritual harmony long before its appropriation by other cultures.

You’ll find evidence of this symbolic significance throughout indigenous artifacts, from pottery and blankets to ceremonial beadwork. In 1909, Osage Chief Peter Bigheart proudly displayed this cultural heritage by wearing a “Whirling Log” lapel pin as part of his traditional attire.

The symbol’s integration into daily life extended to public events, where Dewey Roundup contestants showcased Pendleton saddle blankets featuring the ancient motif. The symbol originated as a representation of good fortune and well-being across many ancient civilizations. The symbol’s roots can be traced back to ancient Sanskrit origins, connecting it to broader historical traditions of spirituality and well-being.

While modern interpretations have shifted dramatically, many tribes maintain their connection to the symbol’s original meaning of divine protection and spiritual well-being, preserving its sacred role in their cultural traditions.

Good Fortune Before Nazism

Throughout human history, many communities adopted the Sanskrit-derived swastika symbol to represent good fortune and prosperity, including the small Texas settlement that would later become a ghost town.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, you’d find the swastika displayed prominently across Western nations as a sign of good luck and cultural significance. The area’s Swastika Pool production in 1924 exemplified this optimistic naming tradition in the region. The symbol’s original meaning of well-being in Sanskrit reflected its positive historical significance.

Before its appropriation by the Nazi regime, the symbol appeared frequently in European and American designs, architecture, and civic planning. This widespread acceptance reflected the symbol’s ancient origins spanning over 7,000 years of human civilization.

Towns across America, like this Texas settlement, embraced the swastika’s original meaning of well-being, following a global tradition that included ancient Troy, indigenous American cultures, and various European societies.

Local Meaning and Usage

While many American communities adopted symbolic names reflecting their aspirations, Swastika, Texas derived its name from an ancient Sanskrit symbol representing prosperity and good fortune.

In its local significance, the symbol appeared throughout Wheeler County on cattle brands, homes, and buildings as a protective emblem against natural disasters, particularly tornadoes.

You’ll find that before World War II, the historical context of the swastika in Northwest Texas was deeply rooted in positive cultural associations, shared by miners, settlers, and Native American communities alike. Much like the diverse workforce in Thurber, the town attracted immigrant laborers from various countries who brought their own cultural interpretations of the symbol.

The counterclockwise design, distinct from the Nazi variant, was commonly integrated into local architecture and everyday items, reflecting the area’s multicultural heritage and belief in the symbol’s power to bring luck and protection.

Local artisans and jewelers frequently incorporated peace and good luck symbols into their crafts before the symbol’s meaning was forever changed by World War II.

Native American Influence and Symbolism

Long before its tragic appropriation by Nazi Germany, sacred swastika symbols held deep cultural significance among Native American tribes across the southwestern United States, including Texas.

You’ll find that tribes like the Navajo interpreted it as a “whirling log” symbolizing healing and life cycles, while the Hopi viewed it as representing their wandering clans’ journey and continuity.

This swastika symbolism manifested throughout Native American art, architecture, and daily life in Texas.

You’ll discover it woven into textiles, painted on pottery, and carved into jewelry – each instance representing protection, prosperity, and spiritual well-being.

The symbol’s cultural significance was so respected that the 45th Infantry Division adopted it on their patch to honor their Native American members, though they later replaced it with a thunderbird in 1939.

Railroad Connections and Economic Impact

You’ll find that Swastika’s economic backbone rested on its critical railroad connection through the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Railroad’s “Swastika Line,” which operated from 1902 to 1915.

The 105-mile rail section transformed the town into a bustling transportation hub, connecting essential mining operations to broader markets and fostering the growth of ancillary businesses like the Swastika Mining Company.

The railroad’s eventual dismantling during World War II for scrap metal marked the beginning of the town’s decline, contributing to its eventual ghost town status.

Rail Lines and Mining

During the early 1900s, the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Railway Company played a significant role in railroad expansion through Swastika, Texas, marking its equipment with a distinctive red swastika symbol. The 105-mile Swastika Line connected important mining centers, including Raton and Cimarron, enabling efficient transportation of coal and minerals.

You’ll find that mining techniques evolved alongside rail development, as the SLRM&P constructed key infrastructure between 1906-1907.

When Santa Fe Railway acquired SLRM&P in 1913, they maintained operations until restructuring as Rocky Mountain and Santa Fe in 1915. The rail-mining partnership proved fundamental for accessing remote sites and transporting resources to broader markets.

However, by 1935, declining mining activity led to the Des Moines line’s abandonment, with some tracks later salvaged for World War II efforts.

Transportation Hub Development

Beyond its mining operations, Swastika’s development as a transportation hub transformed the town into a significant regional nexus.

You’ll find the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain & Pacific Railroad, nicknamed the “Swastika Route,” played a key role by connecting the area to major markets across 105 miles of track. This transportation infrastructure enabled the local mine to reach peak production of 1,500 tons daily by 1925.

The Texas & Western Railroad’s extension further enhanced Swastika’s connectivity, establishing important links to northern Texas markets.

This network supported rapid economic growth, as you’d see reflected in the town’s population surge to 500 residents by 1929. The rail system didn’t just move coal – it facilitated diverse commerce, brought necessary supplies to company stores, and attracted immigrant workers, particularly from Italy.

Railroad Industry Decline

While the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain & Pacific Railroad operated its Swastika Line from 1902 to 1915, you’ll find its ultimate decline marked a turning point in the region’s railroad transportation history.

The line’s demise, accelerated by World War II’s demand for scrap metal, led to a devastating economic decline in Swastika, Texas.

- Coal mining operations lost essential transport infrastructure

- Local merchants and service providers faced sharp revenue drops

- Railroad worker jobs disappeared as tracks were dismantled

- Transport connectivity disruption isolated the community

- War effort scrap metal demands sealed the line’s fate

The railroad’s collapse proved particularly impactful because it served as the area’s economic backbone, connecting coal mines to markets.

When the tracks were removed around 1941, you couldn’t find a path to recovery, ultimately transforming Swastika into a ghost town.

World War II’s Effect on Local Identity

As World War II transformed communities across America, the small town of Swastika, Texas experienced profound shifts in its local identity. The war’s patriotism impact reached every corner of the state, challenging residents to reconsider their town’s name and its symbolic meaning.

You’ll find that community roles evolved dramatically as locals participated in rationing programs and supported the broader war effort, much like other Texas towns near POW camps and military installations.

The once-innocent meaning of the town’s name collided with wartime realities, as the symbol became irreversibly associated with Nazi Germany. This cultural shift forced residents to confront questions about their community’s identity within the context of national unity and heightened patriotic sentiment, reflecting the deeper transformations occurring in small towns across America during this pivotal period.

Historical Legacy and Modern Archaeological Findings

Through meticulous cartographic research, Swastika’s existence can be traced primarily through historical maps, appearing first on 1920s General Land Office documents of Hale County and later on 1930 highway maps.

Modern archaeological significance remains limited, as you’ll find no physical remnants of this enigmatic location.

Despite extensive field research, this vanished settlement leaves no trace in the physical record, existing only in cartographic memory.

- No documented archaeological excavations or surveys exist

- Historical documentation vanishes after the late 1930s

- Unlike typical ghost towns, no cemetery or structural remains survive

- Site’s potential as a rail switch stop suggests minimal development

- Absence from ghost town registries indicates limited settlement status

The site’s historical legacy presents a unique case study in how global events can erase local place names, while its archaeological record – or lack thereof – challenges traditional assumptions about Texas ghost town preservation patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Residents Who Lived in Swastika After Its Name Changed?

Like scattered seeds in a West Texas wind, you’ll find residents’ stories merged into nearby towns and cities naturally – they weren’t forcibly moved but gradually dispersed for economic opportunities.

Were There Any Documented Conflicts Between Swastika Residents and Neighboring Communities?

You won’t find any documented historical conflicts between residents and neighbors – available records show no evidence of community relations problems or violent encounters in the town’s brief history.

Did Local Newspapers Cover Stories About Daily Life in Swastika?

You won’t find any confirmed local journalism coverage of daily life in this town – research of Texas newspaper archives and historical databases reveals no surviving articles about community happenings there.

What Businesses and Services Operated in Swastika Besides Coal Mining?

You’d find general merchandise stores, lodging houses, food establishments, doctor’s offices, schools, and various service establishments like blacksmiths and carpenters supporting the mining community’s daily needs.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Accidents Reported in Swastika?

You won’t find any documented crime history or accident reports from this location – historical records show no significant incidents during its brief existence as a possible railroad switch point.

References

- http://www.pampamuseum.org/-the-orginial-swastika.html

- https://www.southernthing.com/ruins-in-texas-2640914879.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8uH3gIzqnVM

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_use_of_the_swastika_in_the_early_20th_century

- http://dodstrakigt.blogspot.com/2010/09/svastikor-vi-minns-swastika-texas.html

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TexasPanhandleTowns/Swastika-Texas.htm

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TOWNS/Texas-Ghost-Towns-5-Texas-Panhandle.htm

- https://krtnradio.com/wp/2024/04/29/the-swastika-symbol-an-integral-part-of-ratons-past/

- https://www.emnrd.nm.gov/mmd/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/DutchmanSwastikaOSMREnomination-2021.pdf