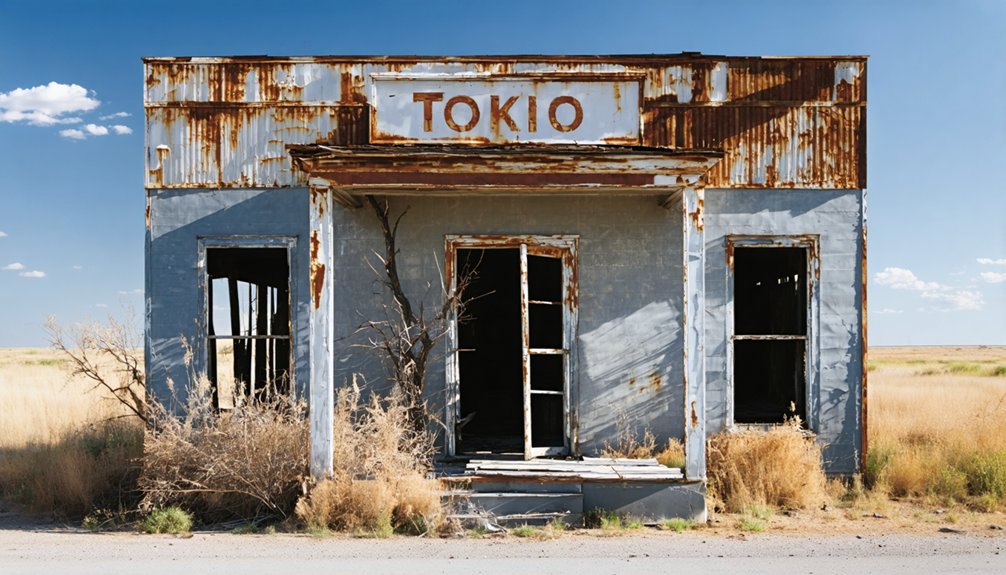

You’ll find Tokio, Texas about 17 miles west of Brownfield, established in 1908 and named after Japan’s capital by Mrs. H. L. Ware, who became its first postmistress. The town relocated a mile south in 1928 to stay connected with U.S. Highway 380, reaching its peak of 125 residents in the 1940s with three businesses. By 2000, only 24 residents remained, leaving weathered buildings to tell tales of this once-thriving farming community.

Key Takeaways

- Tokio, Texas began in 1908 and reached its peak population of 125 residents in the 1940s before declining to ghost town status.

- The town relocated one mile south in 1928 to maintain access to U.S. Highway 380, which initially helped sustain its economy.

- Agricultural activities, including cotton farming and livestock, formed the economic foundation before the community’s eventual decline.

- By 2000, Tokio’s population had dwindled to just 24 residents, with most businesses closed and structures abandoned.

- Today, Tokio stands as a semi-abandoned ghost town with deteriorating buildings that attract history enthusiasts and photographers.

Origins and Early Settlement

As settlers pushed into western Terry County in the early 1900s, the small farming community of Tokio emerged around 1908 near what would become the intersection of U.S. Highway 82/380 and a local road.

The town’s name came from Mrs. H. L. Ware, who drew inspiration from Japan’s capital city, though no direct cultural influences from Japan ever took root in the settlement.

Early pioneers were drawn to the area’s agricultural potential, with Mrs. Ware establishing herself as a community leader when she became the first postmistress in 1912.

Agricultural promise brought settlers to Tokio, where Mrs. Ware’s appointment as postmistress in 1912 marked her community leadership.

The post office served as a crucial communication hub for the growing settlement.

While farming remained the primary occupation, the discovery of oil and gas deposits nearby would soon attract additional settlers to this remote West Texas outpost.

The town later experienced modest growth, reaching a population of 25 residents by 1910.

The Early Settlers of Terry publication documents the determination of these pioneering families who established the foundation of the community.

Life in Tokio’s Heyday

The small farming community of Tokio reached its peak in the 1940s, with a population of 125 residents and three active businesses serving the area.

You’d have found a tight-knit community centered around the local post office and school, where families gathered to exchange news and maintain their cultural heritage.

For accurate navigation to information about various places named Tokio, residents and visitors relied on disambiguation pages to distinguish this Texas town from other similarly named locations.

The town’s strategic location at the intersection of U.S. Highway 82/380 connected you to neighboring settlements, while the surrounding oil and gas fields provided economic opportunities alongside traditional farming.

Much like the town of Best, which saw its population plummet from 3,500 to 300 between 1925 and 1945, Tokio experienced its own dramatic decline.

Community dynamics shifted dramatically in 1941 when the school closed due to district consolidation.

By the 1950s, Tokio’s population had dropped to sixty residents, though this level held steady for several decades.

The post office remained a crucial hub, preserving the town’s identity until its eventual decline in the 1990s.

The Town’s Strategic Relocation

You’ll find Tokio’s most crucial moment came in 1928 when the town physically relocated one mile south to maintain its essential connection with U.S. Highway 380.

The strategic move required significant infrastructure changes, including the relocation of the post office and other essential services to serve the town’s roughly 125 residents. Much like Cedar Mills, Texas facing decline when railways bypassed it, these communities often had to adapt to survive near vital transportation routes. This situation echoed the economic shifts that transformed other Texas towns like Thurber, where the transition to oil-burning locomotives devastated local coal industries.

While the relocation temporarily preserved Tokio’s economic viability through improved transportation access, you’d later see this advantage wasn’t enough to prevent the town’s eventual decline to just 24 residents by 2000.

Highway Access Benefits

When Highway 380 shifted its route in 1928, Tokio’s leaders made a strategic decision to relocate the entire town one mile south, positioning it directly along this essential transportation artery. This move dramatically improved the town’s economic connectivity, giving residents direct access to one of West Texas’s important transportation infrastructure corridors.

You’ll find that this new location provided multiple benefits for Tokio’s community. The highway proximity enhanced the transport of goods and services, increased the town’s visibility to travelers, and strengthened links to larger regional markets.

Local businesses flourished from passing trade, while residents enjoyed improved mail service and mobility. The strategic placement also created opportunities for new enterprises catering to motorists, helping Tokio maintain its population through the 1940s. Similar to Bartonsite’s relocation to Abernathy, moving an entire town proved to be a viable strategy for survival in early Texas. The town’s post office since 1912 became an important anchor for the community after the move.

Infrastructure Modernization Challenges

Despite Tokio’s strategic relocation to Highway 380 in 1928, significant infrastructure modernization challenges plagued the town’s development throughout its later years.

You’ll find that limited infrastructure funding and the absence of municipal governance made it nearly impossible to implement effective modernization strategies. The town’s underground mining track, stretching 14 miles beneath the surface, presented unique maintenance challenges. The town’s small population couldn’t generate sufficient tax revenue for essential upgrades. The lack of public-private partnerships severely limited potential infrastructure development opportunities.

The town’s isolated rural setting, coupled with flooding risks and challenging terrain, further complicated infrastructure improvements.

Without formal planning codes or zoning regulations, coordinating with state agencies and private investors became increasingly difficult. The lack of administrative structure left Tokio unable to secure permits or meet modern building standards.

These barriers ultimately contributed to the town’s decline, as it couldn’t adapt to changing technological and environmental demands of the modern era.

Community Impact Assessment

The strategic relocation of Tokio to Highway 380 in 1928 marked a pivotal moment that profoundly reshaped the town’s demographic destiny.

While the move was intended to maintain essential transportation connections, you’ll find it actually accelerated the community’s decline, testing its resilience in unexpected ways.

Despite initial hopes, the relocation didn’t preserve Tokio’s social cohesion or economic vitality.

You can trace the town’s transformation from a thriving community of 125 residents in the 1940s to its current ghost town status.

By 2000, only 24 residents remained, and the once-bustling town lost its post office and most businesses.

Today, the 1911 schoolhouse stands as a silent reminder of Tokio’s former vibrancy, while the absence of new development reflects the broader pattern of rural depopulation across Texas’s Southern Plains.

Economic Pillars and Community Growth

You’ll find Tokio’s economic roots firmly planted in agriculture, with the surrounding Terry County land providing fertile ground for farming operations that supported the town’s early growth.

The discovery of oil and gas fields in the region brought additional economic opportunities, though these served more as supplemental income rather than replacing farming as the primary economic driver.

Agriculture Drives Early Growth

Farming formed the bedrock of Tokio’s early development when settlers established the community around 1908 in western Terry County.

You’ll find the town’s agricultural roots reflected in its crop diversity, which included cotton, grains, and hay suited to the semi-arid climate. Local families supplemented their income through livestock integration, raising cattle and sheep on the surrounding rangeland.

This agricultural foundation proved strong enough to sustain community growth, supporting the establishment of a post office in 1912 and a school that served local farming families until 1941.

You can trace Tokio’s peak prosperity to its farming success, which helped maintain a population of 125 residents through the 1940s. The construction of US Highway 380 in 1928 connected farmers to broader markets, though harsh conditions and economic pressures would later challenge their way of life.

Oil Industry Boosts Population

During the 1920s, Tokio’s economic landscape shifted dramatically when oil exploration expanded into Terry County, bringing an influx of workers and their families to the region.

You’d have seen the familiar pattern that swept across Texas: oil migration transformed quiet agricultural communities into bustling hubs of activity. As drilling operations intensified, secondary industries sprouted up to support the growing population boom.

Just as in other Texas boomtowns like Kilgore and Longview, you’d have witnessed rapid development of community infrastructure. New schools, stores, and service businesses emerged to meet the needs of oil field workers and their families.

This growth mirrored the broader Texas experience, where oil discoveries reshaped local economies and prompted significant demographic changes, though many such towns later faced decline when production waned.

The Path to Decline

While many small Texas towns faced economic challenges in the 20th century, Tokio’s path to decline stemmed from a perfect storm of geographic isolation and missed opportunities.

You’ll find the town’s economic trends traced back to its unfortunate location – 17 miles west of Brownfield without essential railroad access that powered growth in neighboring communities.

Population changes tell the story dramatically: from a peak of 125 residents in the 1940s, you’d see the numbers dwindle to just 24 by 2000.

The town’s isolation meant it couldn’t attract sustainable industry beyond farming, and even the nearby oil and gas fields couldn’t generate lasting prosperity.

Without infrastructure investment or business diversification, Tokio couldn’t compete with rail-connected towns, leading to closed businesses and steady outmigration that transformed it into a semi-abandoned community.

Modern-Day Ghost Town Legacy

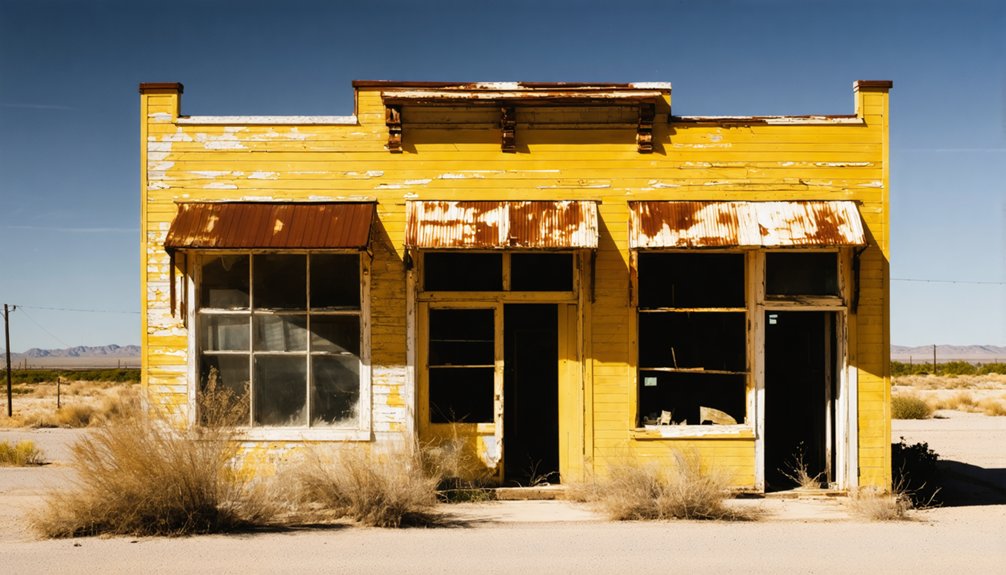

Today, you’ll find Tokio standing as a haunting reminder of Texas’s rural transformation, with its abandoned buildings and quiet streets telling the story of a once-vibrant community.

While ghost town preservation efforts remain minimal, local historians and enthusiasts document the site’s deteriorating structures through photographs and records. You can still explore several standing buildings, though many lack roofs and show signs of neglect.

Weathered buildings stand as silent witnesses, while dedicated locals work to preserve Tokio’s fading history through careful documentation.

The town’s historical significance lives on through local legends and oral histories, offering glimpses into early 20th-century rural life.

While tourism infrastructure is limited, you’ll join other history buffs and photographers who make their way to this atmospheric site.

Despite its abandoned status, Tokio continues to captivate those seeking to understand Texas’s changing landscape and the stories of communities that time left behind.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Original Buildings When Tokio Relocated in 1928?

Like weathered tombstones of progress, you’ll find most buildings weren’t moved during the 1928 relocation. They were left behind to decay naturally, though the school building survives as a historical preservation landmark.

Are There Any Surviving Descendants of Mrs. H. L. Ware Living Nearby?

You won’t find definitive records of Ware family descendants in the area today. Local history archives and genealogical databases don’t confirm if any of Mrs. H. L. Ware’s relatives still live nearby.

Did Tokio Ever Have a Railroad Connection During Its Existence?

No, you won’t find any railroad history in Terry County’s Tokio. The town’s transportation impact centered solely on Highway 380, which actually caused its relocation in 1928.

What Specific Crops Were Predominantly Grown by Tokio’s Farming Community?

You’ll find that rice was Tokio’s dominant crop, not cotton production. Japanese farmers applied their advanced agriculture techniques to rice cultivation, while some later diversified into vegetable and fruit farming.

Were There Any Notable Crimes or Major Incidents in Tokio’s History?

You won’t find any documented crime incidents in the historical records of this small settlement. What’s interesting is how peaceful its decline was compared to other ghost towns.

References

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/tokio-tx-terry-county

- https://www.texasescapes.com/CentralTexasTownsNorth/TokioTexas/TokioTexas.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Tokio

- https://melindagreenharvey.com/tag/tokio-texas/

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TexasGhostTowns/TokioTexas/TokioTexas.htm

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/tokio-tx-mclennan-county

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hgCxNIlUi8Y

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokio

- https://www.texasstandard.org/stories/best-texas-the-ghost-town-with-the-worst-reputation/