Ancient Native American towns reveal sophisticated urban planning that predates European contact. You’ll find engineering marvels like Cahokia’s massive earthen mounds, cliff dwellings carved into sandstone, and multi-story pueblos—all built without metal tools. These weren’t isolated settlements but thriving hubs in vast trade networks spanning thousands of miles. Despite colonization pressures, communities like Oraibi (established around 1100 AD) maintained cultural continuity for centuries. The archaeological evidence tells a story of innovation and resilience rarely acknowledged in mainstream history.

Key Takeaways

- Cahokia was North America’s largest pre-Columbian metropolis, housing up to 20,000 residents across five square miles with 120 earthen mounds.

- Oraibi on the Hopi Reservation dates to before 1100 AD, making it America’s oldest continuously inhabited settlement.

- Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings featured sophisticated architecture integrating defensive elements, communal spaces, and ceremonial kivas.

- Extensive trade networks connected Native American towns, facilitating exchange of goods, cultural practices, and technologies over vast distances.

- Archaeological evidence reveals ancient Native American communities maintained cultural continuity despite colonization through adaptive traditional practices.

The Living Legacy of Oraibi: America’s Oldest Continuously Inhabited Settlement

Nestled atop the Third Mesa of the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, Oraibi stands as perhaps the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in the United States, with origins dating back to before 1100 AD.

Tree-ring dating confirms occupation before 1358 AD, with probable founding during the 12th or 13th century.

You’ll find that Oraibi’s settlement evolution accelerated during the great drought of 1276-1299, as surrounding populations consolidated here.

The village has witnessed nearly a millennium of history, from first Spanish contact in 1540 to the cultural divisions of 1906.

Though its population has dwindled from thousands to fewer than 100 today, Hopi traditions endure despite centuries of external pressure.

This settlement predates many well-known Spanish colonial cities like El Paso del Norte, which was officially founded over 500 years later in 1659.

The community split between traditionalists, who founded Hotevilla, and progressives, who established Kykotsmovi Village, reflects the ongoing tension between preservation and adaptation.

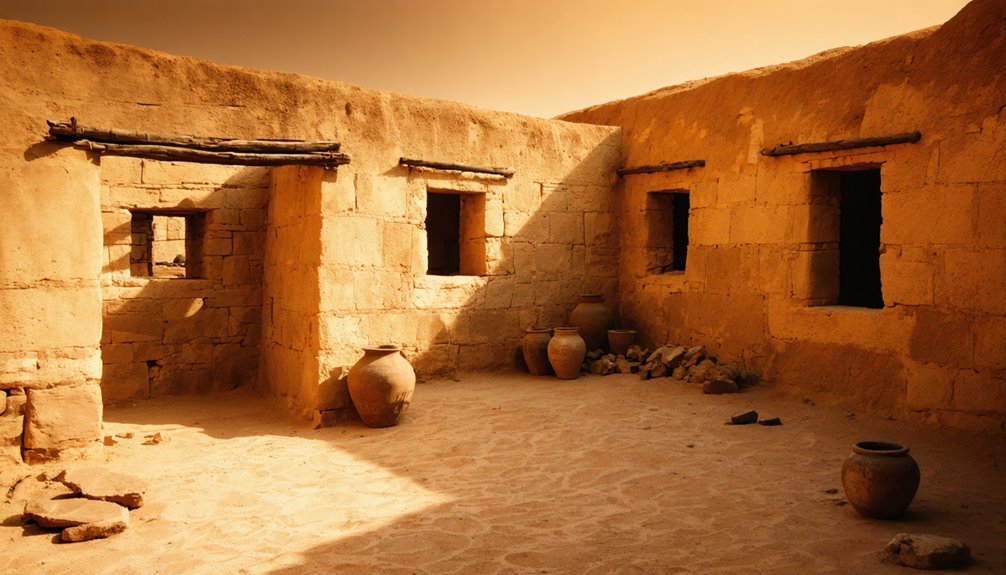

The village’s distinctive adobe buildings exemplify traditional Hopi architectural techniques perfectly adapted to the harsh desert environment.

Cahokia: The Forgotten Metropolis of Pre-Columbian North America

You’ll be astonished to learn that Cahokia once rivaled contemporary European cities in size, housing up to 20,000 residents across more than five square miles of meticulously planned urban space.

The city’s massive infrastructure featured approximately 120 earthen mounds, including the imposing Monks Mound—the third largest pyramid in the Americas—and a grand plaza equivalent to 35 football fields.

Evidence suggests that the establishment of this remarkable city around 1050 CE may have been influenced by celestial events like the supernova of 1054.

Cahokia’s influence extended far beyond its physical boundaries through extensive trade networks that circulated exotic materials like copper, marine shells, and specialized crafts throughout eastern North America.

Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1982, Cahokia represents one of the most significant pre-Columbian archaeological sites in North America.

Massive Scale and Infrastructure

Cahokia emerged as North America’s first true metropolis, dwarfing contemporary Native settlements and rivaling many European urban centers of the same period. With 10,000-20,000 inhabitants spread across 4,000+ acres, its urban density reflects sophisticated social organization unmatched north of Mexico.

The city’s infrastructure featured 120 earthen mounds, including the massive Monks Mound standing 100 feet tall on a 15-acre base. These structures held ceremonial significance as platforms for rituals, elite burials, and public gatherings. This remarkable site has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1982.

The central precinct displayed deliberate urban planning, with a grand plaza surrounding residential areas and defensive palisades extending three kilometers. Excavations have revealed that the residents relied heavily on corn agriculture for sustenance, which supported the dense population concentration.

Cahokia’s builders accomplished this monumental construction using only earth and basic tools—evidence of their capacity to mobilize labor for ambitious engineering projects without modern technology or written language.

Cultural and Trade Impact

Beyond its physical grandeur, the cultural and economic footprint of America’s first true metropolis extended far beyond its earthen walls.

You’ll find Cahokia’s influence evident across the Mississippi Valley, where communities emulated its distinctive mound architecture and religious practices.

The city established extensive trade routes connecting regions from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast. The site’s importance as a cultural and religious center of the Mississippian tradition facilitated widespread exchange of ideas and practices throughout the region.

These networks facilitated cultural exchange through the movement of copper, marine shells, mica, and ceremonial objects.

Cahokian pottery styles and iconography—featuring the distinctive Birdman and hand-eye motifs—spread throughout the southeast, creating a shared visual language among distant communities.

The traditional game of chunkey became popular during festivals and spread to surrounding areas as part of Cahokia’s cultural influence.

This sophisticated web of commerce and cultural diffusion challenges outdated notions about pre-European Native societies, revealing instead a complex civilization whose economic and spiritual influence shaped an entire continent’s indigenous landscape.

Sacred Architecture: Cliff Dwellings and Pueblos of the Southwest

You’ll find the Ancestral Puebloans’ cliff dwellings strategically positioned in sandstone alcoves, offering natural protection from both environmental threats and potential raiders.

These defensive “sky cities,” built between 1100-1300 CE across the Four Corners region, integrated thick stone walls with sacred circular kivas to balance security and ceremonial needs. The communities thrived on settled agriculture while supplementing their diet through hunting and gathering practices.

The ingenious architectural adaptation to cliff faces created multi-story complexes that housed entire communities while maintaining access to agricultural lands through carefully designed pathways and ladders. These impressive structures, like those at Bandelier National Monument, allowed visitors to experience authentic dwelling access using ladders similar to those used by original inhabitants.

Defensive Sky Cities

Perched high among the cliff faces and mesas of the American Southwest, defensive sky cities represent some of the most remarkable architectural achievements of Native American cultures.

You’ll find these structures strategically positioned to maximize visibility of approaching threats, with access limited to narrow ledges or hand-carved steps that could be easily defended.

The architectural design reveals sophisticated defensive strategies: small windows, roof entrances accessed by removable ladders, and layouts that funneled attackers into confined spaces.

Built atop mesas or into cliff recesses, these communities withstood both environmental challenges and human conflicts.

When Spanish expeditions arrived in the late 16th century, pueblos like Acoma utilized these defensive positions to resist invasion and maintain cultural continuity despite colonization pressures.

Archaeological evidence confirms continuous habitation of these sites since approximately 1100 CE.

Sandstone Sacred Spaces

While defensive fortifications dominated many ancient Native American settlements, the sacred architecture of cliff dwellings and pueblos across the Southwest reveals an equally sophisticated understanding of both spiritual and practical design principles.

You’ll find these sandstone marvels nestled within the Four Corners region, where Ancestral Puebloans constructed elaborate complexes between 1150-1300 CE. Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace exemplifies architectural symbolism with its 150 rooms and 20+ ceremonial kivas.

These structures weren’t merely shelters—they served as community centers where spiritual practices flourished.

The thick-walled constructions utilized local materials: stone, mud mortar, and wooden support beams.

Modern cliff conservation efforts focus on sites like Keet Seel at Navajo National Monument, preserving these sacred spaces against erosion and vandalism while honoring their continued significance to indigenous communities.

Early Innovation: The Remarkable Engineering of Mound-Building Societies

Long before the arrival of modern tools or technology, ancient Native American societies demonstrated remarkable engineering prowess through their ambitious mound-building projects.

You’ll find their mound construction relied entirely on manual labor, using basket-carrying methods to transport materials that would form structures lasting millennia.

Their soil engineering was surprisingly sophisticated—mixing different soil types created composite materials comparable to ancient Roman concrete.

By carefully layering and fire-hardening clay, these societies produced structures that have withstood thousands of years of environmental exposure.

Ancient engineers transformed simple clay into weather-resistant monuments through strategic layering and fire-hardening techniques.

These projects required complex social organization, with leaders coordinating hundreds or thousands of laborers across generations.

The resulting architectural forms—from flat-topped pyramids to crescent-shaped ridges—served as temples, burial sites, and ceremonial spaces, reflecting these communities’ advanced understanding of materials science unknown even to modern engineers.

Trade Networks and Cultural Exchange Among Ancient Native American Communities

Beyond their remarkable engineering achievements, ancient Native American societies developed intricate trade networks that connected communities across vast distances.

At strategic hubs like Cahokia, The Dalles-Celilo, and Taos Pueblo, you’d find bustling centers where diverse cultures converged. These economic exchanges weren’t merely transactional—they represented sophisticated systems utilizing established trade routes along waterways and natural pathways.

Traders exchanged millions of pounds of salmon, turquoise, obsidian, and countless other commodities using canoes, dog-travois, and later horses. The discovery of Ramah chert artifacts thousands of miles from their origin reveals the extraordinary scope of these networks.

To facilitate communication, traders developed shared languages like Chinook, while employing bartering, gifting, and even gambling as exchange methods, creating dynamic systems that distributed wealth and knowledge throughout pre-colonial North America.

Resilience Through Colonization: How Native Towns Adapted and Survived

Following the devastating impact of European colonization, Native American communities demonstrated extraordinary resilience and adaptation through sophisticated survival strategies.

You’ll find they developed multi-layered adaptive strategies including strategic raiding, alliance formation, and cultural preservation tactics that enabled their survival against overwhelming forces.

Apache groups mastered horse-based mobility for swift raids while forming necessary alliances with other tribes to consolidate defenses.

Apache warriors leveraged equestrian mobility for lightning raids, strategically partnering with neighboring tribes for mutual protection.

Communities preserved cultural integrity by ingeniously incorporating traditional practices into imposed Christian frameworks, effectively hiding in plain sight.

Their economic adaptations included developing alternative trade enterprises while maintaining traditional subsistence practices despite land expropriation.

This cultural resilience manifested through political negotiations that secured small land tracts and through resistance to federal governance interference, ultimately enabling partial sovereignty despite generations of assimilation pressure.

Preserving Ancient Wisdom: Cultural Continuity in Historic Native American Towns

While Native American communities fought physical battles for survival during colonization, they simultaneously waged a more nuanced campaign to preserve their ancestral knowledge systems across generations.

You’ll find that oral traditions formed the backbone of this preservation, transmitting complex ecological wisdom and spiritual beliefs through storytelling that incorporated cyclical time concepts and active listener participation.

Elder mentorship systems functioned as living libraries, with revered knowledge-keepers guiding apprenticeships and rites of passage to maintain cultural continuity.

This intergenerational dialogue manifested through artistic expressions—pottery, beadwork, and ceremonial performances—that embedded tribal symbolism and philosophy.

Land-based education reinforced connection to ancestral territories through experiential learning of traditional plant uses and sustainable farming.

Today, these preservation methods have evolved to include collaborative ethnography and digital archives that safeguard ancient wisdom for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Native American Towns Govern Themselves Before European Contact?

You’ll find Native American towns governed through clan-based tribal governance, with leadership roles established through inheritance or merit. Their systems emphasized consensus decision-making, customary law, and territorial autonomy rather than centralized authority.

What Technologies Did Ancient Native Americans Use for Urban Planning?

You’ll find Native Americans employed sophisticated irrigation canals, terraced farming, earthquake-resistant stone architecture, grid-pattern layouts, and specialized agricultural techniques using local construction materials like adobe, terracotta, and stone for sustainable urban centers.

How Accurate Are Population Estimates for Pre-Columbian Native Towns?

Like sifting through sand for gold, pre-Columbian population estimates remain highly variable. You’ll find archaeological evidence yields wide-ranging figures, as radiocarbon dating and settlement patterns reveal complex population dynamics but lack precision.

What Seasonal Ceremonies Marked the Calendar in Ancient Native Settlements?

You’d find major agricultural Harvest Festivals like Creek Busk ceremonies, Winter Solstice observances, lunar-based rituals, and ceremonies aligned with resource cycles marking Native American settlement calendars across different tribes.

How Did Climate Changes Affect Native American Settlement Patterns?

You’d think climate change is modern, yet Native Americans constantly practiced climate adaptation through settlement migration, relocating from droughts, abandoning Mesa Verde during 13th century cooling, and clustering around reliable water sources.

References

- https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/america-s-earliest-cities-were-native-american-spanish

- https://www.thecollector.com/the-5-oldest-native-american-towns-in-the-united-states/

- https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/essays/cahokia-pre-columbian-american-city

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Columbian_era

- https://www.hnn.us/article/183147

- https://guides.loc.gov/native-american-spaces/cartographic-resources/indian-sites

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-ancientcities/

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/timeline-of-native-american-cultures.htm

- https://ehillerman.unm.edu/3012

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oraibi