Several Civil War ghost towns remain abandoned across America today, including Randolph, Tennessee (destroyed by Union forces) and Old Cahawba, Alabama (former state capital and Confederate prison). You’ll find remnants of Virginia City, Nevada with its preserved architecture, while Harrisburg, Utah shows how natural disasters compounded war devastation. These forgotten communities tell powerful stories of military destruction, economic collapse, and the permanent reshaping of America’s landscape through deliberate fire campaigns and resource requisition.

Key Takeaways

- Randolph, Tennessee was destroyed twice during the Civil War and became abandoned with fewer than 200 residents by 1900.

- Old Cahawba, Alabama, the first state capital, was converted to a Union prison camp before declining after the war.

- Harrisburg, Utah experienced complete abandonment by 1892 after suffering from Virgin River floods and multiple crises.

- Virginia City, Nevada remains as a preserved ghost town with Civil War-era architecture and cultural significance.

- Numerous towns collapsed when railroads were systematically destroyed using techniques like “Sherman’s Neckties” during the war.

Randolph, Tennessee: Union Destruction and Abandonment

Once a formidable commercial rival to Memphis, Randolph, Tennessee occupied a strategically advantageous position on the second Chickasaw Bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. This elevation made it perfect for Confederate fortifications—Forts Randolph and Wright—constructed in 1861 using slave labor.

When Confederate guerrillas fired upon the unarmed steamboat Eugene in September 1862, General William T. Sherman ordered Randolph’s complete destruction in retaliation. Union forces burned approximately 97 businesses and homes, sparing only one church and a single dwelling.

Federal troops torched the town again in 1865, devastating what remained of its infrastructure. The town’s decline was exacerbated by continuous river erosion that undermined its physical foundations. This destruction dramatically altered Randolph’s history. Both forts had already been abandoned by the Confederates in the summer of 1862, relocating men and artillery to other strategic locations. By 1900, the population remained below 200, with only a handful of dilapidated structures standing.

An 1886 fire destroyed most surviving buildings, cementing Randolph’s legacy as a casualty of Civil War retribution.

Old Cahawba, Alabama: From Confederate Prison to Ghost Town

While Alabama’s first state capital now stands as a ghost town, Old Cahawba‘s journey from prosperity to abandonment encapsulates the tumultuous impact of the Civil War on Southern communities.

Once situated at the confluence of two rivers, Cahawba’s heritage was defined by cotton wealth that made Dallas County Alabama’s richest by 1860. The town was carefully designed in a grid layout similar to Philadelphia, with streets named after trees.

At the meeting of powerful waters, Cahawba built its fortune on white gold, transforming Dallas County into Alabama’s crown jewel.

During the war, Confederate forces converted a warehouse into Castle Morgan, holding over 3,000 Union prisoners despite being designed for 500. Conditions were extremely harsh, with unsanitary facilities, widespread disease, and limited resources contributing to nearly 150 deaths. This Civil War legacy includes the historic prisoner exchange negotiated at the Crocheron Mansion—ironically occurring the same day as Lee’s surrender.

After losing its county seat status to Selma in 1866, Cahawba’s population plummeted.

The abandoned courthouse became the center of Reconstruction politics, where freed slaves organized politically, with Jeremiah Haralson rising from slavery to Congress.

Elko Tract, Virginia: The Phantom Military Deception

Unlike Old Cahawba’s transformation from Confederate prison to ghost town, Elko Tract in Virginia represents a deliberate phantom—a military deception that evolved into an abandoned landscape with a complicated racial history.

In 1942-1943, the U.S. Army seized 2,220 acres of farmland to construct a detailed decoy of Richmond Army Air Base. The 936th Camouflage Battalion built streets, runways, and plywood planes designed to mislead Axis bombers during night raids.

Though never tested by enemy fire, this $500,000 military deception included thorough infrastructure that remained visible for decades after the war. The deception operation directly impacted over 40 farms whose land was taken for the military project. Today, much of the site has been repurposed, with a semiconductor plant occupying significant portions of the former ghost town.

Post-war plans to convert Elko into a segregated mental hospital for African Americans were abandoned amid white opposition.

Batsto Village: Civil War Iron Production Legacy

When you visit Batsto Village today, you’ll encounter a striking contradiction – while the ironworks had ceased industrial operations prior to the Civil War, historical records reveal a significant factual misconception about the site’s wartime role.

The Richards family had already dismantled the furnace in 1855, with both iron production and glassworks operations having completely shut down before the conflict erupted between Union and Confederate forces.

This preserved industrial village now stands as an extraordinary time capsule of America’s early manufacturing era, though its actual contribution to the Civil War existed only in its absence rather than in any material production for military purposes. Following decades of decline, Joseph Wharton acquired the property in 1876 and focused on revitalizing the village through agricultural development rather than returning to its industrial roots. The village’s original iron works had once supplied the Continental Army during America’s fight for independence, long before its Civil War era decline.

Ironworks Sustained Union

During the American Civil War, Batsto Village’s ironworks heritage remained integral to Union military success, despite the facility’s decline in iron production by that era. The ironworks significance had begun shifting by the 1850s, with traditional bog iron operations ceasing in 1855 as more competitive sources emerged nationwide.

Though Batsto’s furnace had been dismantled before the Civil War began, its industrial evolution toward glassmaking helped sustain the community while its earlier infrastructure contributions—particularly the cast iron pipes supplied to major Northern cities like New York—continued supporting Union logistics. The Batsto Glass Works established in the 1840s produced window glass until its closing in the 1860s.

These waterworks systems, constructed from Batsto materials, proved essential to maintaining urban centers that coordinated wartime supply chains and troop movements.

You can still witness this evolutionary change at the preserved site today, where remnants showcase America’s early industrial freedom from European manufacturing dependence. The site features Wharton’s restoration work from 1870, which helped preserve this vital piece of American industrial history.

Hidden Historical Preservation

The preservation of Batsto Village’s historical significance stands as a tribute to America’s early industrial ingenuity, revealing layers of history that might otherwise have vanished.

When you explore this meticulously restored site today, you’ll discover hidden artifacts catalogued by Stockton University’s special collections—including glass bottles from the 1846 glassworks and documentation of industrial operations spanning nearly a century.

The Batsto Citizens Committee has rescued forgotten narratives of this once-thriving community, where industrial workers were exempted from military service due to their essential production role.

Though the village experienced dramatic decline when bog iron markets collapsed in the 1840s—culminating in the furnace’s 1855 dismantling and devastating fires—preservation efforts have guaranteed this unique chapter of American industrial heritage remains accessible rather than lost to time.

Harrisburg, Utah: Natural Disasters and Post-War Exodus

Nestled at the confluence of the Virgin River with Quail and Cottonwood creeks, Harrisburg emerged in 1859 as a hopeful settlement established by Moses Harris and Mormon immigrant families seeking agricultural prosperity in Washington County, Utah.

Despite their determination, the community’s flood vulnerability became catastrophically apparent in 1862 when the Virgin River submerged the original settlement, forcing immediate relocation.

Survivors rebuilt along Quail Creek, renaming the settlement Harrisburg and demonstrating remarkable settlement resilience through construction of stone cottages and the Adams House between 1862-1865.

However, compounding crises—grasshopper plagues, continued flooding, and Native American conflicts—ultimately overwhelmed the community.

By 1869, most residents had departed, with complete abandonment by 1892.

Today, only stone ruins remain approximately 130 miles from Las Vegas in the Red Cliffs Conservation Area.

The Role of Railroad Destruction in Civil War Town Abandonment

While many abandoned Civil War towns fell victim to natural disasters and changing economic conditions, systematic destruction of railroad infrastructure served as perhaps the most devastating catalyst for permanent town abandonment throughout the conflict.

Union forces employed sophisticated railroad sabotage techniques, creating “Sherman’s Neckties” by heating and twisting rails around trees, while Confederate troops implemented scorched earth tactics during retreats. This deliberate destruction triggered immediate economic collapse in rail-dependent communities, severing essential supply chains and communication networks.

The strategic decimation of railroads doomed countless towns to extinction, their economic arteries deliberately severed by both armies.

You can still witness the legacy of this strategy in ghost towns across the South, where communities never recovered from the severed lifelines. The psychological impact was equally devastating—residents fled as isolation and uncertainty mounted.

When both sides targeted rail infrastructure, they weren’t just attacking transportation; they were eliminating the very foundation upon which town survival depended.

Fire’s Devastating Impact on Post-War Communities

Throughout the aftermath of the Civil War, deliberate fire campaigns emerged as perhaps the most visually devastating weapon against Southern communities, leaving an indelible mark that permanently altered the landscape of American townships.

You’ll find the most extreme examples in places like Eunice, Arkansas and Randolph, Tennessee, where fire damage was so complete that recovery became impossible. Randolph faced destruction twice, with Sherman’s forces leaving just one house standing in 1862, before soldiers returned to finish the job in 1865.

In Darien, Mississippi, even brick foundations couldn’t support community recovery after the entire business district burned on June 11, 1863. Similarly, Hampton, Virginia lost over 130 businesses and homes, while Chambersburg, Pennsylvania suffered the destruction of 500 structures, effectively eliminating their economic infrastructure and preventing meaningful post-war rebuilding.

Preserved Civil War Ghost Towns You Can Visit Today

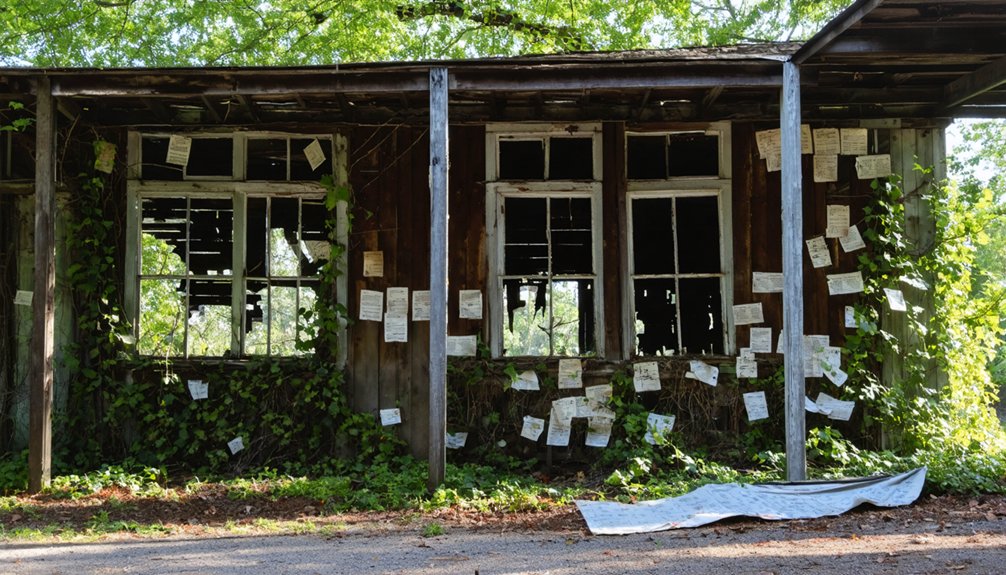

Despite the devastating aftermath of the Civil War, several abandoned towns have survived the passage of time as preserved historical sites, offering visitors a tangible connection to America’s tumultuous past.

Cahaba, Alabama’s first capital, stands as a symbol of historic preservation efforts, with its haunting ruins and archaeological remnants from its days as a Civil War prison camp. The site’s ghostly lore features tales of 19th-century children, slaves, and prisoners.

Virginia City, Nevada, though primarily known for the Comstock Lode silver discovery, retains Civil War-era architecture and cultural significance.

You’ll walk wooden sidewalks past meticulously maintained buildings that witnessed the nation’s divided years. These preserved communities balance educational value with the freedom to explore America’s complex heritage at your own pace.

How Military Resource Requisition Led to Town Collapse

During the Civil War, military resource requisition devastated countless American communities, transforming once-thriving towns into abandoned shells. As Confederate forces commandeered railroads and transportation routes, towns lost essential supply lines, initiating irreversible economic decline.

You would have witnessed the systematic dismantling of local infrastructure—factories repurposed, bridges destroyed, and homes abandoned. Resource scarcity became endemic as armies seized food, livestock, and raw materials for wartime operations.

With able-bodied men conscripted and agricultural production redirected to military needs, communities spiraled into poverty. Towns situated along strategic corridors suffered most severely, their industries collapsing without access to markets or materials.

This economic strangulation often proved permanent, as post-war reconstruction efforts prioritized cities with remaining infrastructure. The abandoned ruins you might encounter today stand as silent testimonies to this calculated military disruption.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Residents Attempt to Rebuild Abandoned Towns After the Civil War?

Yes, you’ll find many residents attempted rebuilding efforts after the Civil War, though economic challenges often thwarted their plans as floods, destroyed infrastructure, and shifting industries complicated recovery.

How Did Former Slaves Adapt After Civil War Towns Were Abandoned?

Envision this: liberty on paper, shackles in practice. You’ll find freedmen communities formed on town outskirts, with economic adaptations including sharecropping, tenant farming, establishing independent churches, and migrating to urban centers seeking opportunity.

Were Any Civil War Ghost Towns Later Reoccupied for Different Purposes?

You’ll find numerous Civil War ghost towns repurposed for historical preservation and ghost town tourism, while others transformed into military installations, nuclear research facilities, or conservation areas within national forests.

What Artifacts Remain Most Commonly in Civil War Abandoned Settlements?

While many Civil War relics have been looted over time, you’ll commonly find structural remains like chimney stacks, foundations, and earthworks, alongside historical artifacts including military items, household objects, and industrial implements in these abandoned settlements.

How Did Native Americans Interact With These Abandoned Civil War Towns?

Native Americans reclaimed abandoned Civil War towns as hunting grounds and occasionally repurposed structures, enabling cultural preservation while establishing new relationships with sites of historical significance where their ancestors once lived freely.

References

- https://www.loveexploring.com/gallerylist/131658/abandoned-in-the-usa-92-places-left-to-rot

- https://www.mentalfloss.com/geography/american-ghost-towns-can-still-walk-through

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.blueridgeoutdoors.com/go-outside/southern-ghost-towns/

- https://www.tnmagazine.org/19-ghost-towns-in-tennessee-that-are-not-underwater/

- https://www.visittheusa.com/experience/5-us-ghost-towns-you-must-see

- https://devblog.batchgeo.com/ghost-towns/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XCkwcKi5Czg

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNsGNbsIQSc

- https://www.mythfolks.com/haunted-us-ghost-towns