Across America, you’ll find numerous submerged communities beneath reservoir waters—victims of 20th-century dam projects. In Appalachia, towns like Gad, West Virginia rest under Summersville Lake, while Alabama’s Lake Martin covers Kowaliga, a freed slave settlement. Western states harbor mining towns like Kennett beneath Shasta Lake, and Indigenous sacred sites like Celilo Falls disappeared entirely. During droughts, these watery ghost towns occasionally reveal their foundations, offering fleeting glimpses into America’s sacrificed past.

Key Takeaways

- Gad, West Virginia lies beneath Summersville Lake, with foundations visible during periodic drainings.

- Loyston, Tennessee was sacrificed for TVA dam projects, preserving sociological surveys of pre-flood community life.

- Old Bluffton, Texas emerges from Lake Buchanan during droughts, revealing tombstones and a cotton gin.

- St. Thomas, Nevada was submerged when Lake Mead filled in 1938, occasionally resurfacing during severe drought conditions.

- Kowaliga, an Alabama town founded by freed slaves, disappeared beneath Lake Martin in 1926, erasing significant Black heritage.

The Drowned Valleys of Appalachia

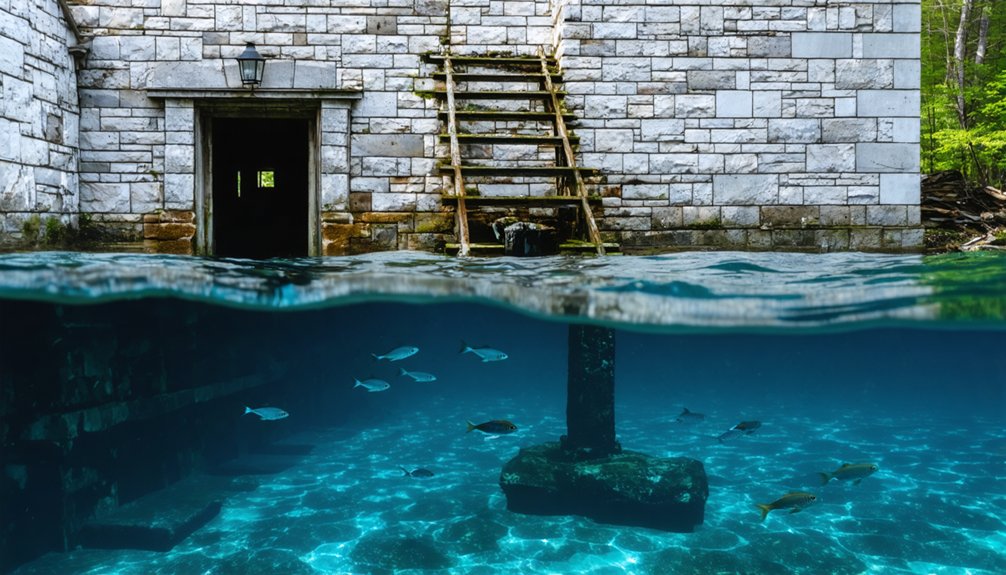

While the picturesque ridges of Appalachia captivate tourists today, beneath several of the region’s largest lakes lie the remnants of once-thriving communities, systematically submerged during the mid-twentieth century‘s infrastructure boom.

You’ll find drowned histories in places like Gad, West Virginia, now beneath Summersville Lake, where foundations and rock carvings resurface during decennial drainings.

At Lake Jocassee, divers report eerie “forest walks” among submerged structures, including the preserved Attakulla Lodge.

Beneath Lake Jocassee’s surface, divers glide through ghostly forests, where Attakulla Lodge stands in silent testimony to the drowned world.

The TVA’s dam-building campaign claimed numerous towns like Loyston, Tennessee, where detailed sociological surveys preserve what water conceals.

These submerged legacies tell stories of sacrifice—communities like Proctor and Andersonville surrendered for flood control and electricity generation, with residents forced to relocate and even move family graveyards, forever altering Appalachian cultural landscapes. Yale, Kentucky, once a bustling community established by Sterling Lumber Company, now lies beneath Cave Run Lake which was built primarily for flood control in the early 1970s. The residents of Proctor faced a particularly bitter outcome when the government built only 6 miles of the promised 30-mile road that would have provided access to their family cemeteries.

Alabama’s Submerged Communities

Beneath the tranquil waters of Alabama’s extensive reservoir system lie communities that once thrived with daily life, commerce, and cultural significance—now preserved only in historical records and the memories of displaced families.

When you boat across Smith Lake or Lake Martin today, you’re gliding over the remnants of forgotten towns. Easonville’s history ended when Alabama Power flooded the area in the 1960s, forcing approximately 60 families to relocate after their homes were burned and cemeteries exhumed. The town once featured three stores and multiple churches that created a warm, tight-knit community atmosphere.

The prosperous Kowaliga community, founded by freed slaves after the Civil War, disappeared beneath Lake Martin in 1926, erasing a crucial piece of Black heritage in Alabama. Local residents frequently share cautionary tales about the varying depths near submerged structures like the old railroad bed. Cahaba, once Alabama’s capital, succumbed to repeated flooding, while numerous Tennessee River settlements vanished under 1930s dam projects, their stories submerged but not forgotten.

Western Ghost Towns Beneath the Waves

The western United States harbors its own aquatic necropolises, where entire communities now rest in watery tombs beneath artificial lakes and reservoirs.

These submerged settlements reveal America’s complex relationship with water management and progress. Ghost town exploration becomes possible during severe droughts when these underwater time capsules temporarily resurface, offering glimpses into the past. Old Bluffton’s remains have been covered by Lake Buchanan since the Buchanan Dam construction in 1937. St. Thomas was completely flooded in 1938 when Lake Mead filled behind the Boulder Dam.

- Old Bluffton emerges from Lake Buchanan during Texas droughts, revealing tombstones and a cotton gin.

- St. Thomas’s foundations become visible when Lake Mead recedes, attracting underwater archaeology enthusiasts.

- Kennett lies 400 feet deep in Shasta Lake, its mining past entombed with polluted industrial remains.

- Proctor’s disappearance beneath Fontana Lake left family cemeteries accessible only by ferry.

- Whiskey Flats periodically reappears when its reservoir shrinks to critically low levels.

Natural Disasters and Lost Pacific Northwest Settlements

You’ll find the Pacific Northwest’s landscape haunted by settlements lost not only to dam construction but also to nature’s fury.

The Great Flood of 1862 completely obliterated towns like Champoeg and Linn City in Oregon, while coastal communities such as Bayocean suffered a decades-long death by erosion, eventually disappearing entirely by 1971. Once marketed as the “Atlantic City of the West”, Bayocean’s buildings gradually succumbed to the sea after jetty construction altered natural sand patterns. Similar to these natural disasters, the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam resulted in the flooding of eleven towns and severely impacted tribal fishing rights.

These catastrophic events reshaped both the physical geography and cultural heritage of the region, particularly for Indigenous communities whose ancestral fishing grounds vanished beneath rising waters.

Pacific Coast Erosion

Along the rugged Pacific Northwest coastline, numerous communities have succumbed to the relentless forces of coastal erosion and flooding, creating ghost towns that now exist only in historical records and fading memories.

Historical erosion impacts transformed places like Bayocean, Oregon from ambitious resort towns into submerged ruins, while North Cove earned the ominous nickname “Washaway Beach.”

You’ll find that human interventions—including dams and jetties—dramatically altered natural sediment flows, accelerating coastal destruction and overwhelming local coastal preservation strategies. This was precisely the case with Bayocean, where residents constructed a single jetty that ironically hastened erosion rather than preventing it.

- Bayocean’s complete disappearance by 1971 follows decades of erosion and catastrophic storms

- North Cove lost critical infrastructure including its Coast Guard station and post office

- The Shoalwater Bay Tribe received $25 million in 2023 for climate-driven relocation

- Man-made structures intended as solutions often worsened erosion elsewhere

- Economic limitations frequently prevented effective protective infrastructure development

Bayocean once boasted a thriving community with 2,000 residents by 1914 before its devastating decline began.

Columbia Basin Floods

Beneath today’s serene Columbia Basin landscape lies evidence of cataclysmic flooding that ranks among Earth’s most dramatic geological events.

You’re witnessing the aftermath of Ice Age Missoula Floods—when an ice dam repeatedly failed, releasing Lake Missoula’s contents at 400 million cubic feet per second across eastern Washington.

The geological evidence is unmistakable: scoured basalt bedrock, massive sediment deposits, and distinctive landforms like the Channeled Scablands.

This flooding history transformed the region’s topography, carving deep channels and temporarily creating lakes over 400 feet deep.

These forces didn’t spare human settlements either.

The 1948 Columbia River flood obliterated Vanport, Oregon, killing 32 and displacing 18,000.

This destruction spurred federal flood control infrastructure development, though countless stories of lost communities remain submerged beneath regulated waters.

Mining Heritage Underwater: America’s Industrial Past

America’s mining heritage lies preserved in watery tombs, where once-thriving industrial communities now rest beneath reservoir waters.

You’ll find copper smelting operations in Kennett, California and gold rush settlements like Roosevelt, Idaho completely submerged, their economic booms forever silenced by dam projects and environmental disasters.

These underwater industrial landscapes offer a unique archaeological record of America’s extractive past, with rail lines, mining equipment, and entire town infrastructures waiting to be examined through historical research rather than conventional exploration.

Mining Boomtowns Now Submerged

While the placid surfaces of America’s reservoirs reveal little of what lies beneath, numerous mining boomtowns rest silently underwater—casualties of 20th-century infrastructure development that prioritized water management over historical preservation.

These submerged communities represent America’s hidden heritage, from copper boomtowns like Kennett, now 400 feet beneath Lake Shasta, to the industrial settlements of New England’s flooded valleys.

- Kennett, California’s once-thriving copper smelter town disappeared in 1944, its industrial legacy preserved in watery stasis.

- The Enfield area towns saw systematic demolition before flooding, with immigrant “woodpeckers” dismantling the communities.

- Greenwater’s copper boom went bust quickly, leaving substantial stone buildings to later face partial submersion.

- Mining towns in Death Valley’s Emigrant Canyon District reflect the remote, harsh conditions of western mineral extraction.

- Submerged history reveals America’s complex relationship with natural resources and industrial progress.

Rail Towns Beneath Water

Sprawling beneath the tranquil surfaces of America’s largest reservoirs lies a network of once-thriving rail towns that served as essential arteries for the nation’s mining industry before their submersion in the mid-20th century.

You’ll find Kennett, California buried 400 feet underwater, where its copper smelter operations and railroad infrastructure now form an eerie underwater landscape.

In Appalachia, Proctor, North Carolina and Loyston, Tennessee represent casualties of TVA projects, their industrial foundations now subjects of underwater archaeology.

The desert town of St. Thomas, Nevada occasionally resurfaces during droughts, revealing the skeletal remains of its railroad past.

These submerged histories represent America’s pragmatic sacrifice of industrial communities for hydroelectric progress, with countless miles of track, train stations, and mining-related infrastructure creating accidental underwater museums of early 20th century American industrialism.

Indigenous Cultural Sites Lost to Dam Projects

Beneath the placid surfaces of America’s vast reservoir systems lies a tragic legacy of cultural erasure that few visitors comprehend.

Beneath engineered waters lies an untold story of Indigenous dispossession most Americans never learn.

When you gaze across these manufactured lakes, you’re looking at over 1.13 million acres of submerged Indigenous lands—an area larger than Rhode Island. This flooding represents an incalculable loss of cultural heritage and historical destruction, with 424 dams inundating tribal territories without meaningful consent.

- The Winnemem Wintu’s sacred Puberty Rock vanished beneath Shasta Dam’s rising waters

- Columbia River’s Celilo Falls—a centuries-old tribal fishery—disappeared completely

- San Carlos tribal burial grounds were covered with concrete rather than relocated

- Fort Berthold Reservation lost 350,000+ acres, displacing 80% of residents

- River bottomlands essential to traditional farming and cultural practices were prioritized for sacrifice

Preserving the Memory of Flooded Communities

Though their physical structures may be lost beneath rising waters, America’s flooded communities live on through deliberate preservation efforts that maintain their cultural memory and historical significance.

You’ll find historical markers standing sentinel at former town sites like Vanport, serving as tangible reminders of what once existed.

Cemetery preservation represents one of the most poignant aspects of this work. When waters threatened to claim ancestral burial grounds, many communities methodically relocated graves into pine boxes, maintaining the exact layout of original cemeteries.

Not all received this treatment—some family plots and slave graveyards remain submerged.

Communities honor their submerged heritage through oral history projects, museum collections, and annual commemorations, while descendants maintain family traditions through reunions near their ancestral homesites, ensuring these towns aren’t merely drowned—they’re remembered.

Exploring Sunken Towns When Water Levels Drop

While preservation efforts maintain the memory of America’s flooded towns, nature sometimes provides extraordinary opportunities for direct historical engagement. During drought periods, receding waters reveal the submerged heritage of places like St. Thomas, Nevada, where Lake Mead’s fluctuations periodically expose foundations, walls, and street patterns.

- Archaeological remains become temporarily accessible for historical documentation at Lake Texoma when drought exposes grave markers and building foundations.

- Ashokan Reservoir’s extreme low levels reveal lost Catskill communities’ stone walls and road networks.

- Lake Hartwell droughts expose the remnants of Andersonville’s structural footprints.

- Norris Lake occasionally reveals portions of Loyston’s industrial foundations.

- Time constraints exist for exploration as water levels eventually rise again, reclaiming these ghostly landscapes.

Environmental and Social Impacts of Reservoir Creation

The creation of massive reservoirs across America has exacted profound environmental and social tolls that extend far beyond the visible flooding of towns and landscapes.

You’re witnessing the consequences of massive ecological disruption: reservoirs trap sediments, disrupt nutrient flows, and emit substantial greenhouse gases—equivalent to Canada’s annual emissions. This environmental degradation fragments river ecosystems, decimates biodiversity, and deteriorates water quality through toxin release and algal blooms.

Equally devastating is the cultural displacement experienced by communities forced to relocate. When reservoirs submerge homes, farms, and archaeological sites, they erase tangible connections to heritage and traditional ways of life.

Climate change further compounds these issues, intensifying sedimentation, warming reservoir waters, and threatening the long-term viability of these artificial lakes that have permanently altered America’s natural and social landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Divers Legally Explore Submerged Towns?

Yes, you can legally explore submerged towns if you’ve obtained proper permits, adhere to diver regulations governing underwater exploration, and respect historical preservation laws that protect these submerged cultural sites.

Do Former Residents Receive Compensation When Towns Are Flooded?

In over 85% of dam projects, you’ll find former residents received financial compensation for properties, though resident disputes frequently centered on inadequate valuations that didn’t account for cultural losses or their freedom to choose relocation terms.

Are Any Flooded Towns Visible During Drought Conditions?

Yes, during droughts you’ll discover flooded history reemerging when reservoir levels drop. Towns like St. Thomas and Proctor offer temporary windows for underwater exploration as their foundations and artifacts resurface.

How Were Burial Sites Handled During Planned Flooding?

Like submerged memories resurfacing, your ancestors’ resting places were often relocated before floods. You’ll find burial site preservation varied widely—some cemeteries were meticulously moved, while others became underwater historical sites awaiting rediscovery during droughts.

Could Modern Technology Help Map Underwater Ghost Towns?

You can utilize sonar imaging, LiDAR, ROVs, and GIS to create detailed underwater mapping of ghost towns, despite challenges like sedimentation and water clarity that complicate these technological approaches.

References

- https://www.thewanderingappalachian.com/post/the-underwater-towns-of-appalachia

- https://kids.kiddle.co/List_of_flooded_towns_in_the_United_States

- https://www.geotab.com/ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_flooded_towns_in_the_United_States

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YT8a1HbiyNI

- https://www.neh.gov/article/atlas-drowned-towns

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/lists/americas-best-preserved-ghost-towns

- https://www.thewanderingappalachian.com/post/underwater-ghost-towns-of-appalachia

- https://wvtourism.com/did-you-know-there-is-an-underwater-ghost-town-in-west-virginia/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wM7jS4r4SDE